In a possible list of the major and most important reference points for studying the history of the arts in Sarzana, a prominent place could certainly be occupied by a work by historian Bonaventura de’ Rossi (Sarzana, 1666 - Genoa, 1741), the copious Collettanea di memorie e notizie storiche, a large collection that the author put together with the aim of tracing an in-depth history of Lunigiana and, in particular, of Sarzana, and which, despite its bulk and importance, never achieved the success it perhaps would have deserved: and that it was not a bolshy text of mere local erudition is shown by the fact that interest in the copious Collettanea, during the eighteenth century, went beyond the borders of Lunigiana. As proof of this, consider that for Ludovico Antonio Muratori (Vignola, 1672 - Modena, 1750), Bonaventura is “persona studsissima delle antichità della Lunigiana, e del Genovesato, siccome apparirà anche un giorno dalle Storie da lui composte,” and for Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (Firenze, 1712 - 1783) the Collettanea copiosissima represented an extremely significant source for the drafting of the Reports of some journeys made in different parts of Tuscany, as the author himself declared in his volume (from this entire first very voluminous Book [of the Collettanea copiosissima, nda], I have extracted from it the most important and sure News, which I will publish in its place, together with the description of the modern ruins of Luni).

The considerable importance of the Collettanea cop iosissima for the history of art in Lunigiana was recently emphasized by art historian Piero Donati in his contribution, La Collettanea copiosissima di Bonaventura Rossi come fonte per la storia delle arti a Sarzana, published in issue LXV (2018) of the Giornale storico della Lunigiana e del territorio lunense: an exceedingly interesting essay because, on the one hand, it underscores the relevance of the copious Collettanea for scholars, both in general terms and for certain specific topics (for example, Donati points out that the evidence contained in the Collettanea on antiquities hunting assiduously practiced between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries should be carefully screened by specialists and re-proposed to the attention of a wide audience), and on the other hand, it uses with value some of the news contained in Bonaventura de’ Rossi’s abundant collection in order to corroborate some very recent and remarkable discoveries. All of this, however, always keeping in mind that Bonaventura’s interest in works of art is exclusively historical (“that is, as tangible manifestations of the glory of Sarzana,” Donati explains): nevertheless, this consideration does not make the news that the reader can find in the copious Collectorium any less noteworthy. Another merit of Piero Donati is then that of having compiled the essay in the form of a “journey” through eighteenth-century Sarzana, following Bonaventura de’ Rossi’s text: the result is therefore a fresh and enjoyable read.

|

| Bonaventura de’ Rossi, Collettanea copiosissima di memorie, e notizie storiche, con gran tempo e fatica autenticamente desunte per me Bonaventura de’ Rossi di Sarzana (1789-1790; paper manuscript in 5 volumes in-quarto; Private collection) |

|

| The Cathedral of Sarzana. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Sarzana, the Town Hall in Piazza Matteotti |

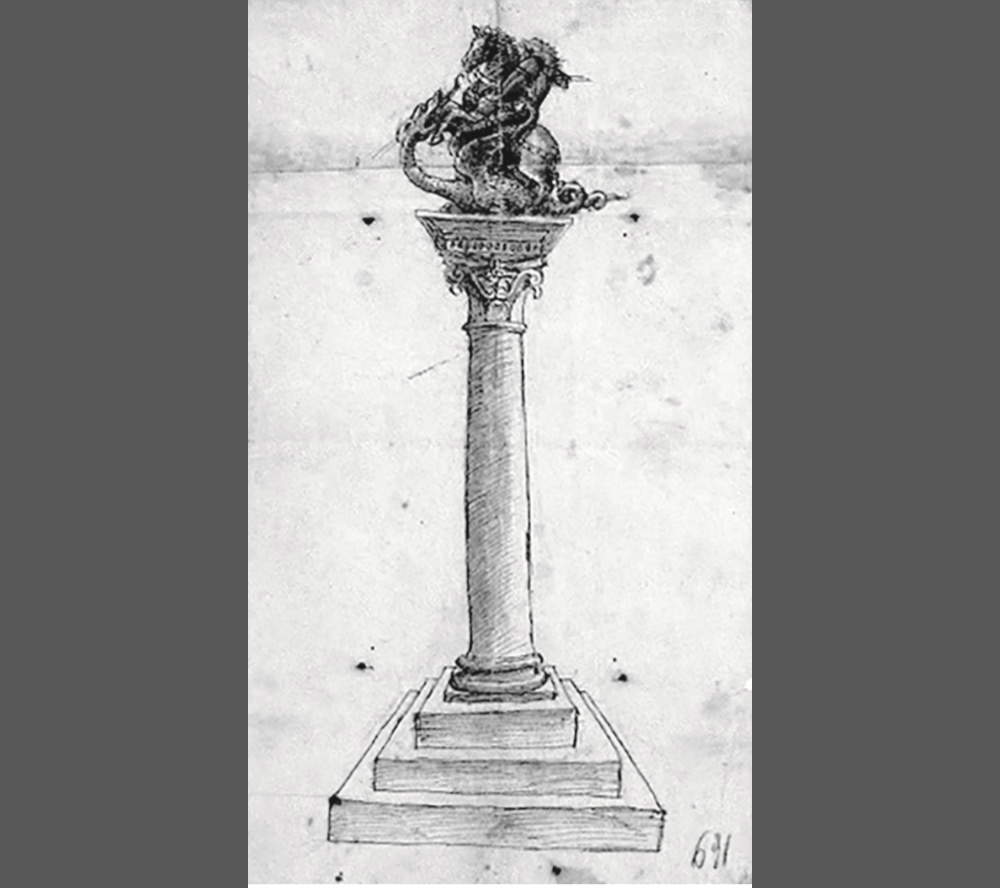

This journey begins from today’s Piazza Matteotti, the “Piazza del Comune” for the inhabitants, and formerly “Piazza della Calcandola” after the name of the small stream that flows through Sarzana. Bonaventura de’ Rossi attests that here once stood “a Marble Column with a statue of St. George on horseback [...] in the act of wounding the serpent”: Donati points out that it was “the most important among the representations of the emblem of the Banco di San Giorgio placed in Sarzana and in those villages of the Riviera di Levante that the Banco had administered on behalf of the Republic,” and was the work of one of the greatest sculptors of the Tuscan Renaissance outside Florence, Matteo Civitali (Lucca, 1436 - 1501), who executed the work in Carrara in 1499. The column was torn down in 1797, the year of the overthrow of the Genoese government led by Doge Giacomo Maria Brignole and the subsequent fall of the Republic of Genoa, an event following which the city of Sarzana passed to the newly established Ligurian Republic, at first an autonomous republic albeit closely dependent on the French, and then, from 1805, a territory directly incorporated into the First French Empire. The column, a loss of extreme gravity since it was a sculpture of great value and since it represented Civitali’s only work in the city, is now known only from a drawing penned by the hand of the Lucchese sculptor himself, and preserved in the Genoa State Archives.

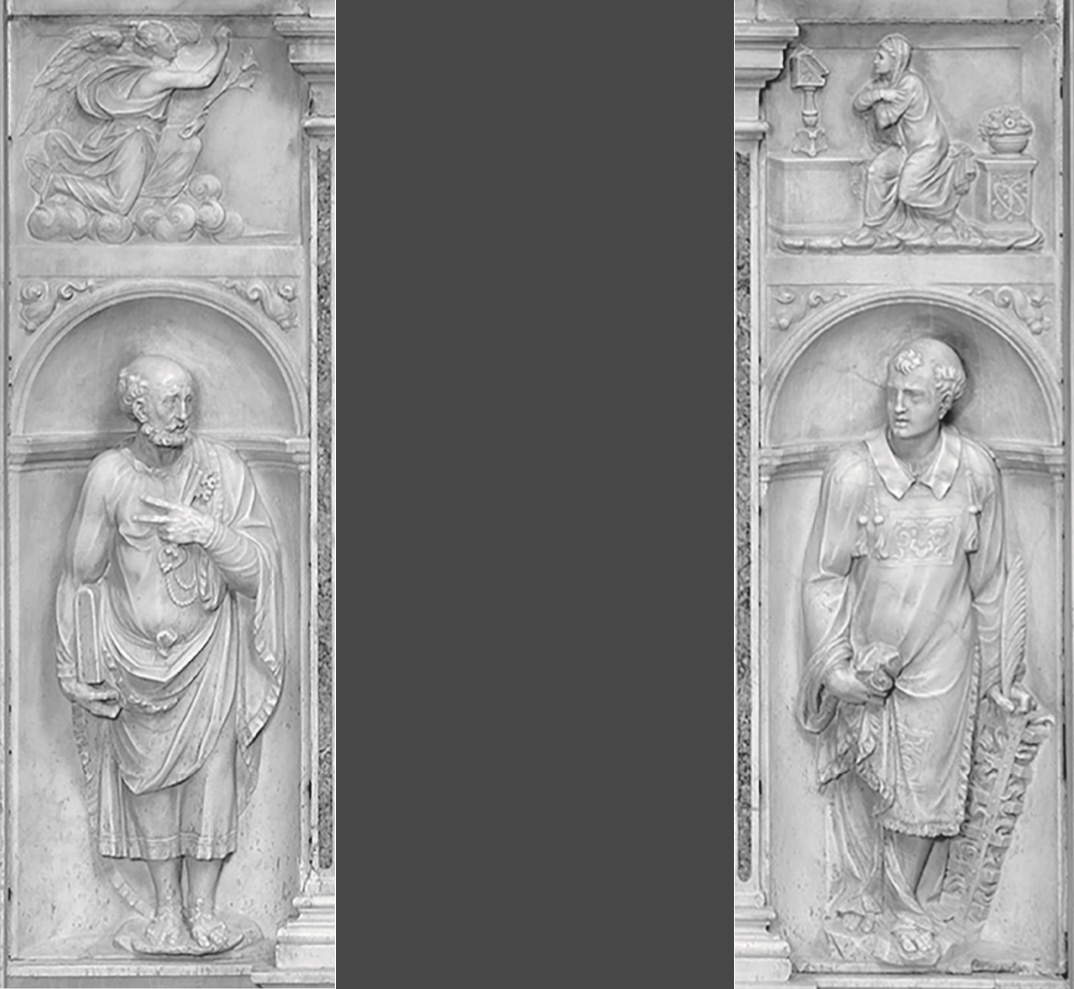

Continuing the itinerary, leaving the Piazza del Comune and entering the present-day Via Mazzini, the urban section of the Via Francigena and the main and busiest street in Sarzana’s historic center, after a short time we come to the parish church of Sant’Andrea, one of the oldest churches in the city: regarding the works contained in this house of worship, the information provided by Bonaventura de’ Rossi proved fundamental in reconstructing a convincing hypothesis on the authorship of what was once the marble altarpiece of the Altar grande of the pieve of Sant’Andrea. In particular, Bonaventura reports the existence of a “memorial” written by the workers of Sant’Andrea dated May 10, 1540, in which they mention the discovery of a crystal vase full of relics, during the course of the work of arranging the altar that preceded the creation of the marble altarpiece. The act was transcribed by the art historian Lorenzo Principi as part of his 2014 contribution, published in the scientific journal Nuovi studi, and concerning two unpublished sculptures by Silvio Cosini (Fiesole, late 15th century - Milan?, after 1549), depicting St. Peter and St. Lawrence, preserved at the church of San Lorenzo in Portovenere, and because of their typology related to two reliefs reported by Donati in 1999, kept in a private collection in Sarzana, and depicting St. Peter and St. Bartholomew.

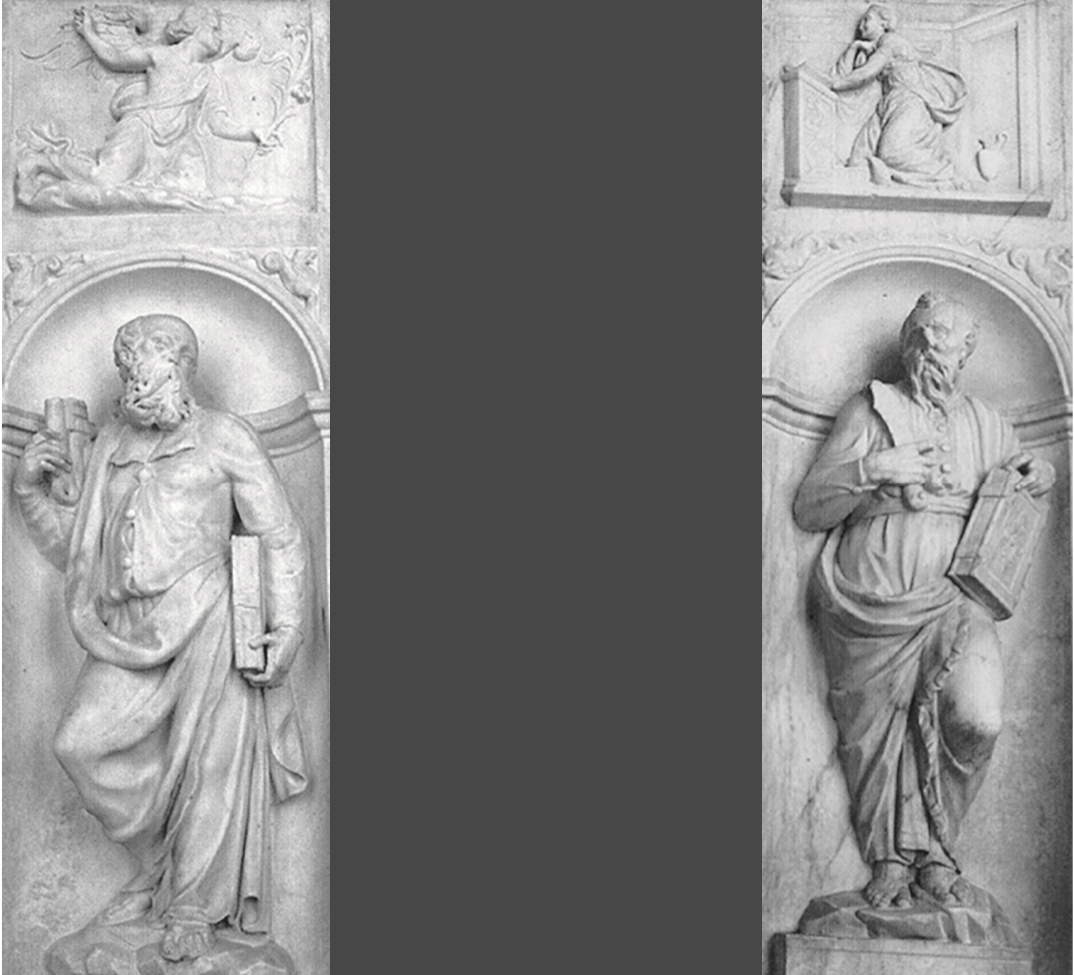

The two reliefs in the private collection, “characterized,” Donati specifies, “by a disruptive energy that stands at the antipodes with respect to the palpitating Cosinian language,” could be referred to a “personality of relevant caliber,” capable of updating himself on the outcomes of contemporary sculpture by Michelangelo (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564) and Baccio Bandinelli (Florence, 1488 - 1560): the artist, for Donati, may have been Prospero Sogari Spani (Reggio Emilia, 1516 - 1584), also known as Prospero Clemente or Clemente da Reggio, an Emilian artist who was among the major sculptors of the sixteenth century in his native lands, present several times in Carrara, and to whom can be referred two sculptures still present inside the parish church of Sant’Andrea (but once on the portal), depicting a St. Andrew and a St. Paul, the latter paired with a St. Peter, which, however, appears to be of a far inferior quality to be ascribed to the same author. The idea that the sculptor from Reggio Emilia may have been present in Sarzana in 1540, at the age of 24, to attend to the making of the statues of the marble ancon of St. Andrew, is certainly fascinating, not least because it would enrich Prospero Clemente’s catalog with two additional works of great quality, the saint Peter and the saint Bartholomew, placed in the context of the scheme of a triptych that nevertheless “does not prevent the personality of the sculptor from emerging,” Donati says: if in the bearded heads of the two saints, and in particular in that of St. Bartholomew, there appears for the first time a virile type to which Prospero will remain constantly faithful, the overbearing outstretching of the knees wrapped in the robe finds a timely counterpart in the female figures mourning the deceased in the Del Prato monument, while the stupendous hands of St. Bernard degli Uberti find a precedent in those of the aforementioned Bartholomew. The references are therefore two important known early masterpieces by Prospero, namely the funeral monument of Bartolomeo del Prato and the monument to Saint Bernard degli Uberti, both executed in 1543 and 1544, respectively, for Parma Cathedral.

|

| Matteo Civitali, Project for the column of San Giorgio di Sarzana (1499; Genoa, State Archives). Ph. Credit Archivio Piero Donati |

|

| Silvio Cosini, San Pietro and San Lorenzo (Portovenere, San Lorenzo). Ph. Credit Archivio Lorenzo Principi |

|

| Prospero Clemente, San Pietro and San Bartolomeo (Sarzana, Private collection). Ph. Credit Lorenzo Principi Archive |

|

| From left to right: Prospero Clemente, Saint Andrew; Prospero Clemente, Saint Paul; Unknown 16th-century sculptor, Saint Peter (Sarzana, Pieve di Sant’Andrea). Ph. Credit Archivio Piero Donati |

Continuing our walk through the center of Sarzana, we come, having traveled a few dozen meters, to the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, where one of the capital works of Italian art history is preserved, namely the so-called cross of Guglielmo: in the copious Collectorium we find rather interesting information, which enriches the history of this cornerstone of art. First, Bonaventure compares the physical features of the body of Jesus on the cross with those that emerge from the description of the so-called “Letter of Publius Lentulus,” an apocryphal New Testament text attributed to the Roman Publius Lentulus, governor of Judea before Pontius Pilate, who in his text allegedly drew up a report to be presented to the emperor Tiberius and in which the events of Jesus are abundantly discussed. Bonaventure’s remark could be eighteenth-century evidence in support of the thesis, on which all scholars today agree, that the aforementioned letter was actually composed in the medieval age. Moreover, again on the subject of William’s cross, Bonaventure quotes a “poet of our surroundings” who, in Latin verse, gave an account of how the crucifix was already in ancient times an object of profound veneration by the faithful, who came en masse (“populi concursus maximus”) to revere it.

Still, among the noteworthy statements, one concerns the ancient monastery of the Poor Clares, which occupied the area corresponding to today’s Piazza Garibaldi: in the lintel of the portal of the church attached to the convent, Bonaventura writes, “veggonsi li coats of arms of the Royal House of France, and of the House Malaspina, having by tradition that such a door was made with the alms of French Ministers, who kept Sarzana occupied for Charles VIII.” The reference is to the historical episode of the meeting between Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici and Charles VIII, held on October 31, 1494 in Santo Stefano di Magra: the lord of Florence decided to make a meeting with the king of France in order to avoid an unnecessary war, pandering to the wishes of Charles VIII who, in his march toward the Kingdom of Naples over whose crown he boasted hereditary rightsî, demanded free passage through Tuscany and the handing over of a number of strategic cities, among which was Sarzana itself, whose keys Piero de’ Medici handed over to Charles VIII during the meeting in Santo Stefano. Donati then notes the attention that Bonaventura de’ Rossi devoted, in his copious Collettanea, to stone materials: for several buildings, in fact, the historian indicated the composition of the construction materials and their origin, thus also providing various useful information regarding the sources of supply of the marbles and stones with which several monuments were built in and around the city.

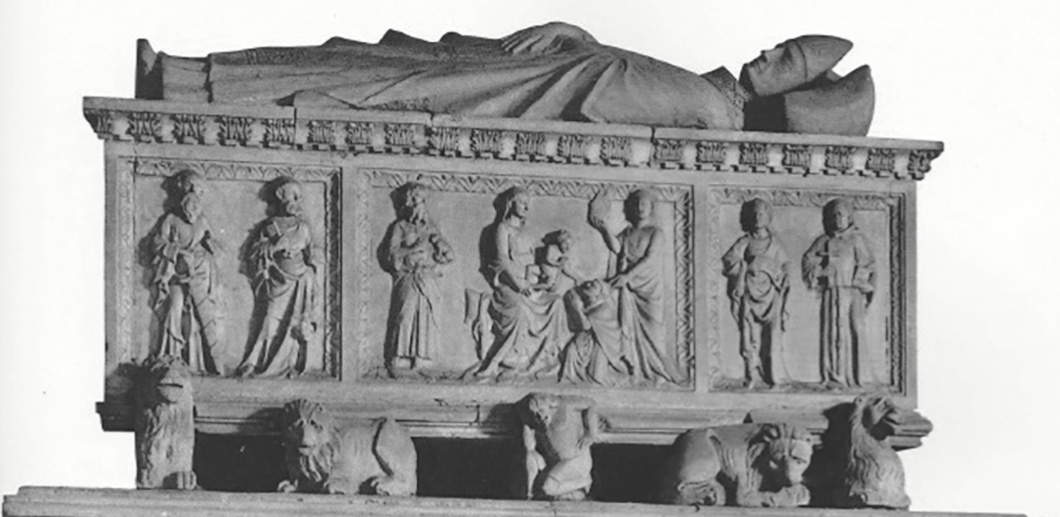

Finally, the notation regarding the funeral monument of Bishop Bernabò Malaspina (1274 - 1338), made by a fourteenth-century French sculptor working in the area and preserved at the church of San Francesco, of which Bonaventura recounts in some detail certain vicissitudes it encountered, also “in keeping with the pro-Malaspina setting of his work,” as Donati asserts, deserves mention. According to Bonaventura’s account, “it was this ancient deposit of noble, et eccellente struttura secondo luso di quei tempi, ellevato con colonne, et altri ornamenti di Marmo, che dal Capriccio di un Guardiano di questo Convento non senza grave dispiacere, e sdegno de Marchesi di Fosdinovo furono levate via in gran parte e vendute le Colonne alla Compagnia di S. Croce to support the orchestra vault of the organ of that oratory, which therefore nebbe the Convent de Frati for the course of many years sensible pregiudizii for lack dellelemosine de Marchesi, et abitanti dello Stato di Fosdinovo.” Put another way, the monument of Bernabò Malaspina was disassembled from its original location (the Sarzano historian, however, does not specify the year of the event) to be reassembled in another place and in a reduced form (and of the columns reused in Santa Croce, moreover, there is no further news). Interestingly, a restoration carried out in 2004 confirmed the goodness of Bonaventura’s claim: not only that, the figure of the bishop, for several years, seems to have been left to the elements. For these reasons, the Malaspina marquises of Fosdinovo suspended the donations sent to the church.

|

| Guillielmus (William), Christus Triumphans (1138; tempera on panel, 299 x 214 cm; Sarzana, Cathedral) |

|

| French sculptor, Commendatio animae of Bishop Bernabò Malaspina, detail of the bishop’s tomb (Sarzana, San Francesco). Ph. Credit Archivio Piero Donati. |

Those mentioned so far are but a few of the examples Donati derived from his analysis of Bonaventure’s text: a rich source of information, a valuable collection of historical annotations on many facts about Sarzana and Historical Lunigiana, Bonaventura de’ Rossi’s copious Collettanea is certainly not one of the easiest historical texts (and perhaps its misfortune is also due to this fact), but its inescapable importance for the study of the events of Sarzana and Lunigiana in the past is undeniable, and the merit of Piero Donati’s essay is precisely that of having emphasized the considerable value of such a collection, which must certainly be assigned considerable weight in the sphere of studies on the art of this area of Liguria, filled with masterpieces of rare merit.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.