Among the cantos of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy , the fifth ofInferno, in which the story of Paolo and Francesca is told, is one of the most famous. After encountering Minos, a monster and infernal judge who twists his tail around his body as many times as the circle into which the damned in front of him must descend, Dante and Virgil arrive in the second circle of hell: here they are swept by a violent storm, with contrary winds that cross dragging the souls of the damned before a precipice, and each time those damned souls scream, cry, blaspheme. They are the lustful, “carnal sinners / who reason add up to talent,” forced to be dragged violently by the winds as in their lives they were dragged by instinct instead of reason. All died violent deaths by their own hand or by the hand of others because of the love they could not resist during their existence. Famous characters from history and myths can be recognized among the souls, such as Semiramis, Dido, Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, but in particular Dante is attracted to two souls who move next to each other, reading, and therefore he asks Virgil if he can turn to them so that they can tell him their story: they are Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta. A tragic love story made famous by some of the best-known verses in Italian literature: “Amor, ch’al cor gentil ratto s’apprende, / prese costui de la bella persona / che mi fu tolta; e ’l modo ancora m’offende. / Amor, ch’a nullo amato amar perdona, / mi preso del costui piacer così forte, che, come vedi, ancora non m’abbandona. / Amor condusse noi ad una morte. / Caina attende chi a vita ci spensensens.” It is Francesca who speaks and tells that their death was caused by the love they felt for each other, even though both were already bound by another bond of love: she to Gianciotto, Paolo’s brother, and he to his wife. Love does not forgive anyone to love someone who is already loved by another person, even more so if the two lovers are brothers-in-law.

Dante, even more eager to learn about their affair, asks Francesca how Love granted them knowledge of desire and passion, and as Paolo wept, she confides that galeotto was the book that told of Lancelot’s forbidden love for Guinevere (King Arthur’s wife) and that when they got to the point of the kiss between the two, Paolo kissed her on the mouth. Discovering them, however, was Gianciotto, who pierced both of them with a sword. For this they are condemned to be dragged by furious winds into the second circle of Hell, but in spite of this they continue to love each other and stand by each other’s side.

That of Paolo and Francesca is one of the most celebrated loves of all time, not only in literature, but also in art. In thenineteenth century in particular, many artists in Italy and abroad, driven by an interest in representing themes related to literature and the classics, transposed the story of the two lovers on their canvases, in the various moments of the tale. Essentially three: the intimate meeting of the reading with the subsequent kiss, the discovery of betrayal by Gianciotto and the killing of the lovers, and finally Paolo and Francesca in the Inferno.

Through some artistic masterpieces, it is possible to retrace the various episodes of the narrative.

The German painter Anselm Feuerbach (Speyer, 1829 - Venice, 1880) very often dealt with themes from Italian literature, and in a painting from 1864, now in the Schack Collection in Munich, he depicted Paolo and Francesca intent on reading the story of Lancelot, as recounted in Canto V of Dante’s Inferno: “We read one day for delight / of Lancialotto as amor gripped him; / alone we were and without any suspicion.” In a scene that is still very chaste, although the approach on the part of the young man toward the maiden both with his face and with his arm resting on the back of the seat hints at something, the two are immersed in an almost bucolic setting, among the vegetation; she has the book in her hands and holds the mark of the pages with her fingers, but no amorous desire is yet apparent, especially on her part. It is an intimate and collected scene, but without abandonment to feelings.

“When we read the disheveled laughter / being bashed by such a lover, / these, who never from me shall not be divided, / my mouth bashed all trembling.” The surrender to amorous desire with the kiss on the mouth between the two young men is depicted by Amos Cassioli (Asciano, 1832 - Florence, 1891): compared to Feuerbach’s painting, the setting also changes, as in an indoor, domestic setting, where wooden furniture predominates. The two brothers-in-law are seated next to each other; Francesca is taken aback by the passionate kiss Paolo gives her on the lips, brushing her chin with his fingers. That everything happened suddenly can be sensed from the girl’s posture, who remained petrified with her arms stretched over her skirt, and especially from the book dropped half-open on the floor. An intimate and passionate scene.

|

| Anselm Feuerbach, Paolo and Francesca (1864; oil on canvas, 137 x 99.5 cm; Munich, Sammlung Schack) |

|

| Amos Cassioli, Paolo and Francesca (1870; oil on panel, 21 x 31 cm; private collection) |

Set on a terrace from which the surrounding landscape can be seen, on the other hand, is the painting by the Scotsman William Dyce (Aberdeen, 1806 - London, 1864). What is depicted in the work housed in the National Galleries of Scotland is a scene of courtly love: there is a feeling, but depicted with absolute composure; the kiss is not given on the mouth, but on the cheek, and the maiden shyly turns her face away. Nor is there the same impetus as in Cassioli’s painting, as the book remains firmly on her lap. The musical instrument leaning against the low wall and the presence of the moon also hint at a courtly scene. A hand can be glimpsed on the left: it is that of Gianciotto who surprised the lovers; in fact, the painter had originally included his figure as well.

The Victorian painter Sir Frank Dicksee (London, 1853 - 1928) depicted in one of his 1894 works the moment after the kiss between the two brothers-in-law: this is understood from the fact that the book with the story of Lancelot has already fallen on the floor of a rather luxurious room. Francesca rests her head on Paolo’s shoulder, who pulls her close to him and tenderly kisses her hand. In the scene, characterized by a certain richness in both furnishings and clothing, there seems to hover a sense of guilt, a restlessness of soul that, although the two do not yet know it, presages their tragic death.

As the Pre-Raphaelite that he was, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (London, 1828 - Birchington on Sea, 1882) was fascinated by literature and conceived of his art as having a similar quality to the literary works of his favorite writers, particularly Dante Alighieri: the artist translated the works of the Supreme Poet, and his father was also a Dante scholar (so much so that he named his son after his favorite writer). Among his works centered ontragic and romantic love, Dante Gabriel Rossetti created in 1855 a painting divided into three parts, now housed in London’s Tate Britain, which depicts the illicit love between Paolo and Francesca: the earthly kiss of the two lovers, Dante and Virgil shaking hands, and the hellish embrace between the two young people.

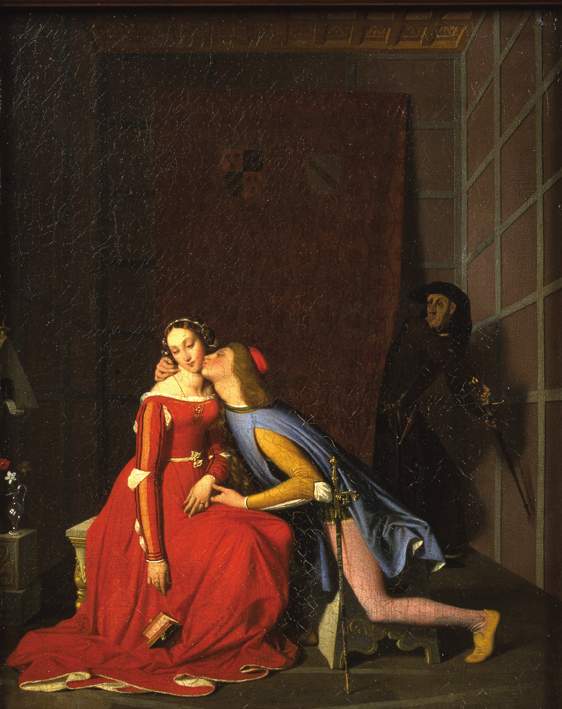

The moment when Gianciotto discovers the betrayal is well depicted by the French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Montauban, 1780 - Paris, 1867) in at least seven versions, very similar to each other, but whose most complete version is considered to be the one preserved at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Angers. In a composition reminiscent of the Northern Renaissance, Paolo and Francesca are in a narrow room, accessed through a door covered by a thick curtain. The young man reaches out in an almost diagonal pose toward the face of the beautiful Francesca and gives her a kiss on the cheek; the latter blushes as the small book falls from her hands. From behind the curtain, however, Gianciotto is already ready to draw his sword to perform his tragic deed.

|

| William Dyce, Francesca da Rimini (1837; oil on canvas, 142 x 176 cm; Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland) |

|

| Frank Dicksee, Paolo and Francesca (1894; oil on canvas, 130 x 130 cm; private collection) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1855; watercolor on paper, 25.4 x 44.9 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Paolo and Francesca (1819; oil on canvas, 50 x 41 cm; Angers, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

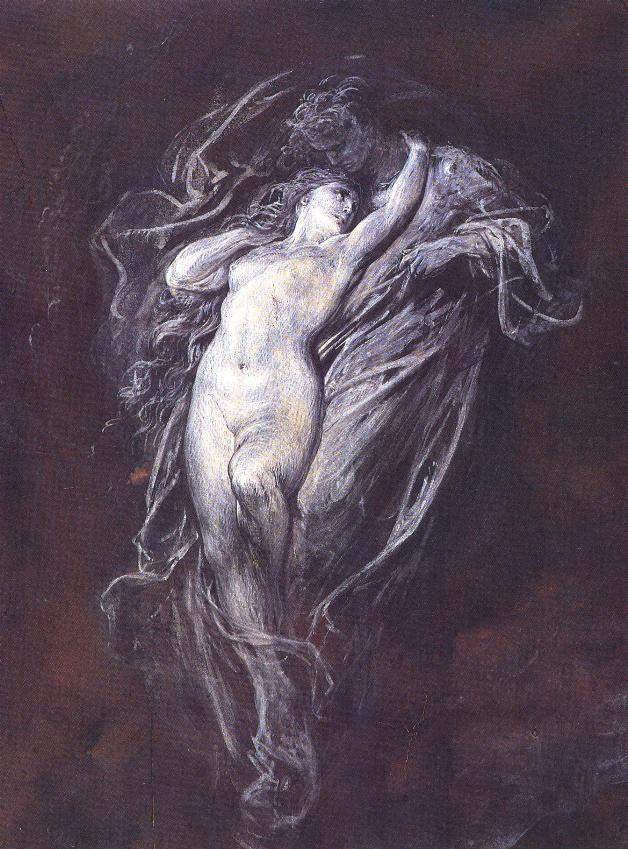

Gustave Dorè (Strasbourg, 1832 - Paris, 1883), a painter and engraver, illustrated theInferno of the Divine Comedy in 1861, and among the most evocative and almost dreamlike images he accomplished is his depiction of the two souls of Paolo and Francesca being drawn “like doves by desire called / with wings lifted and firm to the sweet nest / vegnon per l’aere, dal voler portate.” Francesca’s naked and sensual body clings to the figure of Paolo who stands behind her and looks at her in protection. The two complement each other in a single figure, emphasizing the deep and strong love by which they are mutually bound.

In an extremely evocative vision, Gaetano Previati (Ferrara, 1852 - Lavagna, 1920) depicted in 1909 in a painting presented at the Venice Biennale and now preserved in Ferrara, at the Gallerie d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, the torment of souls in the circle of the lustful, among which those of Paolo and Francesca are seen embraced. An intertwining of forms ascending in a whirlwind rendered with undulating brushstrokes and shaded strokes. A scene that fully denotes the artist’s own Symbolist and Decadentist vein.

The naked and embracing bodies of the two lovers wrapped in a drape are the protagonists of the work by the Dutch artist naturalized French Ary Scheffer (Dordrecht,1795 - Argenteuil, 1858): theirs is an almost theatrical pose, particularly that of Paul who, with his mouth half-open and eyes closed, raises his arm bringing his hand to his forehead in a gesture of despair. The two, illuminated by a strong light, are contrasted with the figures of Dante and Virgil in the darkness: the latter are curiously observing the souls of the two doomed lovers.

“Mentre che l’uno spirto questo disse, / l’altro piangëa; sì che di pietade / io venni men così com’io morisse. / E caddi come corpo morto cade.” Just as happens in the scene of the painting by Nicola Monti (Pistoia 1780 - Cortona 1864), the artist’s first documented work completed in 1810 for Livorno shopkeeper Luigi Fauquet, his main patron. Entering the Uffizi collections last year on the occasion of the Dantedì, the work refers back to the end of Canto V of Dante’sInferno, when the tragic tale of Paolo and Francesca fills the Supreme Poet’s heart with so much compassion that he is knocked unconscious and falls to the ground as if dead, next to Virgil.

|

| Gustave Doré, Paolo and Francesca in Hell (1861; ink and white gouache on paper, 38.7 �? 29.2 cm; Strasbourg, Musée dArt Moderne et Contemporain) |

|

| Gaetano Previati, Paolo and Francesca (1909; oil on canvas, 230 �? 260 cm; Ferrara, Gallerie d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Ary Scheffer, Francesca da Rimini (1835; oil on canvas, 166.5 x 234 cm; London, Wallace Collection) |

|

| Nicola Monti, Francesca da Rimini in Dante’s Inferno (1810; oil on canvas, 168 x 21 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.