Over the course of a long life (he died at age 87) and a very long cardinalate (he wore the purple for 55 years, beginning in 1645), Cardinal Alderano Cybo (Genoa, 1613 - Rome, 1700) translated a great interest in the arts - from music to literature, from figurative arts to architecture - into assiduous patronage: he protected artists, promoted the construction of altars and chapels, commissioned statues and especially canvases, either to be destined for churches that were benefited by his munificence or to be included in his own chosen picture gallery. To the greater glory of God, of course, but also to the glory and imperishable memory of himself, and in honor of his own most illustrious family, those Cybo Malaspina who, ruling over one of the smallest states into which the Peninsula was then divided, the duchy of Massa and principality of Carrara, could boast the prestigious status of sovereign princes.

The cardinal wanted to embellish the churches of the cities of which he was bishop (Jesi, Ostia, Velletri) and especially the temples of his hometown, Massa, to which for decades he sent paintings, sculptures, objets d’art, and architectural designs, contributing in a decisive way to reorient in the direction of Rome the local taste, which until then had been subject to the influence of the two equidistant poles of Genoa and Florence. It was in the Eternal City, however, that the prelate’s patronage left its most magniloquent fruit: the rebuilt family chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, one of the most significant testimonies to late Roman Baroque. The pageantry of which sounds like a polemical response to the climate of neo-Tridentine austerity promoted, in the years in which the chapel was erected, by Pope Innocent XI (whose Secretary of State Alderano was also).

Great attentions were reserved by Cardinal Alderano Cybo for the church of San Francesco in Massa, in which, between the early 1660s and the mid-1680s, he promoted the construction of thehigh altar and the two transept altars: grandiose ’machines’ in which polychrome marbles (jasper for the high altar, Rosso di Francia for the other two) are combined with Apuan white. Despite alterations over time, this sumptuous triad can still be admired in the Massese church, which has since become the town’s cathedral. The canvases that the cardinal commissioned for the transept altars can now be seen on two altars in the nave: these are altarpieces that the prelate ordered from one of his trusted artists, the Roman painter Luigi Garzi (Rome, 1638 - 1721), who depicted in one canvas The Trinity worshipped by Saints John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, Peter and Andrew, and in the other (surely among Garzi’s most successful works) theImmaculate Conception, with another quartet of saints (Augustine, Ambrose, Athanasius and Jerome) exalting its purity. The painter worked extensively for Cybo: in addition to being employed, as we shall see, in the Cybo Chapel, Garzi painted in 1687 a luminous altarpiece depicting the Madonna and Child and Saints for the Oratorian church of San Giovanni Battista in Jesi, whosealtar maggiore (a majestic altar in polychrome marble, also the result of a Cybean commission), while a few years later, in 1693, he made a large oval with a dramatic Martyrdom of Saint Aurea for the cathedral of Ostia.

The other Massese church that benefited greatly from the cardinal’s munificence was the collegiate church of San Pietro. The city’s main temple had a troubled history: it almost completely collapsed in 1671, after which it was decided to erect a new and more grandiose church on a site not far away, then the undertaking was abandoned and the reconstruction of the ancient collegiate church was opted for, which, with the decisive financial support of Cardinal Alderano, was completed in 1701. The renovated building survived only a little more than a century: in 1807 Elisa Baciocchi, Napoleon’s sister, decreed its demolition, so that a large square would open in front of the Ducal Palace of Massa, which was then known, by virtue of the double row of trees surrounding it on three sides, as Piazza degli Aranci. Cardinal Cybo contributed to the reconstruction of the collegiate church, as well as financially, by sending from Rome the project for the grandiose twin altars of the transept, designed by the Lucchese architect, Roman by training, Domenico Martinelli, and by commissioning Giovanni Lazzoni, assisted by his sons Andrea and Tommaso, to create a monumental marble high relief depicting the Madonna of the Rosary, executed on the basis of a model by a Roman artist, sent to Massa by Alderano.

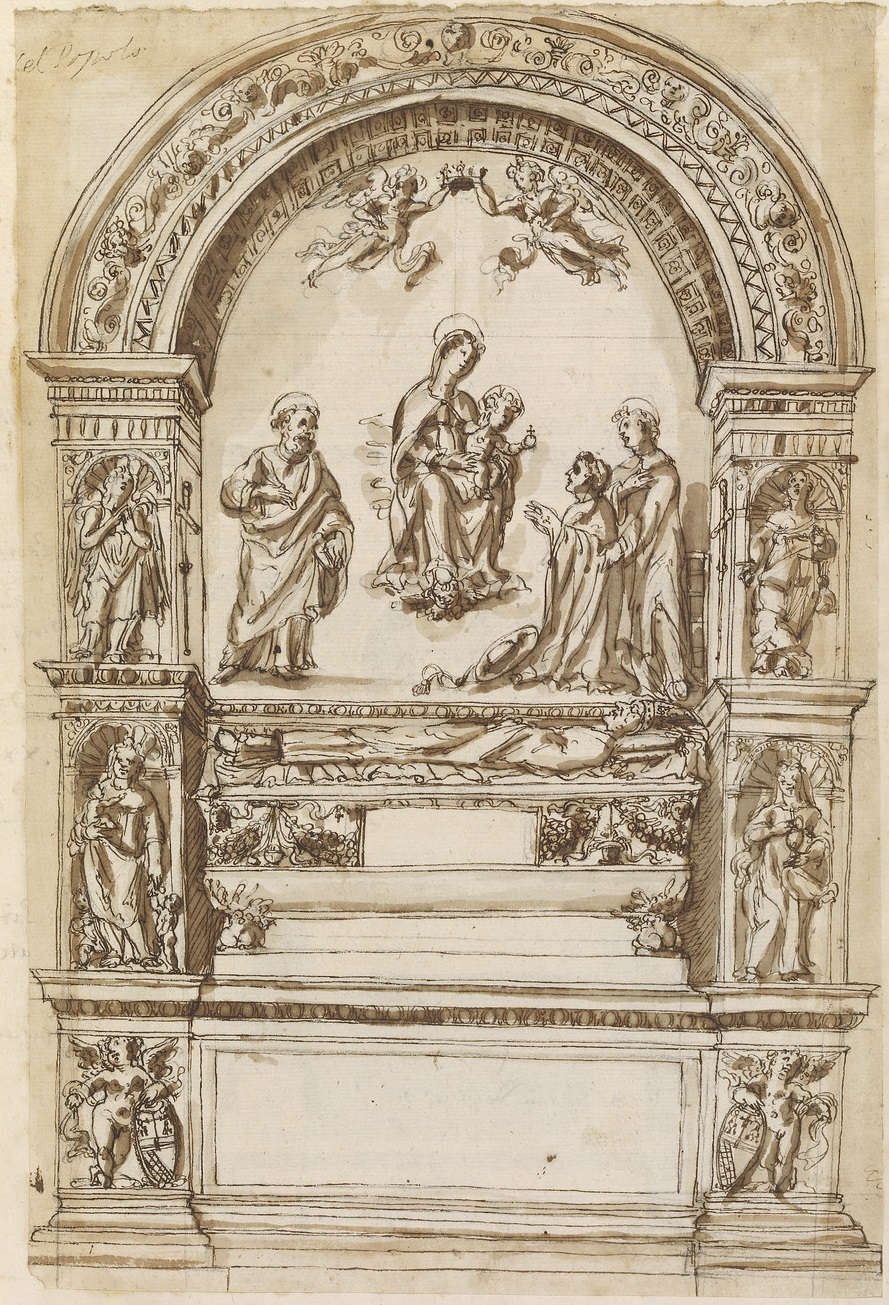

It was probably after Sept. 21, 1676, when Cardinal Benedetto Odescalchi was elected pope with the name Innocent XI, that the ambitious Cardinal Alderano, seeing the possibility of being elected to the throne of Peter and thus being able to benefit from a papal tomb in St. Peter’s basilica fading away, began to think of the family chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo as the place of his own burial, and of an intervention to radically transform the sacellum. The chapel of which the Cybo family held the jus patronage was the second on the right as one entered the church and had been built by Cardinal Lorenzo De Mari Cybo, nephew of Pope Innocent VIII, in the very early years of the sixteenth century. Alderano first turned to the elderly Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) for the design of the new chapel, only to fall back on his best collaborator, Carlo Fontana (Rancate, 1638 - Rome, 1714), when the latter died in 1680. The architect designed a space with a Greek-cross plan and domed roof, preceded by a rectangular vestibule and enlivened by the presence of as many as eight pairs of free-standing twin columns. The interior would feature a very rich covering of polychrome marble; the sixteen columns would be made of jasper from Sicily.

Work began in early 1682 and was completed five years later, in 1687. The cardinal and Fontana did not shy away from the challenge posed by the chapel that stood exactly opposite that of the Cybo family, Raphael’s celebrated Chigi Chapel. The strategy was to emulate, through a series of formal revivals and allusions, the Chigi and to surpass it in the richness of the marble facing and monumentality of the whole. Already the overall structure of the new building hints at Raphael’s work, not only because of its character as a small ’church within a church’ surmounted by a dome, but because of the arrangement of the coupled columns, which tends to reproduce that effect of a cross with rounded corners observable in the Chigi Chapel. Then there is the altar, whose simple and elegant form is exemplified by that of the Chigi altar. The altars of the two chapels, both dedicated to the Virgin, accommodate altarpieces with similar subjects: the Birth of the Virgin by Sebastiano del Piombo corresponds, on the altar of the cybea chapel, to the Dispute of the Immaculate Conception by Carlo Maratta (Camerano, 1625 - Rome, 1713), which also in the technique used (oil on wall) recalls Sebastiano’s work, painted in oil on a peperino-lined wall.

The emulation of Raphael is also a central theme in the Disputa marattesca, a masterpiece of crystalline composure in which, celebrating the purity of Mary’s conception, depicted at the top of the altarpiece, are gathered Saints John the Evangelist, Gregory the Great, Augustine and a Doctor of the Eastern Church, in whom Athanasius should probably be recognized. Reference to the Urbinate is of course constant in the production of an artist such as Maratta: we are, however, dealing with something that goes far beyond an obvious Raphaelesque influence. The space in which the scene is set is the same stage on which the much larger company of saints that populates the Dispute of the Blessed Sacrament in the Stanza della Segnatura is gathered. It is clear how such a, palpable reprise of the Vatican Disputa is not only about the aesthetic dimension, but also has resounding theological implications: Mary’s immaculate conception is equated with the fundamental dogmas of Catholicism, with that centrality of the Son and his sacrifice for human redemption, evoked in the sacrament of the Eucharist, which is celebrated in the Vatican Disputa , the theological fresco par excellence. Cardinal Cybo’s call, through Maratta, for a speedy definition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception (which would not occur until much later, in 1854) could not be expressed in more eloquent terms.

The execution of thefresco in the dome of the chapel was entrusted to Luigi Garzi. The painter shows us God the Father surrounded by a crowd of angels, prophets and Virtues arranged on heavenly clouds, at the moment when he grants Mary, depicted in the altarpiece below, the extraordinary privilege of her immaculate conception. Completing the chapel’s pictorial decoration are the two paintings facing each other in the entrance vestibule, depicting the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence and the Martyrdom of St. Catherine. The Austrian painter Daniel Seiter (Vienna, 1649 - Rome, 1705) created two oil-on-wall works that met with considerable success, but which, unlike Maratta’s altarpiece, executed with the same technique, met with rapid deterioration, so much so that Cybo was forced to replace them, in 1697, with two canvases, also painted by Seiter who, by then having moved to Turin, sent them from there to Rome. In their drama, Seiter’s canvases provide an appropriate counterbalance to the limpid impassivity of Maratta’sImmaculata .

When the first Cybo Chapel at the Popolo was demolished to make way for the second, not everything was destroyed. In particular, the funeral monument of the chapel’s founder, Cardinal Lorenzo, was donated by Alderano, in 1685, to the minor tertiaries of the convent of San Cosimato, in Trastevere, and reused as an altar. Of Pinturicchio ’s frescoes that adorned the sacellum, a portion was saved, depicting the Madonna and Child, which in 1687 Cardinal Alderano sent to his brother Alberico II, duke of Massa, so that the latter would place it on the altar of the ducal family’s new burial chapel, the construction of which had recently been undertaken in the Massese church of San Francesco (the present cathedral of the Apuan town). In October 1693 the fresco fragment was placed on the Ducal Chapel’s sumptuous polychrome marble altar, designed by Domenico Martinelli. Pinturicchio’s Madonna thus assumed a role as a dynastic relic and as a connecting element between the two Cybo chapels: it served as a reminder, in the place of the celebration of the Cybo Malaspina as sovereign princes, of the glories grasped by members of the lineage in Rome, in the service of the Church. To immortalize the prestigious Roman origin of the altarpiece, it was endowed with a glory of little angels in white marble among alabaster clouds, sculpted by the Carraresi Andrea and Tommaso Lazzoni: the lively cherubs do not merely hold the sacred image, but seem to carry it, as in the iconography of the translation of the Holy House of Loreto. Similarly, in the painting’s domed roofing, covered in ancient green romanissimo, one can perhaps discern an allusion to the chapel from which the fresco fragment came. Remarkably, finally, the Massese chapel was dedicated to the Nativity of the Virgin “ad immitazione,” as we read in a letter of the time, from the cardinal, who had dedicated his own renovated shrine to the Immaculate Conception.

In the same way that Pinturicchio’s frescoed fragment alludes in Massa’s family chapel to the Roman splendor of the lineage, the Cybo al Popolo Chapel makes clear the sovereign princely status of the Cybo Malaspina family. Cardinal Alderano had placed on the entrance arch to the chapel not his own cardinal’s coat of arms surmounted by the galero (which we also find in the center of the marble clad floor), but the coat of arms of the House, complete with a Malaspina flowering thornbush, surmounted by the ducal crown. The ’secular’ coat of arms dialogues with a coat of arms of Pope Innocent VIII, which is located a short distance away, in the keystone of the nave bay overlooked by the chapel: the dual glory of the family, civil and ecclesiastical, princely and papal, is visualized very directly through the juxtaposition of these two coats of arms.

To complete this overview of Cardinal Cybo’s activity as a patron, it remains to say a few words about his rich collection of paintings. The prelate began gathering it from the early 1950s, when, first as papal legate in Ferrara and then as bishop of Jesi, he acquired many works from the 16th-century Ferrarese school of painting and commissioned several paintings from Guercino. Once settled in Rome, the cardinal enlarged his collection, with works by a number of authors, including Giovanni Maria Morandi, Luigi Garzi, and Carlo Maratta: the latter, during the same period in which he executed the altarpiece for the chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo for the cardinal, painted for him a solemn Death of the Virgin, now owned by Torlonia and preserved at Villa Albani, and portrayed him in a splendid portrait, now at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseille.

When Alderano died, his paintings and books were transported to Massa and went to embellish the rooms of the Ducal Palace, where, however, they remained, for good measure, only a couple of decades: the last duke Cybo Malaspina of Massa, the great-grandson of the cardinal, who also bore the name Alderano, initiated the dispersion of the ducal collections, whose most valuable pieces can be traced in the major museums of Italy and Europe. Only one piece remains in Massa that can be traced back to the cardinal’s art collections: not a painting, but a bronze crucifix of sublime workmanship, the twin of those with the dead Christ that were made, based on models by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Ercole Ferrata, for St. Peter’s Basilica. Having escaped dispersal, the bronze is now in the Museo Diocesano in the Apuan town, a precious testimony to a season when reverberations of the artistic splendor of seventeenth-century Rome reached as far below the Apuan Alps.

The author of this article: Fabrizio Federici

Fabrizio Federici ha compiuto studi di storia dell’arte all’Università di Pisa e alla Scuola Normale Superiore. I suoi interessi comprendono temi di storia sociale dell’arte (mecenatismo, collezionismo), l’arte a Roma e in Toscana nel XVII secolo, la storia dell’erudizione e dell’antiquaria, la fortuna del Medioevo, l’antico e i luoghi dell’archeologia nella società contemporanea. È autore, con J. Garms, del volume "Tombs of illustrious italians at Rome". L’album di disegni RCIN 970334 della Royal Library di Windsor (“Bollettino d’Arte”, volume speciale), Firenze, Olschki 2010. Dal 2008 al 2012 è stato coordinatore del progetto “Osservatorio Mostre e Musei” della Scuola Normale e dal 2016 al 2018 borsista post-doc presso la Bibliotheca Hertziana, Roma. È inoltre amministratore della pagina Mo(n)stre.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.