Why is it that the Central Institute for Restoration, which since 1941 of its inauguration has been an undisputed point of reference in the entire world about conservation and restoration, in Italy has had to conduct its research work in the substantial indifference of the Protection Administration and the University, until it has been reduced to the zero in which it finds itself today? A question with many answers. One is in a distant affair. The very violent controversy opened by Roberto Longhi in 1948 against Brandi and the Icr with the Bergamo restorer Mauro Pellicioli at his side, who in the guise of the plaintive prealpine Iago suggested to him the technical targets against which to hurl himself.

Longhi, who was among the supporters of Icr’s founding in 1939 and who until the early postwar period would be a member of Icr’s technical council. Pellicioli, who at the very moment of Icr’s founding, by grace of his very close relationship with the Piedmontese art historian had been immediately appointed its chief restorer. A polemic against the Icr, in which Longhi put on the scales his undisputed authority as a great scholar and arbiter of the university careers of Italian art historians, to try to shut down the Icr or at least have its director, namely Brandi, dismissed. Controversy that the Piedmontese art historian opens in the “Corriere d’informazione” of January 5-6, 1948 with an article to which a few days later the Sienese art historian gives a straight answer. And if even today the reasons and boundaries of that affair are still not well understood, it can nevertheless be said with certainty that it was of the saddest cultural, technical and human level, up to and including the “letter of delatoria” (Antonio Paolucci writes it) that Longhi, seeing the failure to grasp the persecutory results he had pursued, sent on August 25, 1948 to the then director general Guglielmo de Angelis D’Ossat, claiming (again with Pellicioli blowing on the fire) that the Icr had ruined with wrong restorations some important paintings. How it was not true and how Brandi has easy game to prove.

A controversy that Urbani witnessed firsthand and that was formative for him (so he told me) about the violence and the moral and human paucity of the world of art history, moreover, not backing an inch from supporting the position of Brandi and theIcr (“le style est l’homme”), reporting since then a never-changing intolerance for Longhi and an absolute dislike for Pellicioli, the same sentiments that still appear in 1994, almost half a century later, in an interview with him: “What is surprising is that such a character [Pellicioli] was held by Longhi in the palm of his hand. And that is certainly rather curious. Anyone who wanted to write a history of restoration in Italy would have to come to terms with this reality. That is, that even in the 1940s and 1950s, the major art historians had ideas about restoration that were absolutely nonexistent from a technical point of view, so they brought along characters, considered charismatic, but of no competence.”

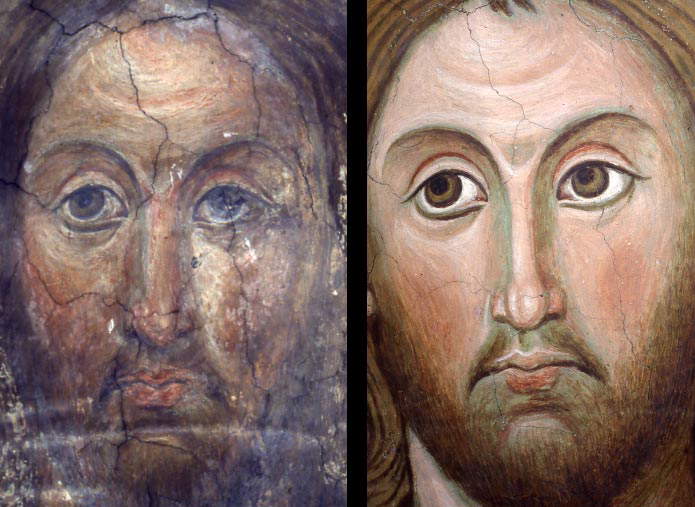

Nor can we rule out, about the reasons for that controversy, Longhi’s wanting to oppose one of the central points of Brandi’s thinking on restoration, the preservation of patina in paintings. The one that in 1949 made the Sienese art historian take a very harsh stance against the cleaning of Italian paintings on wood panels carried out at the National Gallery in London between the late 1930s and the mid-1940s, the same ones that already in 1946 had raised alarms collected in an article in the “Times.” A controversy that he ignited with the famous essay The Cleaning of Pictures in Relation to Patina published in 1949 in “Burlington Magazine,” an intervention that opened a vast debate in European and American art criticism on the subject of cleaning, thus giving undisputed and just international prestige to Icr. Patina that in London had been radically removed, believing restorers and art historians that scientific investigations - it still happens today, moreover - exempted them from reflecting on what they were doing, starting by disregarding at all the position of historical technical treatises on the point. A mistake that Brandi, on the other hand, does not make in the restorations he leads to the Icr. Starting with linking the remains of original varnish discovered on some paintings under restoration at the Icr, among them Giovanni Bellini’s “Pala di Pesaro,” with the entry “Patena” in the “Tuscan Vocabulary of the Arts of Drawing” published in 1681 by Filippo Baldinucci: “Patena. Voice used by Painters, and they otherwise say skin, and it is that universal darkness which time makes appear over paintings, which also sometimes favors them.”

Two data that demonstrate, the first, that still in those years physically resided on a certain number of paintings remnants of original varnishes not otherwise interpretable except as “patina”; the second, that already in the seventeenth century patina was considered by artists a well-defined technical and aesthetic datum. And it is another great merit of Brandi to have demonstrated the fundamental importance of the knowledge of historical technical treatises in restoration also to make sense of scientific investigations, so as to limit as much as possible the margins of error in the interpretation of both analytical data, as in cleaning interventions. And it would be interesting to know what the Sienese art historian would say today about the increasingly radical cleanings that are being carried out with superintendent professors and chemists who ideologically boast of the “certain exactitude” of scientific investigations with respect to what historical technical treatise says, while the opposite is almost always true.

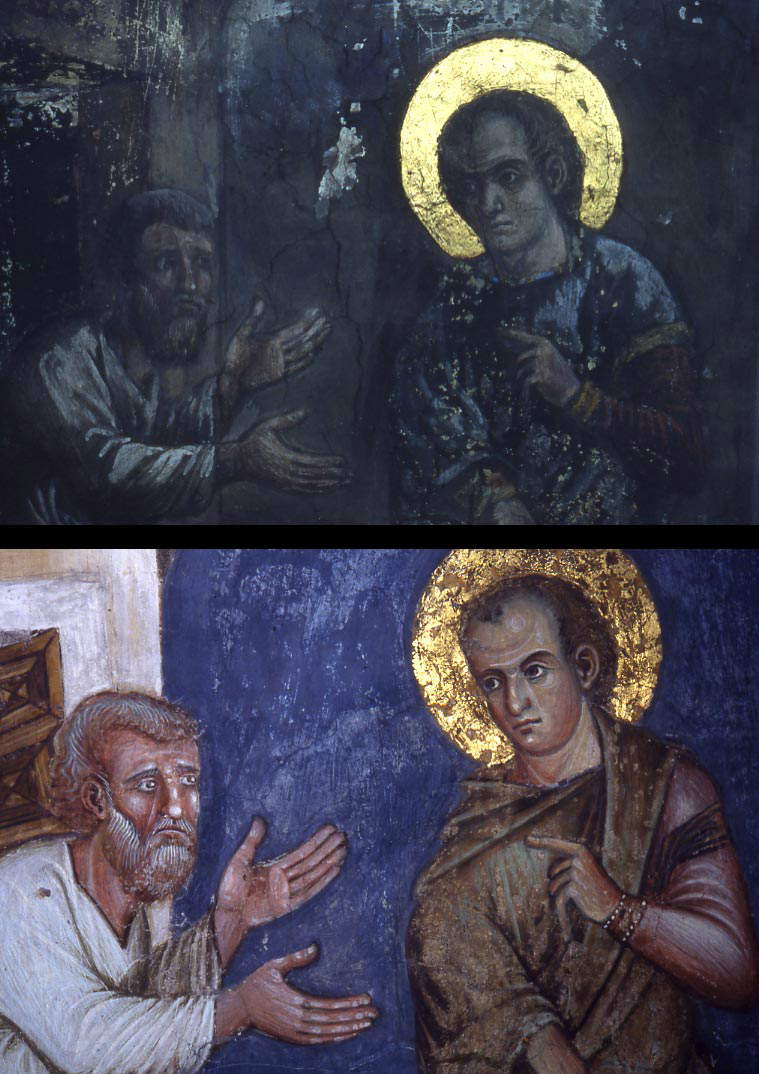

Parma, Metropolitan Baptistery

Parma, Metropolitan Baptistery

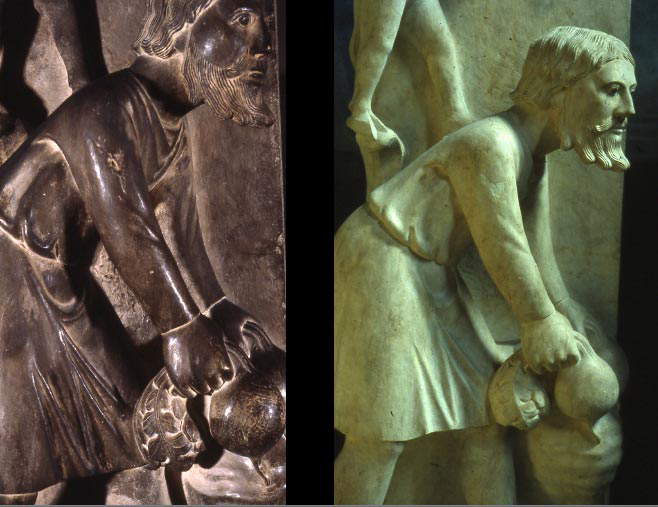

All this in the face of Longhi, who in 1940, about the restoration of the church of Santa Sabina, in Rome, had instead debunked the problem thus (already in “armed peace” with Brandi?): “The cretinous love of patina which is then nothing but filth, that which the ancient master never dreamed of budgeting for in the future,” confirming eight years later the same concept in the cited article in the “Corriere d’Informazione.” This he evidently ignored the existence of that entry in the “Vocabulary” of the Florentine cruscante, or skipping it in one leap. What would be moreover in keeping with the special managerial autism of the however great Piedmontese art historian. A head-on clash between Longhi and Brandi that is also the result of the never-ending contrast between the two ways in which modern restoration has basically moved. Saying it very quickly, the way of antiquarian remaking not to be confused with the antiquarian science already used in sculpture in the fifteenth century: exemplary in this is the account made by Vasari of the restoration “in style” carried out by Donatello of an ancient sculpture with a Marsyas. Antiquarian restoration and that has the first conscious and documented critical station, thus foundational of modern critical restoration, at the end of the seventeenth century with the intervention on Raphael’s frescoes at the Farnesina conducted by Giovan Pietro Bellori and Carlo Maratti who restore the missing parts of the figures starting from the ancient statuary models used by Urbino and taken up by Maratti.

The other way, the historicist way, which originated in the second half of the nineteenth century with Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle and Camillo Boito and descends from there to Brandi and Argan. The way for which restoration is in itself a critical act in its bringing the work back to the authentic lesson, thus never compensating for the parts that had deteriorated or been lost over time except by making the integration visible ex post, for example by reconstructing it with vertical strokes (Brandi’s “hatching”). Restoration of paintings and sculptures that in the nineteenth century became definitively an autonomous profession with the spread of private collecting, thus becoming restorers as a special arm of art historians: just two examples, Giovanni Morelli and Cavenaghi and, as noted above, Pellicioli and Longhi. Autonomous profession sanctioned as such by the publication in the same year 1866 of two restoration manuals: one by the Sienese, but in fact Florentine, restorer Ulisse Forni, the other by the Bergamo restorer Giovanni Secco Suardo.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.