James Ensor, painter and printmaker, was born in Ostend, Belgium, in 1860, developing his aesthetic identity amid the great artistic revolutions of Europe between the 19th and 20th centuries. He oscillated between Impressionism and Symbolism, but never fully adhered to either movement: to the Impressionists he shares only the meticulous and profound study of the color range and luminosity he observes in nature, of Symbolism he appreciates the decadent and vaguely dreamlike atmospheres, the repertoire of macabre subjects, but he will never succumb to the fascination with symbols, allegories and the game of deciphering, which are instead central to the work of the French and German Symbolists of decadentist orientation.

An artist characterized by acomplex personality , in perpetual inner and outer tension marked by difficult relationships and irreconcilable visions that increasingly distanced him from his environment, James Ensor remains today one of the most intriguing figures of the European art scene between the two centuries and, more than anything else, an artist of extraordinary modernity. Modernity that can be found in his profound nonconformity to an art system still dominated by academic norms; in his unique style, which not only has the merit of emerging in an era already marked by enormous cultural changes, but will even anticipate theExpressionism and the future avant-gardes of the twentieth century; and modern are his works, particularly the series devoted to the theme of the mask, since they are capable of communicating at all times to a universal audience by leading the interlocutor to question himself and his own contemporaneity. That of the mask, a constant leitmotif in James Ensor’s production, derives from popular folklore and the Carnival tradition in Flanders, but not only. The attention to the concept of covering one’s face goes back first and foremost to his childhood period, which Ensor spent in the family souvenir stores in which he breathed in and became fascinated by the frivolous and discreet beauty of exotic and bizarre objects such as travel trinkets, shells and lace, stuffed animals, old books and engravings, Chinese porcelain and, indeed, folk masks and disguises. From there springs in him a hidden attraction to the mask and its multiple planes of interpretation, which he also nurtures through his interest in Asian and Western theater, beginning with the Commedia dell’Arte.

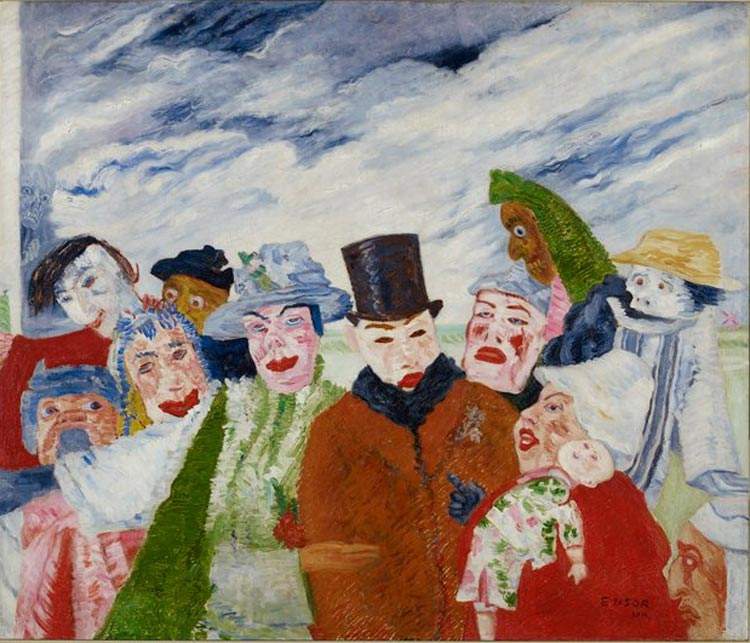

This iconography, appearing as early as his early works in 1887, would develop into a recurring tópos throughout Ensor’s oeuvre and characterize some of his major masterpieces. While in certain scenes the mask lies on the ground, resting on top of ordinary objects or hanging on the walls, like a fragile shell emptied of its concealing power and therefore devoid of functionality, in later works it emerges in all its symbolic force and as an engine of ambiguity. In its most explicit appearances, the mask is amplified and forced to the point of becoming an obsessive and haunting image that proliferates in the space of the painting and transforms faces, figures and human features into unreal, claustrophobic and distressing visions (this is the case in Ensor aux masques, a self-portrait of 1899). Among the many variations on the theme, a prominent work is The Intrigue of 1890, among the most enigmatic scenes in theentire Ensor repertoire.

The painting has been owned by the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp since 1921, along with thirty-seven other canvases by the artist that now form the world’s most authoritative collection of James Ensor’spictorial work. Thanks to the contribution of Xavier Tricot, author of the 1992 Catalogue raisonné des peintures, we now know that Ensor’s total output includes eight hundred and fifty works on the pictorial side alone, in addition to the numerous engravings left by the Belgian master.

On the surface, the scene in TheIntrigue leaves little to theimagination: the context is that of a ceremony and, according to a theory now universally accepted by critics, it would be specifically the controversial marriage between James Ensor’s sister and a Chinese art dealer, identifiable in the two figures in the center of the scene, namely the bride and the groom. The man, distinguished by a mask showing a pale complexion and vaguely Asian features, wears a very elegant top hat that matches well with the nuptial attributes of the woman at his side, a hat adorned with flowers and a bouquet in his hands. Around the couple, a huddle of figures who are also masked accentuates the catalyzing presence of the bride and groom: the group of people wear masks that enhance their ungainly, animalistic faces, curling their large mouths into eerie grins and replacing their eyes with small, dark, vacant, lifeless slits. Some of the characters in the scene, then, present clearly human disguises while others have more the appearance of monsters or supernatural entities: on the right, for example, the skull of a skeleton with a prominent lower jaw stands out; farther on, a figure with large eyeballs turns his gaze to an indefinite point beyond the representation, and equally mysterious is the yellowish face peeking out from behind the group on the left side, flanked by another figure with a deathly pale face and two dark, gloomy eyes.

There are a number of elements in thework that can guide in theinterpretation of thework. The first element is undoubtedly perspective: Ensor depicts the scene from a frontal point of view, leaving us with the choice of whether to identify with the role of outsider spectators, who hypothetically stumbled upon a wedding ceremony and attracted the attention of the revelers by being without disguise, or to become observed observers and thus, on a more dramatic and paradoxical, hostages of a group of figures concealed behind disturbing masks who, recovering the folklorisitic motif of Carnival, would then become an allegory of the tragicomic character of human comedy.

Masks, then, as a representation of human nature and the corruption, vice and deviance of man’s interiority. This ambiguity is confirmed by the presence in the lower right corner of a head with a very pronounced aquiline nose: because of the position it occupies in the scene, slightly distanced and rotated from the other characters, it is impossible to determine whether this figure is masked and therefore joined in the procession, or whether it too is a casual spectator, just like us observers. Hence we immediately come to a second hypothesis: is it possible that the figures in front of us are not masked, and those that appear as masks are rather the real faces of the revelers? James Ensor, on the other hand, gives no clue as to the possibility that these are disguised, except by accentuating their clothes and faces with garish colors and emphasizing their forms, painting pale complexions to suggest a state of decomposition, and complexions of unnatural hues.

By now, however, there has crept up on us the doubt that what we have before us is ahallucination, a ghostly or monstrous or fantastic vision, in which nothing is real and everything is possible: even the idea that in the ensorian universe the absence of mask is the real anomaly. And then the viewer not only finds himself observed, but feels the discomfort of being judged, accused, persecuted as not conforming to the norms of the prevailing reality. Here suddenly beings, entities without identity, seem to stare at us as paying spectators in a circus of cruelty on whose stage we, that is, the normal factor, become buffoons, phenomena or monsters for display.

This reversal of perspective is reinforced first and foremost by the composition of the work: the presence of the characters in the environment is almost total, and they form a compact block that limits our view and sucks us into a neutral but not neutral space, devoid of spatial and temporal coordinates. In this regard, note how the small demonic face that emerges from the side edge of the scene on the left, perhaps deliberately left barely outlined, contributes to the unreal, dreamlike feel of the scene. Moreover, the viewpoint of the observer is imperceptibly lower than the optical plane of the revelers, and these, arranged in a wedge formation headed by the married couple, exert a compact interplay of gazes that converge on the observer himself, with claustrophobic effects that provoke in the observer a sense of menace and disquiet.

On a technical level, James Ensor differentiates the elements of the work by creating a highly effective contrast: on the one hand, he creates the background with light, muted tones in order to make the atmosphere as indefinite and hazy as possible; he contrasts it with a warm and intense palette for the characters, whom he depicts in brightly colored clothes and masks that are jarringly contrasting with each other. Moreover, the colors are frantically poured onto the canvas by means of rapid, schizophrenic brushstrokes that make the scene vibrant and charged with restless mystery, as if foreshadowing a dramatic event on the verge of happening. In spite of the visual hodgepodge of clothing and textiles that appear layered in indistinguishable ways, the faces instead show sharp details that stand out against sickly, bestial faces evoked with acidic colors and that create a sinister, yet extraordinarily intriguing effect. Indeed, although we feel compressed and hunted in the background of the scene, our eyes remain firmly chained to the mocking gazes of the monstrous figures who leave us no physical or mental escape, yet provoke in us a sublime disturbance that is impossible to repel.

If so, the enigmatic nature of The Intrigue might resolve itself into a direction for anyone who faces the work: to take up the challenge of measuring oneselfagainst one’s own nature and becoming aware of one’s human limitation. Indeed, what else would the masked group embody if not a metaphor for the different faces of our nature, a parade of monsters that are none other than the inner monsters with which one struggles during the course of existence? Like a kind of magic mirror, James Ensor’s work would thus restore to man his fragmented, indeed multiplied image in a variety of identities and versions of his unconscious that finally appear for what they really are, without any mask. Here the paradox, and the absolute modernity, of James Ensor’s work is revealed.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.