In 1540 the sculptor Leone Leoni (Arezzo, 1509 - Milan, 1590) was working as an engraver at the papal mint. The artist had embarked early on a brilliant career, played out in various Italian centers and a prelude to the international success that would lead him, by the end of the decade, to enter the service of Emperor Charles V. His stay in Rome, the city to which he had landed in 1538, would last no more than two years. The insults he received from Pellegrino di Leuti, a papal jeweler who boasted that he had undermined Diamante, the sculptor’s wife, drove Leoni to violently defend the family’s honor. The artist, responsible for scarring the jeweler’s face, was sentenced to amputation of his right hand. The intercession of some prominent figures determined, fortunately for European art history, that the sentence was reduced to a period of forced labor on the galleys. The oar duty would soon be discontinued, for having passed from Genoa the vessel on which he was on, the sculptor was freed by Andrea Doria (Oneglia, 1466 - Genoa, 1560) in March 1541.

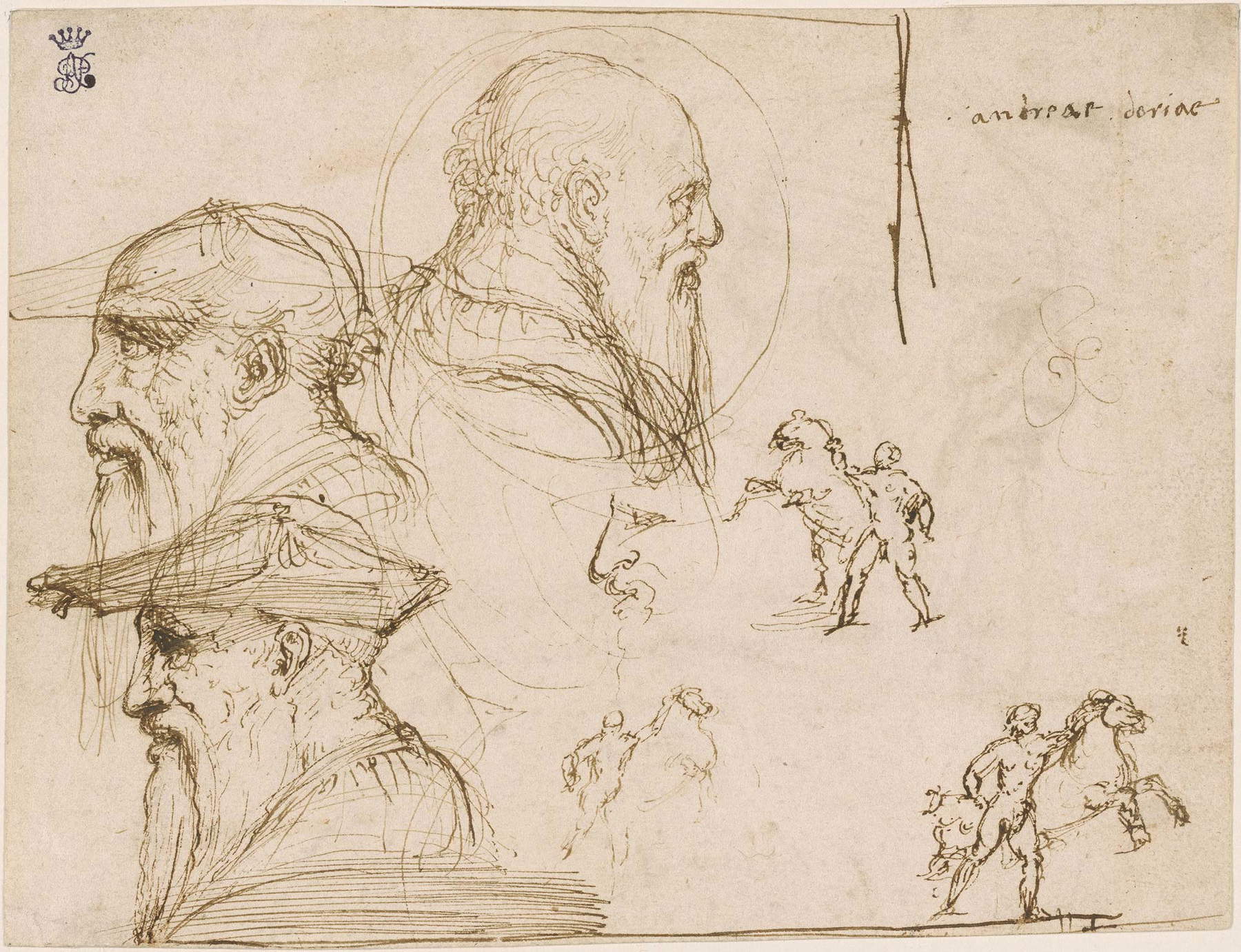

As a reward for the benevolent gesture, Leone Leoni would effigy Doria, who became his patron (as well as savior ), in several medals and bronze plaques. The Genoese man’s profile is preserved in the numerous surviving specimens, and testifies to the image of an elderly man, swaddled in the garb of a condottiere and recognizable, by the presence of the trident, as a lord of the sea.

Andrea Doria was born in Oneglia, a center of western Liguria, in 1466. Belonging to a patrician lineage responsible for writing several pages of Genoa’s history, but linked to a cadet branch of the dynasty, the nobleman embarked on a military career at an early age, having been orphaned. In the service of several powers, the first of which was the papacy, Andrea spent some years away from the highly complex dynamics of late 15th-century Genoese politics. Returning home at the dawn of the new century, in a reality now subject to the interference of the king of France, the nobleman began to orient, against the backdrop of the wars of Italy, his activities as an entrepreneur of war on the maritime juncture. His ever-expanding squadron of galleys would become, during the third decade of the century, the fundamental tool for controlling the routes of the western Mediterranean.

It was in this context that, in 1521, Andrea Doria completed the first purchases of land and buildings in the hamlet of Fassolo, located outside the city’s western walls, with the intention of erecting his residence there. This operation, carried out at an advanced stage of his life, is considered as the start of an artistic commissioning project that would be concreted, starting in 1528, with the arrival in Genoa of Pietro Bonaccorsi known as Perin del Vaga (Florence, 1501 - Rome, 1547).

The year 1528 represented a pivotal date in the history of Genoa, such that it constituted a point of no return on the city’s political, social, economic and artistic juncture. In that process, the leading role played by Andrea Doria was immediately recognized: before the nobleman could proceed to celebrate his achievements with the construction of his residence, it was the Republic itself that decreed the erection of a statue in his honor. The commission was given to the Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli (Florence, 1488 - 1560): however, the artist did not complete the work. The marble block, left in a sketchy state and witnessing forms far from “that excellence” that the commissioner would have expected, was placed in Carrara, in the Piazza del Duomo, where it is still kept.

In the early months of 1528, Genoa was under the military rule of Francis I of France (Cognac, 1494 - Rambouillet, 1547), in whose service Andrea Doria had been operating since 1522. The contract between the commander and the French monarch having failed, making a “volte-face,” Doria signed an alliance with Emperor Charles V (Ghent, 1500 - Cuacos de Yuste, 1558). The Genoese proceeded to free the city from foreign domination and proclaim the freedom of the Republic, a fact moreover guaranteed by the agreements signed with the Habsburg house. On the strength of his support, he launched an institutional reform capable of appeasing the endemic factionalism of the city’s oligarchic system and surviving, with a few adjustments, until the fall of the Republic at the end of the eighteenth century.

The role Andrea Doria assumed in the new political equilibrium, made clear by his choice not to hold top posts, was reflected by the location of his residence, set at the edge of the city. The appearance that the villa took on at the end of the construction and decorative phase promoted by Andrea is unclear, as the form in which it appears today only partly reflects the original layout. The building complex, decorated externally and internally, was set in a system of gardens that determined its connection with both the hillside and the sea.

In the Lives of Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574), a text that records numerous details about Andrea Doria’s patronage, the circumstances of Perin del Vaga’s landing in the Ligurian capital are clarified. The Florentine painter, who was born in Florence and moved to Rome in his youth, boasted an alumnuship, a reason of undoubted prestige, at theatelier of Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520). A decisive factor in the artist’s abandonment of the papal city was the devastation wrought by the Lansquenets in 1527, which he experienced firsthand. “While the ruins of the Sacco had destroyed Rome and made the inhabitants and the Pope himself depart from it,” Vasari recounts, the embroiderer Nicolò Veneziano, who was in Liguria in the service of Andrea Doria, “persuaded Perino to leave that misery and send himself to Genoa.”

The painter’s arrival at the Dorian site would have allowed the condottiero to be able to make use of a complete artist, to whom perhaps a role in defining the architectural appearance of the palace was due. This was accessed through a vast atrium whose entrance was framed, on the northern facade, by a majestic Carrara marble portal, designed by Perino and made, according to information provided by Vasari, by Giovanni da Fiesole and Silvio Cosini (Poggibonsi?, 1495 - Pietrasanta?, after 1549). The latter artist, formerly a collaborator of Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564) on the construction site of the Medici Chapels, supervised the execution of many of the stuccoes that went on to frame, beginning with the vaults of the atrium, staircase and loggia, the ceilings of the rooms frescoed by Perino.

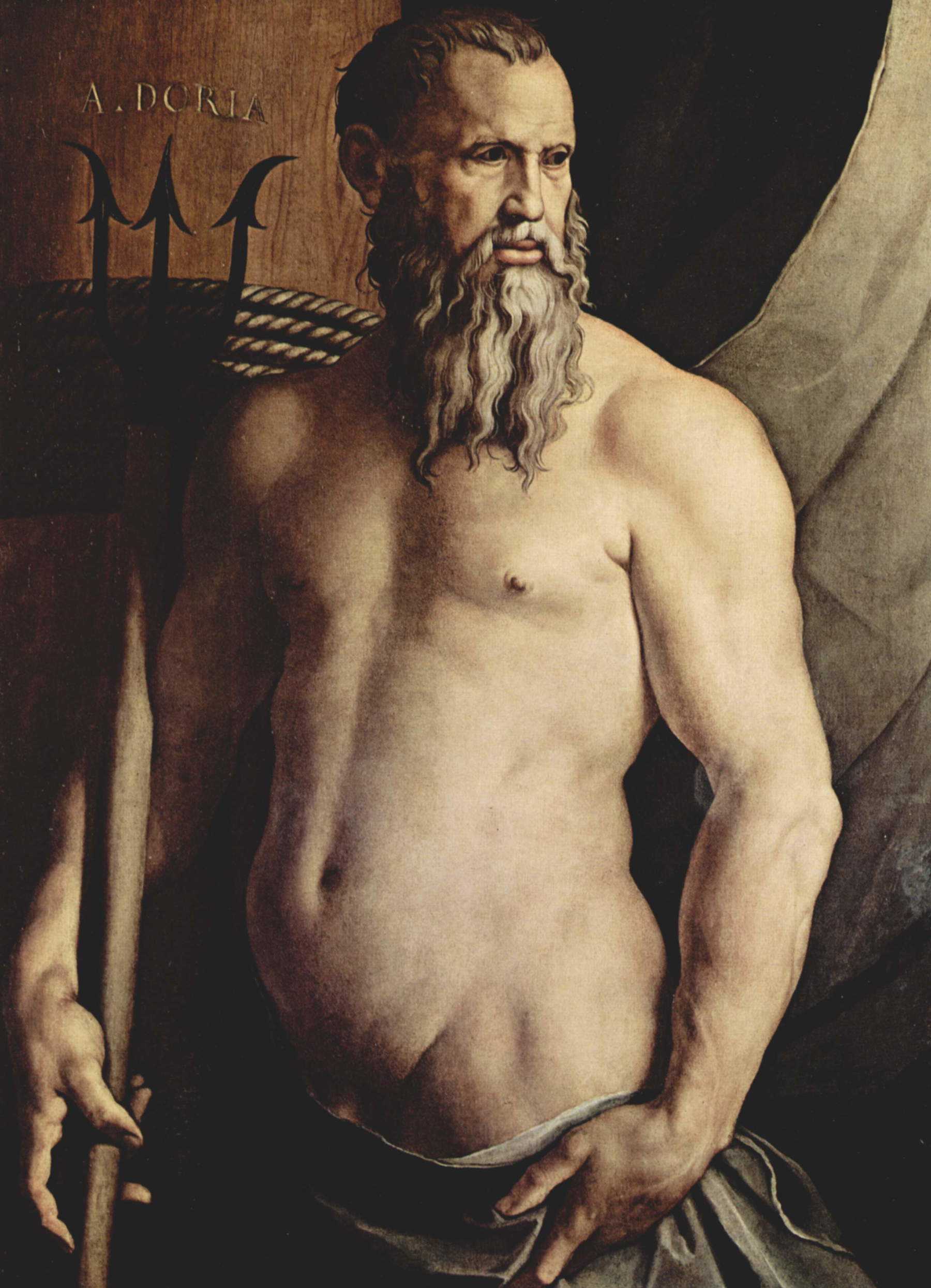

The knowledge of the many Renaissance courts that Andrea Doria frequented in the years of his youth must have been a determining factor in the choices employed in the construction and decoration of his residence. On the other hand, the condottiero, then in his sixties, had certainly come into contact with various artists: suffice it to think of the circumstance for which, on the eve of the Sack of Rome, he was portrayed by Sebastiano del Piombo (Venice, 1485 - Rome, 1547) in an extraordinary painting, commissioned by Pope Clement VII (Florence, 1478 - Rome, 1534) and only later received at the residence of Fassolo. The pope, on the other hand, was not the only figure to desire an effigy of Doria for his own collection: Paolo Giovio (Como, 1483 - Florence, 1552), who was building up a collection of images of illustrious men in those years, had Agnolo Bronzino (Florence, 1503 - 1572) portray the Genoese. The canvas, which came to the Brera Art Gallery in the late 19th century, constitutes one of the most iconic images of the admiral, depicted by the Florentine painter in a vigorous nudity that identifies him as Neptune, god of the sea.

The artistic temperament that matured in Raphael’s workshops thus made its entrance into the House of Doria, and thus into Genoa. The cycle of frescoes and stuccoes coordinated by Perin del Vaga, supplemented by numerous tapestries (woven in flanders) to which he himself provided cartoons, constituted one of the largest decorative complexes of early 16th-century Europe.

Andrea Doria’s residence soon became a worthy place to host illustrious figures, including the emperor himself, who first stayed in Fassolo in 1529. In the following years, Charles V bestowed the admiral with numerous honors: in 1531 he was awarded the fief of Melfi, which earned him the title of Prince, from which he derived the name, for his residence, Villa del Principe. In the same year, the awarding of the prestigious Golden Fleece determined the choice of subjects with which the southern façade was frescoed, which involved, in addition to Perino, the painters Giovanni Antonio de’ Sacchis known as Pordenone (Pordenone, 1483 - Ferrara, 1539) and Domenico Beccafumi (Montaperti, 1486 - Siena, 1551). No trace remains of that cycle, dedicated to the figure of Jason.

Perin del Vaga’s Genoese sojourn was interrupted, the palace’s decorative campaign having ended in 1536. In the following years, Andrea’s attentions went to focus on the church of San Matteo, a building owned by the Doria family, a temple of the memories of the great exponents of the lineage and the chosen burial place of the prince of Melfi. The church, which still retains its ancient medieval facade, underwent a comprehensive restoration in its interiors beginning in the 1940s.

The opportunity to redefine the spaces of the ancient building was offered to Doria by the move to Genoa in 1539 of Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (Florence, 1507 - 1563). The Florentine sculptor, trained in Michelangelo’s circle, had landed in the city to make that honorary statue of Doria that the Republic had commissioned in vain, in the previous decade, from Baccio Bandinelli. The nobleman did not miss an opportunity to make use in turn of Montorsoli’s chisels, who was entrusted with the management of the San Matteo worksite. Montorsoli’s workshop, which availed itself of the collaboration of Silvio Cosini, put in place the decorative structure of the presbytery, the cross vault and the crypt, inside which Andrea’s tomb was placed. These rooms were covered with polychrome marble and decorated with all-round sculptures, bas-reliefs, and stuccoes, which together constituted an unprecedented model for the local artistic scene.

That of providing for his own burial constituted a just concern for a man who was over seventy-five years old at that date. Dying a nonagenarian, Doria promoted, in the last phase of his life, a new decorative intervention in the church of San Matteo. In the late 1650s, painters Giovanni Battista Castello known as the Bergamasco (Gandino, 1509 - Madrid, 1569) and Luca Cambiaso (Moneglia, 1527 - San Lorenzo de El Escorial, 1585) were found working in the naves, which, redefined on that occasion architecturally, were covered with stucco and enriched with frescoes. In the painted scenes in which the two artists, the main protagonists of painting in the second half of the 16th century in Genoa, found themselves engaged on the same scaffolding to conduct, in creating different scenes, a real artistic competition, probably encouraged by the Prince himself.

The figure of Andrea Doria, admiral of the imperial fleet and considered in Genoa as Pater Patriae, established a new paradigm of commissioning in the city. On the one hand, the nature of the artistic interventions he promoted, concreted in the construction of his suburban villa and the restoration of the church of San Matteo (located instead in the heart of the ancient city), and on the other hand the caliber of the artists involved, represented a novel conduct for the local nobility.

Andrea called masters from different centers, knew how to take advantage of opportunities allowed by his role (such as the one that arose with the release of Leone Leoni), and, living many years, had the opportunity to make use of different generations of painters, architects and sculptors. The works they created in the workshops he promoted constituted indispensable models for the masters active in the city and brought about a change of course in the city’s artistic affairs. The activity of Luca Cambiaso, a Genoese painter trained in turn on the pictorial texts of the villa of Fassolo in the Dorian church of San Matteo, may be a clear example of the influence exerted by the products of the condottiero’s patronage.

While the church still remains intact in its original medieval context, the expansive spaces of Andrea Doria’s residence, endowed with extensive gardens, were radically downsized when, in the late 19th century, the new demands of urban mobility curtailed significant portions of it. The villa’s name has since been recalled to anyone entering the city from the railway station that rose next to it, Genoa Piazza Principe.

This contribution was originally published in No. 3 of our print magazine Finestre sull’Arte Magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.