It has been a few years since Costanzo Ciano’s mausoleum in Livorno was last in the national news. It was 2015, to be precise. At the time, Daniele Caluri, the brilliant cartoonist who invented Don Zauker, had proposed painting it in the colors of Uncle Scrooge’s warehouse. Ideal size, ideal shape. So here’s the rendering ready, shared via social media: all you have to do is call someone to assemble the scaffolding and someone else to cover it in paint. Discussions, a few pages in the newspapers, a petition on Change gathering thousands of signatures, the mayor giving his approval, nostalgics getting indignant, and then the matter died down almost as suddenly as it had lit up, being reduced from a restitution project in pectore to a summer controversy (it was October, but in Livorno summer lasts six months if not longer). And Ciano’s mausoleum went back to doing the only thing it has known how to do, for more than eighty years: the pharaonic unfinished, the square of white concrete that, when you pass along the Antignano waterfront, can be seen far away in the middle of the Montenero brush, on the slope of Monte Burrone.

When the long era of damnatio memoriae ended, much began to be said and written about the mausoleum. It was studied for a long time, plans sheets were found, what to do with it was discussed. The fact is that today Ciano’s mausoleum has become, basically, a ruin. And as such it fascinates us. It has become a ground of universal enmity, Georg Simmel would have said. Enmity between the parts and the whole, between nature and the human being who tried to dominate it. And here, the monument has also become a ground of enmity between human beings and their history.

It has remained that way since the regime collapsed. A material paradox that takes on the brackish face of the sea, a concrete flow that disfigured the green profile of the hill, the most expressive emblem of the irrational ambitions of a regime that, in the midst of the war and amid the creaks that announced its imminent collapse, until thelast would not give up its work of “fascist sanctification,” scholar Federico Scaroni called it, to be celebrated by means of a disproportionate cenotaph that everyone would see from the coastline. A monument to the rhetoric of the fascist, rather than to the hierarch. That majestic monument would never have been born, and today in the woods above Livorno it remains only a forgotten wreck that the bush is trying to cover, to take back. There is no sign marking it. Neither on the seafront, nor along the road leading to the Montenero shrine: you get there by a dirt lane that begins when you have almost reached the top of the hill. And it is unmarked simply because from the very beginning it has ceased to be a meaning-bearing object for the city, for the community. Of course: it is noticeable, if you look away from the sea, when you walk on the rocks that were dear to the Macchiaioli. It is hard not to notice a twelve-meter white spot attached to a hill. It is there, period. But it is as if it does not exist.

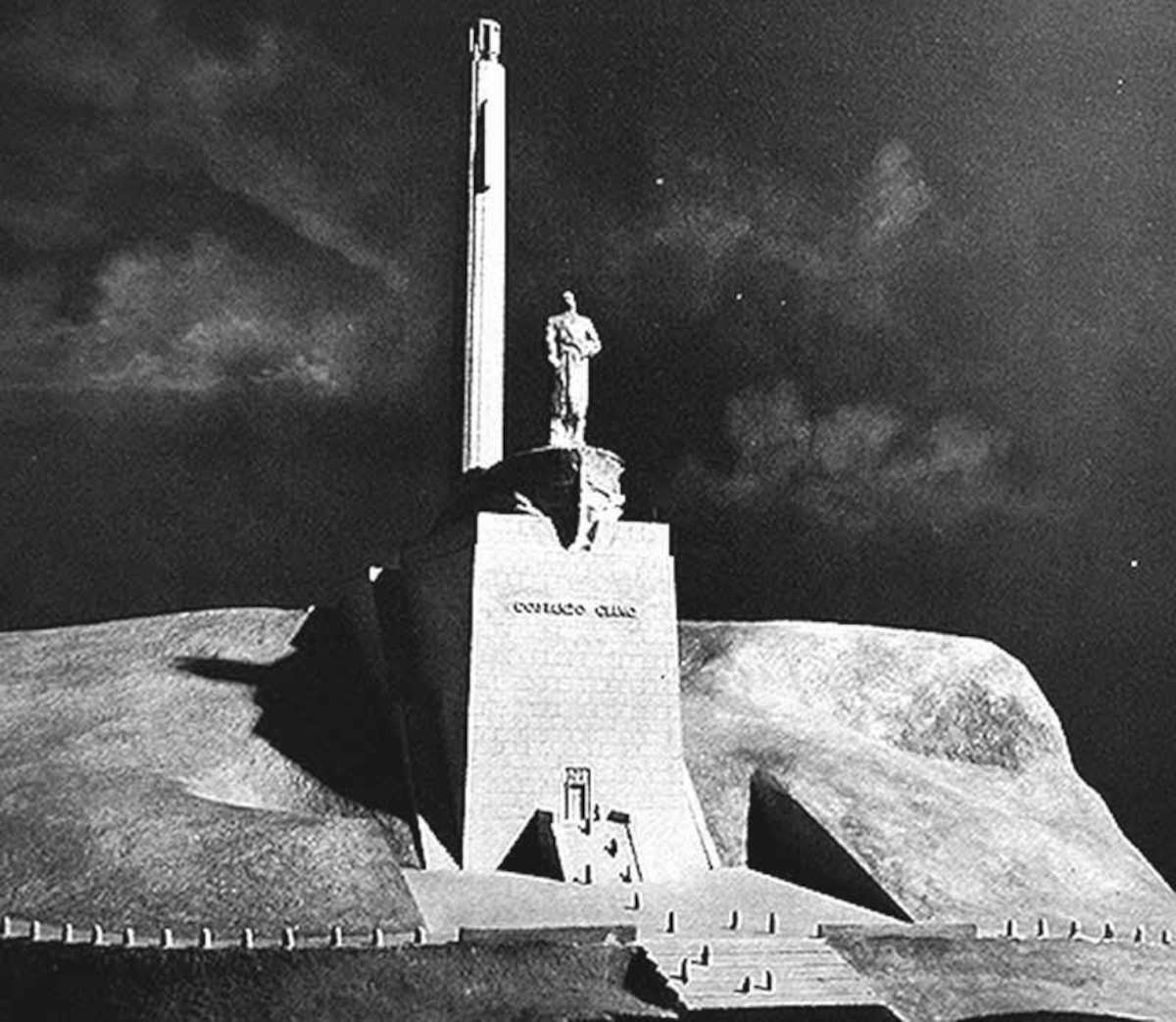

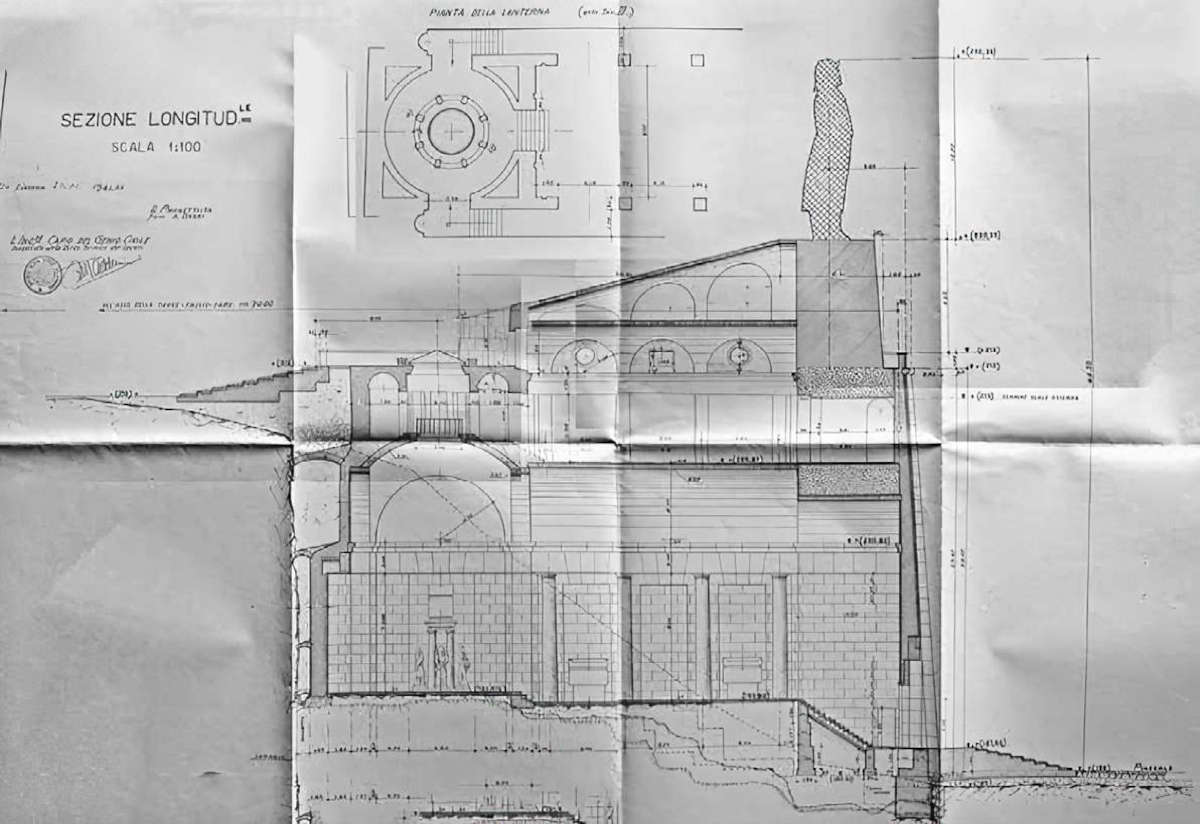

It was to be one of the regime’s most scenic monuments. A huge plinth of about fifteen meters that would have housed, on the top, the colossal statue of Costanzo Ciano, twelve meters high: he would have been depicted in the guise of a sailor, driving a MAS. A kind of modern equestrian statue, with the torpedo-armed motorboat in place of the horse, to eternalize the admiral in the guise of the hero of Buccari. Inside, the sanctum sanctorum with Ciano’s urn surrounded by statues of two sailors and two balilla. On either side of the mausoleum, two long stairways, among the few things completed, would have led visitors to the terrace where Ciano’s statue would have stood atop his torpedo-armed speedboat. Behind, a lighthouse in the shape of a fascio littorio fifty-four meters high. In short, not exactly the height of sobriety. But it matched well with the regime’s truncated emphasis.

The idea of honoring the hierarch’s memory with a grand and imposing work came from the then mayor of Livorno, who after Ciano’s death in 1939 opened a public subscription to raise funds for the undertaking. Not exactly the most opportune time, with a Europe that would collapse in the war a few months later, but the podestà managed to get the subscription going with a base of 100,000 liras, a little more than 100,000 euros today. The chronicles of the time report that within a short time, between private donations and public resources, the subscription had already reached half a million, which is why the podestà was convinced of the goodness of the project, and already at the end of the year he entrusted the project to Arturo Dazzi from Carrara, who was among the most loyal and acclaimed sculptors of the regime. It was the artist himself who insisted that Gaetano Rapisardi, who would be in charge of the architectural parts, also be involved, so that Dazzi would only be responsible for the sculptures and the design of the project. A granite from the island of Santo Stefano, in Sardinia, was chosen for the statues: a company from Genoa, Schiappacasse, was entrusted with the opening of a special quarry, in Villamarina, where the pieces of the colossus would be worked. The Telegraph, Livorno’s newspaper, with the usual pomposity of the phrasing of the time, did not fail to heap praise on the project: “The Leghorn hero who in his broad generous chest welcomed the breath of the sea , was to have for his monument a special platform from which he dominated the vast expanse of the Tyrrhenian Sea near which he opened his eyes to the light, of which he lived by the work of his own, to which he devoted himself, studying in the Royal Naval Academy to prepare himself for the struggles on the sea. [...]. At the foot of the hills runs the Aurelia, and whoever from Rome comes to the Lido labronico will find the solemn and magnificent herm straight up on the prow of a ship stretched out to the world. And that will be the sign that Livorno is near. A meandering street from the shoreline will ascend to the monument, which in its haughty solitude, in the severe lines in which sculptor Dazzi designed it, will tell of the greatness and glory of the Hero of the Sea, high vigilant over the Lido of Italy. Behind the statue will rise a farò that in the loneliness of the nights will shine far over the placid or bellowing waves in the storm, keeping watch: the very soul of the Hero who will watch over Livorno and the Tyrrhenian Sea. The sturdy and severe conception of this monument, so adherent to the figure and spirit of the great Son of Livorno, and so set in the picturesque place chosen as an altar between sea and sky to celebrate there an immortal glory , responds perfectly to the intention of paying homage to one who could not, with the usual forms, celebrate himself.”

It took a year to draw up the final design, and the construction site started when Italy was already in the midst of the war, in 1941, and when it was clear to everyone that things would take a long time, assuming work did not stop. There remains a letter from Rapisardi to Dazzi, dated June 17, 1942, with the fulminating account of the reply that the site watchman had given to the architect eager to know whether the prediction of completing the work within a year was in any way well-founded. To the question, the watchman failed to answer. Rapisardi then asked him if it was possible to finish the work at least within two years. The guardian’s reply, “You know better than me.”

The watchman was right: in a year’s time the construction site, which was already going slowly, would be permanently halted. Italy was at war. There was a lack of money, earmarked for the war effort. There was a lack of manpower, because boys were leaving for the front. There was a shortage of fuel for transportation, which was needed to power military vehicles. And there was also a shortage of transportation, because it had become impossible to move the granite blocks from the island of Santo Stefano to the coast of Tuscany without getting caught by the British ships manning the Terrain. Everything was missing, in short, and on July 25, 1943, as Mussolini was arrested, the new government gave orders to suspend all public works deemed unnecessary. And even the construction site of the monument to Ciano was being abandoned. The regime had managed in time to pull up one floor of the mausoleum and one half, roughly, of the lighthouse-tower, and to have Dazzi complete three of the statues that would hold Ciano’s tomb inside the crypt. Those few valuable materials that had already been installed (basically slabs of bardiglio marble and statuary flown in from Carrara to cover the interior walls) were probably looted already during the war, when the Germans established a coastal observation point on the mausoleum (and before they left, they would have blown up the stump of the lighthouse that the regime had managed to put up). In the middle of the Montenero woods today remains the concrete cube. Two sailors completed by Dazzi, on the other hand, decorate a small garden on the seafront in Forte dei Marmi, where the sculptor had his studio: when the heirs donated to the municipality what the sculptor still had in his workshop, evidently memory of the function of those statues had been lost, and their public installation raised no problems. And from guardians of Ciano’s tomb, the two sailors have become guardians of the Versilia nightclubs overlooking the seaside boulevard. The only completed balilla is still in Forte dei Marmi, in another small park, in front of a parking lot. In the Villamarina quarry, however, fragments of the Ciano statue remain, left where they were when the quarry was also abandoned.

The laurel, viburnum, and fig trees that grow wild in the Montenero scrub now guard the entrance to the unfinished building. Before you get there, not far from the entrance to the mausoleum, lies on the ground what remains of Ciano’s sarcophagus, entirely covered with the graffiti of graffiti artists climbing up here, abandoned amidst the underbrush. Amid the scribbles and profanities left with spray paint on the marble remains of the urn one can still read the hierarch’s name. The interior was to be divided into two floors: visitors, arriving from the outside, would have first encountered a vestibule that would have led them to the crypt, the sanctum sanctorum intended to house Ciano’s ark and which’was arranged to contain also the remains of his family members in the chapels arranged along the side aisles, and then, again from the vestibule, by means of stairs and elevators it would have been possible to access the upper floor, where it was planned to open a museum with the relics collected to celebrate the life and exploits of Costanzo Ciano. The second floor was never realized, and what remains today is only the crypt.

It was meant to resemble a pagan temple. The monumental neoclassical forms are still legible: a large basilical hall with a nave and two side aisles, covered by a barrel vault supported by columns of green marble: the columns would have accompanied visitors to the apse, covered by a dome, where the ark would have been placed. All devoid of decoration, all set on essential geometric forms: austerity was the hallmark of Fascist classicism. The transition from the nave to the apse was designed according to an allegorical sequence of shadow and light: “passing from the darkness of the first room to the grazing light of the apse,” wrote architect Luca Barontini, “one had to as if to be blinded by the ’light of the eternal world,’ which was supposed to make Ciano’s ark stand out.” A sort of small version of Étienne-Louis Boullée’s visionary temples. Or a tacky reduction, of Boullée’s temples.

Today the light is the natural light of the sun shining on the uncovered environment: the dome was never built. In place of the ark grows wild vegetation, which has also begun to claim the interior of the monument. On the ground, on the floor, a kind of garbage dump, the traces of the only people for whom today this space still makes sense: junkies, graffiti artists, drifters who come here to bivouac, lovers evidently disinclined to romance and who are content just with a place to mate without too much trouble and without minding the squalor that serves as an alcove for their loves. For everyone else, Ciano’s mausoleum is nothing anymore. It may fall under that label of “dissonant heritage” invented in the 1990s by John Turnbridge and Gregory Ashworth, although the expression has been disputed: any fragment of the past contains within itself values that are difficult to reconcile with our own, but not for everyone does this latent potential unlock (which is why other scholars have preferred to speak of “heritage dissonance,” attributing some form of active potential to monuments). In order not to have to engage in an academic discussion, we could limit ourselves to deeming Ciano’s mausoleum a controversial and conflicting remnant, difficult to handle because among its walls, among the butts of what is left, among the ruins lurks a recent and atrocious past, the darkest pages of Italy’s history are hidden. And for this reason, ever since the mausoleum stopped being considered unmentionable, there has never been an end to the discussion of what to do with it, with this wreck. Paint it as a repository for Uncle Scrooge. Convert it back to something else, a war memorial, anything else as long as it obliterates its primal destination. Just fix it up, restore it.

Perhaps the best thing to do, however, is to leave it as it is. A ruin that the hill is eating away at. A historical testimony. A fragment of the past embedded in the present, which to our eyes has much the same effect that the ruins of ancient Rome buried among brambles, holm oaks, and pine trees must have had on eighteenth-century Grand Tour travelers. Of course, they did not find spray-painted lettering, discarded cigarette packets and used condoms there, but time moves on. On the ruins it does what it has to do. And here there is nothing to salvage, to restore, to fix. There is, if anything, to leave the mausoleum where it is, the most eloquent allegory of the system that produced it, the symbol of a regime that dreamed of dominion over land and sea and collapsed into rubble. Leave it as it is. And let time do its own thing.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.