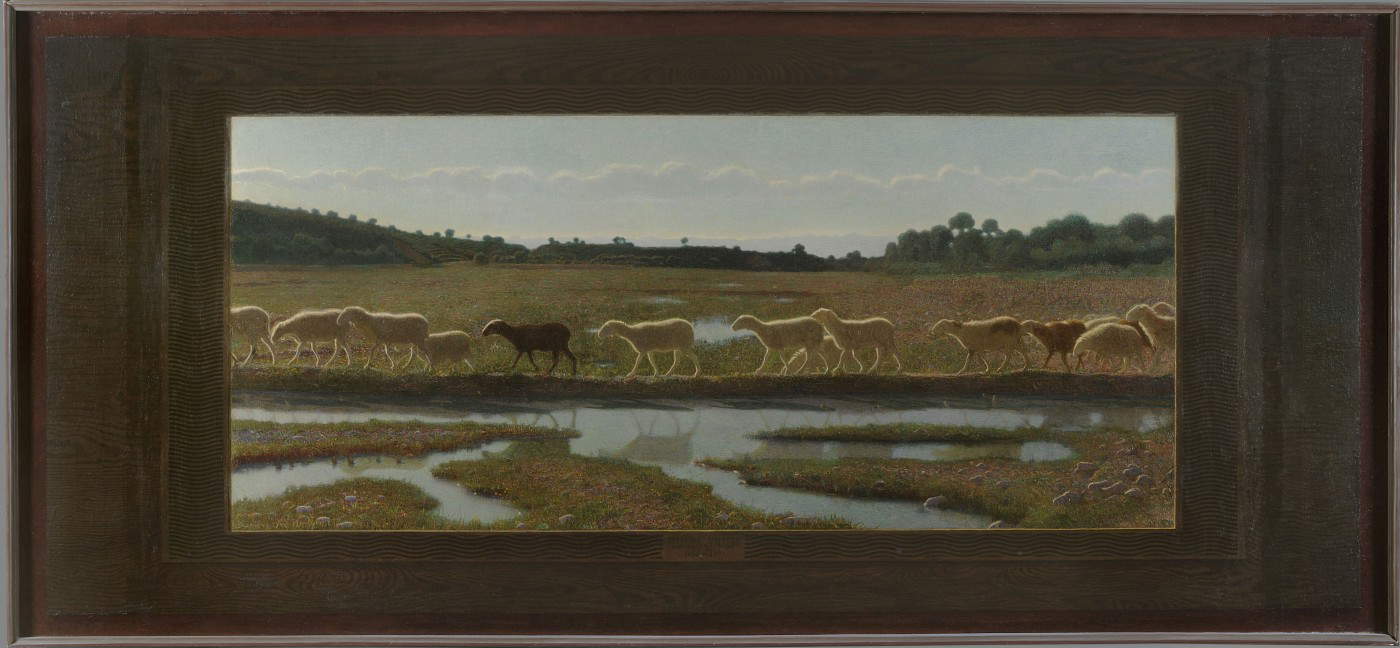

“The illustrative symbol of man in his family and social organization is the flock,” Folco Portinari wrote. “The flock is the people, whether one wishes to give it a negative or a positive sign.” One can start from here to read one of Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s seminal texts, Lo specchio della vita, a painting that the Alexandrian artist first presented at the 1898 Promotrice di Torino, after working on it for at least four years. It is an apparently simple work, which at first appears to the eye of the observer as a rural idyll: a flock of sheep proceeds in a line, among the marshes, in the Piedmont countryside, parading in front of a forest, in the light of a clear and crystalline morning, illuminated by a radiant sun. They stand one behind the other on the bank of the Curone stream, in places the painter must have seen and traveled thousands of times. Some of them are mirrored in puddles, we do not perceive either the beginning or the end of the flock, we do not know how many animals are in it, we do not know when their gait will end, but we do know that these sheep are all moving in the same, single direction.

It is a work that demonstrates Pellizza’s accomplished adherence to Divisionist poetics and that, as was usual with the paintings of the most astute Divisionists, is loaded with symbolic references. And here the painter is at the height of his closeness to Symbolist instances: he had intended his work to be a commentary on some tercets from Dante’s Purgatory , those in which, in Canto III, the poet observed the souls proceeding before him: “As the sheep come out of the enclosure / a una, a due, a tre, and the others stand / timidette atterrando l’occhio e ’l muso; / e ciò che fa la prima, e l’altre fanno, / leaning on her, s’ella s’arresta, / semplice e quete, e lo ’mperché non sanno; / sì vid’io muovere a venir la testa / di quella mandra fortunata allotta, / pudica in faccia e ne l’andare onesta”.

|

| Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Lo specchio della vita (E ciò che l’una fa, e le altre fanno) (1895-1898; oil on canvas, 132 x 291 cm; Turin, GAM - Galleria Civica dArte Moderna e Contemporanea, inv. P/1017) |

Pellizza, who was coming from a period of intense literary studies completed in Florence, had focused on a verse: “e ciò che fa la prima, e l’altre fanno.” He had affixed it to the title of the work to explicate the concept that informs it, and he had reiterated it clearly in a letter sent to Ugo Ojetti (“it serves to make known that if there is expression in my work it is not due to chance but has been achieved consciously by the author,” the artist wrote). Nevertheless, critics were perplexed: nothing could be reproached about the fine analytical rendering of this piece of rural serenity, which in terms of harmony of form, balance of light and shade and purity of color is among the highest proofs of Pellizza’s art, but its allegorical value was not immediately understood. Ugo Fleres, for example, could not understand why Pellizza had cloaked a foreshortened marshy landscape crossed by a flock of sheep in such mystery. “Notice that the undulating curve,” he had written in a review, “marked by the backs of the sheep illuminated in tangent light by the sun, is similar to that of the mountains in the distance and to that of the clouds parading over the horizon. Is this a symbol? I gladly admit it; but it is also a poverty of line, and a bore.” But Pellizza could not exempt himself from the call that his art imposed on him: for him, art could not be just a matter of shapes and colors, but had to take equal charge of the condition of the human being (“I feel that now is no longer the time to make Art for Art’s sake, but Art for Humanity.” so he wrote, in May 1895, to his friend Angelo Morbelli as he began to look forward to the Mirror of Life). The truly descriptive, for the tormented painter from Volpedo, is but a mere beginning, a reservoir of images, a vocabulary from which to draw words and references to be translated into thoughts, naturally well-ordered in a composition that is formally unimpeachable. And it is in this encounter between the real and the ideal that the deepest meaning of Pellizza’s art must be found.

At the time of the elaboration of the Specchio della vita (Mirror of Life), Pellizza was also awaiting the realization of the Fiumana now at the Pinacoteca di Brera, that is, the canvas that would lead to his best-known masterpiece, Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate). And the flock of sheep, therefore, must be interpreted taking into account the background of a painter attentive to the social claims of contemporary workers, a painter who had not yet turned thirty, who intended to do “good” with his art, by his own admission, and who, in order to pursue this good, observed reality with his eye of a peasant, born and raised in the countryside of the Val Curone, and who by nature is inclined to look at things with supreme goodness, without ever having known the resoluteness and vigor of the workers’ unrest of the industrial cities. There is always a profound vein of poetry in Pellizza’s works: it is true of The Fourth Estate as well, and it is even more evident in The Mirror of Life, which is certainly aided by the total absence of the human figure, an absence that moreover becomes functional in conveying a sense of universality.

Pellizza is essentially saying that that flock is us. But this is not a statement to be understood in a negative sense: the line “what the first one does, and the others do” does not resolve itself into the meaning of the rabble of sheep who follow the herd leader. There is no sign of peremptoriness, negativity or contempt in the painting, there is no obvious moralism, there is not even denunciation, there is nothing to support such an interpretation, which would be exceedingly superficial, far from the painter’s true intentions: Pellizza looks with obvious tenderness and heartfelt sympathy at the flock parading through the countryside. He seems to identify with that line of animals walking, calm and tame, in the country morning. His gaze is the same as Dante’s: the souls of Purgatory are “little sheep,” “shy,” a “demure” and “honest” flock. It is a painting that speaks of beauty according to an almost fifteenth-century, idealized feeling. It is therefore impossible to misrepresent the meaning of Pellizza da Volpedo’s work.

And so to understand the meaning of this work it is necessary to return to Portinari: “the flock is the collection of meek creatures, who must be guided, who seek refuge in the fold toward which they are led, the protected place. In its helplessness, the flock is blessed and therefore divinely safeguarded in this quality of renouncing subversive risk. It is perhaps more than any other a cardinal theme, in connection with nature and sociality.” Pellizza’s Mirror of Life is such in the true sense of the expression: the pools of water scattered in the bucolic stillness of Piedmont reflect the human condition, the sheep are the intent humanity called to share the experience of a path fraught with difficulties, of which neither the beginning nor the end can be seen. For the painter, one can only move forward, waiting for salvation. It is the same humanity that, a few years later, will animate The Fourth Estate.

Of course, there could be no shortage of those who reproach Pellizza for the idea of a resigned, meek and contained humanity, perhaps resigned, as well as what could appear as a discovered contradiction between aspiration and intention. But that flock is humanity as Pellizza sees it, and to read his reasons it might be difficult not to empathize. For, in his own words, those sheep are human beings caught as they face “the coming and going of all the events of the world.” United by their spirit of aggregation, which for Pellizza is thus to be read positively. A work intended to dispose the relative to an approach marked by a “great serenity,” the disposition necessary to reason about the “alternation of good and evil, of joys and sorrows.” So there is life in its most metahistorical and constant essence, free of references that make it subject to actualizing interpretations or biased readings. There is, said the artist, “a great idea of life.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.