Immobilized to a wooden chair in a room in the half-light, while onlookers watch with ill-concealed voyeurism. The unfortunate man is writhing in pain and almost seems to hear them, the screams. Behind him is the apathetic executioner carrying out his cavadent trade. A grotesque genre scene from 1608, the one attributed to Caravaggio, whose conventional title could only be The Caveman. That of the dentist is, arguably, one of the trades most feared by young and old alike, but although it has often been mistreated, it has its roots in the oldest history.

The problem of toothache plagued human beings when it was still believed to be a divine curse. Recently, in fact, studies have been carried out on the teeth of skulls from about 25,000 years ago, and evidence of tooth decay has been found. One of the earliest written sources, however, dates back to a Sumerian text from 7,000 B.C.E. that described tooth decay as a result of the work of “tooth worms”-at that time they were treated by skilled craftsmen using bow drills. Instead, the first dental filling, made of beeswax, dates back to 6,500 years ago in Slovenia (it was discovered in 2012 on the remains of a fractured tooth, probably with the aim of relieving pain), but the great flowering of ’dental art will occur in Egyptian times. At Saqqara, the tomb of a man named Hesi-Ra was discovered, who lived during the reign of Djoser and was a member of a class known as Phostophori, whose job was to cure the sick. A papyrus was found here that speaks of oral disorders and its remedies, such as replacing diseased teeth with healthy ones and joining them together, by means of a golden thread.

Medical discoveries grew by leaps and bounds as the centuries passed, and treatments were patiently and steadily perfected. During the 6th and 4th centuries B.C.E., Hippocrates and Aristotle wrote about dentistry, trying to create a scientific basis for the understanding and subsequent treatment of oral diseases. Around 100 B.C., Celsus, a Roman writer and physician, also narrated extensively about oral hygiene in his important compendium of medicine, covering various topics, such as the stabilization of soft teeth, procedures to be followed in case of toothache and jaw fractures. And the Etruscans also did their egregious part when they refined dentures using gold crowns and fixed bridges.

A giant step backward, unfortunately, will occur from the 12th century, when a series of papal edicts prohibited monks from performing any kind of surgery, bloodletting or tooth extraction. After these edicts, it was barbers who took over the surgical duties of the far more learned monks, and in 1210 a Guild of Barbers was founded in France. Throughout history, barbers, evolved into two groups: actual surgeons and lay barbers who performed routine services such as shaving and, indeed, tooth extraction. A curiosity: it was during the Middle Ages that the “barber’s pole,” the one with the colored stripes, was introduced. It was white and red and was used to advertise the surgical services offered by the practitioner (in particular, tooth extraction and bloodletting).

Today, the word “cavadenti” is used in a derogatory way to refer to a mediocre dentist who was unskilled at his job, but earlier it simply indicated a kind of dentist who, with rudimentary tools, extracted teeth, even in the street, and to work more easily placed a glass or paper ball inside the poor patient’s mouth. And because they often worked in anything but a professional manner, quack cavadents lent themselves well to numerous genre scenes, especially in the seventeenth century. The most famous is, without a shadow of a doubt, the aforementioned Cavadenti attributed to Michelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio. For many years there has been debate about the authorship of the work, and many art historians have well taken both sides. What is certain, however (although not evidence for attributing the work to Merisi), is that in 1638 the inventory of Palazzo Pitti included, “a canvas painting by the hand of Caravaggio painted that one was lifting the teeth of another and other figures around a table (...).” And again, in 1657, the author of Microcosm of Painting, Francesco Scannelli wrote: “Vìddi pure anni sono nelle stanze del Serenissimo Granduca di Toscana un Quadro di meze figure della solita naturaleza, che fa vedere quando un Ceretano cava ad un Contadino un dente, e se questo Quadro fosse di buon conservatione, come si ritrova in buona parte oscuro, e rovinato, saria una delle più degne operationi, che havesse dipinto.” The painting, exhibited at the Pitti Palace, does not aim to unveil hidden meanings of life, but rather to recount, with macabre realism, a true scene that is not at all sweetened.

Particularly interesting might appear to be the self-quotation of the elderly lady irradiated by a very warm light coming from the right, whose face is also present in the very cruel work of Judith and Holofernes. We seem to be witnessing a strange torture in which the cavadent, behind the patient’s back proceeds, with a mocking air, to extract it. All around is arrayed a small crowd of onlookers with distorted and emphasized expressions that seem to emphasize the duplicity of human nature. On one side, some seem to be pleased and nourished by the pain felt by the customer, while others seem sincerely grateful that that torment is not theirs to bear. On the left and in the half-light, a curious and intimidated child leans out, leaning against the table. We seem to be watching a theatrical staging in which expressions must be emphasized and strongly characterized.

We also find dental scenes in the genre painting of the Flemish Theodoor Rombouts who lived in Italy between 1616 and 1625 where he also worked for Cosimo II de’ Medici. He looked to the Caravaggesque prototype, so much so that he replicated the famous Lombard artist’s cavadenti four times. Probably a copy, now in the Prado Museum in Madrid, was executed during his stay in Florence, after he had the opportunity to admire Merisi’s example up close. In this canvas, too, the crowd is gathered around the callido cavadenti who turns his gaze to the viewer of the work as if to reassure him, overbearingly breaking the fourth wall. The painted faces are grotesque and extremely extravagant, and the unfortunate man seems a subtle reference to Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by the Ramarro rather than his Cavadenti.

There would be many artists who were strongly attracted to Caravaggio’s revolution and who would not only try to imitate Caravaggio’s style but also the cavadenti theme, as in the case of Gerrit van Hontorst, who probably saw Caravaggio’s canvas in Florence during his stay in Italy from 1610 to 1620. Gherardo della Notte, (as the artist was renamed in Italy), for his interiors warmed by the dim light of candles, was one of the greatest Dutch painters who came to Italy. He had great success between Rome and Florence, becoming one of the most beloved painters of Cosimo II, who was particularly interested in his convivial scenes. Among these is the strange work of 1619-1620 entitled Dinner with Lute Player. Although what has been interpreted by some as the extraction of the tooth is relegated to the edge of the canvas, every detail leads the viewer to turn his or her gaze to the far right, joining the onlookers at the table who giggle softly as they witness the scene (although, looking at the preparatory drawing preserved in Grenoble, what has been interpreted as a cloth to cover the extracted tooth could simply be a forkful of spaghetti, like the ones we see on the table, that the young woman is sticking into the man’s mouth in a goliardic moment).

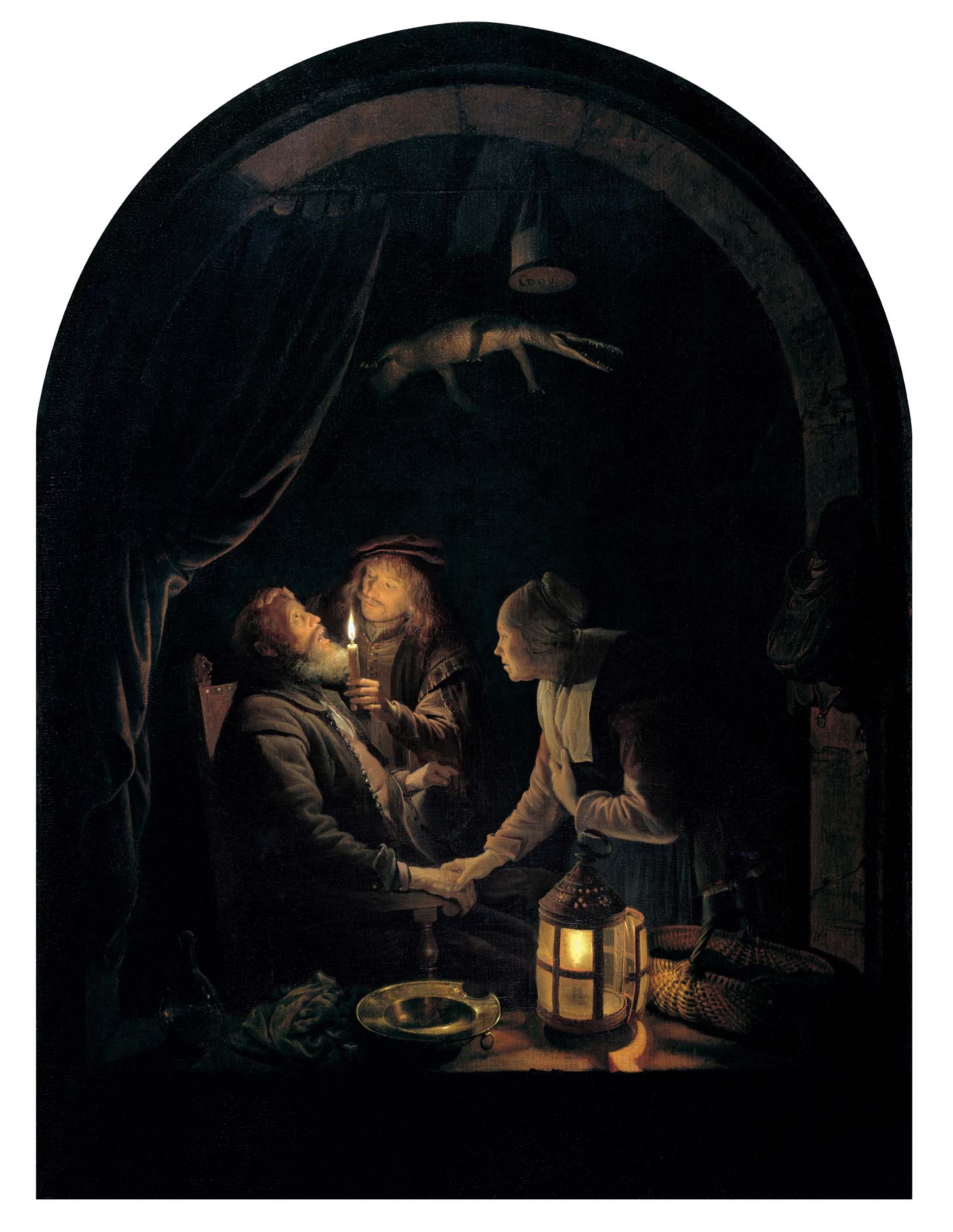

A work that bears a decidedly closer resemblance to the beloved master of light is The Toothpick, preserved at the Staatlische Kunstammlungen in Dresden. In the 1622 painting, a young assistant holds up a candle to help the skilled cavadenti who, sneering, proceeds with the extraction amid the cries of pain of the bearded patient. The witnesses around, not feigning polite disinterest, rush in to watch the operation closely as one of them holds the sick man down.

Dutch painters seem to be decidedly fascinated by the theme of tooth extraction as canvases by Adriaen van Ostade, Jan Miense Molenaer, and Lambert Doomer show. By the latter we get a particular drawing that seems to depict the barber’s trade of cavadenti in an almost photographic manner. The dental extraction takes place outdoors, with the protagonists sheltered only by a parasol. The patient is lying down, leaning against the cavadenti’s chest, and next to the two, an assistant holds a flask. All around, numerous spectators, some interested in the operation performed by the barber and others in the spidering performed by a monkey.

Jan Miense Molenaer also tried his hand at several representations, a charlatan and a real cavadent, respectively. The former is in the Anton Ulrich Museum in Brunswick and shows a charlatan aided by his accomplice playing the part of the patient, and as the crowd flocks in curiosity to observe the mock operation, a man steals birds from the basket of an apprehensive lady. The artist here stages the wickedness of the human soul and the dishonesty of charlatans. But of a different scope is the canvas kept at the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) in Raleigh.

The scene takes place in a brightly colored interior that makes the whole thing curmudgeonly and vaguely amusing. The young patient clasps a rosary in his hands to underscore how, oftentimes, the prayers of the faithful are in vain, while his face takes on an expression of strong sorrow. Also in an interior is Adriaen van Ostade’s depiction from about 1630, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The cavadent is constantly positioned behind the patient as he is concentrating on the dental operation, and near him, a small assistant promptly hands him a plate. All around, the ever-present interested crowd.

Each of the representations seen so far pillories the poor sufferer, exposing him to the eyes of curious and vile characters, but it would be Gerrit Dou with his Cavadenti (1630-1635) who would restore dignity to the craftsperson, as well as the patient, by placing them in private homes, away from the gaze of overbearing voyeurs. Barbers cavadenti did not always perform beauty and minor surgery outdoors, but often took refuge in the homes of clients to work in peace and quiet. In this youthful example, the canvas is composed of few elements and inhabited by just the two characters facing the faint light profused through the window. Next to the aching customer, resting on the ground, is a basket with foodstuffs with which the farmer will pay, when the work is done, the cavadenti. In the background, a few dimly lit elements such as the skull and violin are used by the artist as memento mori, reminding the viewer of the fleeting nature of life and the suffering that comes with it.

Decidedly more mature is Cavadenti by Candlelight, dated between 1660 and 1665, which depicts an out-of-hours intervention inside the barber doctor’s office, although the heavy curtains around the painting’s outline are more reminiscent of a theatrical scene. The poor man, accompanied by an apprehensive woman who may be his wife, turns his gaze, concerned, to the strange hanging crocodile. An object, this one, at the time found in many barbers’ and surgeons’ offices, as a status symbol, as a sign of belonging.

Each of these artists tried to faintly lighten, to turn a small spotlight on a profession with a past made up of lights and heavy shadows, and, perhaps, that is precisely why the dentist is still so feared. Its history has not been an easy one, and surgeons have had to see their noble craft mocked by quacks and impostors, and above all, there were many, many centuries of profound patient suffering. From the 16th century, fortunately, dentistry timidly began to be considered a science and slowly began to make its way into the minds of intellectuals and scholars, who sought to improve it.

We would have to wait until 1899, however, when dentist Edward Hartley Angle was credited with turning orthodontics into a dental specialty. Angle also founded the first school of orthodontics (Angle School of Orthodontia in St. Louis, 1900), the first orthodontic society (American Society of Orthodontia, 1901) and the first dental specialty journal, giving this very specialty a bright future.

The author of this article: Francesca Anita Gigli

Francesca Anita Gigli, nata nel 1995, è giornalista e content creator. Collabora con Finestre sull’Arte dal 2022, realizzando articoli per l’edizione online e cartacea. È autrice e voce di Oltre la tela, podcast realizzato con Cubo Unipol, e di Intelligenza Reale, prodotto da Gli Ascoltabili. Dal 2021 porta avanti Likeitalians, progetto attraverso cui racconta l’arte sui social, collaborando con istituzioni e realtà culturali come Palazzo Martinengo, Silvana Editoriale e Ares Torino. Oltre all’attività online, organizza eventi culturali e laboratori didattici nelle scuole. Ha partecipato come speaker a talk divulgativi per enti pubblici, tra cui il Fermento Festival di Urgnano e più volte all’Università di Foggia. È docente di Social Media Marketing e linguaggi dell’arte contemporanea per la grafica.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.