The name of Rosalba Carriera (Venice, 1673 - 1757) is among the most important in 18th-century art. She approached painting miniatures and small pastel portraits because, according to the mentality of the time, they were, in painting, the most suitable achievements for a woman, and it was her delicate and elegant pastel portraits that made her one of the most influential, famous and in-demand artistic personalities in Europe. Rosalba Carriera began painting on her own, in the family environment, and then given her talents she was in the workshop in Venice, her hometown, by Giuseppe Diamantini and Antonio Balestra: within a few years she became an independent artist who was able to win the attentions of art collectors, diplomats, and sovereigns all over Europe. His art was always very true to itself and never experienced a decisive evolution, but his career did not lack some significant masterpieces.

Compared to the other states of Italy, the Republic of Venice has always had a more liberal tradition, and this, in some ways, was also valid with regard to the role of women, so much so that some scholars have been led to think that it was in Venice, beginning in the second half of the seventeenth century, that trends were born that anticipated feminism, also due to the fact that Venice saw the presence of certain figures such as the writer Lucrezia Marinella (Venice, 1571 - 1653) who signed a treatise entitled La nobiltà et eccellenza delle donne co’ difetti e mancamenti de’ gli uomini, a 1600 work in which she discussed why, according to the author, women would be superior to men. It was an almost unique case in the Italian context: to the figure of Lucrezia Marinella could, however, also be added that of Arcangela Tarabotti (Venice, 1604 - 1652), who matured her feminism as a response to the fate that befell the women of her time, because in most cases they were either given in marriage or ended up in a convent, and in both cases often and willingly against their will, and Arcangela Tarabotti’s fate was precisely that of ending up in a convent, a decision that the girl resented badly and triggered the denunciation of the society of the time that we read in her writings, the best known of which is theInferno monacale, in which Arcangela Tarabotti describes the lives of young women of nobility and bourgeoisie who, because of family choices, were forced to take vows.

In the eighteenth century, the social condition of women was not very different from that described in Arcangela Tarabotti’s work, however, we know that, for example, at the legal level women in Venice had more concessions than those in other states: for example, they could choose to whom they entrusted the education of their children, and in addition they attended parties, theaters, salons, and intellectual circles. Therefore, we should not imagine Venetian women as shut-ins at home or in convents, because they had quite wide spaces of freedom for the time. Moreover, some women like Rosalba Carriera managed to build a different path for themselves: in fact, Rosalba Carriera found a way to establish herself through painting, she who was already a woman of considerable cultural depth and from a wealthy family. So, in eighteenth-century Venice, women, while maintaining a subordinate role compared to that of men, were able to carve out considerable space for themselves to become major protagonists on the one hand of social life and on the other of a cultural renewal and a renewal of thought that already starting in the seventeenth century has led some scholars, for example Patricia Labalme, an important historian of the Venetian Renaissance, to speak of feminism ante litteram.

|

| Rosalba Carriera, Self-Portrait with Sister’s Portrait (1715; pastel on paper, 71 x 57 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

Rosalba Carriera was born in Venice on January 12, 1673 to Andrea Carriera and Alba Foresti. The family was of middle-class extraction: her father held administrative roles for the Republic of Venice and her mother embroidered lace. Around 1690 Rosalba attended the workshop of the painter Giuseppe Diamantini (Fossombrone, 1621 - Venice, 1705), who was her first real master (the name of Giovanni Antonio Lazzari is also mentioned, but we are not sure about the latter). Soon afterwards he also studied with Antonio Balestra (Verona, 1666 - 1740). The first certain reports of her work in pastel, the technique that would make Rosalba famous and in demand throughout Europe, date from 1703. At the same time, the artist began her independent activity. In 1705 she was admitted to the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, after presenting the Fanciulla con colomba. In 1708 she made a portrait for King Frederick IV of Denmark, while the following year she executed her self-portrait preserved today in the Uffizi Gallery: she apparently sent it as a gift to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III de’ Medici.

In 1720, the artist stayed in Paris where he stayed until early 1721 and where he was able to work for Louis XV of France, who was still a child at the time, and for the regent, Duke Philip II of Orleans. In Paris he kept a Diary in which he noted with great accuracy all the events that occurred during his stay. In 1723 he made a brief stay in Modena where he painted portraits of the Este princesses. Instead, the two portraits of his friends as well as fellow painters Marco and Sebastiano Ricci date from 1724. Around 1725 he painted the Madonna of the Correr Museum in Venice, probably the most famous of his rare works with a religious subject. Around the same year he began painting the Four Seasons for Joseph Smith now in the Royal Collection in Windsor: the allegorical theme would be one of the most successful of his production. It was in 1730, however, that he painted the portrait of Faustina Bordoni. During the same period he stayed for six months in Vienna with Emperor Charles VI.

In 1741 he began the cycle of the Four Elements preserved at the Corsini Gallery in Rome. It will be finished in 1743. Three years later, in 1746, she contracted an eye disease that in the following years would lead to blindness despite several operations and force her to abandon her painting activities. She painted around this year one of her most famous self-portraits, the one in which she would portray herself as Tragedy. Rosalba Carriera passed away in Venice on April 15, 1757.

|

| Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1708; pastel on paper, 36 x 30 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

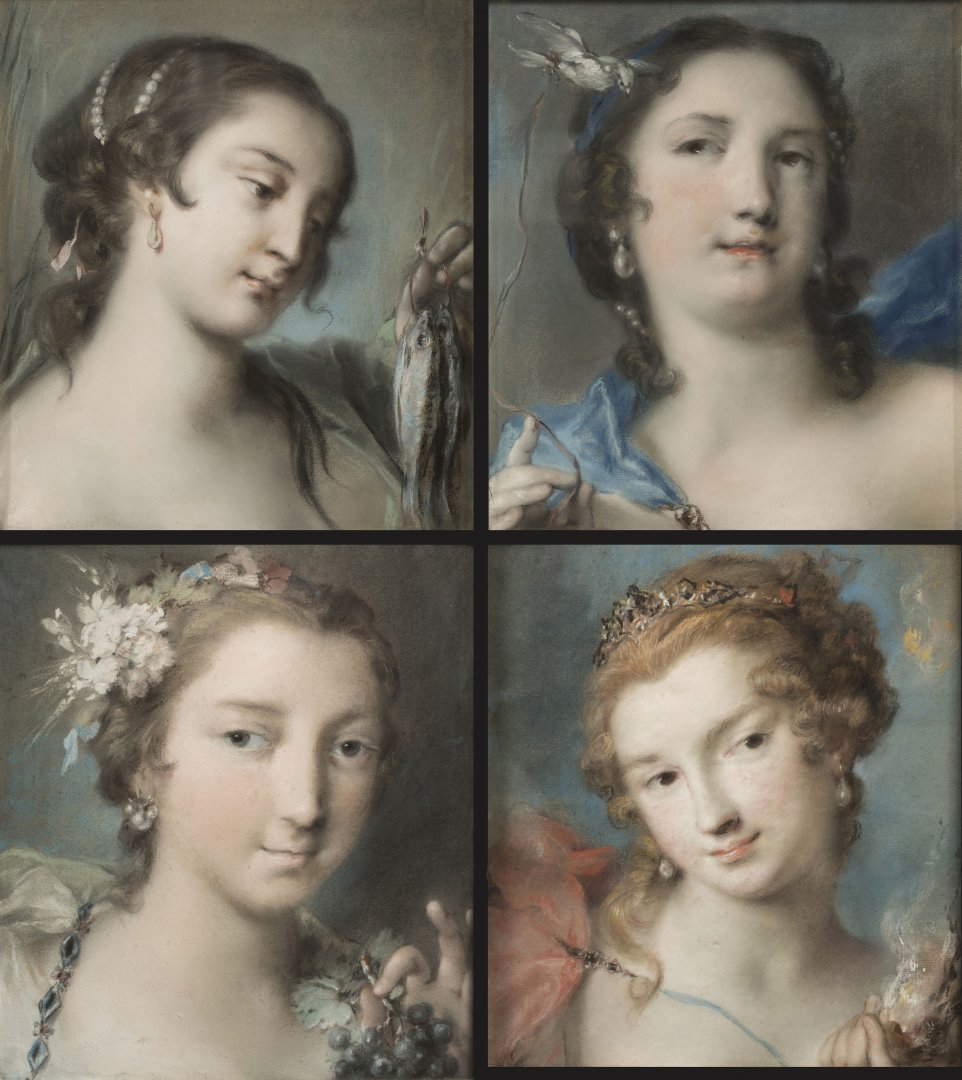

| Rosalba Carriera, The Four Elements (1741-1743; pastel on paper, 33.5 x 30 cm each; Rome, Galleria Corsini) |

According to the studies of art historian Cristiano Malamani, Rosalba Carriera approached the pastel technique in the early eighteenth century at the suggestion of Christian Cole, secretary to the English ambassador in Venice, and the first reports of Rosalba’s work with pastels date back to 1703, the year to which a letter from an enthusiastic Giuseppe Maria Crespi (Bologna, 1665 - 1747), an important Bolognese artist who had seen some of her work and praised her, saying that to find her a husband suited to her talent they would have to bring back the great Guido Reni. Among her earliest works it is possible to mention a well-known female portrait, circa 1708, kept in the Louvre: Rosalba Carriera’s style is distinguished by its delicacy, the almost suspended atmosphere (and the fact that the subject depicted is a girl, almost a child, only adds to the whole softness of the whole), the palette set on white tones to increase the whiteness of the girl to thus suggest the idea of her innocence (however, pinkish hues are noted on the face that give it greater realism). Moreover, one of the characteristics that made Rosalba Carriera’s portraiture one of the most admired of all time is her ability to penetrate the character’s psychology by capturing their state of mind and returning it to the medium on which she painted. Interesting in this regard is a roughly contemporary painting (from 1708): the subject depicted is King Frederick IV of Denmark, who at the time was staying for a few months in Venice (thus, Rosalba Carriera had already been noticed by an important ruler). Frederick IV moreover had also commissioned Rosalba to paint twelve portraits of twelve gentlewomen chosen from among the most beautiful in Venice, all as miniatures on ivory. In the pastel depicting Frederick IV one can see the care Rosalba Carriera devotes to several details such as the curls of the wig, which, thanks to this technique, appear almost softer, just as if they were real (the king is turned three-quarters and seems sad to us, he has a gaze that conveys melancholy: Rosalba Carriera’s ability to enter the character’s psyche depicts him to us with this sad air, to give naturalness to his expression).

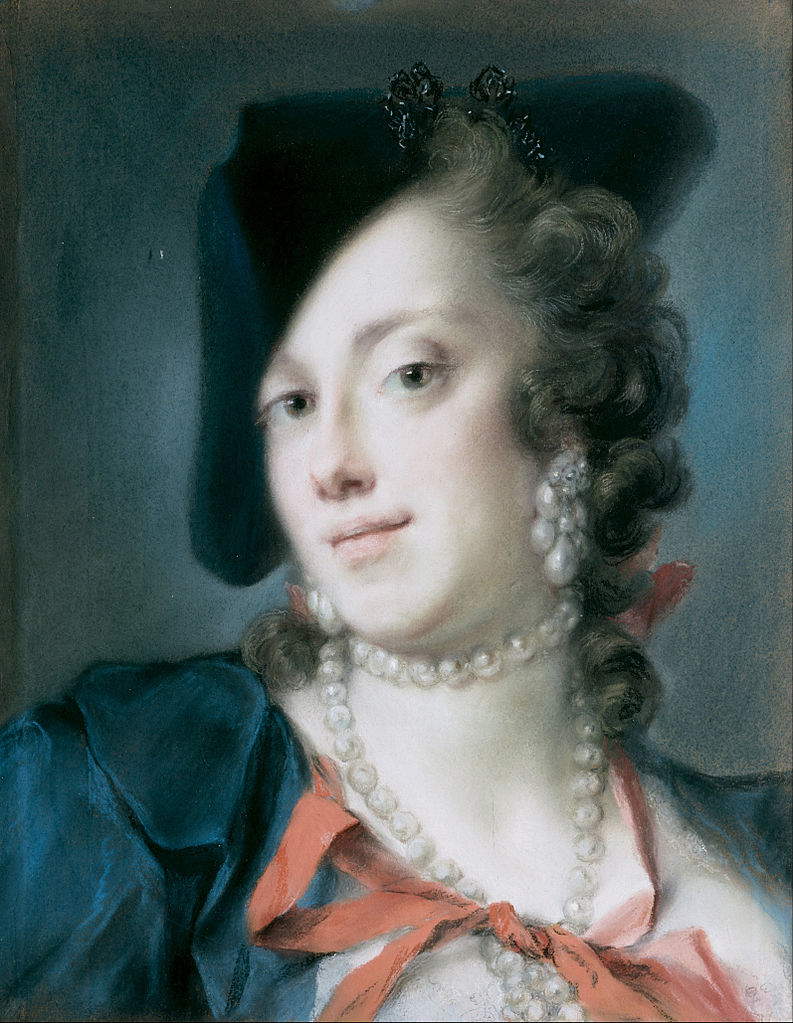

Rosalba Carriera also often tackled allegorical themes, with paintings executed in series or cycles. One of the most interesting cycles is preserved in the Corsini Gallery in Rome and was made between 1741 and 1743: these are pastels on cardboard commissioned by Giovanni Francesco Stoppani, apostolic nuncio to Venice between 1741 and 1743, along with a portrait of her that is now in the Museo Civico in Cremona and another painting that has been lost. It is a cycle having as its subject the Four Elements. The elements are depicted as young women shot in close-up so that only face and neck can be seen (in other cycles Rosalba would have chosen a half-length cut instead), and each of them has an attribute reminiscent of the element they personify (air has a bird flying by her side that she holds by a thread so that it does not fly away, water holds some fish, fire is a red-haired young woman with a small brazier, and earth holds a bunch of grapes, the fruit of the earth). One of the best-known allegorical paintings dates from about 1730 and is in the Art Institute of Chicago: it is interesting because it is not known whether it is a true portrait or an allegory. It is the Lady with the Parrot, whose protagonist is a beautiful mischievous-looking girl, elegantly dressed in a rich pearl necklace and a blue robe, holding a parrot. This parrot is peeling back her robe and allowing a glimpse of the girl’s chest: since the parrot was believed to be a symbol of lust, this painting might just be an allegory of lust, given also the mischievous and inviting expression of the girl depicted.

As mentioned, Rosalba Carriera is best known for her portraiture: there are countless portraits she painted. One very interesting portrait dates from around 1725, is preserved in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, and depicts a young boy whose identity we do not know for sure. The subject may be the son of the consul of France in Venice because he arrived at the Galleries through a bequest from a family descended from the Leblonds, a family to which the consul of France in Venice belonged at that time. One can see the painter’s typical softness, to which is added a renewed study of light that strikes the young man’s face full on and causes a light halo to spread around his head, which then fades into the dark background. Many have likened Rosalba Carriera’s painting not only to that of Guido Reni but also to that of Correggio, with whom she shares grace (Rosalba’s compositions also draw on seventeenth-century Emilian painting. Rosalba’s grace emerges from her art even the effigy is a king, as in the case of the portrait of Louis XV of France. The work dates from 1720, the year of the painter’s stay in Paris, and depicts the king at the age of ten: the delicacy of the child’s face clashes with the solemnity and officialdom of the portrait, one of Rosalba’s most solemn (note the child sovereign’s viscous yet proud gaze). Another interesting portrait is that of Caterina Barbarigo Sagred, a Venetian noblewoman who was portrayed several times by Rosalba (here she is seen dressed in a black robe under which the white lace of the petticoat can be glimpsed: she wears a pearl necklace, which she wears in the same way as the girl with the parrot we saw earlier, has a red bow badly knotted on her chest, and wears a tricorn, the typical Venetian headdress, which, however, is on her twenties and thus allows a glimpse of her thick hair). The woman is depicted with an almost provocative gaze, partly masked, however, by the sweetness of the young woman who, in the same way as the lady with the parrot, communicates great femininity and mischief.

|

| Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of Louis XV as Dauphin of France (1720-1721; pastel on paper, 50.5 x 38.5 cm; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of Caterina Sagredo Barbarigo (1735-1740; pastel on paper, 42 x 33 cm; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Rosalba Carriera, Lady with a Parrot (ca. 1730; pastel on paper, 60 x 50 cm; Chicago, Art Institute) |

Rosalba Carriera’s production consists almost entirely of works on pastel. Wide is the distance that separates this technique from oil painting. From a practical point of view, pastel painting guaranteed several advantages over oil painting: fewer tools were needed to prepare the painting (in fact, the colors were already ready for use: pastel is nothing but pure pigment held together by little binder, mainly oil or wax, and it was precisely this purity that made the final result very luminous). Again, pastel, since it did not have to dry like oil colors, also required less time to make the painting, a feature that, according to the mentality of the time, allowed pastel to be considered a suitable technique for women who thus had time to devote to household chores without getting too absorbed in painting. Also not to be underestimated were the advantages related to the fact that the material could be transported more easily than that required by oil painting, and costs were lower.

However, pastel also carried some disadvantages: given the extremely pure nature of pastel colors, paintings made with this technique were very fragile. Consequently, to ensure the durability of pastel paintings, fixatives had to be used with care, and over time there were many recipes for preparing substances that could protect pastel paintings from damage (it is well known that it is enough to barely touch a work made in pastel to damage it, if the colors have not been fixed). The fixatives themselves could be another disadvantage because if prepared poorly they could cause even more damage, altering the colors of the painting. Another disadvantage was that correcting a pastel painting was more difficult than correcting an oil painting. For all these reasons painters over time preferred to apply themselves to oil painting. Pastel was not, however, an invention of the eighteenth century: it seems that this technique had been invented in the fifteenth century by a French painter named Jean Perréal (Lyon, c. 1450 - Melun, after 1530), but it was in the eighteenth century that it became widely known, and much credit for this diffusion can be attributed precisely to Rosalba Carriera, who not only rediscovered this technique but brought it to the heights by creating compositions that had nothing to envy in comparison with oil paintings.

|

| Rosalba Carriera, life and major works of the lady of the pastel |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.