Of the entire oeuvre of Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 - Giverny, 1926), most of the general public, who perhaps also attend exhibitions onImpressionism, tends to know mainly the works of the 1870s and 1880s, those that more than others helped to define the poetics of Monet himself and of Impressionism as a whole. His early works, those closest to realist art, are also well known, as well as his experiments with light in the 1990s (those, to be clear, of Rouen Cathedral), just as famous are the Water Lilies, also located between the 1990s and the early twentieth century. The last Monet , on the other hand, is an often neglected subject, although public taste is certainly not to blame for this: exhibitions on the Impressionists have hardly delved into the twilight of Monet’s long career by devoting due attention to it, and only in recent times has this part of his production been put under the magnifying glass. This neglect is probably due to misconceptions about the eye disease that had struck him in 1912 and that did not allow him to perceive colors as before.

Having become nearly blind, in 1923, at the age of eighty-two, he underwent an operation that nevertheless did not allow him to recover the color vision that had enabled him to paint the founding masterpieces of Impressionism: his eyesight was in fact severely impaired, his perception of colors had profoundly changed, and Monet himself was said to be in pain. That did not stop working, however; Monet continued to paint until almost the last days of his life. The subjects were those dear to him: his garden at Giverny, the Japanese bridge, water lilies. But his production had undergone an abrupt change in the last ten years of his life.

It was from 1890 onward that Monet, a botany and gardening enthusiast, modeled his garden at Giverny, turning it into an inexhaustible source of inspiration, so much so that between 1900 and 1926 nearly three-quarters of his vast output, amounting to some four hundred and fifty canvases, is devoted to views of his garden and the celebrated water lilies. Water lilies, “water landscapes” as he called them, became almost an obsession for him, by his own admission. As early as 1890, Monet confessed to his friend Geffroy, “I have still been shooting things that are impossible to do: water with grass swaying at the bottom...it is an admirable thing to see, but to want to do it is the stuff of madness.” Years later, in 1907, he would reiterate, “These landscapes of water and reflections have become an obsession. They are beyond my strength as an old man, and yet I want to succeed in rendering what I feel. I have destroyed some-and I am starting them again. And I hope something will come out of so many efforts.” A visceral dedication to his artistic project.

His progressive loss of sight was the crucial factor in the transformation his landscapes would experience in the last years of his life. Indeed, the altered perception of colors prompted Monet to practice a more intuitive and less descriptive use of color: the artist resorted to the expedient of arranging the colors in tubes on the palette in a strict order to obviate the less sharp vision of the different hues. At this stage, scholar Emmanuelle Amiot-Saulnier has written, “his brushstrokes become more obvious and seem to vibrate to the rhythm of luminous sensations, rather than accurately restoring optical perception.” Ironically, this condition of near-blindness allowed him to “develop an ability to vibrate to the rhythm of light and in unison with the world,” transforming his defect into an artistic sublimation, until he came to embody “the image of the man who sees and perceives for the first time.”

The signs of this quest are already evident in the monumental series of Nymphéas destined for the Orangerie in Paris. Begun in 1914 and donated to the French state in 1918 to celebrate the Allied victory, these works were conceived to be exhibited in an environment that enveloped the viewer. This circular installation, a dream dating back to 1898, aimed to create an illusion of a whole without end or beginning. The artist provided himself with a vast studio of two hundred and sixty-six square meters in Giverny, illuminated by a zenithal window, which resembled an industrial structure and allowed him to work on gigantic canvases with movable easels. This choice of the monumental format, in which the landscape surrounding the basin gradually disappears to make room for the water lilies alone pushes the canvases toward a form of abstraction by itself. In the Water Lilies, there is no longer land or sky: attention spreads and spills everywhere, freeing the painter from perspective, in pursuit of a new fluidity that bordered onabstraction. However, in addition to the Water Lilies, there are other series from the later Monet that reveal, perhaps even more strongly, this tendency toward abstraction. The Weeping Willows, executed between 1918 and 1919, reflect Monet’s deep grief over personal loss and war. In these works, water, sky, clouds and flowers often disappear, giving way to the lone trunk and the undulating movement of the branches. Pronounced chiaroscuro and vibrant brushstrokes result in a deeply expressive rendering, where gesture and color gain increasing autonomy, moving away from realistic representation.

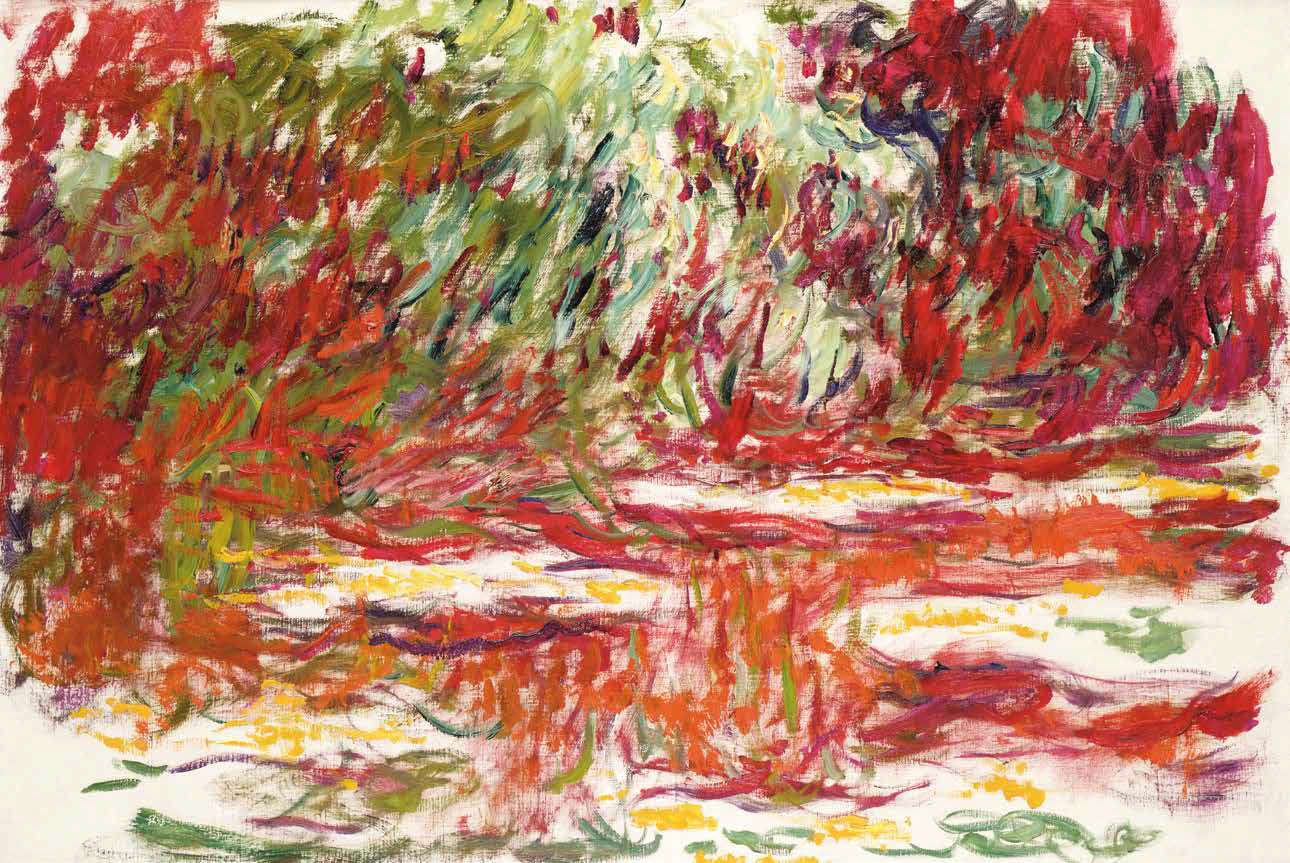

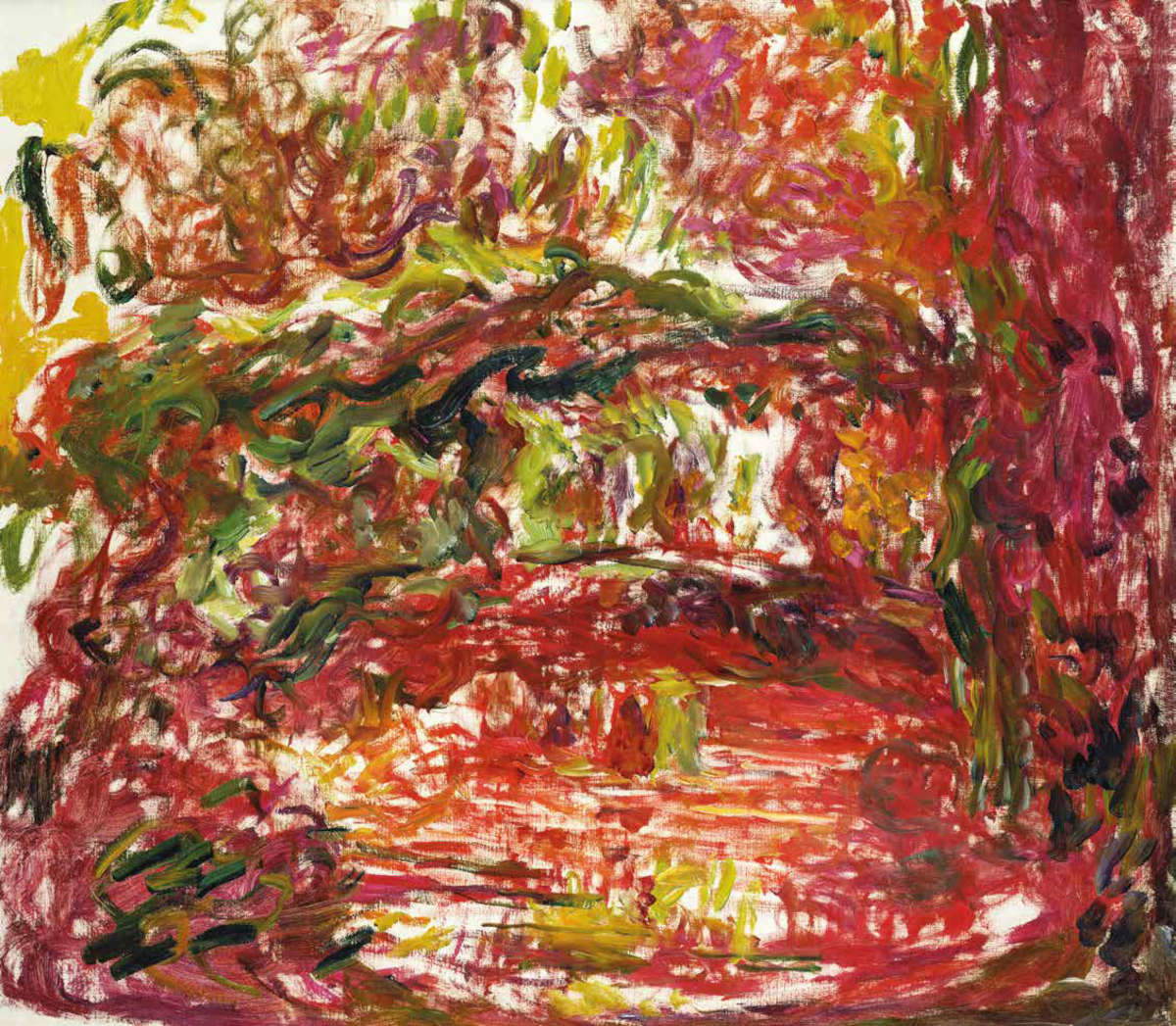

The Japanese Bridge series, although reflecting Monet’s admiration for masters such as Hokusai and Hiroshige, is also distinguished by its tendency toward abstraction. In works such as Japanese Bridge, circa 1918-1919, dense vegetation and small touches of color create a vortex that dissolves the structure of the bridge. Light, perceived by the artist’s ill eye, filters through “luminous windows,” as Géraldine Lefebvre called them, that mix whites and yellows with greens and blues, transforming the small bridge into an image that almost dissolves within that “extraordinarily dense vegetation.” In some of the last canvases of this series, especially the later ones, Monet plays with the uncovered white of the canvas, and the use of intense reds is an indication of the progress of cataracts and impaired vision. However, these canvases are among Monet’s most visionary, whether the artist set out to achieve this goal or not (the latter being the most likely). The point, however, is that in the immediate term he was not understood: in 1923, dealer Joseph Durand-Ruel, observing these last works, noted that Monet “could no longer see anything and was no longer aware of the colors.”

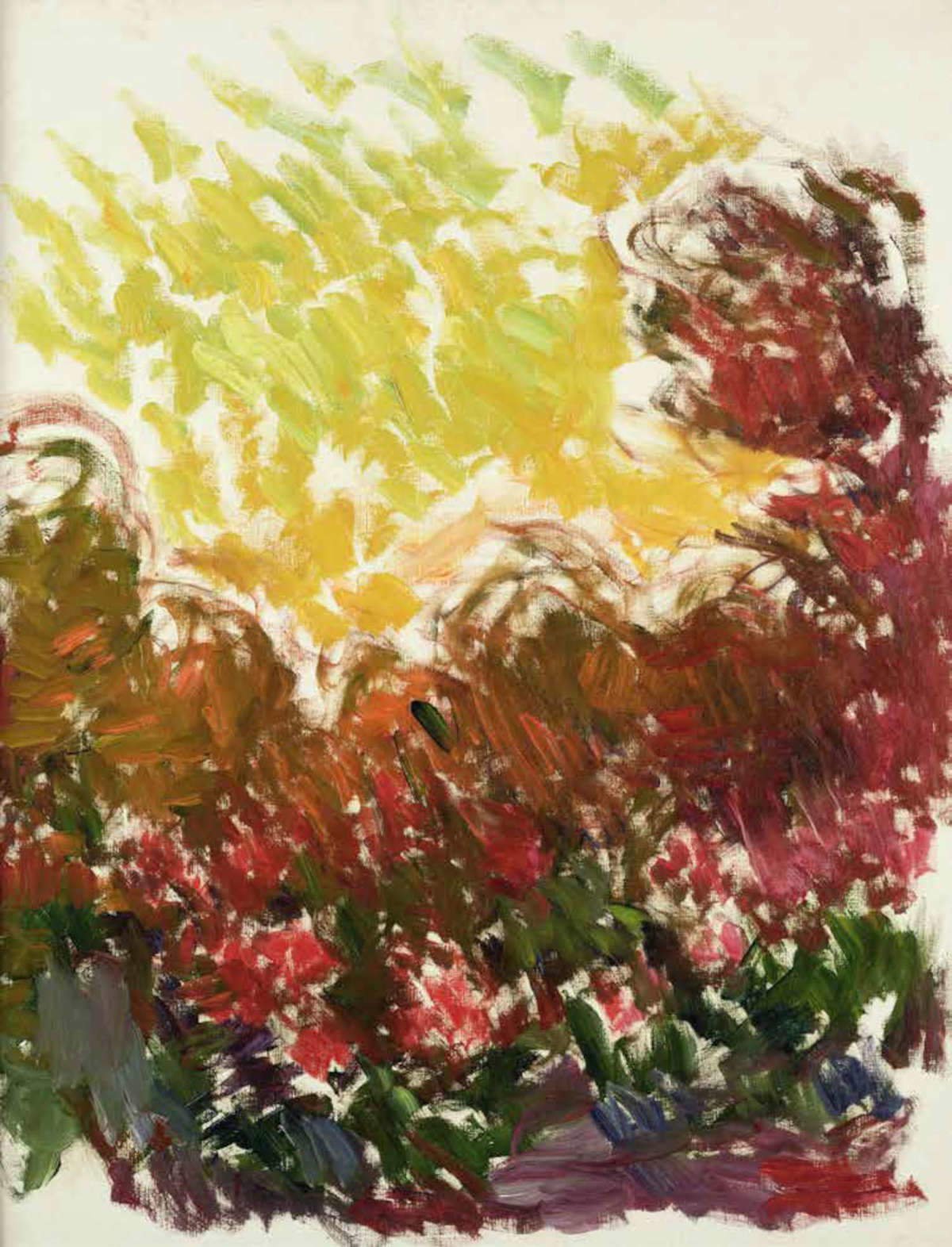

Some extraordinarily powerful works, such as the Avenue of Roses and Giverny Garden, which date from the early 1920s, show further evolution. In the Avenue of Roses, the iron arches of the arbor and the vegetation completely fill the space, reds and greens predominate, the brushstrokes overlapping with thick layers of impasto that create a completely disorienting image, which has almost no hold on reality except in the elements that suggest the structure of the objects Monet paints. We have left observation and have definitely entered the painter’s vision, we see things as Monet saw them, with his sick eyes. In the Garden of Giverny, Monet even goes so far as to eliminate the realistic details that were also still present in the paintings he made earlier, keeping, Lefebvre writes, only “broad chromatic masses: the greens, reds and yellows become signs of a lush nature.” These are almost entirely gestural works, works that have almost completely lost all connection with reality, works that achieve an unprecedentedlyrical abstraction . These works, which Monet considered so personal that he never exhibited during his lifetime, reveal the more intimate side of his work, and were a key source of inspiration for twentieth-century art.

Several of these works are now at the Musée Marmottan-Monet and were exhibited in good numbers in Padua, Italy, in the major Claude Monet exhibition of 2024, curated by Sylvie Carlier and Marianne Mathieu, an occasion where it was reiterated how these paintings of his anticipated the U.S. abstract expressionism of the 1950s, a thesis that was amply supported during an exhibition held in 2018 at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris(Nymphéas. L’abstraction américaine et le dernier Monet, curated by Cécile Debray). At the outset, it should be noted that the initial reception of these works was often critical. By the time the Water Lilies at the Orangerie, which were not even Monet’s most extreme works in this respect, were inaugurated in 1927, they appeared backward in an era that favored on the one hand a return to order and on the other a continuation of research devoted to geometric abstractions. Many critics rejected them. Even, in 1939, Lionello Venturi wrote that the "Nymphéas of the Orangerie“ were ”his most serious artistic error.“ Almost no one could appreciate these paintings, wrote art historian Laurence Bertand Dorléac, ”before 1945, without fearing the primacy of sensation over the precision of the subject, which is no longer a particular object, but its atmosphere, composed of a myriad of moving signs, a strange dynamic of life in slow motion, a dream machine. In other words, Monet had escaped the wanderings of the interwar period and the national ’return to order’ in France." However, his more abstract works were posthumously successful: “they were rediscovered after World War II [...]. By 1914, the obsessive desire to ’construct’ and ’represent’ was equal to the anxiety of seeing everything heading toward collapse, dissolution, and destruction in the chaos of history. Any art that approached this very real danger could only be condemned. From 1945 onward, artists themselves responded to this long dark trend by putting gesture, the body, chance, the informal, matter, stain, poetry, imperfection, fragility, subjectivity and the physical experience of art back at the center of their operations as so many signs of liberation. In this new context, all that was so displeasing to Monet could be properly valued in the context of the freedom of a work made without instructions.”

Only in the 1950s, then, were these works considered masterpieces. Clement Greenberg, referring to the Water Lilies (in which he recognized a pivotal work of the 20th century) in 1957 described the works of the last Monet as “a culmination of revolutionary art,” noting that Monet could be considered “an ’experimenter’ as daring as Cézanne.” His "eye obsessed with an absolutely naive form of exactitude, finally reacted by demanding textures of color that it was possible to master on canvas only by invoking the autonomous laws of the material. In other words, nature served as a springboard to an almost abstract art." Monet’s late works, then, were not only the testament of a master of Impressionism, but also the prelude to new forms of art. Through the intensity of his vision, technical audacity and pursuit of pure sensation, Monet laid the foundation for a pictorial language that, while rooted in nature, transcended representation to approach a lyrical abstraction that would somehow condition, albeit silently, the course of modern art.

The real “awakening” of interest in the last Monet came about mainly through an outside gaze, that of American artists and critics. The reopening of the rooms of the Orangerie in 1952, after damage sustained during the liberation of Paris, was a crucial moment. André Masson, who had returned from New York, described the Orangerie as the “Sistine Chapel of Impressionism,” stimulating the interest of abstract expressionists. Paul Facchetti, organizer of Pollock’s first exhibition in Paris in 1952, testified how the Orangerie had become a kind of pilgrimage site for American artists.

It was in this context that figures such as Alfred H. Barr Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, began to see in Monet a bridge between the naturalism of early Impressionism and contemporary abstraction. In 1955, MoMA acquired a large panel of the Water Lilies, a significant choice that Barr justified by noting how the work responded to the “renewed interest of young painters here and elsewhere in the artist’s late works.” American critics, particularly Clement Greenberg, initially skeptical of Monet’s late works because of their lack of three-dimensional structure and tendency to reduce painting to mere color texture , very soon revised their position. The emergence ofAbstract Expressionism, with artists such as Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, allowed a new interpretive framework to emerge around Monet’s works. These artists, with their works that had no beginning, middle or end, shared with the last Monet the idea of an extended, non-hierarchical pictorial surface. Greenberg himself recognized in 1955 the “paradox” whereby art such as that of the last Monet, “which in its time satisfied a mundane taste and still made most of the avant-garde quiver, suddenly finds itself highlighted and considered in some respects more advanced than Cubism.” Artists such as Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell and Philip Guston were considered Monet’s heirs, and although Guston denied direct influence, they were credited with a visual sensibility that inevitably linked them to the Water Lilies. Sam Francis, among others, confessed that Giverny’s works of the later Monet left a lasting impression on him: “They were wonderful, because they were so free, almost like the paintings of a blind man.” It was a sensibility that was not denied even by Ellsworth Kelly, who openly declared that he had received such “influence” from Monet that he had inspired him with “the idea of being able to make a painting with only one color.” Kelly was attracted to the idea of “painting the size of walls.”

The impact of the last Monet was obviously felt on this side of the Atlantic Ocean as well, and particularly in Italy, where his research was a starting point for the work of several Italian artists in the 1950s. The appeal to Monet united artists from different paths: those who came from the most rigorous abstraction, those from the borderline between figurative and abstract, those from informal or autonomous experiences. Fabrizio D’Amico, in one of his essays, recognized in several Italian artists linked to research on informal art the suggestions drawn from Monet: artists such as Ennio Morlotti, Marco Gastini, Antonio Corpora, Renato Birolli, Pompilio Mandelli, Tancredi, and even up to the 1980s and 1990s with artists such as Mario Schifano (who, moreover, directly took up the Water Lilies) and Davide Benati. In this interweaving of experiences and sensibilities, Monet’s legacy proved to be an inexhaustible source of inspiration, capable of crossing generations and different languages.

Monet himself, as mentioned, did not consider himself an abstract artist; his research was always anchored in transcribing the impressions of nature, although this would lead him, in his later years, given his physical problems, to the visionary phantasmagoria that animates his late works. Works that foreshadowed the experiences of modern art, with a painting that was not only the pinnacle of his Impressionist research, but in fact stood as a catalyst for the avant-gardes of the future, capable of becoming a source of inspiration decades later, as the legacy of an artist who, while keeping faithful to nature, pushed the boundaries of painting to the point of touching the beauty of the formless and pure sensation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.