The one that Palazzo Reale in Milan is dedicating to Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (Valencia, 1863 - Cercedilla, 1923), a great Spanish painter who lived between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, famous above all for his scenes of marine life and for his beaches bathed in extraordinary light and crystalline reflections, aims to be the first monographic exhibition in Italy that covers the artist’s entire activity and all the themes addressed in his production through sixty masterful works and five thematic sections. In fact, already in 2012 Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara had dedicated an exhibition to Sorolla, entitled Sorolla. Gardens of Light, but the curators Tomàs Llorens, Blanca Pons-Sorolla, María López Fernández and Boye Llorens had focused on the production of his full maturity and in particular on the works born from his fascination with the theme of the garden and his encounter with Andalusia, which would later result in the creation of his artist’s garden created in his new home in Madrid, the current Museo Sorolla; the same fascination that had also led the master of French Impressionism Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 - Giverny, 1926) to create at his home in Giverny his lush and poetic garden that still attracts thousands of visitors from all over the world.

Joaquín Sorolla. Painter of Light, this is the title of the Milan exhibition that can be visited until June 26, 2022, which again emphasizes the preponderant role of light in Sorolla’s painting; in her catalog essay Consuelo Luca de Tena, one of the curators, states: “It is curious that Sorolla became known as ’the painter of light,’ since, in his day, an interest in light was a common denominator among all painters, although he was probably the only one to accept the challenge posed by the violent light of the Spanish Levant with the sun at its peak and in the middle of summer... Monet himself would say of the Valencian that he was a reveler in light.” Curated by Micol Forti and Consuelo Luca de Tena in collaboration with Blanca Plons-Sorolla, great-granddaughter of the famous artist, the monographic exhibition has among its reasons, presented to visitors in an introductory panel, that of recounting an artistic experience "in which the study of light represents the main path of renewal toward the elaboration of an immediate, spontaneous and refined pictorial language," which the public can clearly see already in the first room that welcomes the extraordinary masterpiece conserved at the International Gallery of Modern Art at Ca’ Pesaro in Venice, Sewing the Sail, and then continuing in Triste eredità! and in the portrait of his father-in-law Antonio García on the beach, but in particular in the sections devoted to the sea, a great constant in his artistic production as a good Valencian born and raised by the sea, and to gardens, in which he has a way of pursuing his almost obsessive research on light that began in the waves of the sea and here is instead filtered through vegetation or reflected in pools that are part of the architecture of the outdoor space.

Through its five thematic sections, the exhibition aims to trace the painter’s artistic evolution, from social themes to portraits, from sea views to gardens to the long and ambitious Visions of Spain project commissioned by theHispanic Society of America. Visiting the exhibition at the Royal Palace, the public enters Sorolla’s universe, from his beginnings to the achievement of great success that would take him to the New York metropolis. The exhibition begins with theSelf-Portrait of 1900 in which the artist depicts himself in a moment of pause from his activity: he is in his studio surrounded by his drawings and wearing his open white work coat, under which a gray suit can be seen. It is a portrait in which he exhibits his identity as a painter, he who in his life never wanted to be anything but a painter, as he replied to a journalist during an interview in his old age: He made the self-portrait in the same year that he won the Grand Prix at theUniversal Exhibition in Paris , and so it is a painting in which he shows himself proud of his important achievement, but before he reached that recognition years passed and he made several works that he sent to major national and international exhibitions in an attempt to establish himself as an artist.

Social themes were particularly prevalent in these contexts, and so in the 1890s Sorolla began to execute paintings on the truest and crudest aspects of contemporary Spain; influenced by his friendship with Vicente Blasco Ibañez, author of novels about the miserable conditions of Valencian fishermen and peasants, he took to depicting scenes set indoors and en plein air on the themes of prostitution, poverty, and disability. Examples of this in the exhibition are Tratta delle bianche, which depicts four young prostitutes together with their procuress as they fell asleep exhausted inside a third-class train carriage: it was in fact customary in the Spain of the time to move very young prostitutes from one workhouse to another via the railroad, or Sad Inheritance which recounts the widespread idea that the children of vice and alcoholism were born with deformities and disabilities; it was the latter painting that won him the Grand Prix at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. Both are emotionally charged works, but the marked change can be seen in works such as Return from Fishing, presented at the Salon de la Societé des Artistes Français, awarded a first-class medal and purchased by the State for the Palais du Luxembourg, and in the monumental Sewing the Sail: paintings in which Sorolla depicts scenes of life from the humble work of fishermen, without any kind of denunciation and characterized by a strong naturalness of the everyday, as well as by an extraordinary use of light that is reflected on the bodies, on the water and on the large blank canvas that the fishermen’s wives are mending on a brightly lit patio in total harmony.

Sorolla’s attention to light is certainly influenced byImpressionism, which he knew in Paris and with which he shared various aspects, such as painting from life, the application of colors by juxtaposition without mixing them, and the desire to capture light at different times of the day in order to transfer it to the canvas, particularly in the seascapes where the surface of the water offered the right opportunity for the study of reflections and iridescent colors, which also expanded on the bodies of festive and joyful children bathed in water. Unlike the Impressionists, however, Sorolla added drawing (quick preparatory sketches without a defined outline enclosing the figure) and the corporeity given by the movement of the figure itself, of which the Swedish painter Anders Zorn was a master; of Velázquez, whose art he was fascinated by during his visit to the Prado Museum, he admired instead the fusion between the figure and the surrounding space in an atmosphere that unifies the image. In line with these assumptions, he produced his famous maritime scenes depicting the daily life of fishermen, as in Return from Fishing and Napping in a Boat, and especially the childish games of children running on sunny beaches, jumping and swimming in the water, playing with little boats, and frolicking on the shore, expressing all their vivacity and spontaneity. On display expressed in works such as Valencia Beach in the Morning, Idyll by the Sea, The Little Boat, Afternoon on Valencia Beach.

In addition to the Valencian beaches, Sorolla also has occasion to paint on the beaches of Biarritz, on the northwest coast of France, where he goes to rest with his wife and children. A destination frequented by high society and more cosmopolitan than Valencia, Biarritz gives the artist an opportunity to deal with a cooler luminosity and a more variable climate, as well as with leisure scenes of elegant society dressed in light white dresses moved by the breeze and illuminated by the blinding sunlight. Examples of this are on view in the exhibition On the Beach, Biarritz and On the Beach in Biarritz, but the protagonists of famous paintings set on these beaches are the women of the family: his wife Clotilde in the very famous Snapshot, Biarritz and the eldest daughter Maria in Mary on the Beach in Biarritz or Control Light. Missing from the roll call, however, is the famous Walk by the Sea, preserved at the Sorolla Museum.

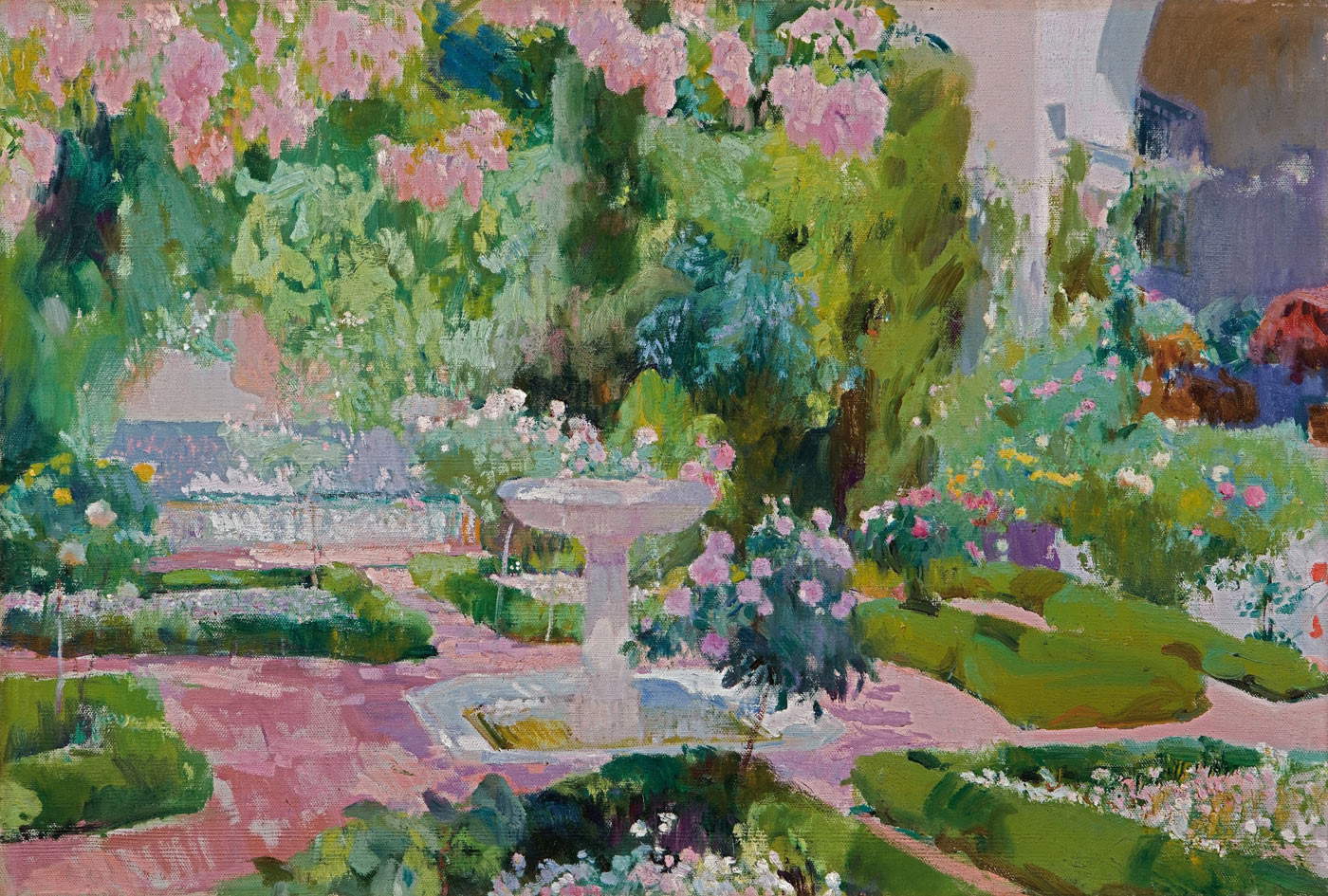

The attention to reflections and light is a cue for paintings set in gardens that Sorolla began to make beginning in 1907 and to which an entire section is devoted. These are works that take the visitor to scenes en plein air in theAlcázar in Seville, theAlhambra in Granada, and La Granja de San Ildefonso in Segovia, where Sorolla had obtained permission to portray Spanish rulers Alfonso XIII and his wife Victoria. Also made with quick, decisive brushstrokes, these paintings show the happy combination of vegetation and light, creating splendid reflections thanks to the architectural fountains that are often at the center of the composition. And so it is possible to admire The Basin of the Alcázar in Seville or Courtyard of the Alberca, Granada, but his great passion for gardens later resulted in the creation of the one surrounding his new Madrid home built in 1910, where he spent his last years as a painter, between 1918 and 1920, immersing himself among the plants and flowers and the affection of his family. Visible here is the Garden of Casa Sorolla played on shades of green and pink with a fountain in the center. Significant and evocative, on the other hand, is the painting Garden of Casa Sorolla with Empty Chair, which becomes almost a farewell to the artist: in a shaded corner of the courtyard the wicker chair on which the painter sat is empty, probably depicted shortly before the stroke that struck him and would force him to abandon painting for the rest of his days. For landscape painting he was influenced by the painter Aureliano de Beruete, who was linked to the Institución Libre de Enseñanza whose principle of knowledge of nature as a fundamental aspect of education and the pure representation of landscape as a vindication of themost authentic Hispanicism he shared. Chapter apart among the landscapes depicted by Sorolla are the gouache views executed in New York City in 1911 from the window of the hotel where he was staying: top-down views depicting 59th Street, Fifth Avenue, and the Marathon; scenes of the bustling urban landscape of the Big Apple that present the incessant flow of cars, cabs, and people and the reflections of headlights on the wet asphalt.

He had already been to New York for his major exhibition in 1909, which was a real success, commissioned by the American patron Archer M. Huntington for his newly created institution, theHispanic Society of Art. Huntington was thunderstruck by Sorolla’s painting when he visited his major exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London the year before. In Britain’s capital, the Valencian painter, unable to paint outdoors because of the weather, spent his time visiting the city’s museums and monuments, and in particular got to see the Parthenon marbles , which fascinated him to such an extent that he introduced the Greco-Roman model expressed in several of his works through women of imposing, monumental and statuesque dimensions and draperies reminiscent of Greek sculpture. Exemplifying this is the painting entitled The Pink Robe, done life-size and considered by the artist himself to be “one of the best he ever made.” It was painted in Valencia in the summer of 1916 (it is in fact placed at the end of the exhibition itinerary even though it is a painting “on the beach”), in a break from the complex undertaking of the Visions of Spain, and depicts in an intimate atmosphere two women after bathing caught in a cabin in which sunlight filters through the reeds and into which a light breeze enters as can be seen from the white curtain that appears to the left of the composition; the younger, buxom woman’s pink robe clings sensuously to her wet body , making her a modern Venus.

Monumental dimensions are also found in Valencian Women Fishermen, where three life-size female figures occupy the entire canvas with their imposing presence.

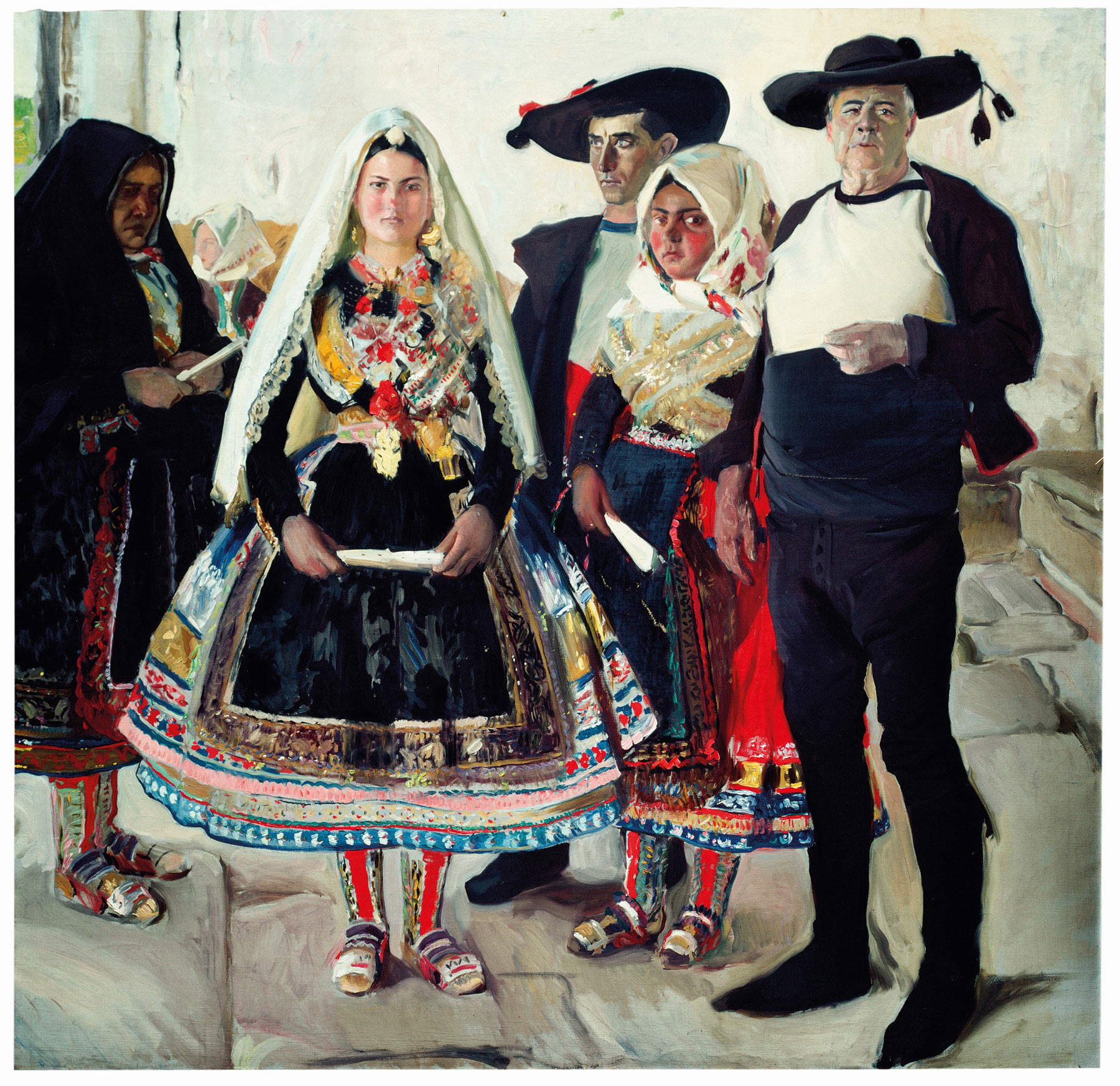

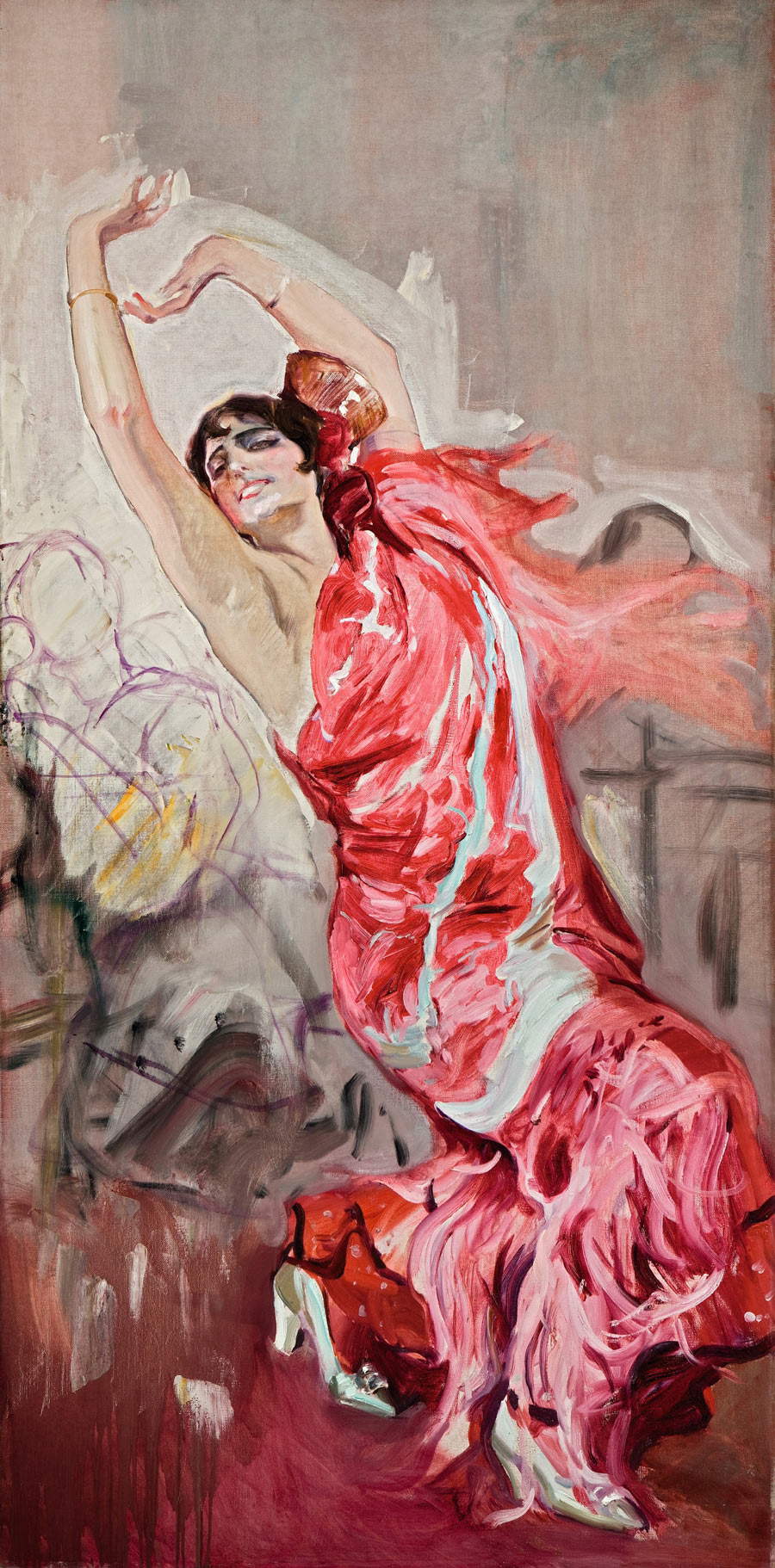

Finally, mention has already been made of the extensive series Visions of Spain commissioned from Sorolla in 1912 by patron Huntington for the decoration of the library of the Hispanic Society of Art, to which the Palazzo Reale exhibition devotes the last major section. It was along and arduous undertaking that occupied seven years of the artist’s work and forced him to travel throughout Spain in all weathers. The project involved depicting an overview of the various Spanish regions that Sorolla would visit from life to describe their landscapes and characteristic types, for a total of sixteen scenes. Presented in the exhibition are the Tipos of El Roncal dressed in the typical clothes of the local fashion, the Tipos manchegos, the Lagarteran Bride, Two Sevillian Women, and the brilliant Flamenco Dancer wearing a sparkling bright pink dress.

When the venture was over, Sorolla moved to Majorca, where he had the opportunity to return to confront sunsets over the water, rich in contrasts created by backlighting, as in Clotilde at the Cove of San Vicente, Majorca, where the colors of the sky are reflected on the quiet surface of the water in broad patches of color. Though as soon as possible, even during the years of the cycle of canvases for the Hispanic Society, he returned to his beloved Valencian beaches to make, for example, the aforementioned Veste rosa (Pink Dress ) or After Bathing painted under the blazing midday sun.

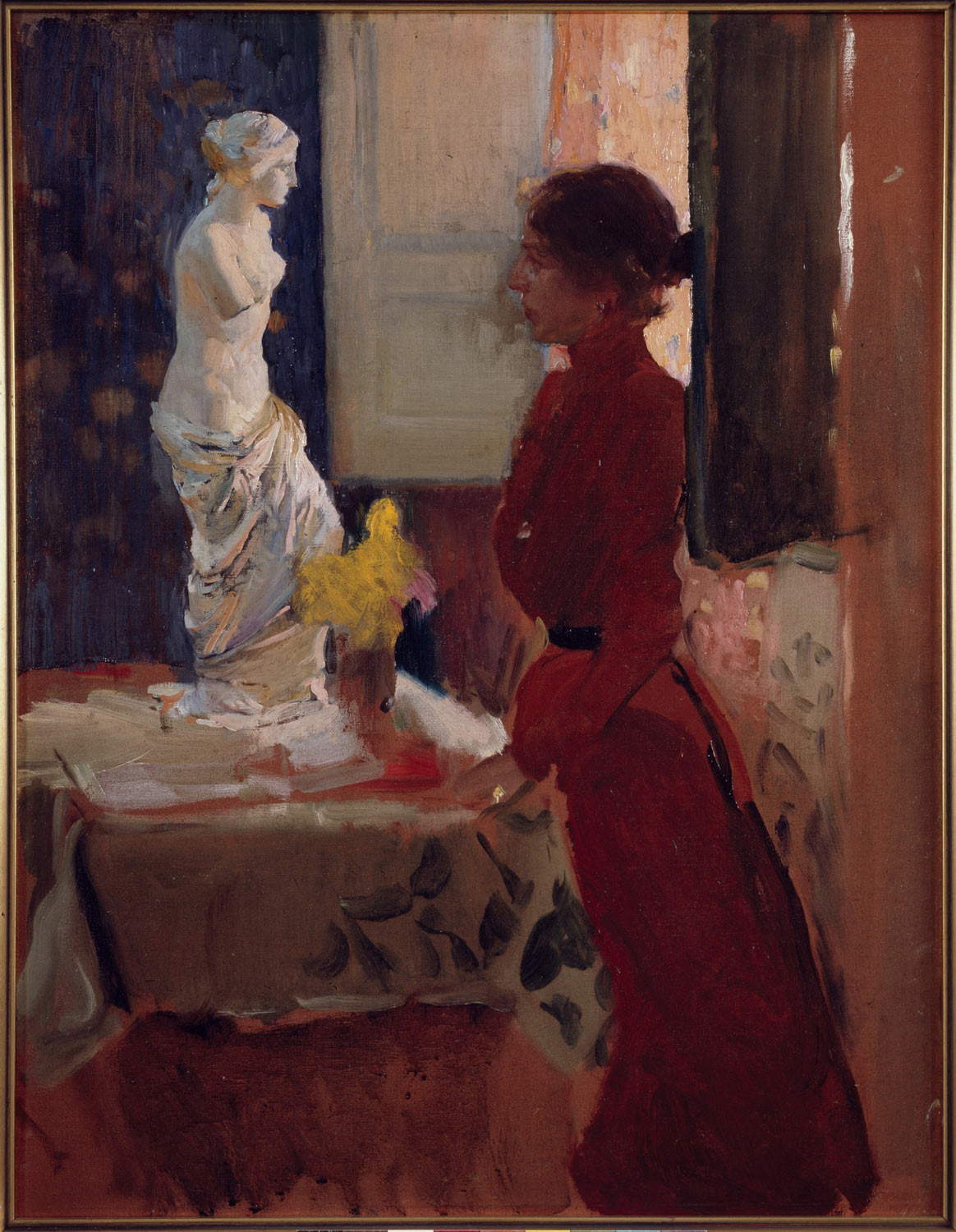

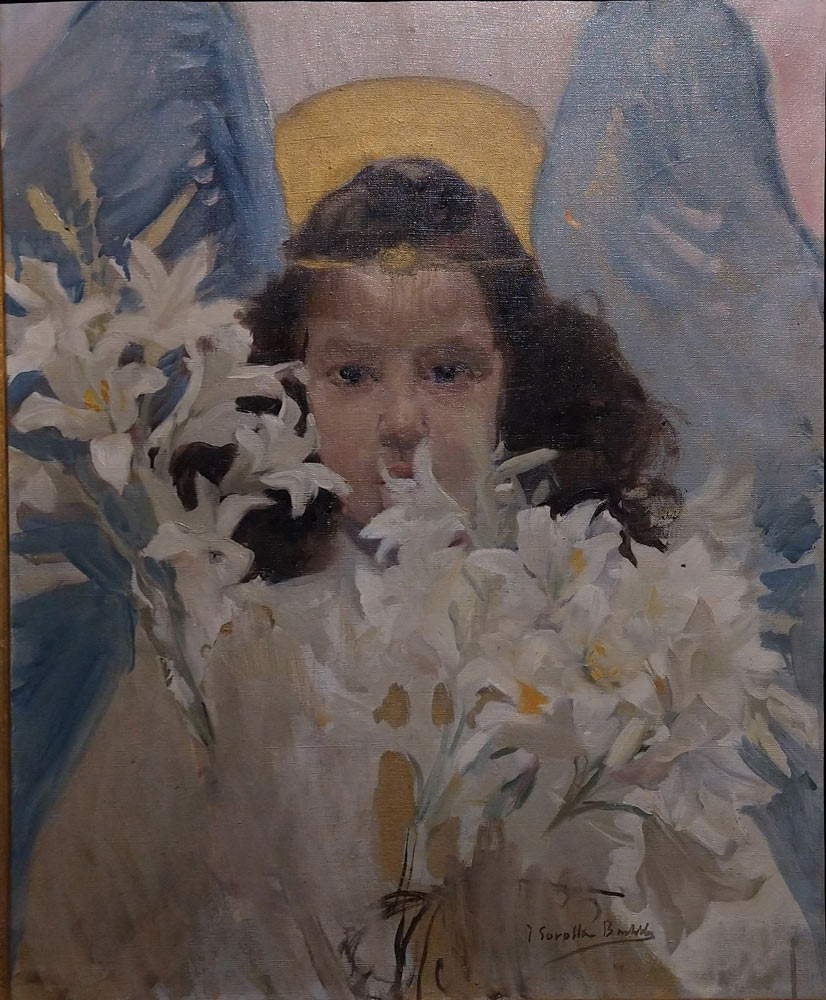

What becomes very clear to the visitor throughout the exhibition is the strong emotional bond with his family, documented through the presence of many paintings featuring his beloved wife Clotilde and their three children, especially their eldest daughter Maria. He devoted the greatest number of portraits to them (a specific section is devoted to this theme among the social and beach-themed paintings), introducing them to that magnificent world of light and reflections characteristic of the painter. They are quick snapshots of everyday life in which he leaves the faces almost undefined, as in My Wife and My Children, in Under the Tent, Zarautz Beach, or in The Siesta where Clotilde, his two daughters and cousin are lying on the grass in sweet idleness; portraits of his wife Clotilde, such as the well-known Clotilde and the Venus de Milo, Clotilde with a black mantilla, orportraits of his eldest daughter Maria, depicted in Maria with Lilies while still a child, Maria convalescing as a 17-year-old when she fell ill at the end of 1906 of tuberculosis and in the hope of aiding her recovery the family moved to the mountain of El Pardo, Maria on the beach of Biarritz or Controluce, Maria in the gardens of La Granja depicted in the months just after her convalescence in the company of a little girl daughter of the critic Leonard Williams in front of a pool of water in which the foliage of the plants around is reflected. Also worth mentioning is the celebrated luminous portrait of his father-in-law Antonio Garc&ia cute;a, who introduced him to the art of photography, as well as portraits to sculptor Paolo Trubetzkoy, American jewelry designer Louis Comfort Tiffany, and Nobel laureate in literature Juan Ramón Jiménez. Photography plays an important role for the artist: his painting can be likened to the language of photography, and his collection preserved at Casa Sorolla testifies to a man who is very familiar with the camera and is also at ease in front of the lens. The famous painting Snapshot, Biarritz depicts precisely Clotilde, dressed in a white dress moved by the wind, sitting on the seashore holding a small Kodak that was launched on the market in 1888.

What, on the other hand, in my opinion is not perceived by the public, even though it is presented as one of the reasons for the exhibition, is the painter’s connection with Italy: in fact, it is stated that the exhibition is an opportunity to “reknit the threads between the master of light and Italy,” but perhaps it would have been useful to devote a special section to this theme. Indeed, the painter had ties with Italy from an early age. In 1884 the Provincial Council of Valencia awarded Sorolla a three-year scholarship to stay in Rome from the following year, visited Venice, Pisa, Florence and Naples where he made numerous sketches, spent some time in Assisi with his wife to retire after the disappointment of one of his paintings that did not receive the result he had hoped for at the National Fine Arts Exhibition in Madrid, entitled Seppellimento di Cristo, and in the Umbrian city he was able to portray local subjects and characters against backgrounds of olive and almond trees: “It was the beginning of the right path, the path from which I no longer strayed even for a moment,” he declared. He also participated in the Venice Biennials, from the first edition in 1895 until the sixth in 1905, then again in 1914 and post mortem with a retrospective in 1926, and he also took part in the International Exhibition in Rome in 1911.

Joaquín Sorolla. Painter of Light is a tribute that Palazzo Reale in Milan wanted to pay towards a great master of light, among sunny beaches, gardens with a thousand reflections and family portraits. The public has the opportunity to get to know, through a pleasant and overall well-divided layout in its sections, apart from a few gaps mentioned above, an artist who is not as well known to most as Monet might be, but whose roots are in Impressionism and en plein air painting. In addition, most of the works on display come from the Sorolla Museum: thus we have the opportunity to see works housed in the painter’s last home that would only be visible by going to Spain. Accompanying the exhibition is a catalog with essays by the curators and other contributions on the Spain of the time from a historical and literary perspective and on Sorolla’s connection with photography. The volume also includes many shots depicting the compositional scenes from life that the painter then imprinted on canvas: from the photograph to the painting; an interesting and uncommon aspect to find. So a valuable popularizing exhibition for anyone who wants to learn about one of the most important painters of Spain at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who managed to achieve international success, so much so that he was acclaimed at the time as the world’s greatest living painter.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.