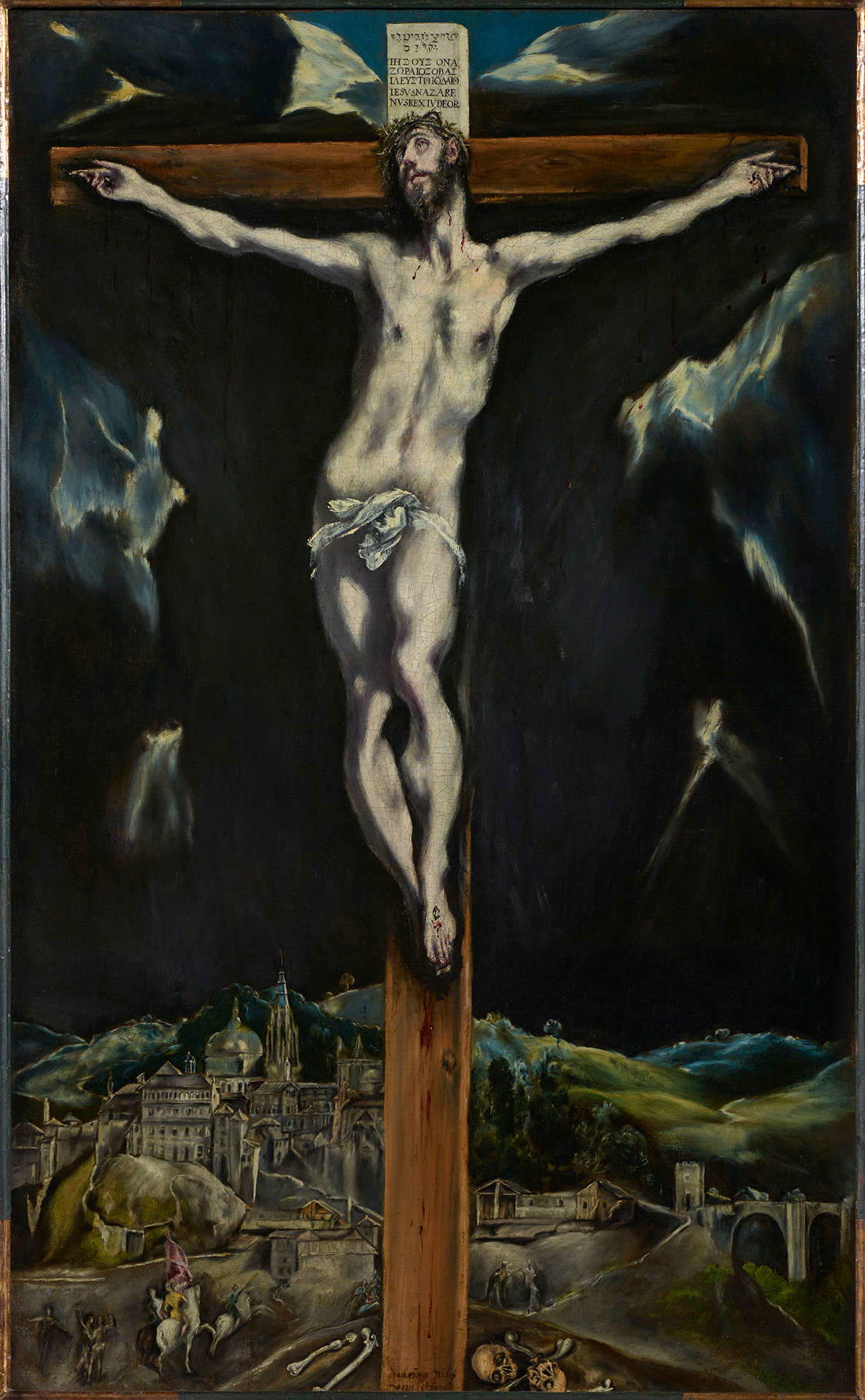

Scipione, who was the most tormented, poetic and passionate painter of the Roman School of the 1930s, signed one of the most intense pages of criticism on El Greco ever written. Scipione can be reproached for a lack of originality, since he wrote about El Greco what everyone thought and we all think today, and he can be reproached for having written almost on impulse, but it cannot be said that he did not feel deep down what he was writing, speaking about an artist who had preceded him by three hundred years: “For us El Greco is a visionary, with his painting he upsets minds, churches are populated with religious nightmares, he lifts up images and, transfiguring them, bringing them to an unreal plane, confusing the two elements, painting in the picture everything presents and with the same intensity. His figures are ghosts concreted with a terrible tactile reality; his figures are thin meshes because they do not end. The intangible beauty of the divine figures deforms, corrupts, to warn people.” El Greco is painter who has consumed all possible adjectives. Each of his works is like a hallucination. Every painting a journey. And every exhibition, therefore, becomes an event. El Greco is one of those artists of whom it is difficult to get tired, and when there is an exhibition about him usually one tends to indulge in a positive judgment, because one is enraptured by his swirls, his unreal colors, the spectres that populate his daring compositions.

Juan Antonio García Castro and Palma Martínez-Burgos García, curators of the exhibition El Greco. A Painter in the Labyrinth, on view until Feb. 11, 2024 in Milan, in the halls of the Royal Palace. El Greco is a captivating painter, and they needed an exhibition that would captivate, a scenic exhibition, an exhibition that would stun the audience (right from the introduction, one might malign, with the full reproductions of the institutional greetings in the catalog placed on the opening panels). All it takes is to gather a good and representative number of works, and to arrange around the pieces an engaging arrangement such as the one designed by Corrado Anselmi, compelling if a little tortuous, and the exhibition creates itself. The rest seems almost superfluous: the fact that there are no substantial novelties, other than a reinterpretation of the Italian models with which El Greco had to measure himself, and then the comparisons that are sometimes a bit drawn, the unexciting paneling, the too weak theme (the “labyrinth” of the title that would like to be an allegory of the vicissitudes of his life as well as a symbolic reference to the complexity of his painting, and of course all too obvious reference to the Cretan origins of Doménikos Theotokópoulos, known as “El Greco,” with Spanish article and Italian nickname as if to sum up the two lands that welcomed him). The project, in short, is not the best. But the curators have managed to assemble a nucleus of works of the highest level, in quantity and quality: anyone in the world who wants to delve into El Greco should perhaps even go to Milan rather than Toledo until February, since Toledo’s main works are on their way to the Royal Palace. And copious, too, is the selection from Italian museums: practically everything of El Greco’s that is preserved in our museums is now on Lombard soil, on loan to the Milan exhibition.

There have been, in the past, other exhibitions on El Greco on Italian soil. The last one not more than eight years ago, at the Casa dei Carraresi in Treviso: an exhibition curated by Lionello Puppi centered on El Greco’s “Italian” years, the period that Theotokópoulos spent between Venice and Rome, between 1567 and 1576. Further back in 1999, there had been a monographic exhibition at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, a major traveling exhibition that was the result of a collaboration between Italy, Spain and Greece (the first stop had been at the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, the second in Rome and the third at the National Picture Gallery in Athens, all curated by José Álvarez Lopera, María del Mar Borobia, Nicos Hadjinicolau and Claudia Terenzi), a project that made it possible to get to know the Greek painter’s entire career through many of his best-known masterpieces, through an itinerary composed of 78 works, as opposed to the 54 in the Palazzo Reale exhibition. And the main reason for visiting the Milan exhibition is precisely the chance to see so many of El Greco’s works brought together in one place, almost a quarter of a century since it last happened in Italy.

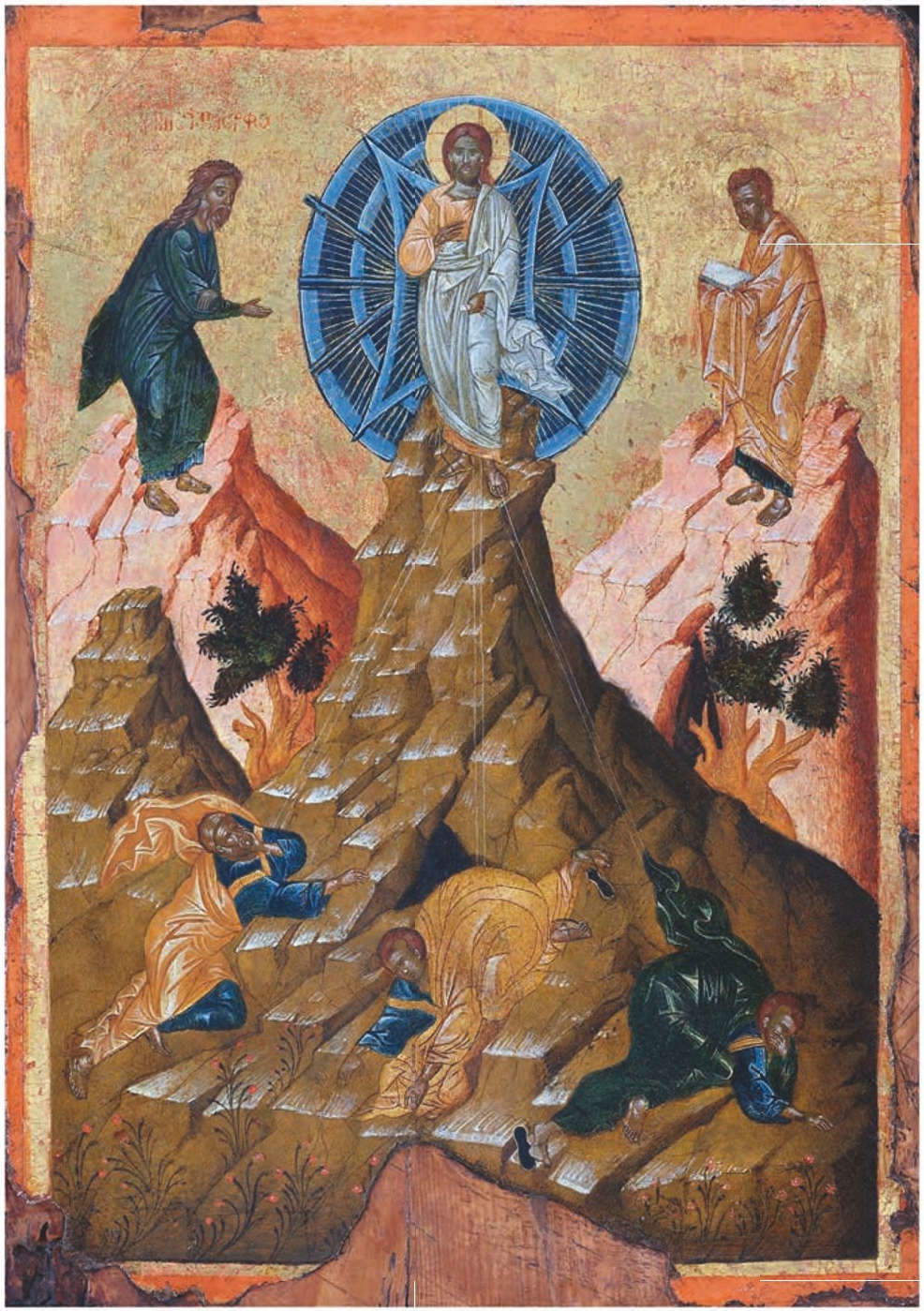

The opening of the exhibition introduces us to a young Doménikos Theotokópoulos who leaves his native island and lands in Venice, where he begins to forget his own training in order to paint, he who had trained among Orthodox icons, in the Western style: two Cretan icons by unknown authors recall the Dormitio from the church of Ermopolis on the island of Syros, a rare work from El Greco’s “Greek” period, discovered in 1983 and unfortunately absent from the exhibition (it is, however, evoked by a post-Byzantine Dormition from the early of the sixteenth century), and accompany the portable altarpiece from Modena, the first “luxury” loan of the Milanese exhibition, and a fundamental work in El Greco’s career since it is the first painting in which the abandonment of the entire Cretan substratum (the “Greek manner,” in essence) in the direction of Venetian painting is appreciated. In fact, the lagoon was El Greco’s first stop in Italy: he arrived in Venice in 1567 and immediately took to looking at the works of the great Venetians, especially Tintoretto, who helped from the very beginning to orient his painting. The Modena triptych, signed “Cheir Domenikou,” or “by Domenico’s hand,” is an early example of this. It is the spectacle of El Greco contained in just thirty-seven centimeters: theAllegory of the Coronation of the Knight that can be admired in the central compartment of the altarpiece is already an impetuous vision, with the angels clinging to the beams of light coming from heaven, the hellish monster at the bottom, Cirsto rising victorious over death and crowning the knight kneeling before him, a symbol of the miles Christi, the “Christian soldier” fighting against the forces of evil. Less rapacious, but already presaging later developments in El Greco’s art, is the scene with theAnnunciation that is seen (badly, because in the exhibition the triptych is tilted, perhaps too much so) on the back side.

In the next room the visitor in fact follows El Greco as he arrives in Venice: the small tablet with the Baptism of Christ from the Historical Museum of Crete in Heraklion, and the large Annunciation from the Julio Muñoz Ramonet Foundation in Barcelona, set against its counterpart work in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, recall the related scenes from the Modena altarpiece, revealing even more Western models. The Baptism of Christ is described in the catalog by José Redondo Cuesta, with some effectiveness, as the “first artistic ’vagito’ of a painter neophyte to Western art - albeit already in his thirties - immersed in the complex apprenticeship of the new artistic code of the Renaissance.” Doménikos Theotokópoulos, as an acquired Venetian we might say, paints in the Venetian manner: drawing is not yet in his chords, the composition is regulated by a color that is already in almost opalescent hues, enlivened by dazzling strokes of light, especially on the draperies, which look almost like chrome metal. In theAnnunciation, the model for the composition is Tintoretto, while the color is Titianesque, but the iridescences of the draperies, constant in this phase of El Greco’s art, look instead to Veronese. We find ourselves before a painter who has not yet fully developed his compositional autonomy and thus prefers to follow the lesson of the great masters of the lagoon, albeit trying to experiment and contaminate his points of reference, and despite the fact that this work was painted when the artist had already moved to Rome (indeed: they can be dated to shortly before his final move to Spain). We can reasonably assume that the artist had arrived in Rome in 1570, since a letter from that year by the greatest greatest miniaturist of the time, the Croatian Giulio Clovio, in which Cardinal Alessandro Farnese is asked for help in hosting a “young Candiotto disciple of Titiano” who had just arrived in the Urbe (in the catalog, moreover, a substantial essay by Giulio Zavatta and Alessandra Bigi Iotti reconstructs El Greco’s presence in Rome and his relations with the Farnese family).

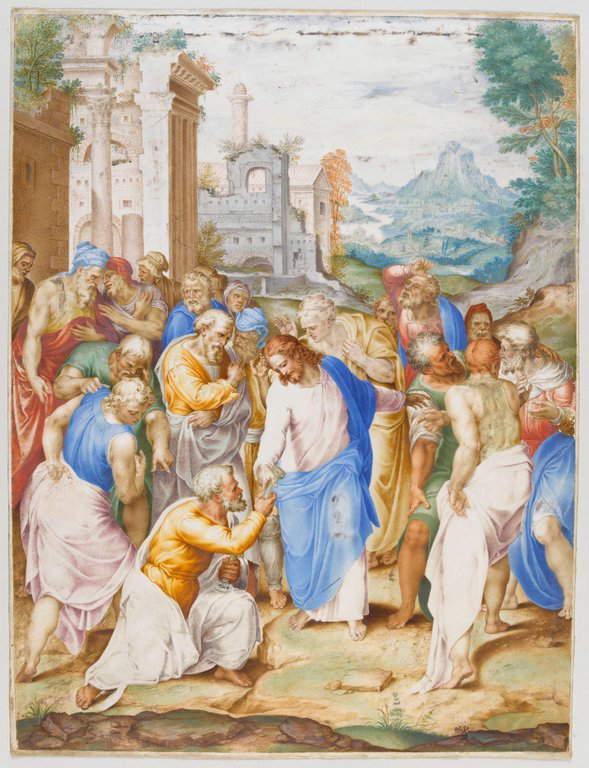

The next section is all about the “Italian” Doménikos Theotokópoulos and is all based on comparisons between El Greco’s works and those of his models. It begins with the small Last Supper from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna (the only known work with this subject by the Cretan painter, in a format that is, moreover, decidedly unusual for such an iconographic subject), which is displayed together with a work from Tintoretto’s workshop: the comparison makes it possible to note the points in common (the setting of the composition with the central table and the figures arranged around it, the gestures of certain characters, such as that of the apostle who snaps from his stool in amazement as he holds onto the table, the very shape of the stools, the solemnity of the figure of Christ). From Parma, on the other hand, comes a masterpiece like the Healing of the Blind Man, placed next to a Consegna delle chiavi by Giovanni Battista Castello (already attributed to Giulio Clovio), a somewhat forced comparison justified by the common recourse to Michelangelo models: the Healing, moreover, is one of El Greco’s works recorded in the old Farnese inventories (in 1662 the work was given to Tintoretto, showing how closely the Cretan looked to lagoon painting during his Italian years), and in all likelihood was commissioned directly by the Farnese. In the setting, the painting already hints at El Greco’s updating of models from central Italy, as can be seen when looking at the porticoed square, foreshortened in perspective. Dating from the Spanish years is the Agonizing Christ with Toledo in the background, which is located in a somewhat secluded room (be careful not to skip it during the visit): a work that already exhibits all the characteristics of El Greco’s maturity, it does not, however, disregard comparisons with Michelangelo, especially in its setting and pose (it is compared with a Christ Crucified from the area of Marcello Venusti, directly derived from a Michelangelo archetype, and with a Silver Crucifix from the workshop of Guglielmo della Porta). TheOration in the Garden in the parish of Santa María la Mayor in Andújar also belongs to the Spanish period: an alienating painting in which the Gospel episode appears as it might appear in a dream, with the elongated figures typical of El Greco’s mature production, the glimmers like blades of light cutting through the clouds, the deformed landscape almost entirely devoid of references, and the draperies of the apostles that seem almost to live a life of their own. For some reason the work is juxtaposed with a Deposition by Jacopo Bassano (an unspecified reference is identified, but one finds it hard to discern), and the dialogue between the St. Martin and the Beggar of the National Gallery in Washington, one of the best-known works known works by El Greco and one of the exhibition’s highlights, and the counterpart work by Jacopo Bassano, while the comparison between Theotokópoulos’s wispy St. John the Baptist and Titian’s from the Gallerie dell’Accademia seems more pointed: the Greek’s saint is no longer the imperious Titianesque athlete, who does not seem in the slightest to have been shaken by the wanderings of the desert, and whom El Greco may have had in mind when he painted his John the Baptist, but he is a visibly suffering man, emaciated, ravaged by deprivation, depleted of strength, despite the solemnity of his figure silhouetted against a landscape in which the outline of the Escorial can be seen in the distance (it was typical of El Greco to paint real views in his works).

The seemingly less logical comparison between El Greco’s Holy Family with Saint Anne and Correggio’s Madonna Bolognini, on loan from the Castello Sforzesco, deserves a separate discussion. Zavatta and Bigi Iotti’s essay in the catalog attributes to Doménikos Theotokópoulos a particular interest in Correggio’s art, evidenced by a copy, currently missing, of Antonio Allegri’s Night kept at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden. This copy, which presupposes a direct view of Correggio’s original, would also be useful in convincingly fixing an Emilian sojourn of the Cretan painter, hitherto hypothesized by much of the criticism but not documented. The copy of a work by Correggio reinforces the idea that El Greco sojourned between Parma and Reggio Emilia, and we could also say that it corroborates to some extent the idea that the Hellenic painter was somehow fascinated by Correggio’s art: however, it is difficult to go further, difficult to find Correggioesque elements in his paintings, and the comparison between the two works does not help, unless we want to remain on a generic level. The caption in the exhibition speaks of a work in which “El Greco deploys a language of profound delicacy, intimacy and tenderness.” beyond the fact that this scene, so intimate and so loving in its treatment of the theme of motherhood, represents a hapax in El Greco’s production (it was a genre that did not suit him, evidently), it is also worth considering that, if we want to take the most early, it follows his departure from Italy by about fifteen years, and one struggles to think that so long afterwards the memory of his stay in Parma could have flashed through his mind, all the more so since Correggio was not a constant reference for his production as were a Tintoretto, a Titian, but also a Bassano or a Veronese.

El Greco,

El Greco,

After a passage that deals rather hastily with the subject of Grecian portraiture (it is instead developed in decidedly greater depth in the catalog, with an essay by José Redondo Cuesta), we move on to the two most spectacular rooms of the Milan exhibition, devoted to El Greco’s religious production, read in the light of its historical context. Toledo, the panels in the exhibition remind us, was the first city to implement the decrees of the Council of Trent: the Counter-Reformation, in Spain, thus arrived in this city earlier than elsewhere. There goes El Greco’s visionary, crazy sacred theater, made up of dramatic, intense performances, aimed at seeking the maximum involvement of the faithful, who were to feel part of the scene itself: this is what one feels when observing, for example, the Spoliation of Christ, which projects the viewer into the scene by throwing him or her into the crowd surrounding Christ, seraphic and dignified, totally heedless of what is happening around him, despite the oppressive crush that occupies every space making it impossible to glimpse the slightest piece of landscape, and allowing just the sight of a few flashes of sky in the distance. One almost has the feeling of being there, of being present, of having been put in front of Christ who advances bound and dragged by his tormentors, but without breaking down: it is a work that still retains a certain degree of naturalism, despite the elongation of the figures, despite the waxy coloring of the faces, despite the metallic folds of the robes. The same cannot be said of the works that surround it, starting with the great Baptism of Christ, begun around 1608, left unfinished by El Greco and then completed in 1621 by his workshop assistants. El Greco creates here an entirely artificial world, the figures are now intangible presences, heaven and earth merge, no law of physics is respected anymore: what we see on the canvas is pure artifice, pure mental vision, pure ecstasy. The solemnity, the sidereal distance of Byzantine icons lives on in the sacred theater of the Catholic Counter-Reformation: therein lies, perhaps, the pinnacle of the originality of El Greco’s art. Also taking on the tones of mystical epiphany is theIncarnation on loan from the Thyssen-Bornemisza, which follows the stay in Italy by some 20 years (it is work of 1596-1600), and which tackles the sacred theme by restoring it in the form of an overwhelming mystical fantasy in which we seem to be sucked in, swallowed up by the vortex of clouds and cherubim, with the dove of the Holy Spirit swooping down, the angels playing haphazardly, the air and sky invading space. Where did such visual overbearingness come from? What Palma Martínez-Burgos García writes in her essay is interesting, placing El Greco’s art within two poles, that of eloquence and devotion, cast in the context of the Counter-Reformation and the renewed ideological demands following the Council of Trent. “El Greco,” writes Martínez-Burgos García, “was the first master in the Hispanic sphere to masterfully combine emotional formulas to put them at the service of faith,” devising a singular language in which the gestures, mimicry and poses of the characters assume central importance as they are functional in making Greco’s rhetoric effective. To this it should be added that, reworking what he learned in Venice, “El Greco astounds in the management of light and shadow marked by the most rigorous Venetian and antivasarian tradition,” applying color with disunited brushstrokes that amplify “the psychological sense of the unfinished,” creating powerful lighting effects that emphasize and reinforce the religious significance of his complex figurations.

The exhibition continues with a small section devoted to the face of the Madonna, resolved with some, intense paintings with a Marian theme: we admire, on the same wall, a masterpiece such as the Madonna and Child with Saints Martina and Agnes from the National Gallery in Washington (curious detail of the initials of Doménikos Theotokópoulos on the head of the lion below), and the delicate Holy Family with St. Elizabeth and St. John arriving from Toledo, a work in which, writes Juan Antonio García Castro, “El Greco’s painting technique is manifested in all its fullness : from the clouds in the background that hint at the preparation of the canvas to the final glazes, passing through the modifications of the original idea-revealed by radiological images-and the use of aesthetic artifices such as dense pasty brushstrokes or contours executed with organic black to give volume or create a feeling of separation [....], a sought-after effect by which the infant seems to levitate above its mother’s lap.” Next door, the impressive oval with theCoronation of the Virgin introduces the last rooms, where the saints of El Greco’s pantheon parade, from the monumental St. Sebastian of Palencia Cathedral, painted shortly after the painter’s arrival in Spain, and thus when he still had in mind the ancient statues seen in Rome, to the fascinating Magdalene of Sitges via the St. John the Evangelist and St. Francis of the Uffizi. In the penultimate room, on the other hand, are gathered the saints of El Greco’s late maturity, a period in which the painter recovers the hieraticity of the Greek icons on which he was trained, proposing images of saints in frontal pose, solemn, without additional elements to disturb the dialogue with the relative. One admires works such as the paintings of the Apostolate series, or the Christ Carrying the Cross of Olot, and is measured by a painter who dilutes his visionary flair in favor of more intimate, more psychologically meditated, perhaps even more suffered images, which aim to touch the feelings of the faithful in unprecedented ways. The surprising finale is reserved for the Laocoon: the only canvas of mythological subject painted by El Greco, it is a work executed by the painter at the end of his career, placed just before the end credits to bring the audience back to the painter’s ties with Italy, to what El Greco may have seen in Rome. The reference is to the Laocoon group, found in 1506, from which El Greco’s image is evidently inspired, ambiguous and able to digress from the myth, with the introduction of some figures that are difficult to interpret, and all set, as always, in the landscape of Toledo, which we see represented in the background, an image of his adopted city that returns repeatedly in Doménikos’ visions.

The Laocoon is a sort of concluding twist in an itinerary that succeeds in dazing the visitor with the sheer power of El Greco’s imagery, to the point that the smearing of the tour itinerary, which first follows a strictly chronological criterion, then from mid forward it suddenly changes register by reversing the itinerary into a succession of thematic rooms, with the result that one struggles to understand who the painter is who leaves Italy and, once he arrives in Spain, takes little time to completely change his way of painting. He is, essentially, an artist who learns to paint between Venice and Rome, but he probably feels that working in Italy is too difficult for a Greek who paints in the vein of the Venetians and has been deeply marked by the art of Michelangelo. His art is perhaps best spent in Spain, but not in the Madrid of Philip II, but in the cultured but more peripheral Toledo, where he is alone, where he feels no pressure, where he does not feel the weight of comparison with those he perhaps feels are unattainable, where he has no constraints, where he is freer to experiment. Only in such a context could such a revolutionary artist have sprouted, an artist who, as the 2015 Treviso exhibition recalled, found his genius in blending Orthodox and Roman Catholic culture while managing not to deny either language. Hence his nonconformity that does not, however, deny classicism: he absorbs it, rereads it, even upsets it, but it is never denied. One admires here that artist so modern that he seduced so many of the greats of the twentieth century.

It is difficult, for example, to look at a work by El Greco and not think of Cézanne. Or Picasso. Or the Expressionists: in 1911 an exhibition of the collection of Hungarian collector Marczell Nemes was organized in Munich, which included a dozen paintings by El Greco. And one hundred years later, an exhibition was mounted in Düsseldorf that, building on that exhibition, probed the ways in which early 20th-century artists came into relationship with El Greco. Kandinsky, Macke, Kokoschka, later also Max Ernst. In the early twentieth century people admired El Greco for his ability to construct forms sustained by a powerful emotional force, for his anti-naturalism, because he was an artist who set his compositions on rhythms and structures that were first and foremost interior. El Greco, in essence, had opened a path, which would be traveled three hundred years later.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.