To identify the exhibitions curated by Marco Goldin, the art historian-entrepreneur who for years has been grinding out thousands of visitors with his Linea d’Ombra exhibitions, a few years ago a very effective term was coined, “panettone exhibitions,” which well sums up the characteristics of the products signed by the Venetian curator: exhibitions of poor quality, built around a few good paintings and a lot of fillers, calibrated on the ineffable “emotions” they promise to make the paying public feel, exhibitions that leave visitors exactly as they found them, and exhibitions that, in their condition of pure entertainment products, do not advance studies and knowledge one iota. They are, in practice, the artistic counterparts of the movie-panettoni that rage under the holiday season.

It was hoped, admittedly very naively, that two years of forced pandemic stop had led Shadowline and Goldin to revise the established pattern: the first post-pandemic appointment, From the Romantics to Segantini. Stories of moons and then of gazes and mountains, an exhibition set up at the excellent Centro San Gaetano in Padua and open until June 5, confirms, on the contrary, that the approach is still the same that had characterized the previous sorties. Above all, it will be remembered, Van Gogh between the Grain and the Sky, which does not exactly rank among the most exciting events of its exhibition season. It was necessary to understand it right from the title: not so much the by now invasive “from this to that” that has assailed even the most serious occasions (in the end, at best it is a matter of offering the chronological extremes of the exhibition, at worst of attracting the public with some high-sounding name), as the subtitle with that pleonastic “then” that would like to cloak the triad of themes that should constitute the backbone of the exhibition with a further poetic vein. It is a kind of manifesto, in short. And a declaration of hostility toward those who, reading the second subtitle (“Masterpieces of the Oskar Reinhart Foundation”), would perhaps expect an exhibition to be about collecting.

The assumptions, indeed, would have been there. Even if the modus operandi is always the same: Goldin borrows en bloc a large part of a single collection, and he glamorizes an exhibition around it. And when pieces of collections from other parts of the world arrive en bloc, the premises are never the best. This time, however, an eventual scientifically impeccable exhibition could have its justification in the presentation of the choices of Oskar Reinhart, the son of a prominent businessman from Winterthur, Switzerland, who cultivated a strong interest in art from a young age and as early as the 1920s, in his early thirties, started his own collection to devote himself to it full-time starting in 1924, when he left the family business, bought the villa “Am Römerholz,” and made it the home of his collection and then opened it to the public in 1940. The nucleus that arrives in Padua, admittedly, is minimally representative: Reinhart’s collection includes hundreds of works, now divided between the Kunstmuseum in Winterthur (in 1951 the collector left part of his works to his city) and the Am Römerholz villa, where the bulk of the collection is located. A group of works from the Kunstmuseum arrived in Veneto. In any case, even with a nucleus that focuses on only one of Reinhart’s many interests, and moreover not even the one he was most passionate about (his preferences leaned mainly toward French painting), it would have been a more than valid and more than interesting story to tell in an Italian exhibition: all the more so since this is the first time that such a relevant nucleus of Reinhart’s collection has come to Italy.

But no: the curator preferred to daze the public with a rant about moons, gazes and assorted ammenities with the idea of allowing the visitor, reads the introduction penned by Goldin himself, “to orient himself perfectly within Swiss and German art of the 19th century.” There would be much to discuss about Goldin’s consideration of his visitor: to take one example, a complete overview of sixteenth-century Florentine art cannot be obtained by visiting the Uffizi. Can anyone really think that the public here is so clueless as to be able to buy into the fola of perfect orientation in Swiss and German painting of the nineteenth century? We are talking about a selection of about seventy works spanning nearly one hundred and fifty years of German art history, from Romanticism to Divisionism, and all coming from one collection. One can expect to derive a good map to begin moving through a decidedly varied and articulate landscape, but nothing that will guarantee perfect knowledge. And in fact if this is the goal, the exhibition fails miserably, as there are so many and too many gaps: the Nazarenes, who are one of the most original expressions of German art of the first half of the 19th century, just to advance an example are not even mentioned (which is completely obvious: they are not in the collection).

The first two rooms of the exhibition are the best thought out, although with a dozen or so works they claim to cover all landscape painting in Switzerland from the late 18th century until the 1860s. In any case, by and large, the first section holds: on the one hand, the works of Caspar Wolf, which welcome the visitor, and on the other those of Alexandre Calame and Barthélemy Menn, show a development from the idea of the sublime, through the French painting of Corot to more advanced experiences such as those of Robert Zünd, Rudolf Koller, and Frank Buchser, with works arranged in a small room that introduces the second section.

It goes back to the early nineteenth century, but with a logical transition that can still hold, since the theme of the Sublime encountered in the first section can only lead to a brief lunge into Romantic painting, where the best of the exhibition is concentrated, namely the five paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, above all the White Cliffs of Rügen that are among the most interesting pieces in the exhibition. It is not clear by what criterion, right in the middle of the string of Friedrich works, a small canvas by Johan Christian Dahl was also placed, which confuses the audience (probably because of relevancy of themes and format), but it is not the first jarring in a set-up that, as will be seen, forces visitors into tortuous and unnatural turns and prills. Note how all the exhibition’s communication never scratches the surface: we know, therefore, that Friedrich, “in a poetic and touching way” (so the room panel), “combines the sometimes microscopic loss of observation with vast contemplation, thus transcending from the element merely related to physical seeing to the psychological one,” but we are not told why he does so. We know that “the figures who turn their backs to us and look at the landscape make space acquire a sacred identity” and that “in this sense, Friedrich painted pictures in which a full fusion between figures takes place, on a limit that soon becomes limitless,” but the painter’s presence arrives as an epiphany after landscape painting and not as the continuation of a historical path: lacking, in this exhibition, any attempt at even minimal contextualization. This is understandable, since with the selection proposed by Goldin it is an almost impossible feat to reconstruct a century of German painting in a precise and accomplished manner, but it is not justifiable if the purpose of the exhibition is to provide a compass for the public. Let us be content to see Friedrich as the deity of the exhibition, a role implicitly declared right from the entrance, where an excerpt, devoted to the German painter’s skies, from Goldin’s latest book is reproduced. It is worth quoting a passage from it to give an idea: “Skies that are apparition and enchantment, are a flight of crows as they will be for Van Gogh at the end of his days. Skies that are a journey without end and without possibility of solution. Skies.”

All connections jump starting with the third section: beginning with the room devoted to Arnold Böcklin, all logical sense is lost. Thus, one jumps flatly from Romanticism to Symbolism, where Böcklin is presented as a painter “very particular on the European scene of the second half of the 19th century” and as a “champion of a rather eccentric Symbolism” (talk about perfect orientation), which “had in the ideals and depictions of the classical world its point of supreme interest.” The works of Anselm Feuerbach and Hans von Marées are lined up here just because the two were friends of Böcklin, but there is no way to get a clearer profiling of their contribution to 19th-century German painting. Instead, on the adjoining wall of the room, paintings by Carl Blechen and Christian Morgenstern, landscape painters of the previous generation who obviously had nothing to do with Böcklin and colleagues, appear so suddenly, meaninglessly and without anyone ever calling them out or mentioning them. On the other side of the room Goldin composes a further section, with the slyly titled The Gaze and the Mystery of Silence: a series of portraits by Ferdinand Hodler and Albert Anker that would like to offer an overview of portraiture in Switzerland. So in one and the same room you have on one side themes of myth reworked by the German Symbolists, on the opposite wall portraits of two Swiss painters, and on the one next to it views of the pioneers of realist landscape in Germany, never mentioned in any panel.

If the exhibition reaches the height of confusion here, in the next room, The Tale of Life, the visitor is called upon to disentangle a congeries of paintings that are equally heterogeneous but which the curator attempts to hold together due to the fact that all the painters (ten, for twenty works), covering a span of time beyond any manageable length for a single room from which a linear discourse is to be derived (they range from Carl Spitzweg to Max Slevogt: the latter born sixty years after the former), deal with situations that have to do with “life,” as per the title of the section. And in fact there is everything in the room: we start with Waldmüller’s landscapes juxtaposed with Menzel’s, after which, if one wants to try to follow a thread, one has to turn a hundred and eighty degrees and find oneself in front of Spitzweg’s Painter in the Garden juxtaposed with Liebermann’s Playground (the reason for the comparison escapes us: perhaps because of the similar setting). Next come landscapes by Hans Thoma and Wilhelm Trübner, which together return an appealing color juxtaposition. We then enter the room diagonally and look at the works of Franz von Uhde. Figures, in this case: the Elder Sister and the Girl Reading until you reach Lovis Corinth’sSelf-Portrait. One leaves by letting Max Liebermann’s Street at the School in Edam and Max Slevogt’s Bathing Establishment on the Havel pass by. The last part of the exhibition is dedicated to the mountains: it opens with the best piece in the show, Segantini’s Alpine Landscape with Woman at the Fountain, and continues with works by Giovanni Giacometti, Cuno Amiet and Ferdinand Hodler (a small room is all about his Alpine landscapes) to reach the finale with Hodler’s Looking into Infinity by Hodler himself. Which with snow and mountains has absolutely nothing to do with it, but allows for the striking closure typical of Goldin’s exhibitions.

It should be noted that From the Romantics to Segantini is the first in a series that aims to restore to the public a fresco of the situation of painting in Europe throughout the 19th and part of the 20th century. There is also the title of this multi-stage mega-project: Geographies of Europe. The Plot of Painting between the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. If it was intended to begin with a similar disaster on Swiss and German painting, Goldin’s intention sounds more like a threat: it is therefore to be hoped that the score will change with the upcoming dates. Wanting to mitigate the judgment on an exhibition that lacks a credible structure and a logical path, one could at best say that From the Romantics to Segantini is, at best, a missed opportunity to talk about a collection: throughout the entire itinerary there is not a line that speaks of Reinhart and the vicissitudes of his collection. One gives the benefit of the doubt to the audioguide, which the writer did not use: in any case, the audioguide should not be a substitute for the panels in the room (and in fact the tool contains an account of Goldin’s exhibition and therefore, at least in theory, should not take anything away from those who do not use it, also because the outlay for renting the device is considerable: 6 euros and 50, to be added to a whopping 15 euros for the exhibition, very high figures for the product being offered, and what’s more with an absolute ban on taking photos, even of the panels).

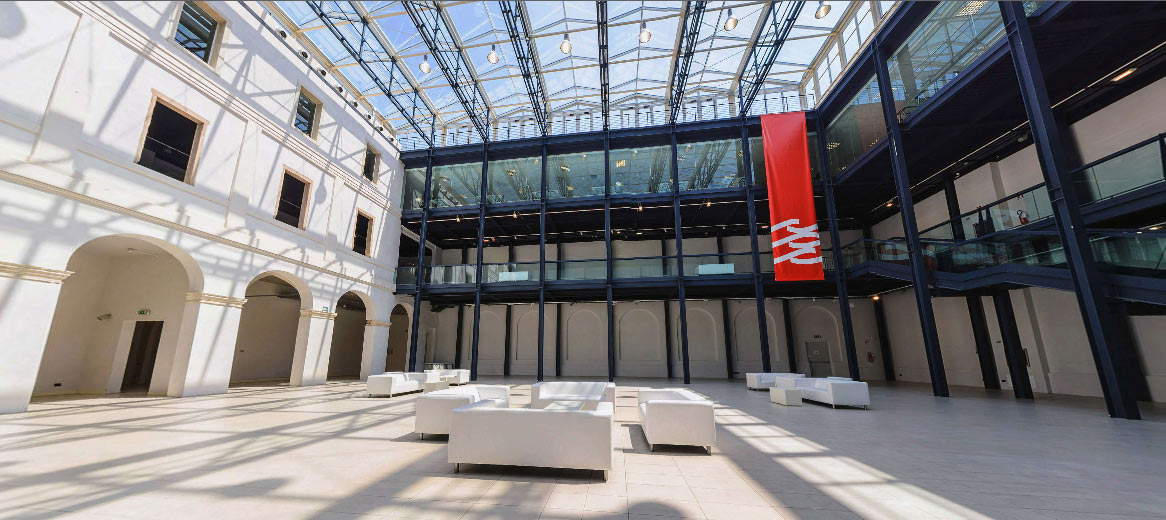

It is a pity that it touches to speak of a missed opportunity because, moreover, from this point of view the catalog turns out to be an interesting tool, with a long essay by Goldin devoted precisely to the formation of Reinhart’s collection. It is the first publication in Italian on the Reinhart collection: this should be acknowledged, also because it opens a glimmer of novelty on the cliché of the exhibition-banettone. Lastly, the restful, near-perfectly lit set-up deserves a special note: for those who want to see a selection of Swiss and German painting in excellent lighting conditions, the rooms are ideal. Catalog and set-up alone, however, do not make the exhibition sufficient. And if the only valid reason to go in person to see the exhibition is because Padua is more easily accessible than Winterthur, something is certainly wrong.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.