Like the metatheater that places the theater itself, Castrum Superius, as the object of the play. The Palace of the Norman Kings is a meta-exhibition, in which the most daring project of the entire Middle Ages in the Mediterranean, the palace-fortress built by Roger II, the “Castrum Superius” precisely, once contrasted with the “Castrum Inferius” (Castellammare), is itself the subject of the exhibition. The exhibition, in fact, tells of the medieval physiognomy of the building, from the earliest stages of construction until the sunset of the Norman reign. Hosted, from May 15, 2019 to January 10, 2020, at the Duca di Montalto Rooms of the Royal Palace of Palermo, it is the result of an inter-institutional project of the Frederick II Foundation, in close collaboration with the Sicilian Regional Assembly, the Department of Cultural Heritage and Sicilian Identity, the Regional Department of Cultural Heritage, the Superintendence for Cultural Heritage and the Regional Center for Design and Restoration.

The palace “is of the city and the world,” reads the preface to the catalog. The entire exhibition is set up to make visible this concept, with which the Frederick II Foundation, for the past year and a half, has been embarking on a new course of “extroversion,” of thoughtful consideration of visitors. After centuries, the monumental door to Parliament Square has been reopened and the “medieval tunnel,” the corridor that gives access to the exhibition rooms, has been given new light; the so-called “rimessone,” the large room of the palace accessed from the same square, has been arranged; the Royal Gardens have been reopened “to the city,” which can be enjoyed independently of the visit to the palace (at a cost of 2 euros). And, then, beyond the portal, the restored entrance hall houses, since last September, an elegant store with creations specially made by Sicilian artisans inspired by the iconographic motifs of the Hall of King Roger and a selection of art books.

|

| Castrum Superius Exhibition Hall. The Palace of the Norman Kings |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Castrum superius. The Palace of the Norman Kings |

The exhibition

As the monument’s multi-millennial history tells of the meeting of different civilizations and cultures, unsurpassed in the Palatine Chapel, “the most beautiful thing that exists in the world” (Guy de Maupassant), “the wonder of wonders” (Oscar Wilde), where Romanesque architecture, Byzantine mosaics and Islamic painting coexist, and where, immersed in a profusion of ornamental and calligraphic motifs, parades the extraordinary variety of subjects that make up the court of Roger II with its heterogeneous cultural coexistence, so the Palace recounted in the exhibition once again becomes a symbol, as it was in ancient times, of coexistence among peoples.

Consistent with this cultural message, there is not, according to custom, one or more curators, but a collegial curatorship that coincides with a scientific committee whose members include Vladimir Žorić, Henri Bresc, Maria Concetta Di Natale, Giuseppe Barbera, Stefano Biondo, Maria Giulia Aurigemma, Maria Maddalena De Luca, Antonino Giuffrida and Stefano Vassallo, who, along with others, signed the essays in the catalog. Published by the Fondazione Federico II itself, the volume comes to constitute an indispensable point of reference for future studies, in which new working hypotheses are advanced (Vassallo, for example, hopes for the continuation of the archaeological excavations that “are revealing an extraordinary potential for writing the history of the site”) and open interpretative problems (such as on the ceiling of the Palatine Chapel, the focus of the essays by Žorić and Aurigemma). Almost like a Greek chorus, the “voices” of scholars comment on what is happening on the scene. And on the scene is him, the Palace, its stones, its furnishings, its art masterpieces, the construction events, the archaeological excavations, the military features, the residential and religious aspect. It is a history that begins to be written in ancient, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine times, which is profoundly rewritten in the Norman era during the “building of the Kingdom” (Bresc), only to be resumed in the era of the viceroys; it is, therefore, “a myth that continues” (Giuffrida) under the Bourbons. A history that continues to be written even today: the palace of the Norman kings is a living seat, where political power continues to be exercised, although this, having ceased those of kings and viceroys, has since 1947 assumed the democratic guise of the Sicilian Regional Assembly.

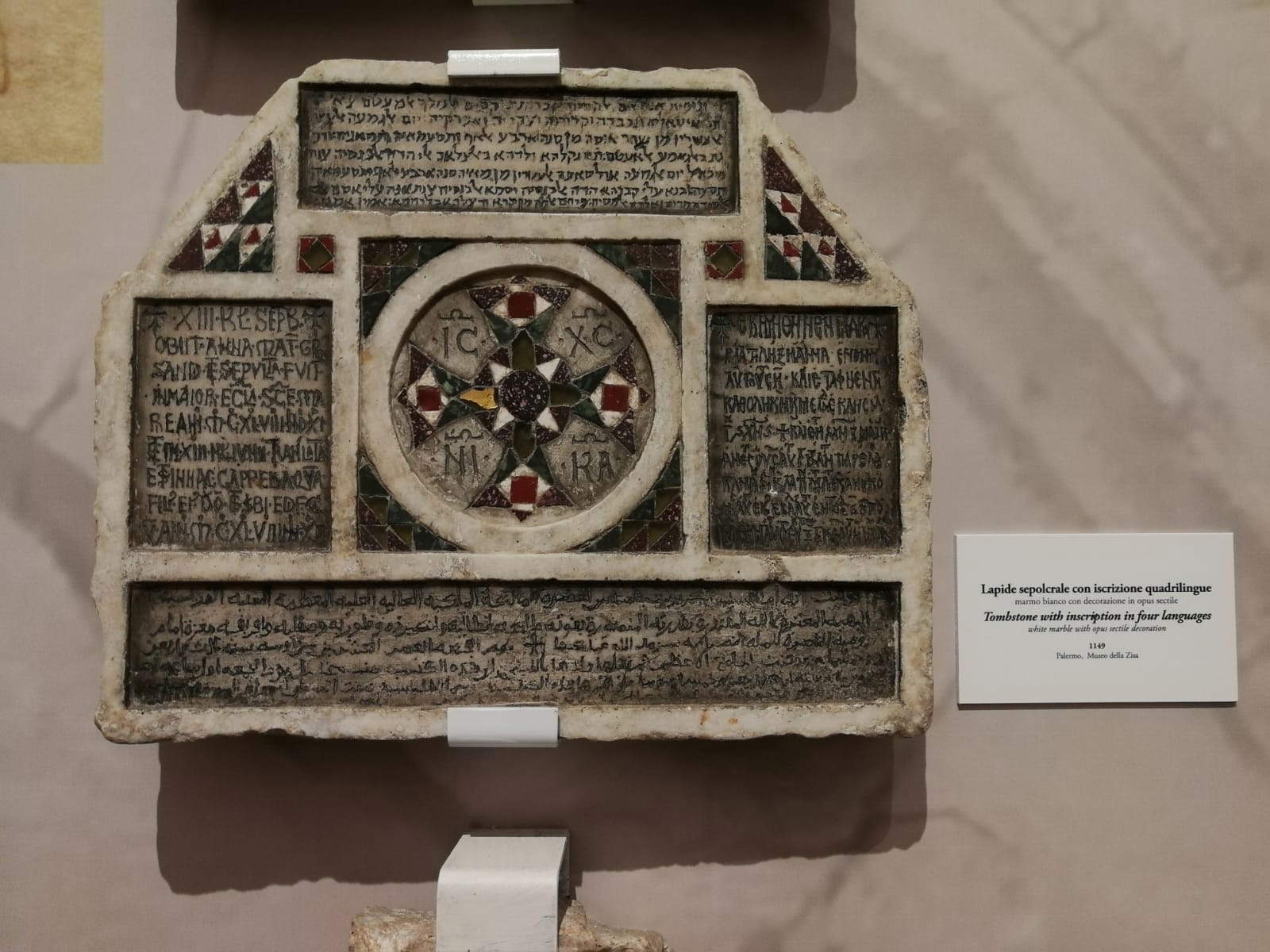

In contrast to an imported “monstrosity” (think of the recent Antonello monograph at the Abatellis or the Caravaggio from the Spier collection at the Syracuse Superintendency), this is an all-Sicilian exhibition, with loans (paintings, sculptures, drawings, coins, ceramics, etc.) from major regional museums and institutions (Abatellis, Bellomo, Regional Museum of Messina, Salinas, Pepoli, civic and diocesan museums, regional libraries, etc.) along with those from the Palatine Chapel, from which the detached fresco of the Madonna Odigitria also comes. To mention only a few, in addition to those that will be mentioned later: from the Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis come theSlabs with Arabic inscription in praise of Roger II from the Palace of Palermo (1130-1154) and the Ceiling Panel from the Royal Palace of Palermo (late 12th century); from the Superintendence of Palermo the tombstone with a quadrilingual inscription (1149) and that with a trilingual inscription (1153); from the Regional Museum of Messina the head of an apostle (12th-13th century), the crutch capital (12th century) and the capital and architrave with combat scenes (12th-13th century); from the Salinas Archaeological Museum coins of Norman coinage; from the Municipality of Mazara del Vallo the Pair of elephants in white marble (first half 12th century) and the pair of lions also in marble (12th century, first half), as well as a Pluteus (first half 12th century); from the Bellomo Gallery in Syracuse a marble basin , with animalistic decoration (12th century) and a small shelf (human protome), in carved marble (12th century); from the Curia of Monreale the two capitals of the canopy of the tomb of William I (second half 12th century); from the Griffo Museum in Agrigento a Pluteus, in marble with faced deer (early 12th century).

|

| The ceiling of the Palatine Chapel |

|

| Ceiling of the Palatine Chapel from the scaffold during the 2005-2009 restoration. Ph. Credit Silvia Mazza |

|

| Odigitria da Calamauro (late 12th century; mosaic; Palermo, Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis) |

|

| Odigitria, detail (12th century; detached fresco; Palermo, Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie) |

|

| Tombstone with quadrilingual inscription (1149; Palermo, Museo della Zisa) |

|

| Section of the exhibition with the two pairs of marble lions in the center |

The Exhibition Sections

The large room that houses the exhibition is approached through a real “liminal” rite of passage from the outside, after passing through the monumental gate and through the “medieval tunnel,” an anti-urban structure, a decompression chamber from the space of everyday life and, at the same time, a homogeneous structure instead to the “other” space in which objects and works of art are subtracted from time. And here the catabasis ad inferos of the tunnel is converted into a cathartic ascent that transcends the physical limits set by the ephemeral setting: above, beyond the temporary walls and movable panels, surviving excerpts of the important cycles of wall paintings commissioned by Luigi Moncada in the 17th century from the most talented painters of the time re-emerge into view. Among these excerpts, the visitor’s attention is caught by the detailed scene of the Hall of the Sicilian Parliament (17th century), by Gerardo Astotino, with the throne reserved for the President and the benches for the three branches of Parliament. This is a refined staging direction that symbolically connects vertically the focus of the exhibition, the section devoted precisely to the “Castrum superius,” to the function of Europe’s oldest parliament.

To emphasize the centrality of this section in the visitor’s itinerary, dividing walls enucleate it from the rest of the exhibition area, conceived as an open space. It is accessed symbolically through the reproduction of the bronze doors of the Palatine Chapel framed by the Slabs with Arabic inscription in praise of Roger II (12th century), which in the same palace must have stood at the crowning of a door. They evoke the Arabic inscriptions in the Palatine Chapel, which exhibit a large repertoire of ad’iya (qualities or virtues required of God for the ruler). In the center of this space almost an invitation to a circumambulatio, that is, to turn in an apotropaic rite around the octagonal-plan support, like the “stars” of the ceiling of the Palatine Chapel, around the two pairs of lions from Mazara del Vallo and the Sala Ruggero of the same Palace. Never as on this occasion has the integrated ticket, exhibition and Chapel (full 10.00 euros, reduced 8.00), its own raison d’être.

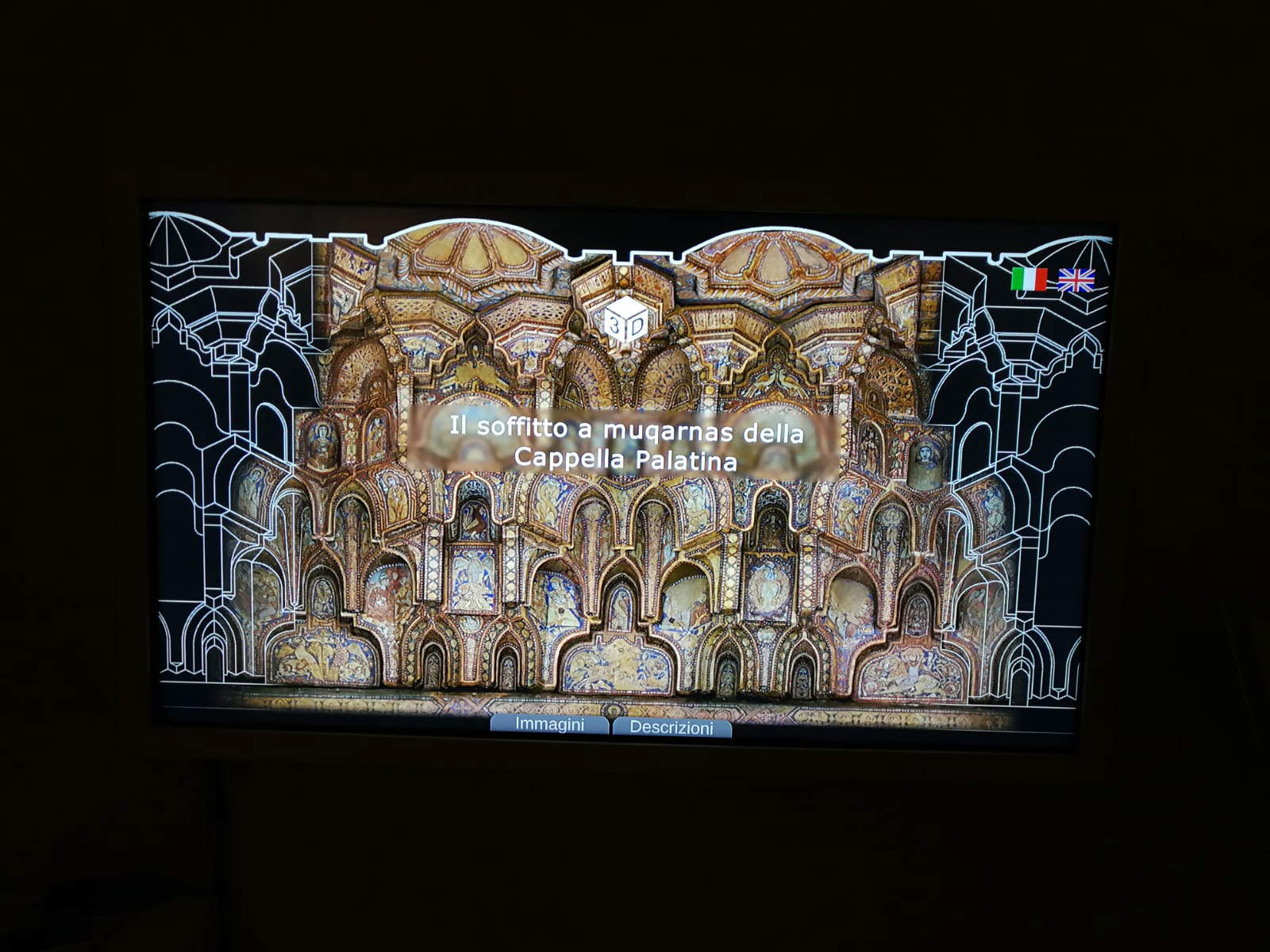

The visitor is left free to move among the thematic sections or to follow the diachronic narrative, which opens with the “Arab Sicily” section, where the center of gravity of theexhibition a rare bronze Candelabrum with openwork decoration, of Iberian scope (10th century), from the Mother Church of Petralia Sottana; to continue with “The County,” itself divided into sub-sections, of which just the most significant pieces are mentioned: “Roger I” section with the Diploma of Duke Roger (1086), from the Diocesan Historical Archive of Palermo; “Constance” with the Codex of Queen Constance (12th-12th century), from the Regional Library A. Bombace of Palermo; “Roger II,” with the Sepulchral Tombstone with quadrilingual inscription (1149), from the Zisa Museum in Palermo; and a marble basin, with refined zoomorphic and phytomorphic decoration (12th century), from the Bellomo Gallery in Syracuse; “William I” and “William II,” where an undulating mount values the nearly four-meter-long parchment with William II’s Platea (12th century) with lead seal, from the Tabulario Santa Maria Nuova in Monreale. Together with the Privilege of Henry VI with gold seal, from the same Tabularium, these are works made known on the occasion of the exhibition. In the Section dedicated to the “Palatine Chapel ”a catalyst element is one of the wooden models of the muqarnas ceiling of the Palatine Chapel (19th century), from the Academy of Fine Arts in Palermo. The catalog reports Žorić’s unpublished study of the construction techniques of its ceiling, which reveals the extraordinary technological invention in the construction of carpentry that allowed for an extreme lightening of the ensemble of muqarnas, small domes and “octagonal stars”: the curved surfaces are formed with juxtaposed laths that do not exceed 5 mm. If they were, instead, made of solid wood, the weight of the ceiling would have been five or six times the actual weight and unable to guarantee structural functioning and its very survival over the centuries. "The oldest ornamental woodwork still in situ in Europe, and also the only one of its kind, " notes Žorić. But in later centuries did this extraordinary invention produce outcomes? I believe that a distant heir of this type of construction can be identified in the extrados warping of light vaults, called “in cannucciato,” made for noble palaces, churches and theaters between 1500 and 1800. Popular because of their inexpensiveness and ease of fabrication, as well as, probably, for the same reason of low weight.

The sections, then, offer a careful selection of works of suntuary art and illuminated codices from the Norman era remaining in Sicily, curated by Maria Concetta Di Natale. One can admire theEpistolarium, from the Painiana Library in Messina, “a very fine manuscript that suffices to testify to the high quality achieved by illuminators in the city of the Straits,” in which the figures of lions recall those in the mosaic lunettes of the Hall of Roger; a significant sampling of precious Ebonnean caskets from the Treasury of the Palatine Chapel; the Arm Reliquary of St. Martian (12th century) from the Treasury of the Cathedral of Messina, “important evidence of surviving Norman sacred silverware in Sicily”; and again the rare (in terms of type, materials and manufacturing techniques) portable Altarolo from the Treasury of the Cathedral of Girgenti, a Byzantine work (13th century).

|

| Showcase with caskets |

|

| Foreground: Plateau of William II (12th century; from the Tabularium Santa Maria Nuova in Monreale) |

|

| Wooden models of the muqarnas ceiling of the Palatine Chapel (19th century; Palermo, Academy of Fine Arts of Palermo) |

|

| Reproduction of the bronze doors of the Palatine Chapel framed by the Slabs with Arabic inscription in praise of Roger II (12th century) |

|

| Rocco Lentini, View with Zisa Castle (1935) and View with Cuba (1922), both oil on canvas |

|

| Copy of Roger’s Mantle (Como; Ratti Foundation) |

|

| Golden Seal of Henry VI |

Surrounding the “center of gravity” of the exhibition, the aforementioned “Castrum superius” section, are the thematic Sections, which illustrate all the functions of the Palace: the Works, the Mint and the Norman Royal Park that extended from the palace across the Oreto Valley. What catches the eye in the "Opifici " section is the copy of Roger’s Mantle from the Ratti Foundation in Como, made for the exhibition on the Normans at Palazzo Venezia in Rome in 1994, to overcome the serious conservation problems of the original kept at the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna. The selection of coins from the Pepoli and Salinas museums documents the importance of the Palermo Mint during the Arab and Norman dominations. While, in fact, “in Europe gold production was suspended following the reforms of Charlemagne,” Lucia Traviani and Giuseppe Sarcinelli explain in the catalog that “the Palermo mint minted gold coinage following an unbroken tradition from the Byzantine and then Islamic worlds.”

Divided, finally, into two thematic nuclei, the “Royal Park” section proposes in the one dedicated to the “Genoard” (from the Arabic Jannat al-ard, earthly paradise) the reconstruction of the images of parks and gardens in Norman Palermo (the catalog essay is signed by Giuseppe Barbera), as seen in the two oils by Rocco Lentini, View with Zisa Castle (1935) and View with Cuba (1922); and the two oils on canvas by an unknown with The Royal Palace of Palermo and The Castellammare of Palermo (18th century).

The exhibition was also an opportunity to experiment with forms of applying the latest developments in digital technology so as to enable the viewer to appreciate details that are difficult to see with the naked eye and to explore the geometric-constructive matrices of the ceiling. The actual exhibition is, therefore, prepared by a video in the corridor leading to the rooms, a touchscreen in the room adjacent to the one hosting the exhibition, and an augmented reality application that, on the threshold of the latter, reproduces a mosaic carpet that comes alive under the visitors’ feet: a dynamic interpretation of the theme of liminality, it prevents the visitor from “pulling straight” and immediately captures his or her attention. Restrained for a few seconds in this “statio” he thus has the opportunity to let his gaze wander freely through the narrative continuum by which the tale of the building’s medieval physiognomy unravels in the large, single room.

|

| The augmented reality application |

|

| Touchscreen with 3D reproduction of the ceiling of the Palatine Chapel |

|

| The Royal Gardens |

|

| Passage to Mediterranean, the installation of a dynamic cultural garden on Parliament Square |

|

| Passage to Mediterranean, the installation of a dynamic cultural garden on Parliament Square seen from above |

In theimpossibility of making it, as it would deserve for the historical-documental importance of the reunion of the loaned works, a permanent exhibition at the Palace, the exceptional nature of the arrangement would suggest that its memory be preserved in a specially dedicated catalogue-appendix.

An exhibition, in conclusion, that represents the highest point of the new course of the Fondazione Federico II under the direction of Patrizia Monterosso, which, having archived the past seasons of pre-packaged and imported exhibitions, is distinguished by the realization of original and “zero kilometer” exhibition events with Sicilian works. These include in 2018 Sicilië, Flemish painting, which presented for the first time to the general public, in the freshly restored Sale Duca di Montalto, a significant collection of Flemish paintings (about sixty) found in private and public collections on the island. Prominent in connoting the latter and all other exhibition events is the absence, already pointed out, of one or more curators, in favor of a collegial curatorship delegated, from time to time, to a scientific committee set up ad hoc. With the recovered Giardini Reali and the installation of a dynamic cultural garden(Passage to Mediterranean) on Parliament Square, which evokes in plan the “octagonal stars” motif of the Palatine Chapel, the unitary framework of an enhancement project is recomposed that appears thoughtful and constructed along a line of coherence that makes it a more than rare case in a Sicily that has recently been distinguished by events at the lowest cultural low.

The author of this article: Silvia Mazza

Storica dell’arte e giornalista, scrive su “Il Giornale dell’Arte”, “Il Giornale dell’Architettura” e “The Art Newspaper”. Le sue inchieste sono state citate dal “Corriere della Sera” e dal compianto Folco Quilici nel suo ultimo libro Tutt'attorno la Sicilia: Un'avventura di mare (Utet, Torino 2017). Come opinionista specializzata interviene spesso sulla stampa siciliana (“Gazzetta del Sud”, “Il Giornale di Sicilia”, “La Sicilia”, etc.). Dal 2006 al 2012 è stata corrispondente per il quotidiano “America Oggi” (New Jersey), titolare della rubrica di “Arte e Cultura” del magazine domenicale “Oggi 7”. Con un diploma di Specializzazione in Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna, ha una formazione specifica nel campo della conservazione del patrimonio culturale (Carta del Rischio).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.