An exhibition that sets out to reknit the threads between Dante Alighieri and Florence, reconstructing the process of reappropriation to which the poet was subjected in the years following his death, and following the dissemination of his writings, can only be an eminently political review: walking through the rooms of the National Museum of the Bargello in Florence where the exhibition Honorable and Ancient Citizen of Florence has been set up. The Bargello for Dante means, therefore, to read the plots of a story that is first and foremost political. It is necessary to refer to political reasons in order to understand why, in the fourth decade of the 14th century, in the Chapel of the Podestà of the Bargello (which is an integral part of the exhibition’s itinerary), it was decided to include the effigy of Dante among the ranks of the blessed of Paradise, just as it is necessary to know the political situation of Florence at the time in order to trace the origins of the success of the Divine Comedy and other texts by Dante that many people in 14th-century Florence already knew and commented on. Politics, then, along with art and literature: holding this installation together is the history of early 14th-century Florence that emerges from the frescoes on the walls of the palace where the sentence that condemned Dante to exile was pronounced, from the gold fonds arranged along the rooms, from the illuminated codices, and from the manuscripts.

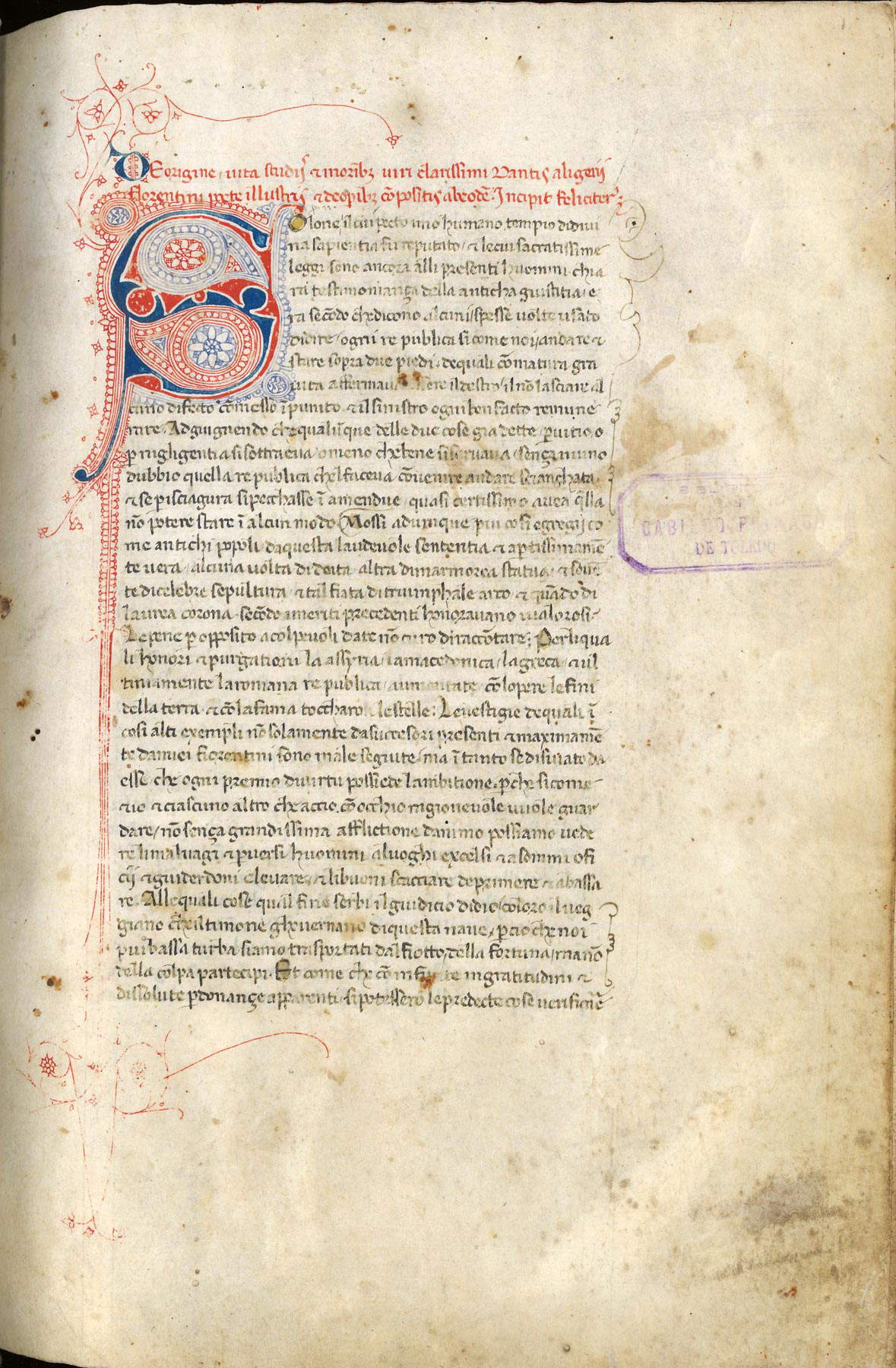

It is a review that covers a very limited time: from Dante’s condemnation to the 1940s and 1950s, a period in which two events occur that constitute the exhibition’s termini ad quem. The first is the publication of Giovanni Villani’s Nuova Cronica, in which Dante is defined, as per the title, as an “honorable and ancient citizen of Florence” (and is thus by now completely rehabilitated): it is interesting to note that in the Cronica the chapter on Dante, in addition to constituting the first biography of the poet that has come down to us, also acts as a caesura in an account of war events, a fact that underscores the importance that Dante’s stature must have assumed in the eyes of Villani and the Florentines of the mid-century. A biography, to be sure, filled with inaccuracies, especially with the events that followed the exile (Villani, not being an eyewitness to what happened to the poet after 1302, had to rely on third-party sources), but one that gives an account of the esteem in which the cultured circles of mid-century Florence now held the poet. The second is Giovanni Boccaccio’s compilation of the Trattatello in laude di Dante, the first draft of which is contained in Toledano codex 104.6 (present in the exhibition), and in which the author of the Decameron did not hesitate to express his displeasure at the treatment Florence had reserved for the Supreme Poet, the “most clear man Dante Alighieri,” who, “an ancient citizen nor of obscure relatives born, how much for virtue and for science and for good operations he deserved, much the things that appear from him show and will show: which, if in a just republic they had been performed, no doubt there is no doubt that they had not set him up for very high merits.” And instead, Florence reserved for Dante “unjust and furious damnation, perpetual disbandment, alienation of paternal goods, and, if it could have been done, maculation of the most glorious fame.”

These are the extremes between which the exhibition itinerary is placed: In between, a series of events, such as the construction of the Podestà chapel and its fresco decoration by Giotto and his workshop, the reception of the Comedy in the 1430s and 1440s, the development of a Dantean imagination that pervades the works of the artists of the time, the circulation of the works of the classics, the evolution of a Florentine vernacular that was not only a literary language but also a practical one used in science, economics, markets, and even in cooking. An exhibition that, inform the three curators(Luca Azzetta, Sonia Chiodo and Teresa De Robertis), is the result of two decades of research that have essentially focused on two aspects: “on the one hand the material tradition of Dante’s works, and on the other the ways in which the Commedia was interpreted and composed by its first readers.” It is worth noting that this exhibition is the result of a collaboration between the Bargello Museums and the University of Florence: the multidisciplinary nature of the exhibition is, moreover, one of its strong points, since to immerse oneself in the narrative of the exhibition is not only to learn about a political history, but also, in some ways, to learn more about 14th-century Florence.

|

| Exhibition Hall |

|

| Hall of the exhibition |

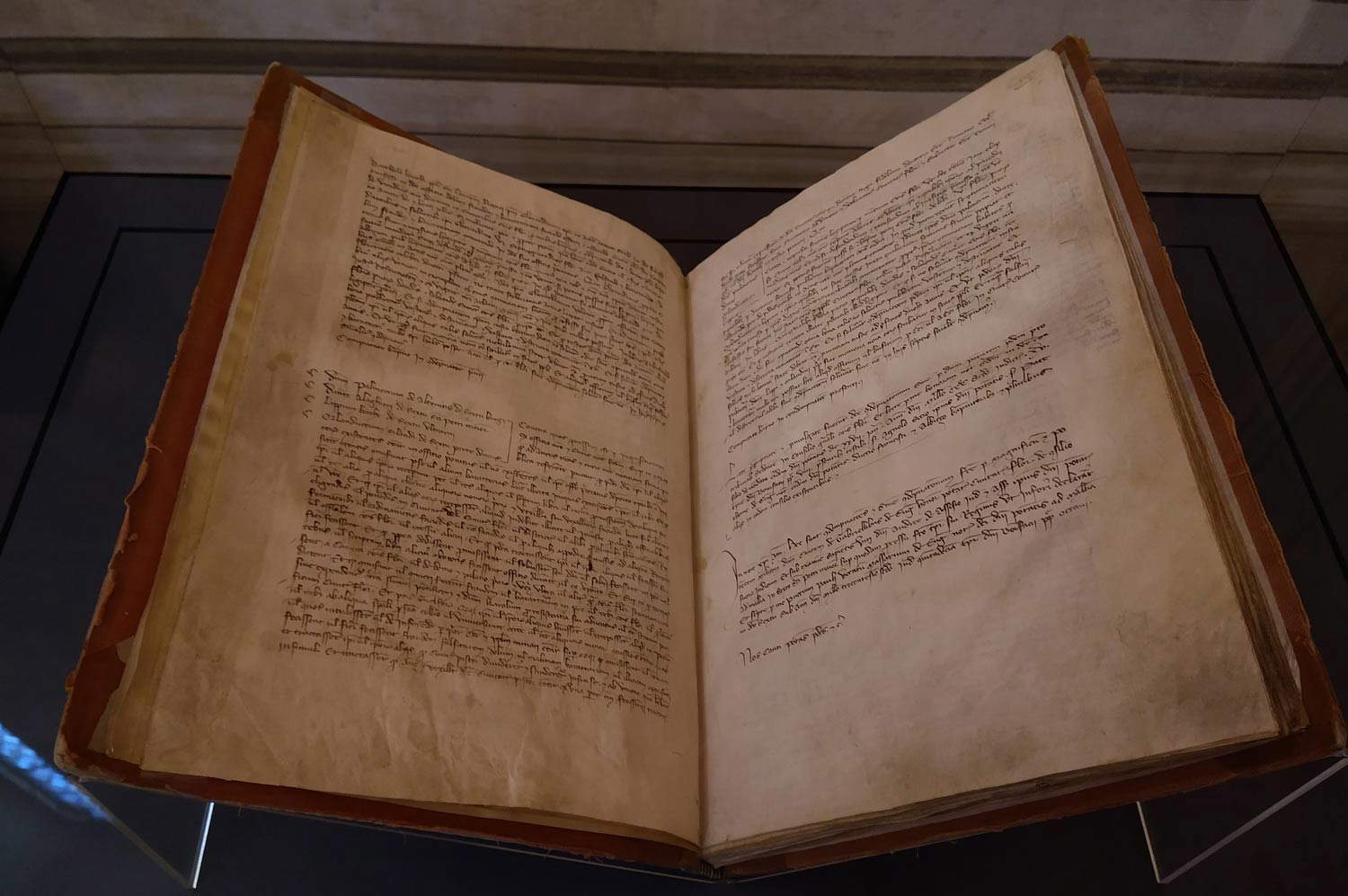

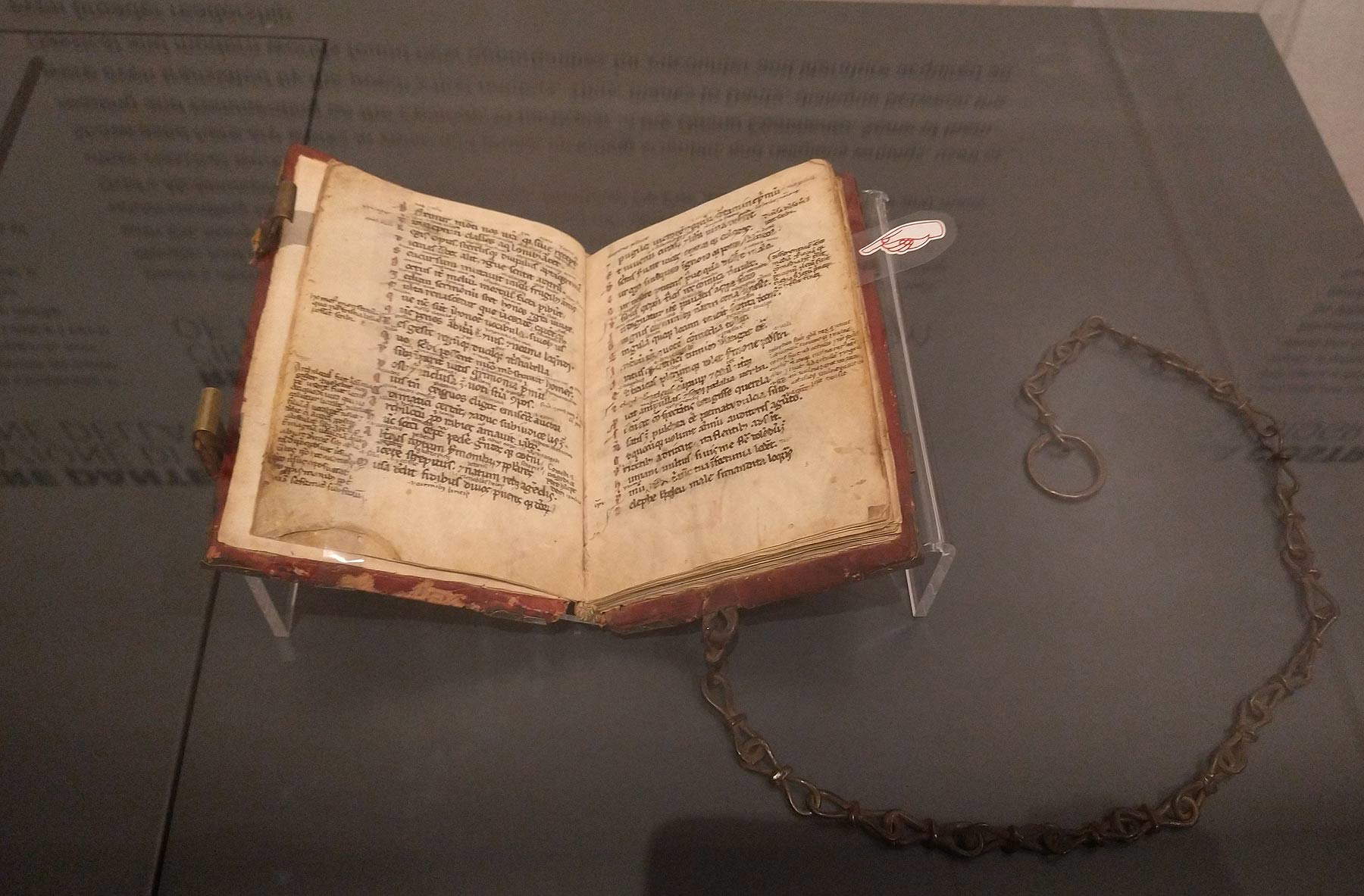

That is, that same Florence that first cast out Dante with ignominy, and then redeemed the poet’s memory. And it is from here that the tour can start: not from the rooms on the ground floor, but directly from the Cappella del Podestà, where the frescoes by Giotto and his collaborators are unveiled to the public for the first time after the conservation work of the last few months, the installation of the new lighting system and the new layout of the chapel itself and the adjoining sacristy. The objects on display in the showcases evoke the events of 1302, but also the symbolic role of what was then the Palazzo del Podestà (i.e., the current site of the exhibition), an “exemplary case study,” writes Sonia Chiodo in the full-bodied and demanding exhibition catalog, “theater and symbol of a power that made use of the communicative capacity of the figurative arts to exhibit the values on which the administration of justice in the city was based, to ’publicize’ exemplary sentences and humiliate the enemy but also to celebrate its own magnanimity.” The first object one encounters, from the State Archives of Florence, is a volume of judicial documents that also includes the sentences of January 27, 1302 against the white side of the Florentine Guelphs (these are the oldest copies that have come down to us: the originals were lost in the fire that was set to the Florentine archives in 1343, in the excited days of the expulsion of the Duke of Athens). Convictions that history has branded as a revenge of the Blacks against the Whites rather than as the result of reasoned judgments: Dante, in particular, was accused of bartering, a crime that included traits of the modern misdemeanors of bribery and embezzlement, and very serious even for the morals of the time.

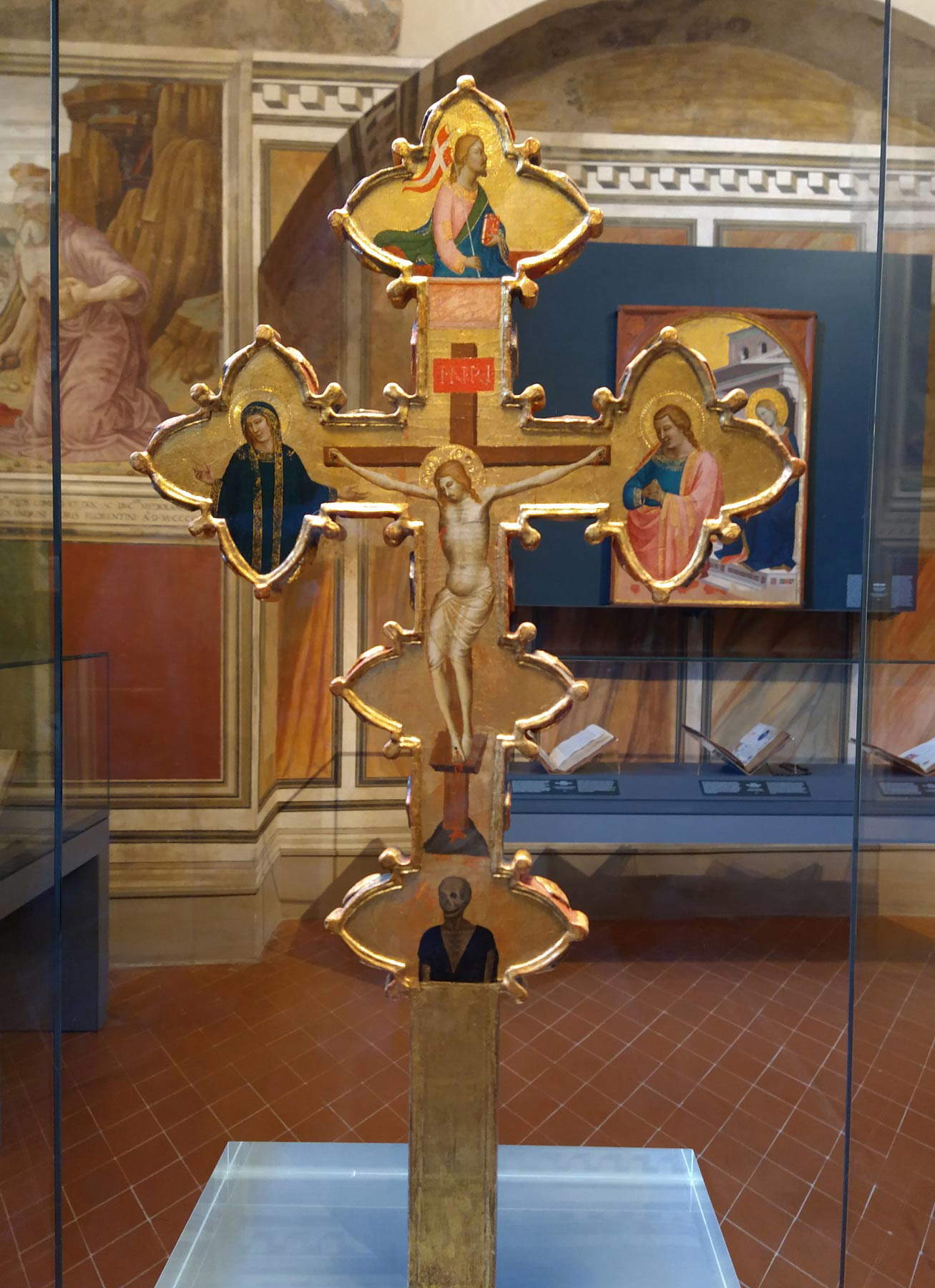

The sentences had found his appointment as prior in 1300 to be irregular, as it had come as a result of bribery, and in turn Dante had allegedly manipulated the election of subsequent priors. Along with Dante, fourteen other members of the white party were condemned, all of whom shared the commonality of having served as prior in previous years. The poet, condemned in absentia, had been ordered to be confined from Tuscany for two years, to be perpetually excluded from public office, to pay a ban of five thousand florins (a considerable sum), and to return the economic fruits of his illicit activities (although the sentences do not specify the amount), on pain of confiscation and destruction of his real estate. None of the fifteen convicts appeared in court for the dation, and the Blacks exacerbated the judicial repression by transforming, for all the convicts, the banishment into a death sentence with a sentence of March 10, 1302: if Dante had returned to Florence, he would have been burned at the stake. This is the end that, on September 16, 1327, came to the poet Cecco d’Ascoli, condemned for heresy by the Franciscan inquisitor Accursio Bonfantini, although we do not know the exact reasons for the sentence: recent studies, recalled in the catalog by Sara Ferrilli, hypothesize that the affair is to be seen in the context of the inquisitorial policies of Pope John XXII, who saw in the elimination of prominent figures the opportunity to get his hands on their wealth. A reminder of this affair is on display in the oldest figured codex of Cecco’sAcerba: a kind of polemical response to Dante’s Commedia, of which Cecco was a rival. The specter of the death sentence is also evoked by two particularly significant works: a Barnacle Cross by Bernardo Daddi, circa 1340, which because of its particular iconography (we also find a clothed corpse, reduced to a skeleton) may have been in the possession of a confraternity that assisted those condemned to capital punishment, and a late fourteenth-century tablet by an unknown author known as the “Master of San Iacopo a Mucciana,” which was probably shown to the condemned before they were executed (it will be worth mentioning, however, that we do not know the ritualities of the execution of death sentences in early fourteenth-century Florence).

Looking up, one will easily notice the portrait of Dante in the ranks of the elect in Paradise conceived by Giotto and finished by assistants following his death in January 1337. Sonia Chiodo again reconstructs the reasons that led to Dante’s inclusion in Giotto’s fresco: a leading role was played by Bishop Francesco Silvestri da Cingoli, in office from 1323 to 1341, whose links with the chapel’s frescoes are highlighted for the first time at the exhibition. Silvestri was assigned to the Florentine bishopric by John XXII with the aim, writes Chiodo, of “curbing the arbitrariness of a small circle of magnate families that traditionally controlled the election of the bishop of Florence.” Silvestri’s political role was, therefore, to strengthen the papal presence in Florence. Silvestri’s economic policies (including obtaining a provision that one-third of legacies left to the poor be donated to the episcopal refectory) provided the bishopric with significant economic resources, which also directed the cultural policy of the curia. According to Chiodo, Silvestri was also the promoter of the decoration of the Podestà chapel: the bishop had shown himself favorable to the figure of Dante thanks to the support he provided to his son Iacopo when the latter returned to Florence in 1325 to recover the property that had been seized from the family, and to promote the dissemination of his father’s work. These are circumstances that, according to Chiodo, clarify some of the ways in which the Commedia began to circulate in Florence and why the frescoes in the chapel reflect to some extent Dante’s visionary afterlife. The Florentine review also provided an opportunity for a lunge at Giotto’s conception of the frescoes: Andrea De Marchi ’s authoritative essay intervenes on the subject with precise and timely comparisons with other peaks of Giotto’s production, affirming the innovative scope of the chapel’s frescoes (such as the idea of connecting theInferno on the counter-façade with the Paradise on the back wall by means of the stories of the Baptist and Magdalene painted on the side walls to recall the penitential path represented by Purgatory), for which "Dante’s Comedy,“ the scholar writes, ”could not fail to offer living matter of inspiration."

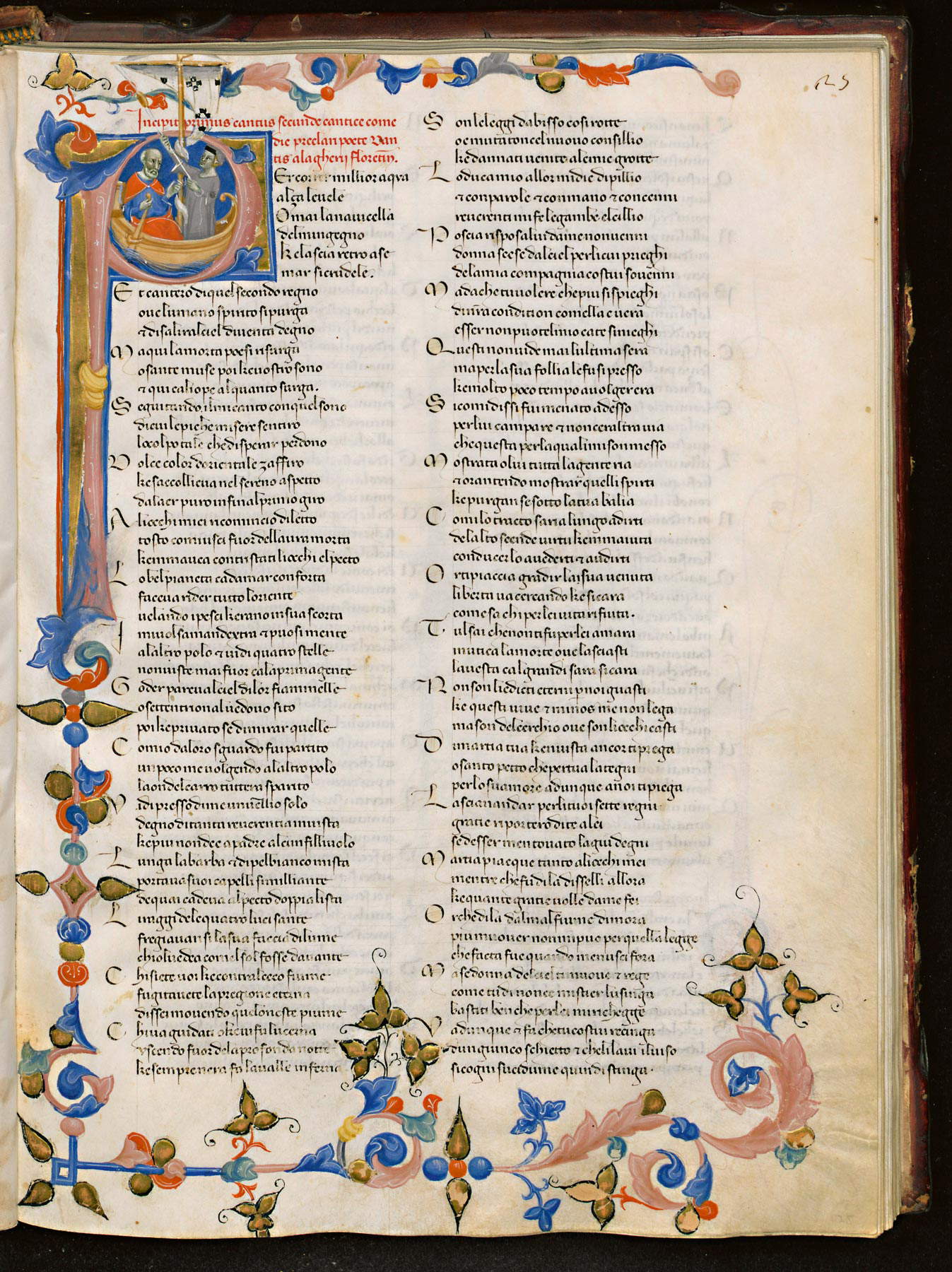

The theme of the diffusion of the Commedia in Florence in the 1930s and 1940s, as we have seen, is closely linked to the presence of Dante in Giotto’s work, and this is therefore the topic addressed by the first room of the exhibition on the ground floor. We have missed the early stages of the transmission of the poet’s masterpiece, but we know that, as early as the late 1920s, numerous copies of the Commedia began to circulate in Florence: for no other medieval author is such a widespread and remarkable circulation counted. The Commedia became a sought-after book, read by a vast and heterogeneous public, so much so that a special format was created (as evidenced by the manuscript in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana illuminated by the Master of the Dominican effigies), with the verses arranged in two columns, in a stylized script and with standardized decorations that served not to simplify the contents of the Commedia, but to enable its penetration among a wide audience. The reasons for the success, according to scholar Francesca Pasut, are to be found in the presence, in Florence, of circles intellectually close to Dante who promoted his work, in the initiation of "an early local exegetical activity (at least from the early 1930s), which was able to take advantage of the commentaries on the Commedia that had already appeared in northern Italy," and in the activity of professional copyists who, in Florence itself, tried their hand at a serial production of the poem, capable of contributing substantially to its dissemination. In parallel, a true Dante iconography developed that provided artists with a rich repertoire to illustrate the verses of the poem and enable its wider propagation.

|

| Giotto and Giotto School, Portrait of Dante (1334-1337; fresco; Florence, Bargello Museum, Cappella del Podestà) |

|

| Giotto and Giotto school, Paradise (1334-1337; fresco; Florence, Bargello Museum, Cappella del Podestà) |

|

| Ser Cichino di Giovanni de’ Giusti da Modena (copyist), Registri (1349-1357; Florence, Archivio di Stato, 19A, f. 2v: judgments against the Bianchi of 1302) |

|

| Bernardo Daddi, Astylar Cross (c. 1340; panel, 58.9 x 33 cm; Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli) |

|

| Master of San Iacopo a Mucciana, Beheading of the Baptist (last decade of the 14th century; opisthograph panel, 45 x 24 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco) |

|

| Vat copyist (copyist), Master of Dominican effigies (illuminator), Commedia (Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Pluteo 40.13, f. 25r: frontispiece of Purgatorio) |

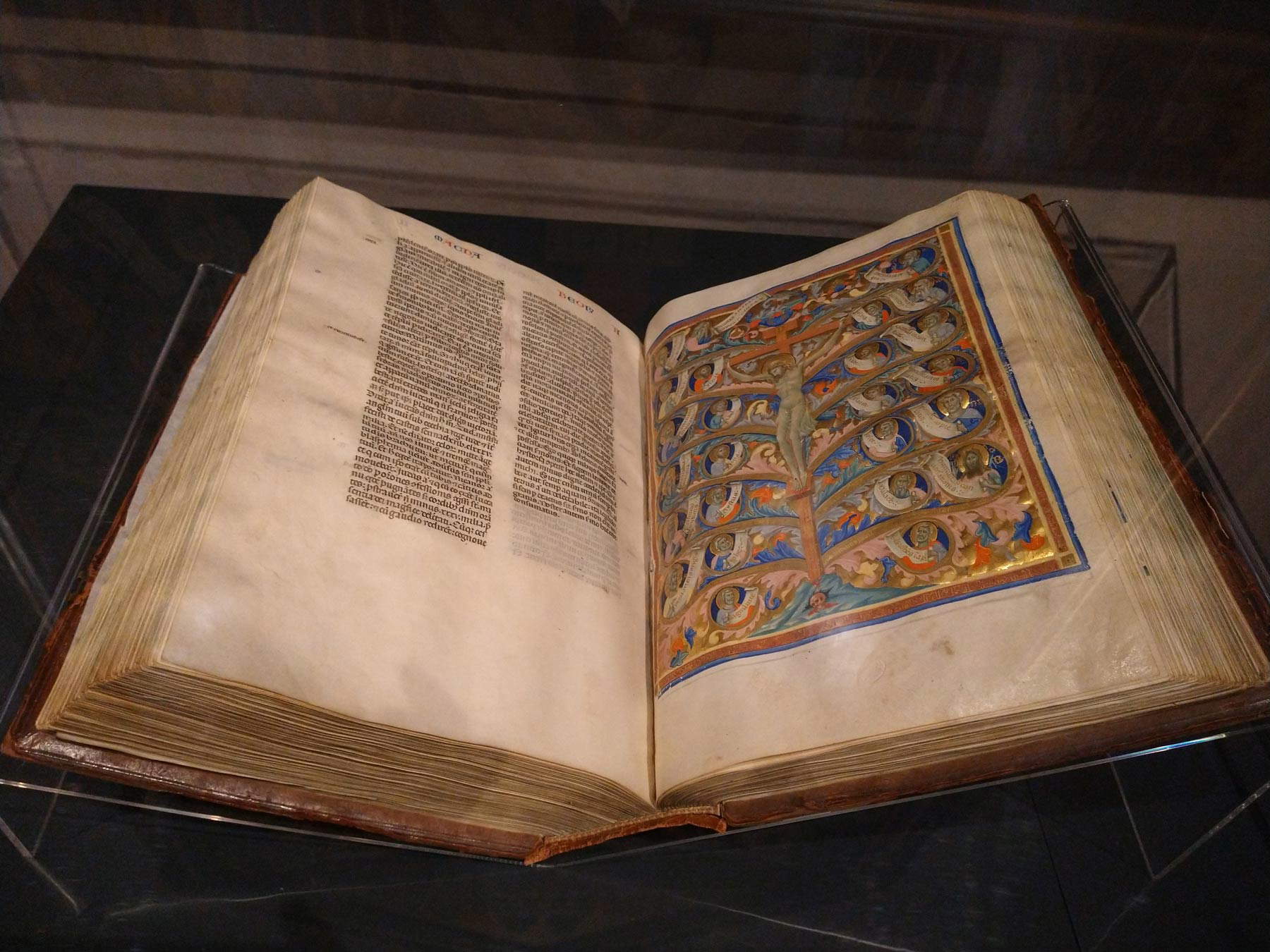

Among the “Dantesque” artists, the review presents the two who, according to the curators, had a kind of “monopoly” on the illustration of the Commedia exemplars in the second quarter of the 14th century, namely the aforementioned Master of the Dominican effigies and Pacino di Buonaguida, both illuminators and painters. By Pacino there are both works on panel, starting with the famous Lignum vitae, the largest painting in the exhibition, which comes on loan from the Galleria dell’Accademia, and illuminated works: an artist associated with the idea of a “serial production” and a “simple mode of expression, far removed from the formal complexity and high tenor on the level of content and form of the painting of Giotto and his followers” (so Sonia Chiodo: to realize this it may suffice to observe the predella compartment with the Miracle of the Mass of St. Proculus), with the Lignum vitae Pacino nevertheless succeeds in producing a complex sacred allegory, a composition endowed with strong characters of originality, which takes its starting point from the pamphlet of the same name by Bonaventure of Bagnoregio to insert the story of Christ’s life into the broader one of salvation, according to a program evidently suggested by a particularly refined mind. For the editor, the main novelty of the work lies in its hierarchical arrangement: the thematic focus is at the center (Christ crucified and the stories of his life), the “context” at the bottom (the stories of Genesis) and the final vision (i.e., Paradise) at the top. A complexity that recalls in some ways the anagogic sense of the Comedy and that prepared Pacino di Buonaguida for the illustrations of Dante’s poem itself: in the exhibition, moreover, the Lignum vitae is displayed together with the Trivulzian Codex 2139 on which Pacino executed a refined Lignum Vitae on a gilded background.

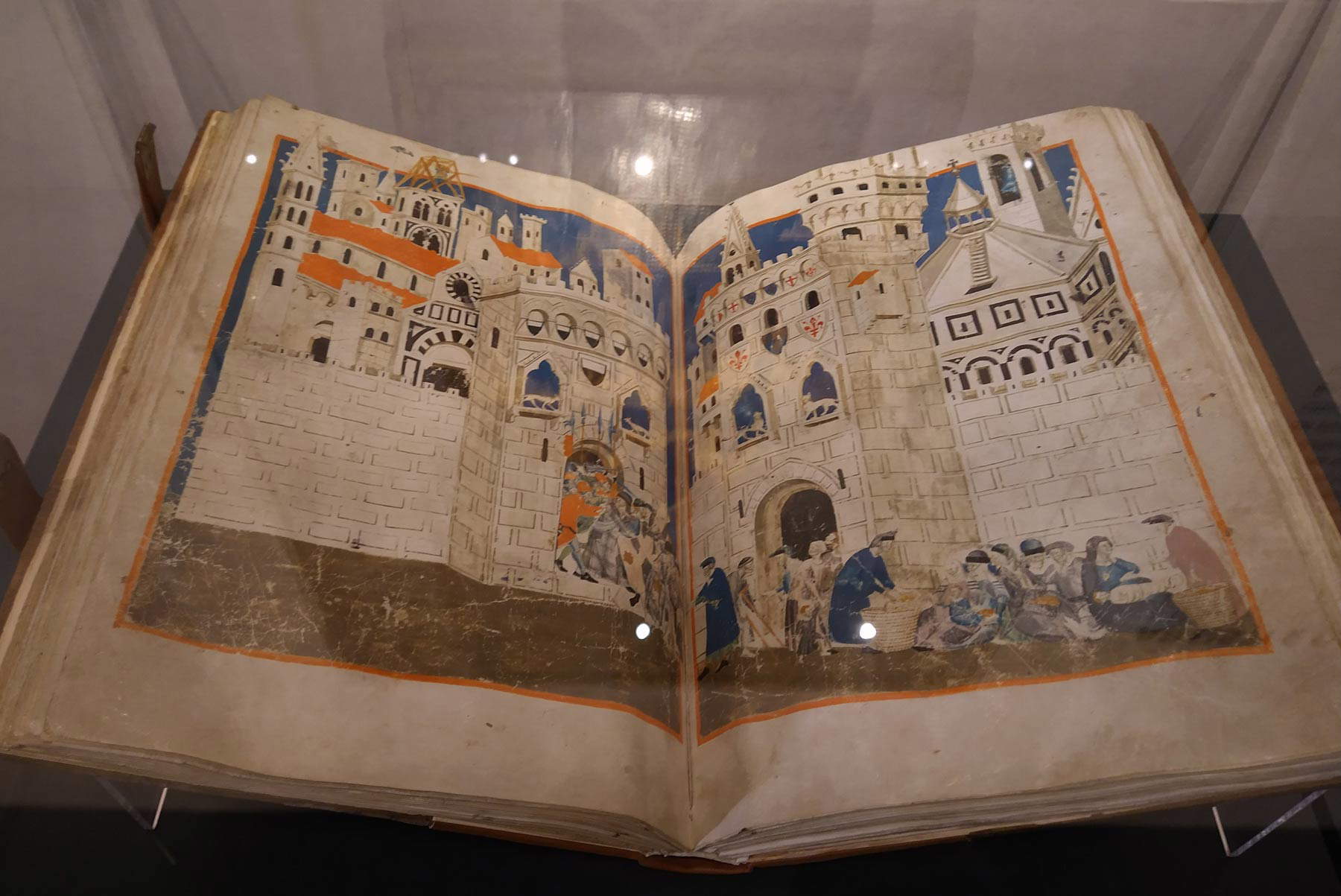

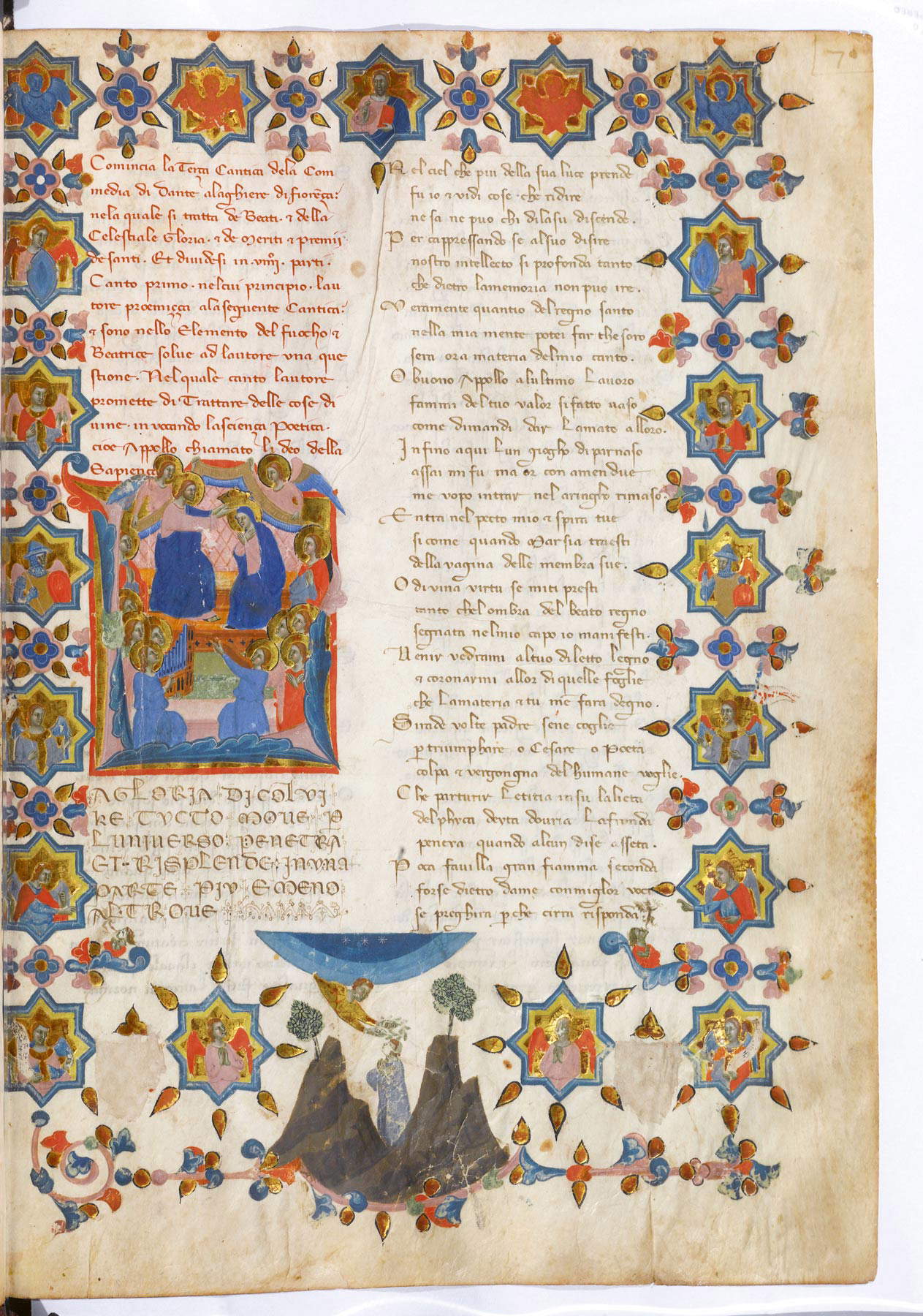

The Master of the Dominican effigies, a more solitary artist than Pacino, who was instead the head of a workshop engaged in frenetic activity, is an artist endowed, writes Sonia Chiodo, with a “more pungent verve,” attentive to reality, and also endowed with a certain irony. From the Metropolitan Museum in New York comes a fine panel of his divided into five compartments (these are scenes related to Dominican themes) and intended for individual devotion: a work with accents of naturalism and animated by a spontaneous ease suitable for better framing the Libro del Biadaiolo, that is, the list of prices of wheat and grain sold in Florence between 1320 and 1335, which, on the initiative of the merchant Domenico Lenzi, became a literary text with a high political content, since it was pregnant with considerations on the effects of good and bad government, comforted by the illustrations of the Dominican effigies by the Master himself: in the exhibition, the manuscript in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana is open on an image of the famine that hit Tuscany around 1340, namely the episode (characterized by propagandistic overtones) of Siena expelling the starving from the city walls at the height of the crisis, who are nevertheless welcomed by the magnanimous Florence, reconstructed by the Master with a realistic profile of the Baptistery of San Giovanni. Also by the Master of the Dominican effigies is the illustration of the Comedy in the Trivulziano 1080, in open review at the beginning of Paradise: an illustration that follows a typical pattern, with the initial presenting the reader with a scene (the coronation of Mary), and with further figures in the frieze (the angelic hierarchies), while at the bottom of the page Dante is observed being crowned a poet.

|

| Pacino di Bonaguida, Miracle of the Mass of Saint Proculus (c. 1325-1330; panel, 21.1 x 31 cm; Rivoli, Rivoli Castle, Cerruti Collection) |

|

| Pacino di Bonaguida, Lignum vitae (tempera on panel, 248 x 151 cm; Florence, Galleria dellAccademia) |

|

| Pacino di Bonaguida and collaborators, Bible (Milan, Biblioteca Trivulziana, Triv. 2139, f. 435r: Lignum vitae) |

|

| Master of Dominican Effigies, Final Judgment, Madonna and Child Enthroned between St. Augustine and St. Dominic, Crucifixion, Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas, Nativity (tempera on panel, 59.1 x 42.2 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

| Copyist of Vat (copyist), Master of Dominican Effigies (illuminator), Book of Biadaiolo (Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Tempi 3, f. 58r: Florence Welcomes the Poor) |

|

| Francesco di ser Nardo da Barberino (copyist), Master of the Dominican effigies (illuminator), Comedy (Milan, Biblioteca Trivulziana, Triv. 1080, f. 36r) |

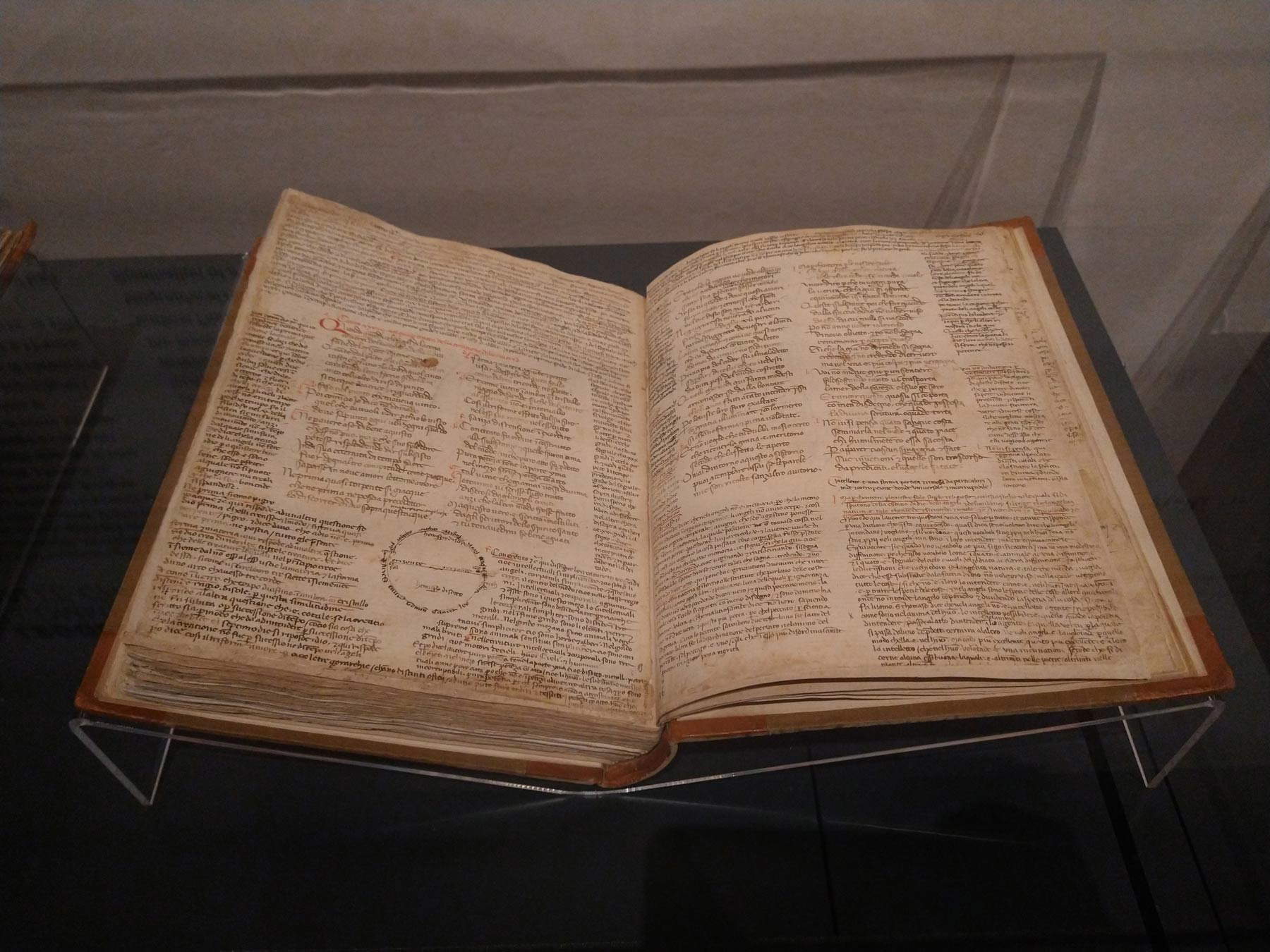

The following section goes into the merits of the success of Dante’s works in Florence in the 1430s and 1440s by focusing on theexegetical activity of the Commedia and other writings: this is further evidence of Dante’s reappropriation by his hometown. An activity, writes Andrea Mazzucchi, capable of “returning to us with vivid evidence the admiring amazement, surprise, in some cases even perplexed perplexity and bewilderment that the contiguous generations of more or less culturally equipped merchants, notaries, but also magistri and refined intellectuals must have felt when faced with a work like the Commedia, capable [....] to burst onto the cultural scene, significantly innovating the literary statutes in use and upsetting the horizon of expectation of its first readers.” Some of the most interesting examples of early commentaries include that of the Florentine notary Andrea Lancia, author of a vernacular commentary (c. 1341-1343), formally uninteresting but useful as it is among the oldest exegetical works and fundamental for reconstructing even the Dantean milieu of Florence at the time, and that of the “Friend of the Optimus” of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, opened in the exhibition on an illustration of Lucifer according to the description in Canto XXXIV of theInferno. Dante’s “rediscovery” in Florence also fostered the dissemination of the classics, with an ever-widening public becoming passionate about reading the texts of Virgil, Ovid, Lucan and other important Latin authors: in the exhibition the public will find fourteenth-century codices with Horace’sArs poetica, Ovid’s Metamorphoses and other masterpieces of classical literature.

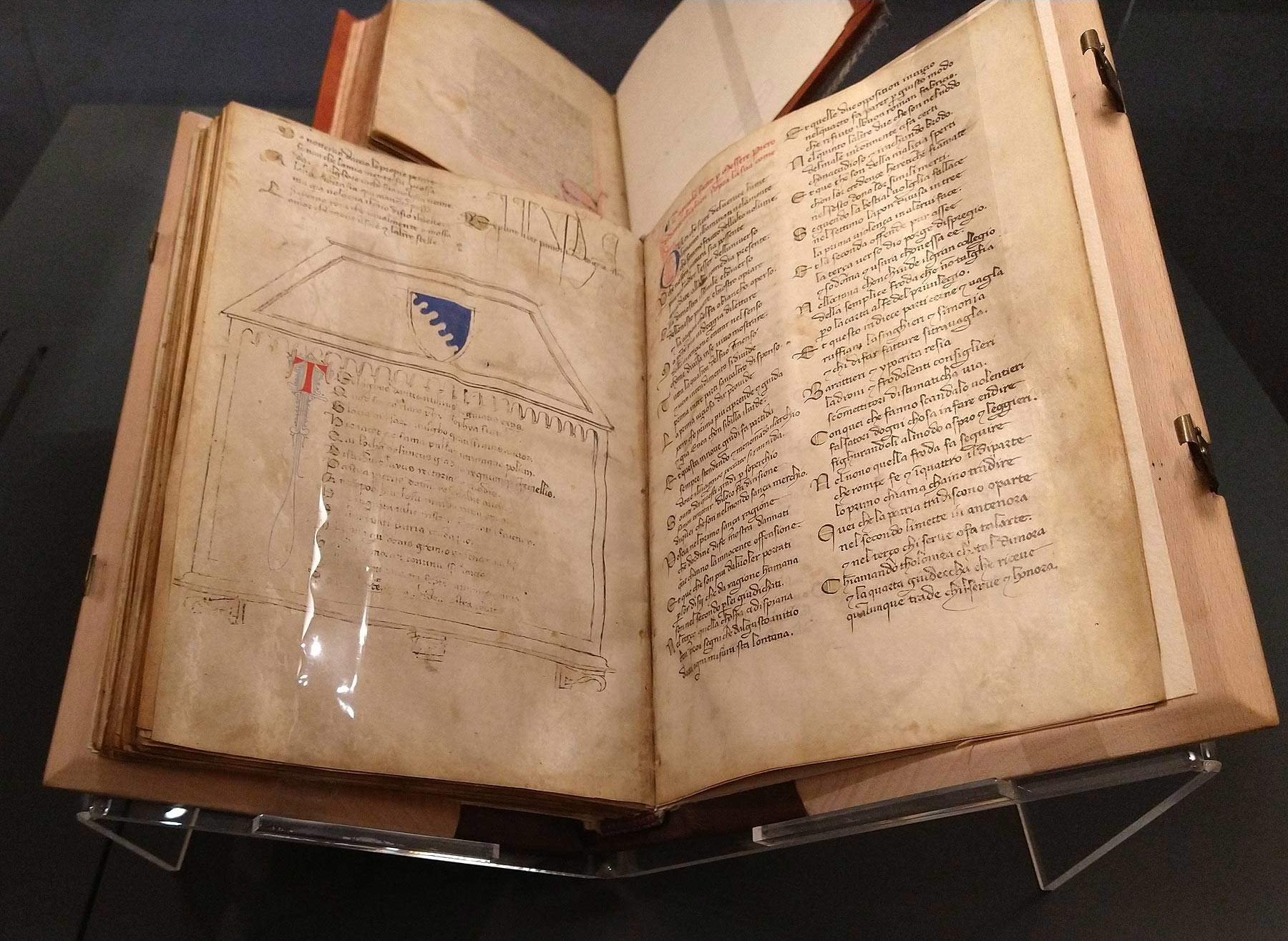

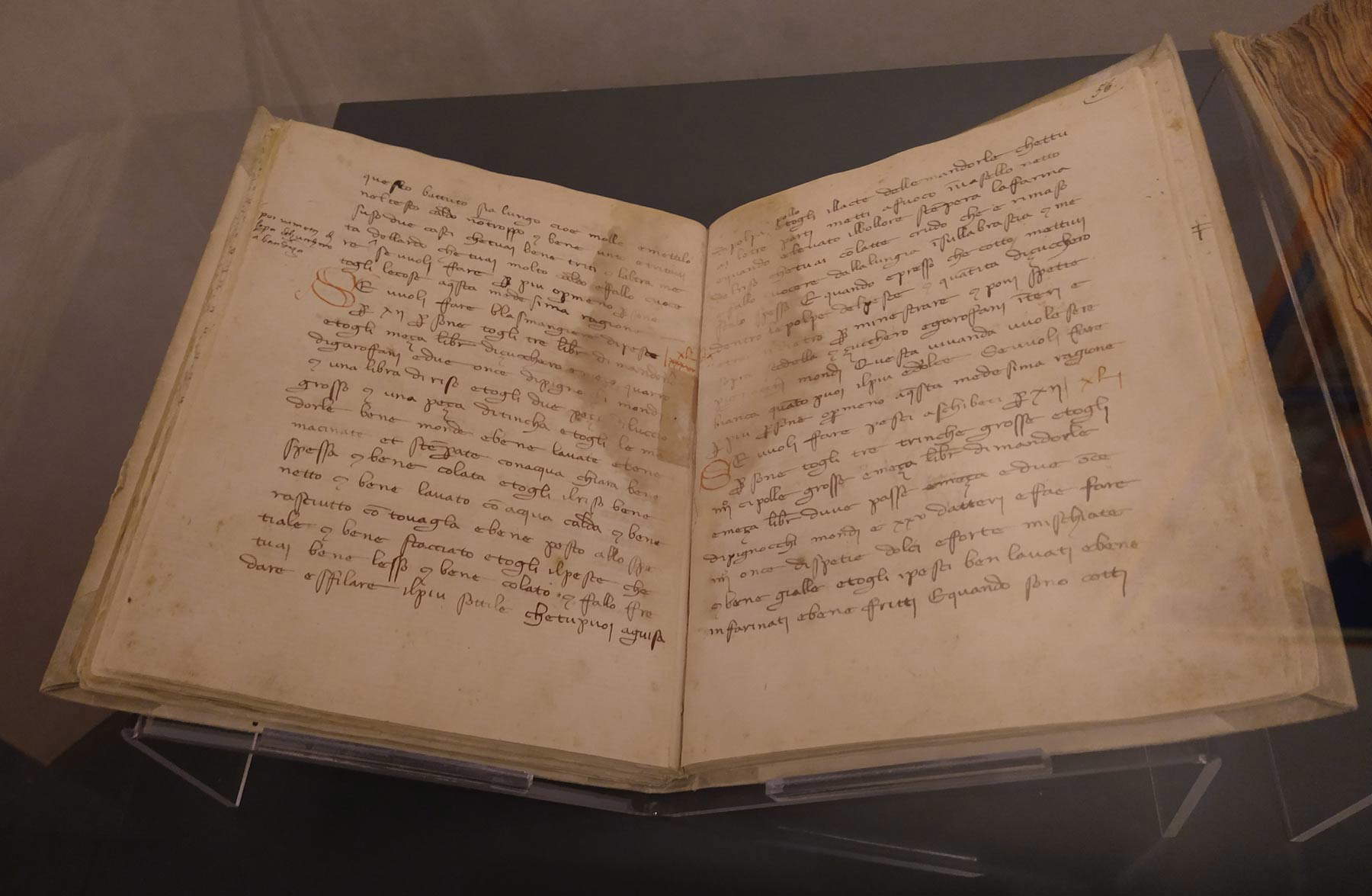

This brings us to the section dedicated to the construction of Dante’s memory, which focuses in particular on the rehabilitation of the figure of Dante with the display of Codex 174 of the Ambrosiana in Milan, containing Villani’s Cronica, and the aforementioned Toledano 104.6 with the Trattatello in laude di Dante (the codex is an autograph of Boccaccio, opened in the exhibition on the first page of the same Trattatello). Villani’s short chapter is the first known biography of Dante, “a sort of eulogy” (so Teresa De Robertis) whose narrative begins precisely from Dante’s exile, which Villani, exactly like Boccaccio, judges undeserved. The author of the Decameron, who is present in the exhibition with the work written in his own hand, suggests in the Trattatello the idea that Dante’s memory should be reparated, proposing to do so with words, recounting Dante’s life, studies and works (the codex in fact contains the Vita nova, the Commedia and fifteen songs: texts considered by Boccaccio to be particularly representative of Dante’s poetics), but letting the idea shine through that it would not have been wrong to celebrate Dante with statues or monuments. And it is interesting to see on display a manuscript from the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence in which an unknown illustrator depicts a tomb of Dante, inserted at the end of Paradiso to frame a lyric in Dante’s honor written by the Bolognese grammarian Giovanni del Virgilio (who, moreover, reiterates the topos of the “ungrateful” and “crude” homeland that brought him the “sad fruit” of exile, as opposed to the “pious” Ravenna where the poet rests). This is a codex executed in Florence: Dante had died far from his hometown (and likewise the first exegesis of his work, as well as the encomiastic activity of his figure, had originated far from Florence), and this drawing is therefore distinguished by its symbolic value, since it is as if, in a certain way, the poet’s body had returned home. The exhibition, as anticipated, closes with a section devoted to the Florentine language of the time, witnessed by simple and modest documents, even of a practical nature, such as the oldest gabella in the vernacular (on loan from the Accademia della Crusca) and also by a curious cookbook filled with rich recipes: works that give an account of the differences between the literary language and the one instead practiced in everyday life, and thus allow us to delve into the most vivid and everyday expression of the language of the time.

|

| Andrea Lancia (copyist), Commedia commentata (Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, II.I.39, f. 185v) |

|

| Andrea Lancia (copyist), Commedia con il commento dellAmico dellOttimo (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M.676, f. 47r: Lucifer at the bottom of Hell) |

|

| Ovid’sArs Poetica (Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Pluteo 36.5) |

|

| Giovanni Boccaccio (autograph), Life of Dante and collection of works of dellAlighieri (Toledo, Archivo y Biblioteca Capitulares, Zelada 104.6, f. 1r: Trattatello in laude di Dante) |

|

| Manuscript with texts from Dante (Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Conventi Soppressi C.3.1262 f. 101v: Dante’s tomb and epitaph) |

|

| Book of culinary recipes (Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana, 1071, f. 55v) |

With Honorable and Ancient Citizen of Florence, the Bargello attempts a singular, complex, in some ways even difficult operation, which occupies a very special place in the framework of the events for the seven hundredth anniversary of the poet’s death: it is an exhibition that, in essence, offers visitors a profound historical, cultural, political, and in a certain way even social insight into early fourteenth-century Florence, according to a multidisciplinary perspective (and so, after all, it could not but be given the ambitions of the review). It is an exhibition where the works of art are objectively few, but which is not repelling to the public, given that the organizers have intervened with apparatus capable of guiding even visitors well among the many codices that have come on loan from various important institutions, and have even enriched the experience with audios that play Dante’s verses read by Pierfrancesco Favino. It was not easy to capture the public with an exhibition that could be perceived as an in-depth study for specialists: in fact, beyond the undisputed scientific value, the organization was evidently aware of the popularizing value of an event that traced the history of Dante’s rehabilitation in his city.

An exhibition that recognizes and recounts the way Florence treated Dante is, meanwhile, an exhibition that is anything but obvious: the public will get to know a good part of the reasons for Dante’s success, and if we still read the Divine Comedy today, the reasons are also to be found among the exhibits. And perhaps it is also the best way to remember the poet on the eighteenth century, also to reason about how current the content of his texts and human experience is: the way the exhibition has been constructed invites reflections that go even beyond the illuminated pages and painted surfaces. It was said at the beginning that this is a very political exhibition. The poet had not been able to return to his city in person: he returned there in the form of a book. And now he returns to it in the form of an exhibition.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.