When we enter the hall of a museum, we usually expect to see a series of paintings, all hung up and ready to be admired. However, we would never think that we would also be able to look at the back of these works. And that is precisely why, at first glance, the exhibition Abscondita. Secrets Unveiled of the Artworks leaves one a little taken aback. Hosted inside the Museo Civico in Bassano del Grappa until Nov. 5, this exhibition consists only of works seen ... from behind. The works in the picture gallery and the depository, in fact, have been patiently turned and analyzed, and have brought to light anecdotes, stories related to the artists and collectors of the city, mysteries that in part have been solved but about which we still wonder. Behind these works a real world has been discovered.

An exhibition project of this kind is unprecedented: never had an exhibition of only retri. In fact, the idea behind it is not entirely new, and has its roots in the distant seventeenth century. Already between 1670 and 1675, the Antwerp painter Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts (Antwerp, c. 1630 after 1675) painted in oil a canvas, now housed in the National Museum in Copenhagen, showing just the back of a painting. The artist recreated, with meticulous detail, the texture of the canvas as seen from behind: the support, the nails, the inventory card, devoting for the first time in the history of art so much attention to something that had not been considered worthy before. Art, then, no longer just as a representation of a scene or subject, but as a medium that thinks about itself and its hidden structures. A high-resolution reproduction of this Gijsbrechts canvas is now on display in the Bassano exhibition, precisely to highlight the precedent that led allidea. Abscondita ’s goal is precisely the same as that of this seventeenth-century canvas: while the work is evidence of a subject, the back of it becomes evidence of the support, the object and its history. As Chiara Casarin, the museum’s director and curator of the exhibition, argues: Crossing the threshold of the visible, of what is officially allowed, by crossing the canvas or the panel we enter a world that is still almost completely obscure. If in front we find inventions, behind is a world of inventories.

|

| Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts, Trompe l’oeil. The Reverse of a Framed Painting (1670-1675; oil on canvas, 66.4 x 87 cm; Copenhagen, National Museum Copenhagen). The exhibition features the reproduction |

The selected works number about a hundred and range from the Late Middle Ages to the 20th century, including artists such as Tiepolo, Canova, Hayez, Ciardi and Sironi. Showing unknown and hitherto ignored worlds, these works induce the viewer to confront without being subjected to the rules of pictorial composition. These retros appeal to our curiosity, our desire to know something that would otherwise be reserved only for scholars and insiders.

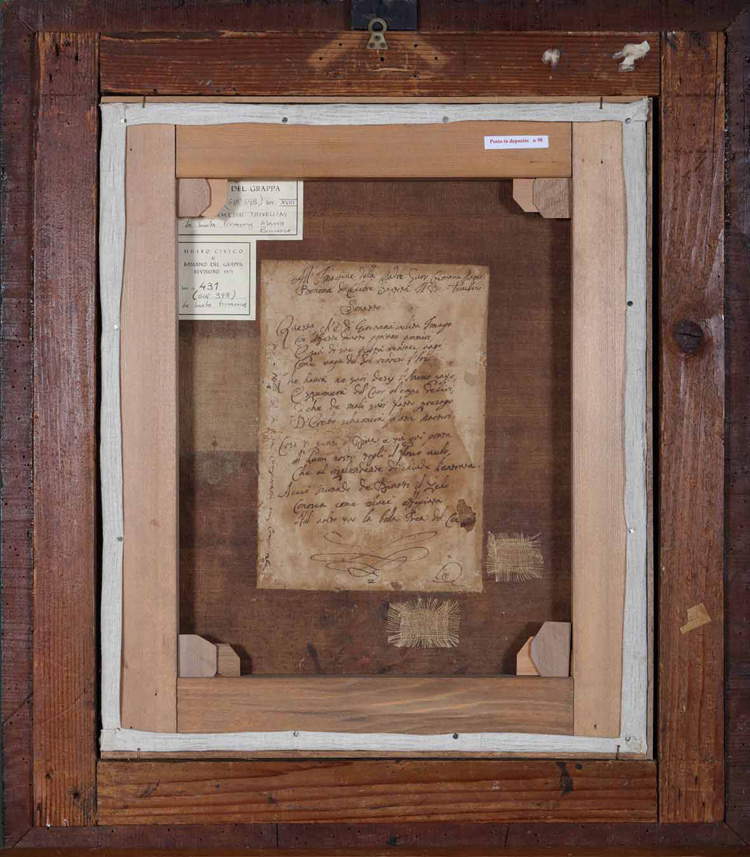

On the backs of the works there is crucial information of impressive richness. Inventory and exhibition participation cards reconstruct the history and movements of the work. Codes, numbers and acronyms in different colors trace how the work came to be part of the museum collection, participation in some auction, and the families of the city who owned and donated it. Attributions, denials, re-attributions; artists’ names written, crossed out, rewritten with a few corrections show the constant study behind each work. Behind the works there may also be descriptions, newspaper articles and dedications, as in the case of the sonnet on the back of the work La Beata Giovanna Maria Bonomo by Francesco Trivellini (Bassano del Grappa, 1660 1738) and which is dedicated to her.

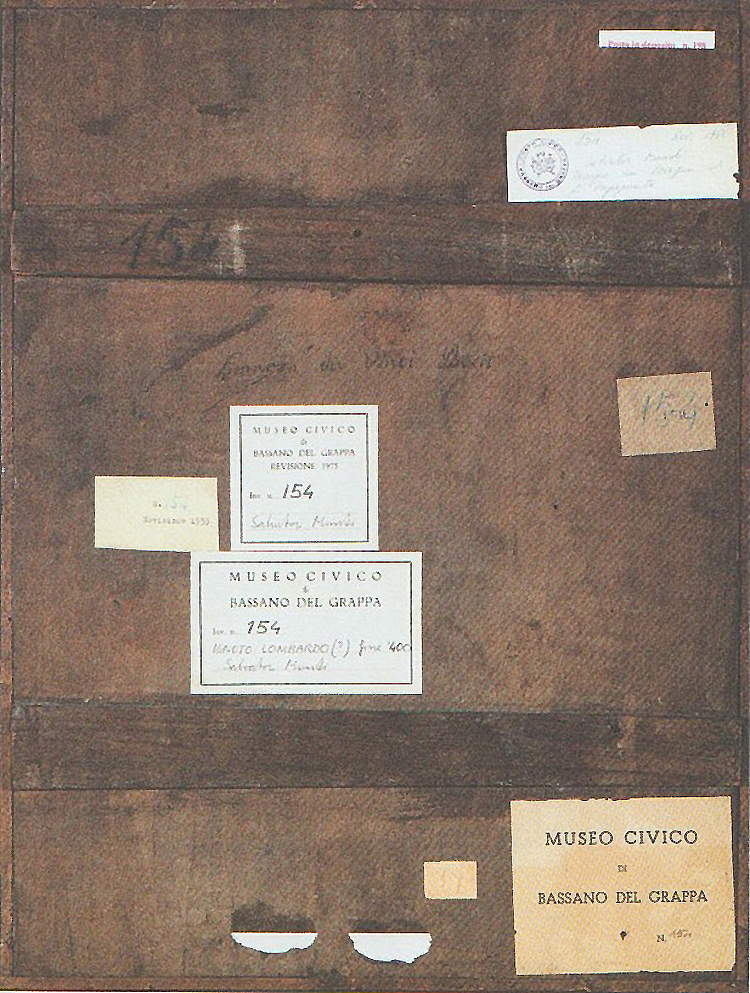

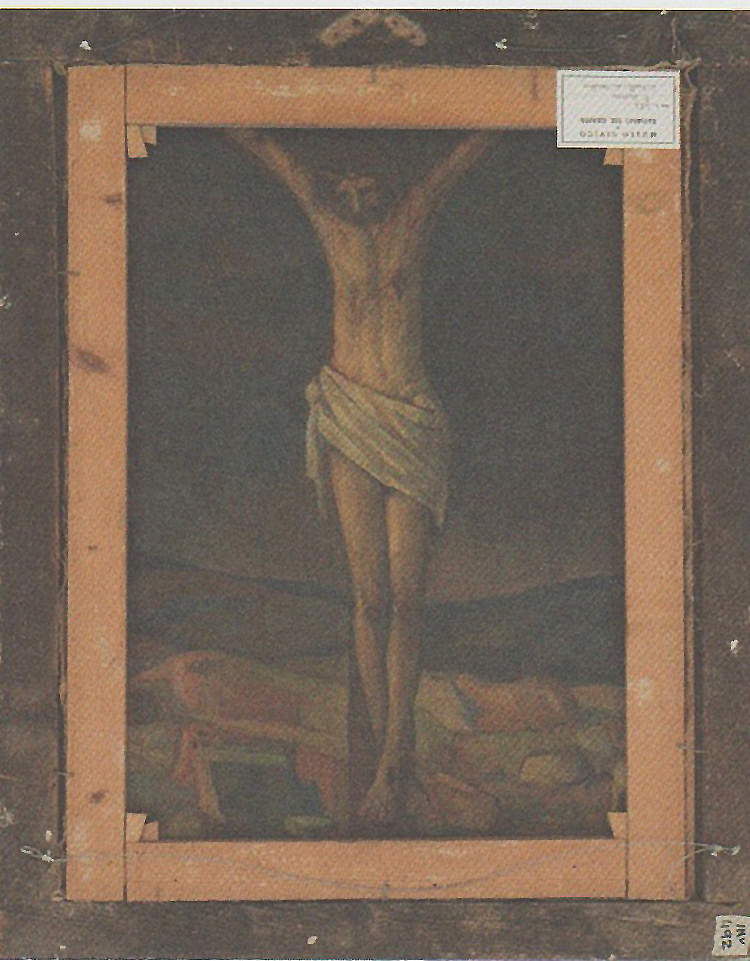

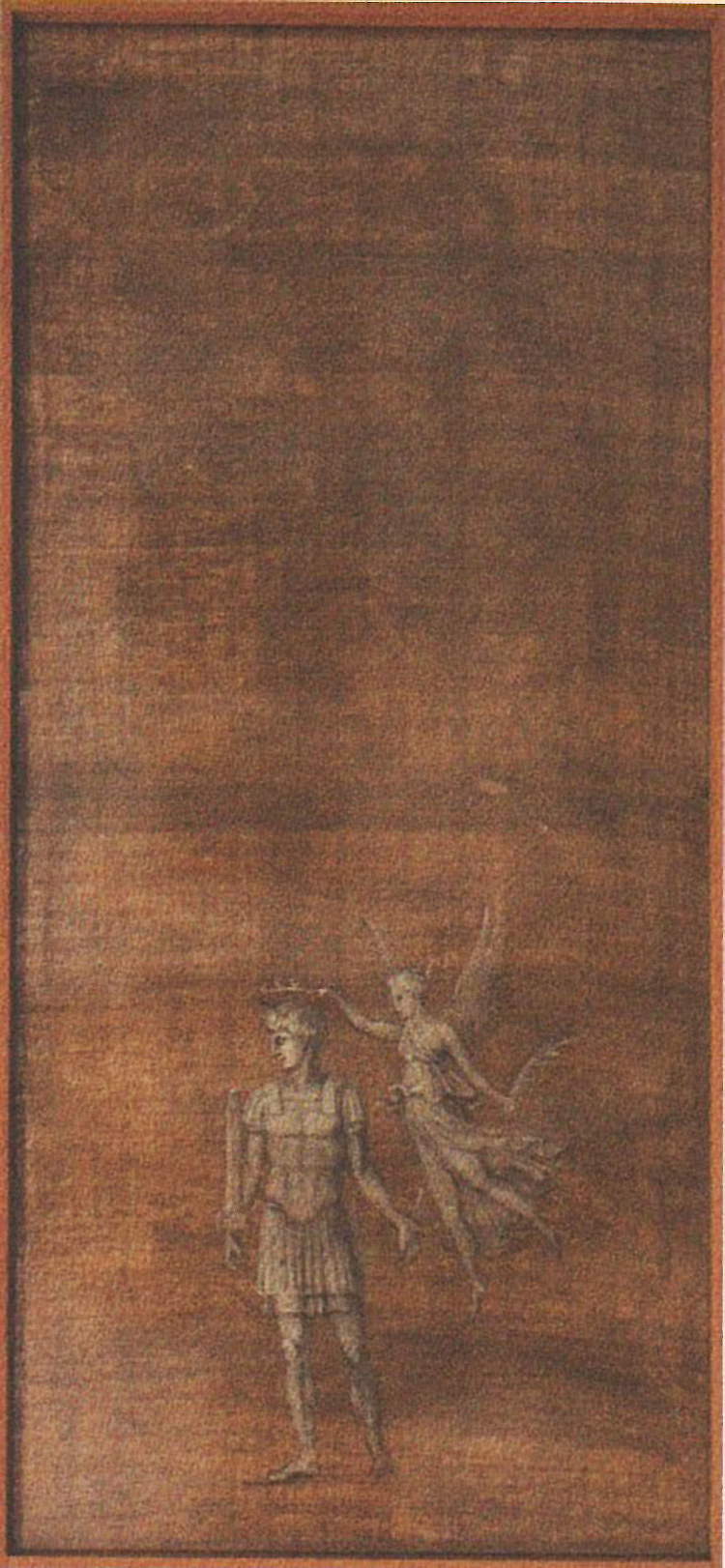

Signatures are often found on the back of works, as in the case of the Portrait of Count Francesco Roberti, which bears the signature of its author, Francesco Hayez (Venice, 1791 Milan, 1882). And it happens, at times, that these signatures bring havoc and mystery. Such is the case with a Salvator Mundi that bears the words Leonardo da Vinci pinxit on the back but was painted by an unknown 15th-century artist who was already aware of Leonardo’s genius. It may happen to find behind a work another work, something that was discarded by the author, an afterthought, a mistake; for example, the Ritratto di vecchio by Pietro Roversi (Faenza, 1908 Bassano del Grappa, 1992) on the back has an interesting canvas of an upside-down crucifix. Also on display are two monochromes by Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 Rome, 1822) in the back of which figures are depicted, five dancers in one case and a male figure in the act of being crowned in the other; subjects that echo the graphic and pictorial characteristics of the master’s other studies and could certainly be the protagonists of a front. Also interesting are the drawings by Mario Sironi (Sassari, 1885 Milan, 1961) displayed in this selection of works and part of a corpus that came to the Bassano Museum in 2011. Many of the sheets owned by the museum are drawn, pinned and painted on both sides and especially show the results of the last two decades of the artist’s work.

|

| Francesco Trivellini, La beata Giovanna Maria Bonomo, verso (18th century; 78 x 69 cm; Bassano del Grappa, Musei Civici) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Portrait of Count Francesco Roberti, verso (1819; 56 x 48 cm; Bassano del Grappa, Musei Civici) |

|

| Ignoto lombardo, Salvator Mundi, verso (15th century; 53 x 40 cm; Bassano del Grappa, Musei Civici) |

|

| Pietro Roversi, Portrait of an Old Man, verso (1936; 92 x 75 cm; Bassano del Grappa, Musei Civici) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Transporting the Body of Orazio Nelson to the Ground, verso (c. 1805; 88 x 172 cm; Bassano del Grappa, Musei Civici) |

The fascinating history of the works with this exhibition is revealed and becomes within everyone’s reach, making the visitor feel like a participant, like a keeper of the museum’s secrets. It is enough to lay a bare canvas at the foot of a wall, a little tilted, and stop and look at it, wrote Italo Calvino in The Squaring, to realize how ungrateful we are who have eyes only for what is carried, the painting, and not for what it is meant to carry: the canvas, its frame, the wall that holds them, the ground on which the wall rests.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.