by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 11/04/2019

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "The Child Artist. Childhood and Primitivism in Early 20th Century Italian Art" in Lucca, Fondazione Ragghianti, from March 17 to June 2, 2019.

When artists painted like children. Infantilist primitivism in early 20th century Italian art.

In an enterprising exhibition that was mounted at the Mole Antonelliana in Turin in 1990 and was entitled Italian Expressionism, curators Renato Barilli and Alessandra Borgogelli set themselves the stated goal of “bringing to light a kind of submerged continent of which, as happens in the geographical reality from which the metaphor is taken, scattered nuclei, isolated peaks, interrupted plateaus survive.” the submerged continent that Barilli and Borgogelli intended to resurface and whose existence they wanted to emphasize was, precisely, that ofItalian expressionism. A label that had been used for convenience, in order to bring together under a single category a series of different experiences and personalities, and which were nevertheless united by the desire to attempt another path than that of painting linked to the logic of mímesis. It was a label borrowed from the trends that were emerging simultaneously in France and in northern Europe, although the Italian Expressionists were separated from their foreign colleagues by rather marked differences: first of all, the heterogeneous character of the Italian Expressionists, who never united in groups (as happened for the artists who founded Die Brücke in Dresden or Der blaue Reiter in Munich) or never had a place of reference, and the nature of their primitivist tensions. One thinks of what used to happen in the Paris or Munich of the early twentieth century, when the fascination with non-European cultures decisively directed the interests of expressionists from the German area as well as those of the Cubists. On the contrary, in Italy, the search for archetypal forms had, if anything, some tangency with the experiments of a Paul Klee who neglected nothing in his investigation of the origins of art (and “at the origins of art” was also the title of a recent exhibition in Milan, curated by Michele Dantini and Raffaella Resch, which made an accurate investigation of the artistic and historiographical sources at the basis of the Swiss artist’s figurations), and was nourished by a renewed interest inmedieval art and in the artistic expressions of children.

The subject of recent studies, these events in Italian art at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are enriched by a new contribution: the exhibition L’artista bambino. Infancy and Primitivism in Early 20th Century Italian Art, set up at the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca until June 2, 2019 and curated by Nadia Marchioni. The Lucca exhibition aims to provide new contributions in order to frame in a more in-depth way the contribution that the universe of childhood provided to Italian art of the early 20th century: and for an exhibition with this objective there could not have been a more appropriate venue, since Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti (Lucca, 1910 - Florence, 1987) was responsible for some significant research on the subject, which had the merit of recognizing the importance of certain impulses for Italian artistic culture at the beginning of the 20th century, of clarifying the connections between infantile art, popular or spontaneous art and the art of the so-called primitives (the artists from the thirteenth to the early fifteenth centuries), and of relating to the painters of the Apuan area those “proposals that, albeit within the pronounced culturalism that marks the period of the Secessions, form a well identifiable trellis.” an ensemble of artists who, “without being either a cenacle or a group,” remained “in a circle in the period before 1914, and the exchanges are stated.”

Critics have long noted the importance of the infantilist component in early twentieth-century art: a component that played a significant impactful role in the attempt, by a vast plethora of artists, to return to the roots of figuration, and which added to (and in some cases, as will be seen, blended with) the recovery of artists who worked before the Renaissance. The reconsideration of the artistic experiences of children fit well with the aims of an art that privileged expression over representation (and for these reasons, the interest in childhood fascinated most of the most innovative artists of the time, from Klee to Kandinsky, from Gabrielle Münter to Franz Marc), and if one considers the fact that at different cultures there is no clear distinction between child and adult art, it follows that infantilist instances were also consensual to the researches of those who looked with lively transport at the artistic manifestations of the most distant populations. The result was the flourishing of exhibitions dedicated to children’s art, the study of the peculiarities of the drawings of the youngest children and their way of expressing themselves through signs and colors on paper, the willingness, manifested by several artists, to collect works made by children (an example of this was the well-known Blaue Reiter almanac promoted by Kandinsky). Basically, there was an awareness, enunciated more or less explicitly according to individual cases and personalities, that the limits of the concept of art had to be extended, and to work in this direction it was necessary, as a consequence, to also extend the audience of subjects to be evaluated, especially if the main purposes of the experiments included going back to the primal sources of artistic expression.

|

| A room of the exhibition L’artista bambino at the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca |

|

| A room from the exhibition L’ artista bambino at the Ragghianti Foundation in Lucca |

|

| A room of the exhibition L’ artista bambino at the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca |

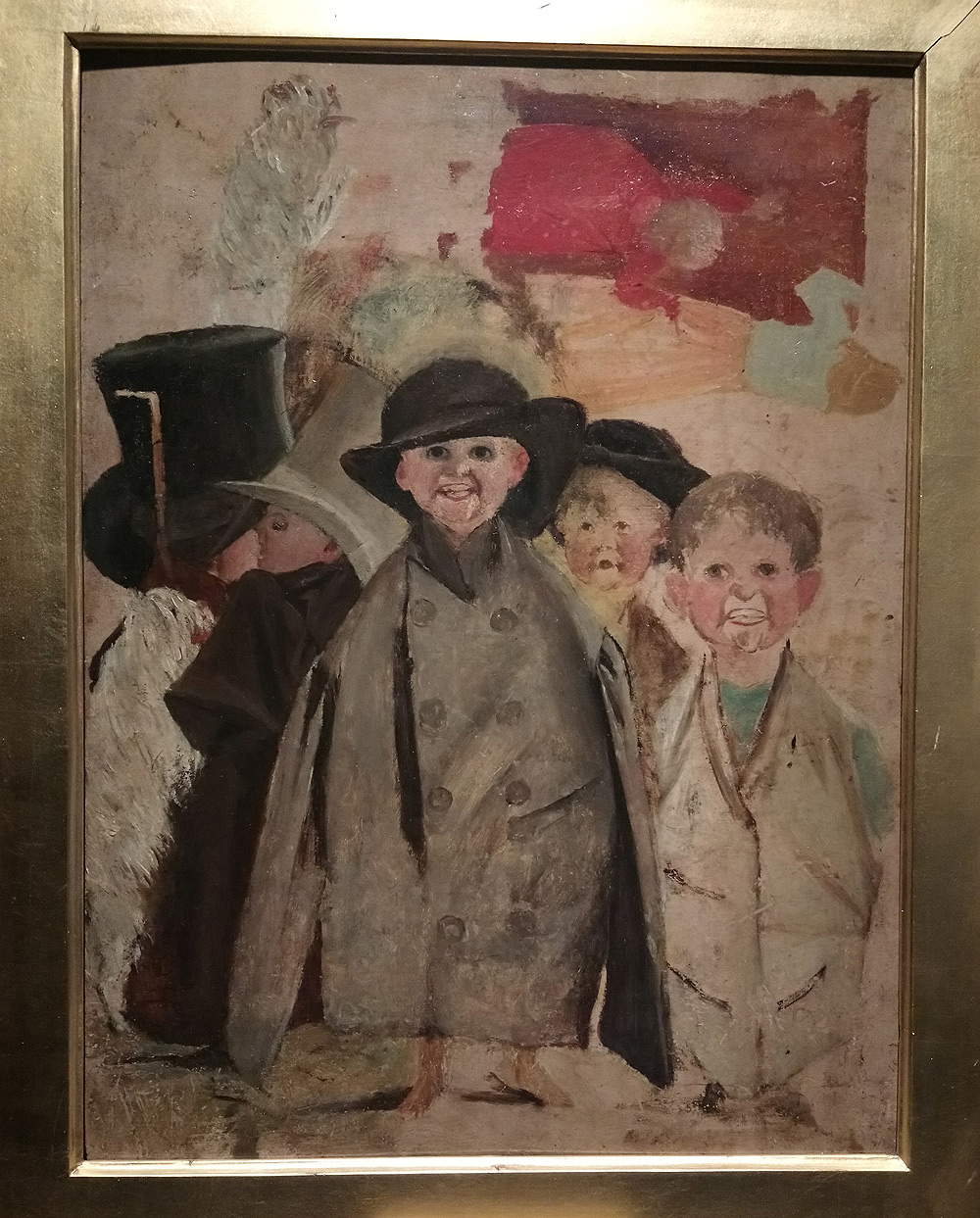

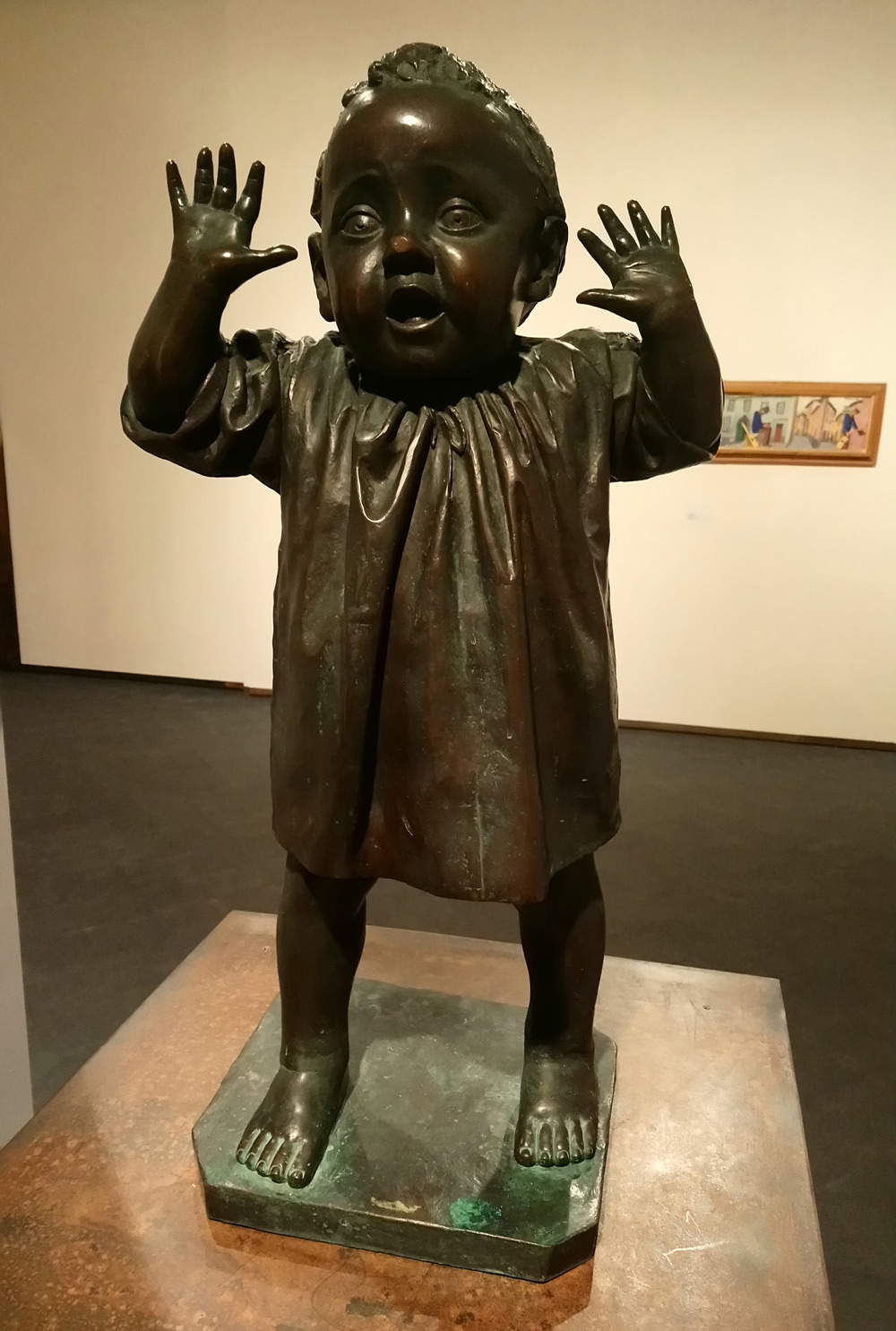

Interest in childhood began to emerge, however, even before many of the protagonists of the Expressionist season were born, and in this sense one of the purposes of the Lucca exhibition is also to broaden the view in order to identify, at least in Tuscany, what the necessary premises might have been: the first two sections thus serve as a historical and theoretical introduction. The first attentions of artists to the world of childhood date from shortly after the mid-nineteenth century: While Gustave Courbet can be attributed with a sort of forerunner role in France, in Italy the primacy belongs to Adriano Cecioni (Fontebuona, 1836 - Florence, 1886), a realist artist who participated in the theoretical elaboration of the painting of the stain, who was also among Courbet’s main Italian admirers (indeed, Cecioni was probably the artist in Italy who came closest to the ideas of the great Frenchman) and who had a very unfortunate biographical event. The opening of L’artista bambino is entrusted to a trio of Cecioni’s works(Ragazzi masquerading as grown-ups, Primi passi and Ragazzi che lavorano l’alabastro) that confront the audience with the vivid emotion that the Tuscan painter and sculptor must have felt when approaching anything involving children. Of children, Cecioni admired their spontaneity and freedom (this is perceived in Ragazzi mascherati da grandi, a painting in which, the curator points out in her catalog essay, “the author seems to want to denounce a sort of short circuit between adulthood and the childish universe: children playfully imagining future life are reflected in the eyes of the painter, who returns as a child and portrays them with an unprecedented formal language from the sprezzature so exhibited as to almost evoke the much more modern masks of Ensor”) as well as the expressiveness and ability to feel much more intense and sincere sensations than those of adults(First Steps is an exemplary work). It is clear that Cecioni’s imagery was heavily conditioned by his personal vicissitudes, and these connections are well underscored in Silvio Balloni ’s essay, which, through an examination of excerpts from certain letters Cecioni sent to his wife Luisa between 1872 and 1884 (unpublished and published for the occasion, another interesting achievement of the Lucca exhibition), identifies the matrix of his lively involvement on childhood themes in what is described as an “exasperated and wearing filial affection,” and which we imagine increased to the threshold of morbidity after the artist lost his young daughter Florina in 1870, with the consequence that all his attentions turned to his other son, Giorgio: the artist, when away from home, wrote letters filled with the most trivial, repeated and futile recommendations, and demanded that his wife inform him daily about the state of his little son’s health, even to the point of considering the non-receipt of a letter a kind of affront.

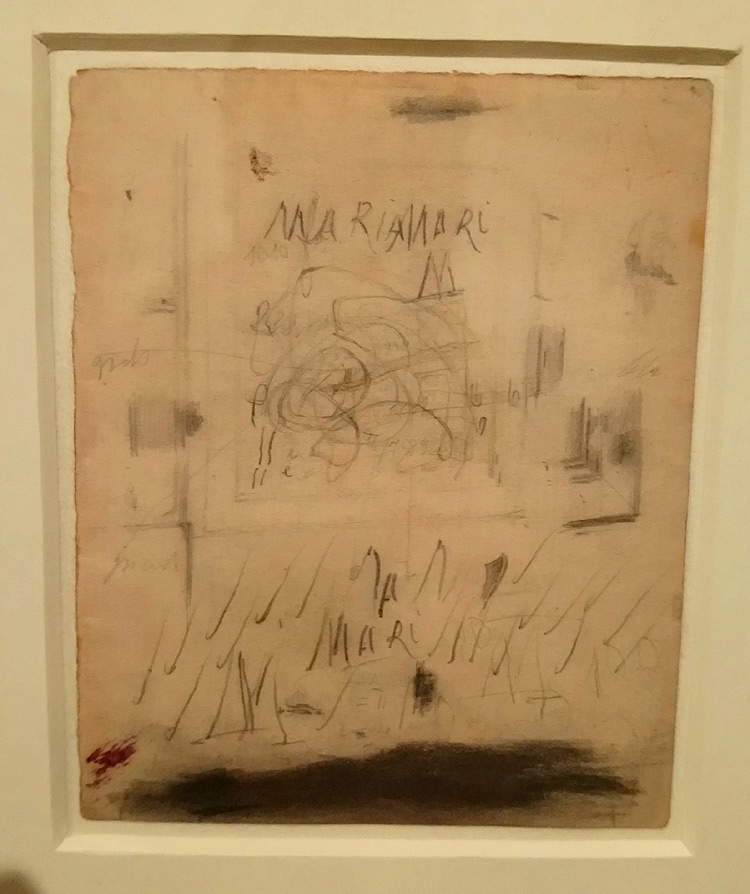

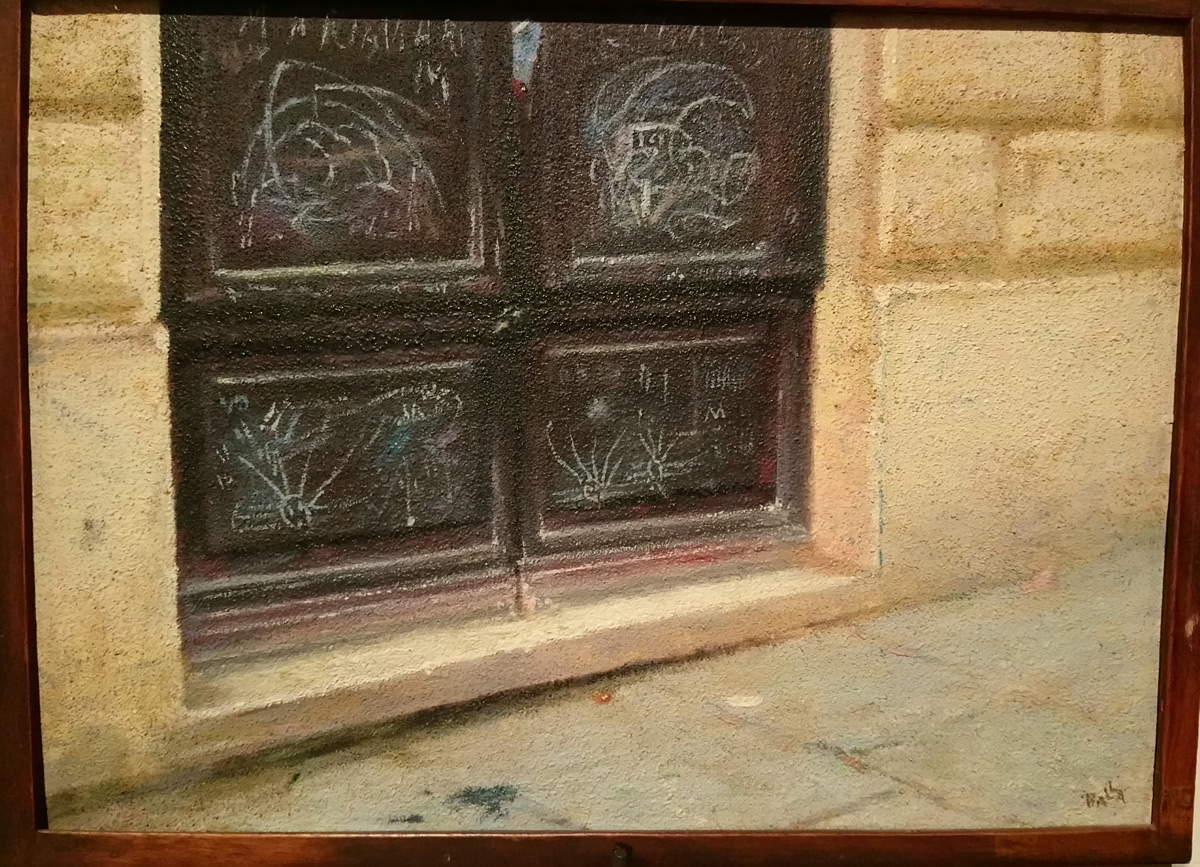

Theoretical preambles can also be traced back to the 1980s: the publication of an important booklet by archaeologist and art historian Corrado Ricci (Ravenna, 1858 - Rome, 1934), not yet 30 years old at the time, which collected the results of a conference held the year before in Bologna and Florence, dates back to 1886. Ricci, with his small volume entitled L’arte dei bambini (Children’s Art), set himself the goal of identifying “the norm that guides children’s art,” arriving at the conclusion that young children do not represent reality as they see it, but as they perceive it (and consequently each child, Ricci emphasized, also portrays “what interests him most, what he most desires”): their artistic manifestations are therefore not imitative, but descriptive. For example, what Ricci called the “law of the personal integrity of the individual” applies: if one thinks of the human figure, the child is aware of the fact that human beings are endowed with two eyes, a nose, a mouth, two arms and two legs, and no matter what position the figure takes in the drawing (the typical case being a man or a woman turned to the side), in the child’s drawing all the anatomical details will be exposed to the view of the relative. Corrado Ricci’s essay was taken into consideration by Vittorio Matteo Corcos (Livorno, 1859 - Florence, 1933), who with his Ritratto di Yorick (a friend of the painter) took up the writing almost slavishly, since the latter opened with a description of a walk Ricci had taken under the porticoes of Bologna, coming across some graffiti made by children (and Corcos himself includes some of them in his painting). The pioneering nature of Ricci’s publication is emphasized by Lucia Gasparini in her catalog essay: Children’s Art was the result of the analyses that the scholar made after collecting hundreds of children’s drawings, which he approached without prejudice, and which allowed him not only to focus attention on the creative process rather than the result (thus anticipating much of twentieth-century art), but also, Gasparini points out, to mature “a perception, albeit still vague and not clothed in scientificity, of what would instead be a high road in the years to come in both the psychoanalytic and psychiatric fields, that is, the consideration of child drawing as a very valuable diagnostic tool” (child art, for Ricci, “is sometimes revelatory”). The Ravenna scholar’s reflections led to an increase in studies on the subject, and several artists also caught its appeal: the example of Corcos has been given, but Giacomo Balla (Turin, 1871 - Rome, 1958) also grappled with children’s art, as evidenced by his Fallimento, presented in the exhibition through a sketch and a preparatory note that provide clear evidence of the care Balla lavished in his attempt to reproduce the scribbles traced by children on a door of a store in Via Veneto in Rome.

|

| Adriano Cecioni, Boys Masquerading as Grown-ups (oil on panel, 32.5 x 24.3 cm; Florence, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Adriano Cecioni, First Steps (c. 1868; bronze, 73 x 35 x 26 cm; Viareggio, Matteucci Institute) |

|

| Adriano Cecioni, Boys Working Alabaster (1867; oil on canvas-backed cardboard, 39.7 x 47.8 cm; Milan, Pinacotecca di Brera) |

|

| Vittorio Matteo Corcos, Portrait of Yorick (1889; oil on canvas, 199 x 138 cm; Livorno, Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori) |

|

| Giacomo Balla, Appunti dal vero per il quadro fallimento (c. 1902; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

|

| Giacomo Balla, Bankruptcy (c. 1902; sketch, oil on panel, 23 x 31 cm) |

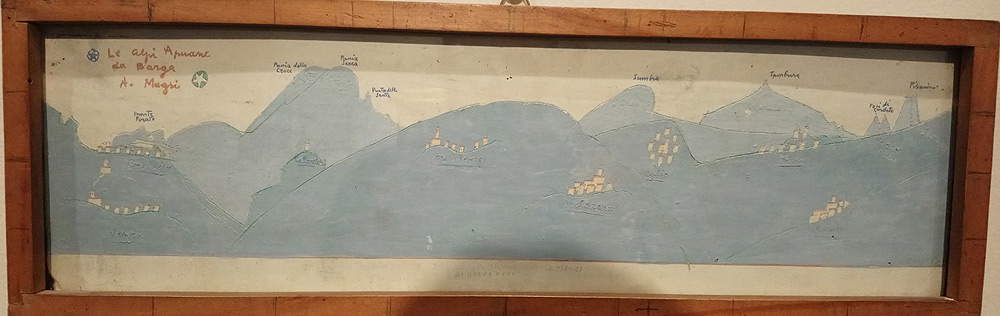

The “Tuscan-Apuan” line is the protagonist of the third section of the Fondazione Ragghianti’s exhibition: in particular, it is around the figure of Alberto Magri (Fauglia, 1880 Barga, 1939) that the exhibition focuses. The centrality of Alberto Magri in the sphere of early twentieth-century infantilist painting has been emphasized recently, and in this sense it is worth recalling the work of scholars such as Francesca Sini, Gianfranco Bruno, Umberto Sereni, Pierluca Nardoni, Raffaella Bonzano and others who have contributed to the recovery of this essentially isolated artist, but in whose poetics Nardoni, in one of his 2015 essays, identified the maximum example of that Tuscan primitivism that conceptually referred back to the reflections of one of the most important artists of the mid-nineteenth century, Luigi Mussini, according to whom talking about “childhood” also meant going back to the childhood of Italian art, that is, to medieval primitives. It was a matter, Barilli would explain in another of his essays, of “constructing a new future by dredging up energy from a more distant past,” a past in which the intentions of imitation of the real were not yet so stringent as to pressingly condition those who created works of art (it was believed, in essence, that the art of primitives was freer and in a certain sense closer to that of children). Magri, of Pisan origin, had undertaken scientific studies at the Normale in Pisa, stayed for some time in Paris in the early twentieth century, in his early twenties, worked as an illustrator and as a writer of satirical cartoons, was a cultured artist who studied antiquity, and soon chose to settle in Barga, his parents’ home village, where he used to spend his summers. Evidently, Nadia Marchioni speculates, Pascoli’s readings contributed to his choice of his chosen homeland: his return to the places of his childhood was seen as a kind of dedication to Giovanni Pascoli’s voice of the Fanciullino (“you are the eternal child, who sees everything with wonder, everything as if for the first time. Man sees things, internal and external, not as you see them: he knows so many details that you do not know. He has studied and made his pro of the studies of others. Yes that the man of our times knows more than the man of former times, and, as he goes up, much more and more. The first men knew nothing; they knew what you know, child.”). Magri, by studies, inclination and background, was an artist devoted to synthesis, and his background, combined with his ability to preserve the child’s gaze, led him to produce some works with an eminently childlike character, such as The Rope Game, a watercolor that imitates the naive figuration of a child who in his drawing does not intend to capture a moment but to describe it, or like The Apuan Alps from Barga, where the mountains are reduced to green and blue outlines to which the artist affixes the names of individual peaks. A motif, this, that returns in The Laundry, where the rhythmic scansion of the scene, with figures arranged paratactically in the foreground, is reminiscent of Romanesque reliefs and thirteenth-century panels.

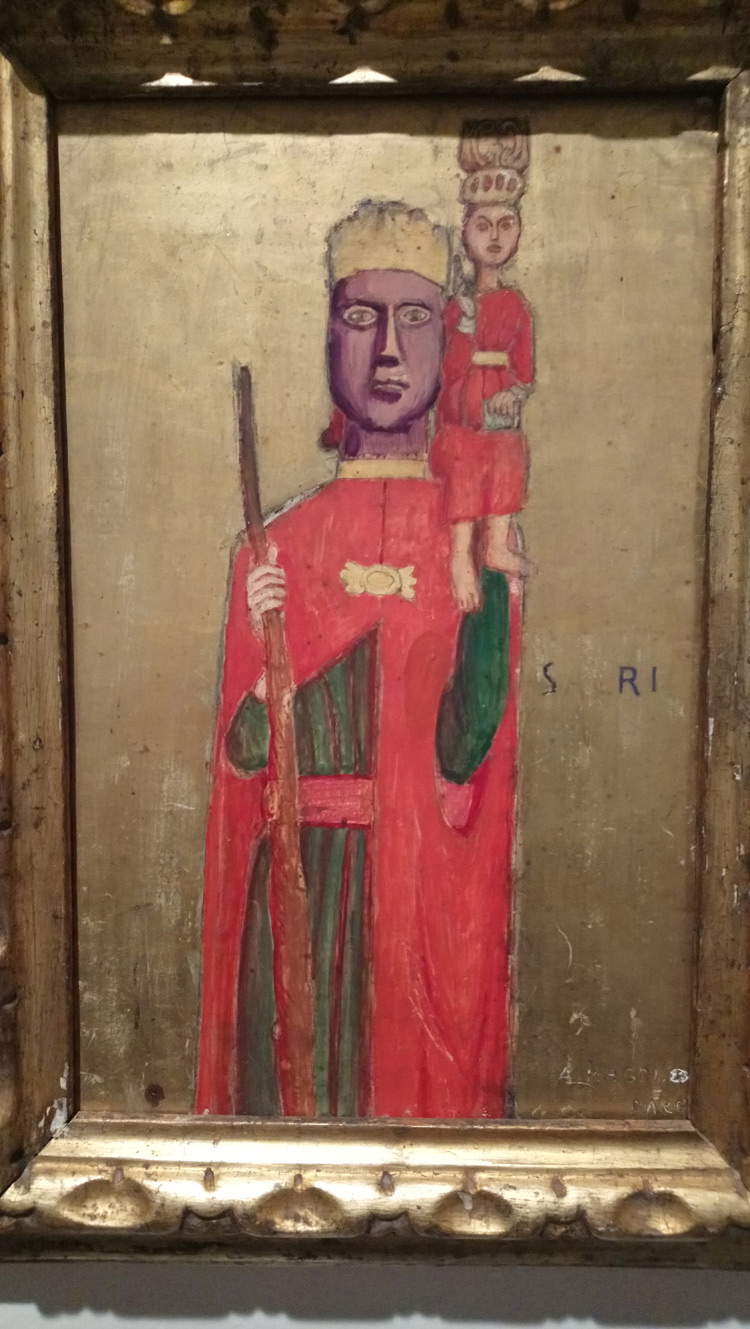

Already Ragghianti was convinced that Magri was an artist “who makes the Tuscan Dugento his exclusive and dominant poetics, the condition of his lyrical vision,” and one can point to him as the painter who best, among the Tuscan-Apuans, knew how to unite the infantilist base with the medievalist one. His polyptychs on field life(The above-mentionedLaundry, The Farmhouse and The Grape Harvest, all made between 1911 and 1913), for which Magri himself had declared his own figurative sources (“I have always frequented galleries, churches [.... admiring and studying preferably the painting and sculpture of the Giottesque and Pregiottesque periods”: proof of this are his reproductions of medieval works, such as the San Cristofano, exhibited in the exhibition, a tempera that reproduces the wooden statue of the thirteenth century preserved in the Cathedral of Barga). And so, looking at the Barga painted in the background of the third panel of The Farmhouse, one cannot help but think of the Arezzo that Giotto painted in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi, the sharp faces of the peasants moving across the landscape seem to come straight out of Berlinghiero Berlinghieri’s panels, and even the character on the right who, in The Grape Harvest, struggles to drag a chariot on his shoulders, seems an almost literal quotation from the month of October in the cycle of months in the Cathedral of Lucca, which moreover between 1922 and 1928 was translated into woodcut engravings by Lorenzo Viani (Viareggio, 1882 - Lido di Ostia, 1936). And Magri’s art at the time did not go unnoticed (Boccioni, for example, compared him to Henri Rousseau), and it also had its detractors, who saw in the evocation of ancient primitives a kind of mannerist intellectualism: but this recuperation of his, Raffaella Bonzano explained, was functional to “provide a spontaneous response to the need for conciseness of a Tuscan painter who had had as his only masters for his painting those admired in the galleries and churches of his native place,” and his recourse to childish schematisms was a means “to render concepts in as elementary and synthetic a form as possible.”

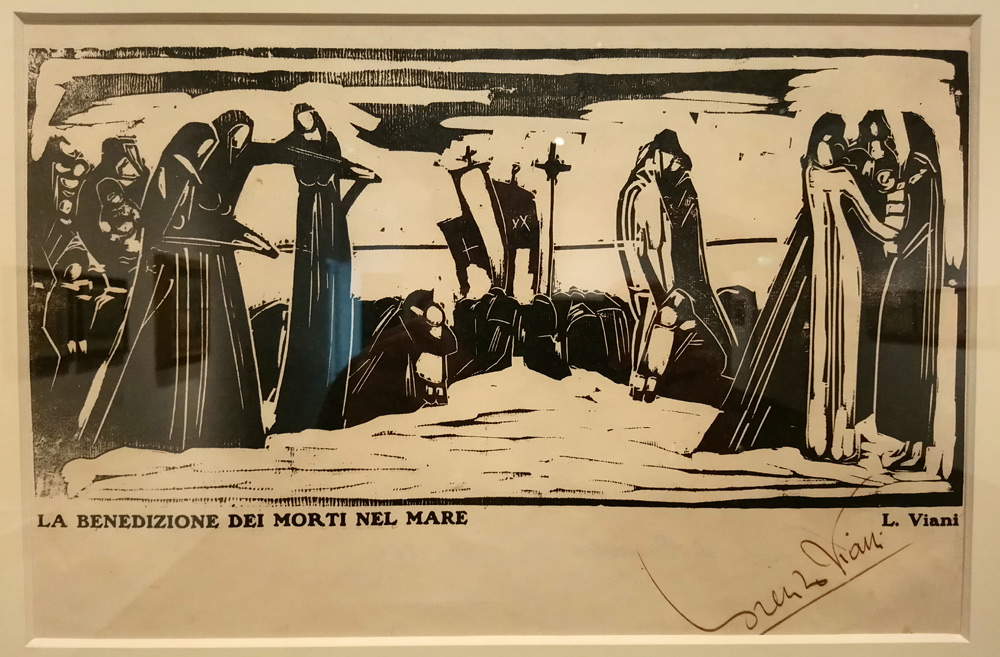

However, Alberto Magri also knew those who, to some extent, were fascinated by his research: it has been said of Viani, who of the group of Apuans (which group in the true sense of the term was in fact never) was probably the one best placed in art circles, and who, like Magri, shortly before the 1910s insistently took medieval art as a model (the layout of a work like The Blessing of the Dead of the Sea, present in the exhibition in its woodcut version, recalls that of the crowds of crucifixions in the reliefs of Tuscan pulpits). But the discourse could also be extended to Adolfo Balduini (Altopascio, 1881 Barga, 1957), who in several of his works (such as The Return from the Feast) reveals debts to Magri, of whom he was a friend: it was probably thanks to the artist from Barga that Balduini decided to start the enterprise of reproducing, he too with the medium of woodcut, the reliefs of the Barga Cathedral (some examples are present in the exhibition).

|

| Alberto Magri, The Rope Game (1906-1908; watercolor on paper, 13 x 21 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Alberto Magri, The Apuan Alps from Barga (1913; tempera on cardboard, 13.5 x 44.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Alberto Magri, The Grape Harvest (1912; triptych: tempera, pencil on board, 46 x 59 cm, 46 x 59 cm, 46 x 60 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Alberto Magri, The Laundry, Detail (1913; triptych: tempera, pencil on panel, 46 x 63, 46 x 90, 46 x 63 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Alberto Magri, San Cristofano (c. 1927; tempera on panel, 29.5 x 19 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Adolfo Balduini, The Return from the Feast (1920; tempera on chalk-prepared cardboard, 46 x 59 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Lorenzo Viani, The Blessing of the Dead of the Sea (1910-1915; woodcut, 180 x 170 mm; Siena, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena Collection) |

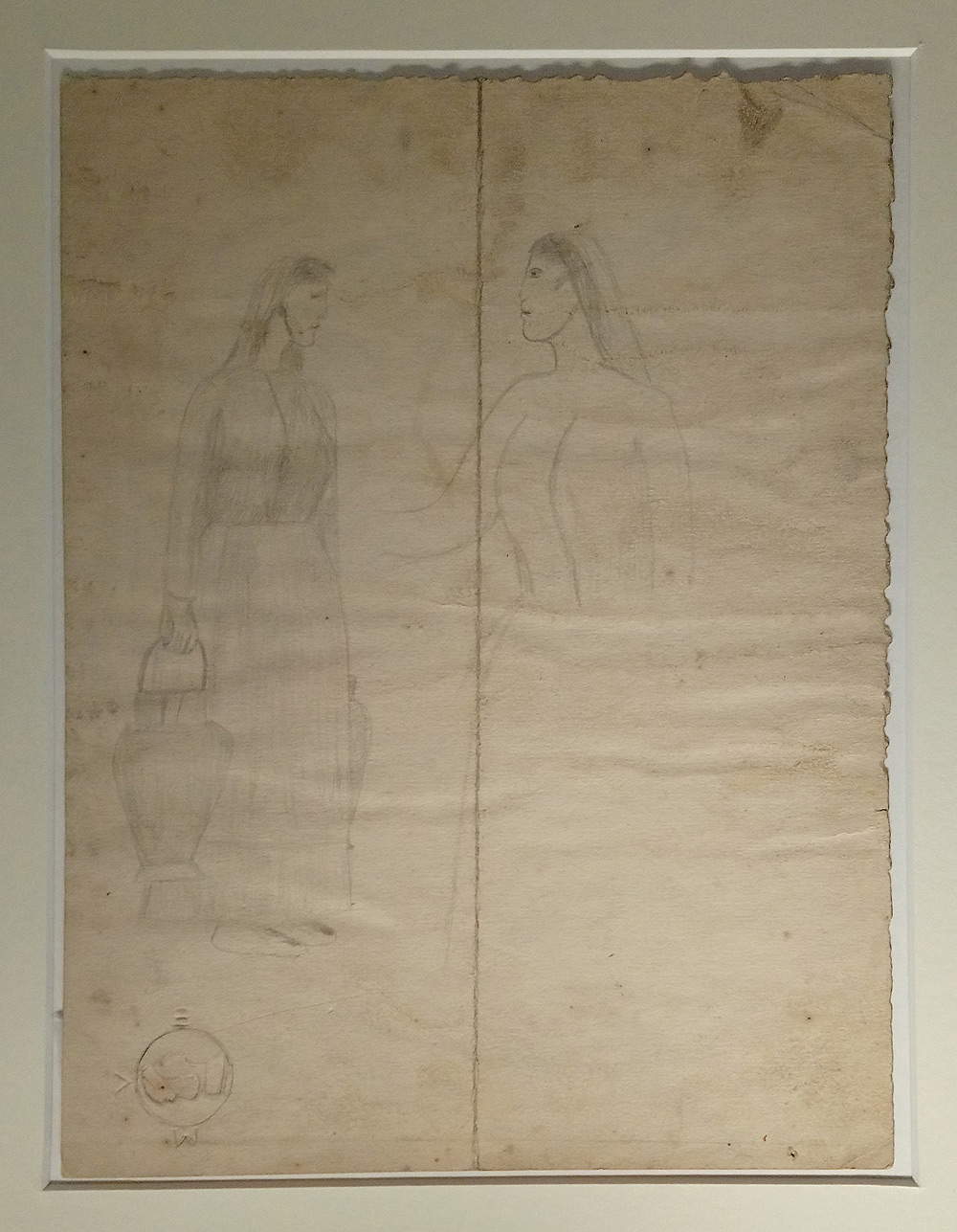

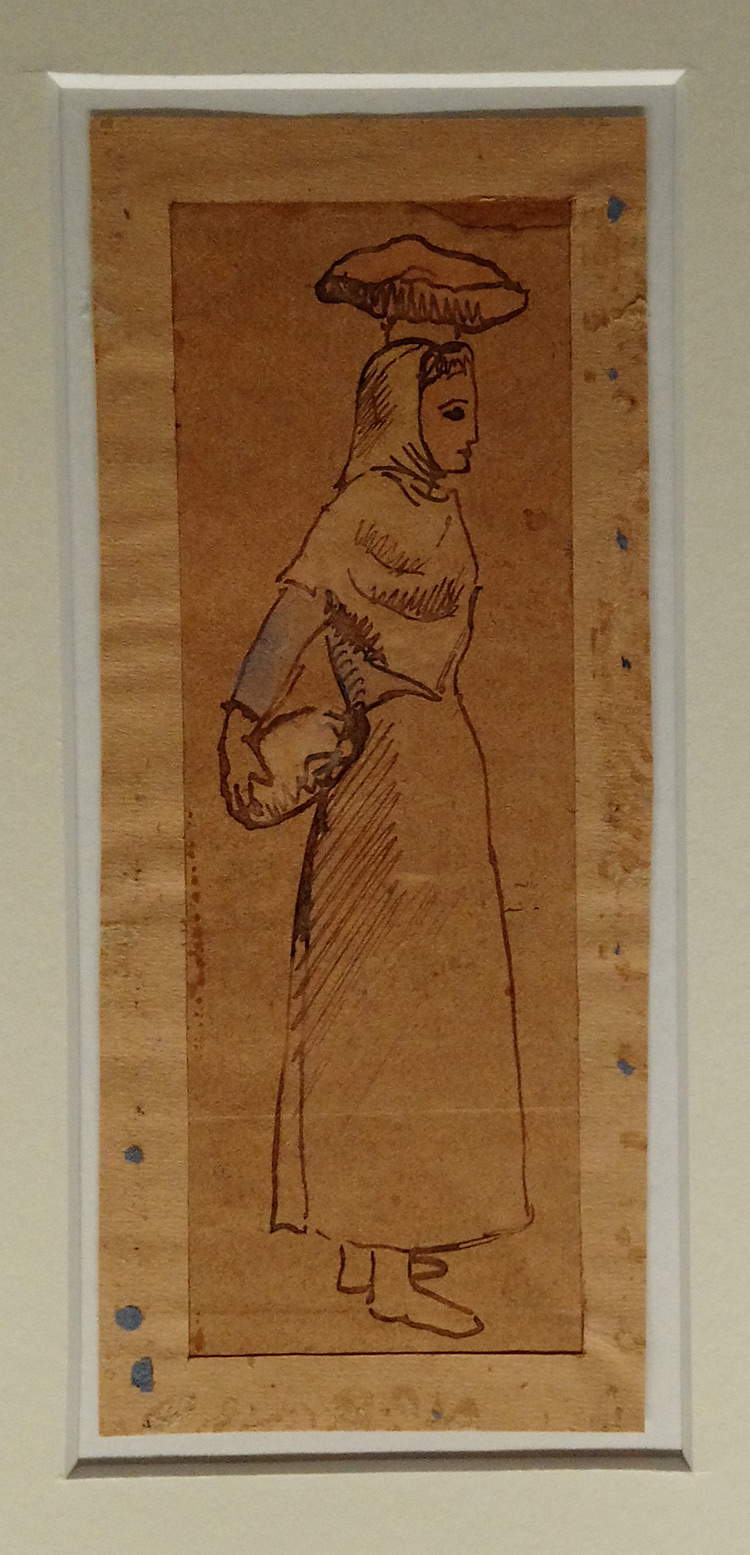

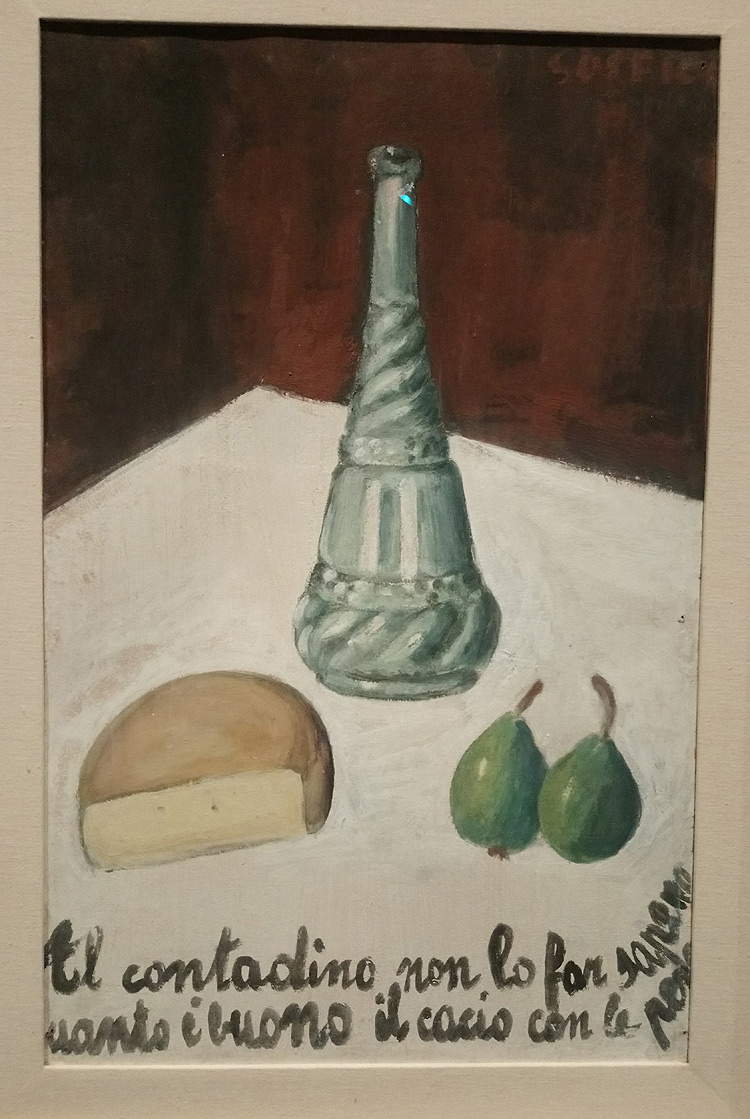

A quick mention has been made above of Henri Rousseau (Laval, 1844 - Paris, 1910): the presence in Lucca of a Dog’s Head by the famous “Dogman” allows us to open another front, which involves two capital figures for early 20th-century art, those of Ardengo Soffici (Rignano sull’Arno, 1879 - Vittoria Apuana, 1964) and Carlo Carrà (Quargnento, 1881 - Milan, 1966). Rousseau was in fact one of the most interesting discoveries of Soffici, who dedicated an article to the French painter published in the magazine La Voce in 1910 and became famous above all because it took the shape of a sort of manifesto (admittedly openly provocative, but equally certainly not insincere) of the convictions of the young artist and critic, a strong supporter of an art free from academic conventions (“the painting that I say,” wrote the voce-like Soffici in that famous article, is “more naive, more candid, more virginal, so to speak. It is the painting of simple men, of the poor in spirit, of those who have never seen a professor’s mustache. Painters, masons, boys, painters, half-crazed sheepherders, and vagabonds. Yeah!”). Rousseau’s was, in Soffici’s view, that he detested artists whom he considered dry and artificial (well known are his fierce critiques: and it is appropriate to reiterate how both Soffici’s discoveries and violent criticisms were the focus of a fine exhibition held at the Uffizi between 2016 and 2017), a free and genuine art, and the Florentine artist himself tried to grasp its essence, first by procuring works by the Doganiere, of whom he became a friend, and then also by taking to copying them. Soffici therefore became a habitué of local markets, looking for signs, canvases or tablets made by amateur painters: the exhibition introduces an interesting comparison between a sheet drawn by a shepherd, the "Fuffa," which with a few pencil marks on paper sketches the profiles of two peasant women showing those skills of synthesis that exalted Soffici, a Figure of a Woman by Pablo Picasso (Malaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973) that shows strikingly similar features to those of Fuffa’s countrywomen, and a large canvas by Soffici on loan from the Museo del Novecento in Milan, I mendicanti, where we note obvious points of contact between the modeling of the protagonist figures and those drawn by the sheep guardian.

These researches on formal simplification engaged Soffici for almost fifteen years (the exhibition ranges from the landscapes of the middle of the first decade of the twentieth century to the Cacio e pere of 1914) and were soon noticed by Carlo Carrà: indeed, Marchioni in his essay argues that the 1910 article on Rousseau was decisive in Carrà’s departure from Futurism. On June 1, 1914 (curiously enough on the eve of an Alberto Magri exhibition held in Florence), the artist of Piedmontese origin published an article in Lacerba that on the one hand lashed out against the “false primitivisms” of foreign expressionists (Carrà did not appreciate the desire to draw on non-European cultures), and on the other reaffirmed “the imagination that we Futurists have always shown for popular art forms,” and the conviction “that only in the cues of the direct, anti-academic, anti-drogue, anti-mbecile art of the anonymous plebeians can we find the scattered shreds of pale Italian genius.” These are the premises of Carrà’s abandonment of Futurist instances, who then, in the full climate of rappel à l’ordre and in the wake of Soffici’s reflections, would come to the conclusion that the only possible primitivism for Italy is that which refers to the “plebeian virginity of Giotto and the other primitives , fought and defeated by later intellectualisms” (so wrote the artist in a further article published in La Voce on March 31, 1916), and that a sincere art needed an approach to reality similar to that of a child (making manifest such intentions, in the exhibition, is a Horse drawn by Carrà in 1915).

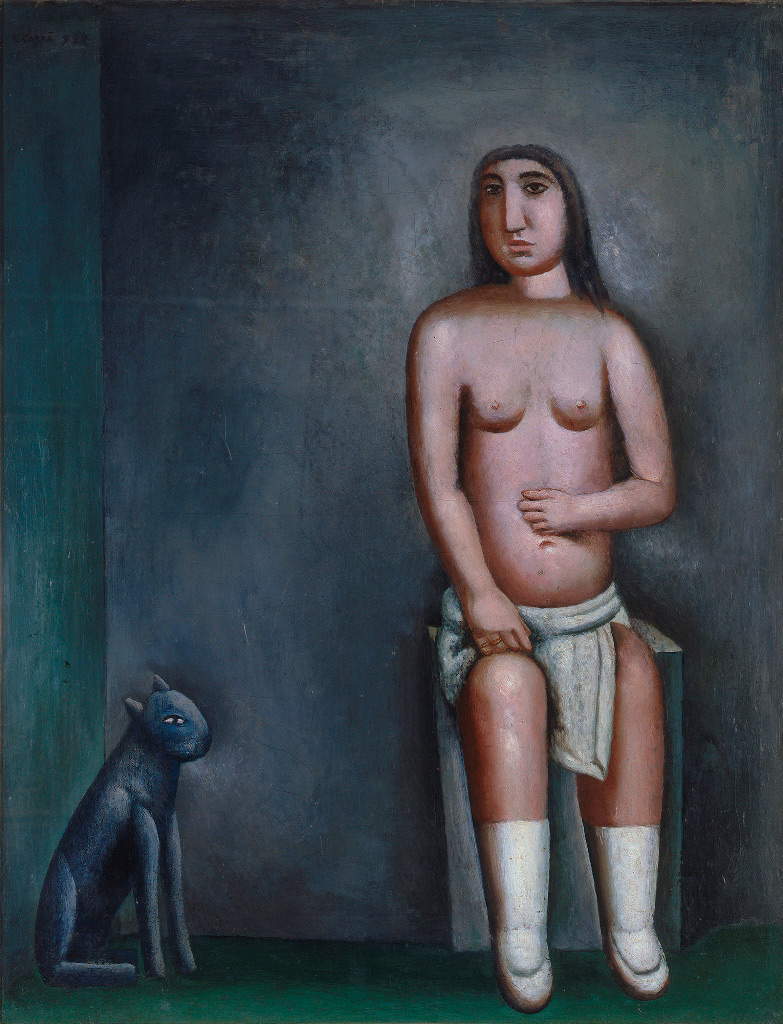

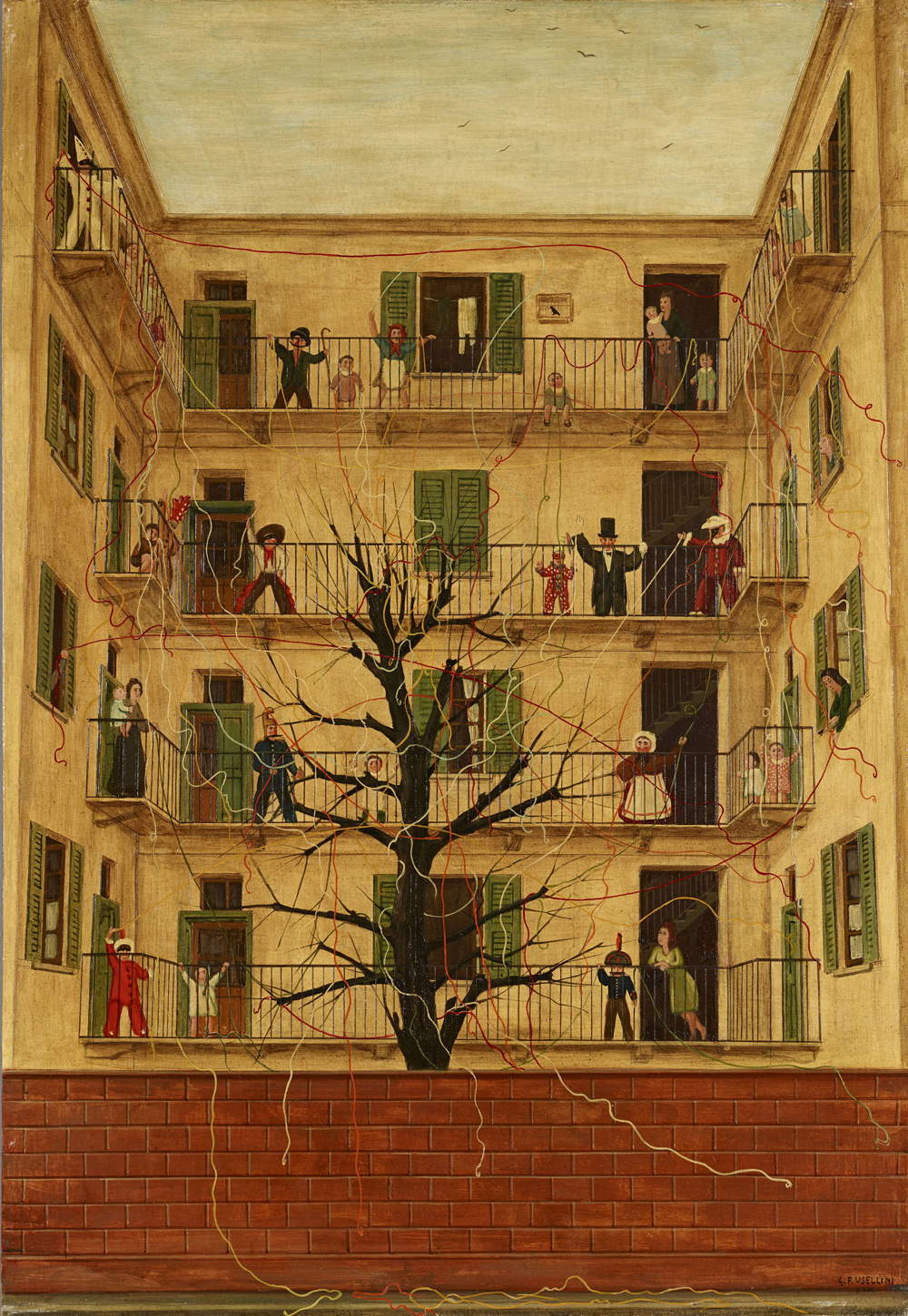

After a brief section, the fifth, devoted to the spread of child primitivism in propaganda images during the period of World War I, a spread due as much to questions of form (a communication similar to that directed at children was considered highly effective: the public got to observe the immediacy of illustrations by artists such as Soffici, Carrà, De Chirico, and Sironi) as much as for reasons of content (the child waiting at home for the return of his father engaged on the front was a rather beaten topos: an example of this is Duilio Cambellotti’s Il ritorno ), we come to the epilogue, a brief overview of the persistence of infantilism in the art of the 1920s and 1930s. The results of Carlo Carrà’s work, despite the fact that in 1921 the artist had established that the days of “child art” were over, are appreciated in La casa dell’amore of 1922, and a certain form of opposition to the changed art scene (to dominate in the years following World War I would be the metaphysical artists and the classicism of the Novecento group) is recognized in the works of artists such as Fillide Levasti (Florence, 1883 - 1966), present with La fiera from about 1920, or like Riccardo Francalancia (Assisi, 1886 - Rome, 1965), whose Ritratto di Gustavo (the artist’s son) from 1923 is exhibited, showing glimmers of openness toward metaphysics. It concludes with the conscious revival of infantilist instances in the 1930s: the exhibition closes by showing the public Gianfilippo Usellini ’s Il carnevale dei poveri (Milan, 1903 - Arona, 1971), where the joyful accents typical of children’s painting make a poor Milanese suburb cheerful in its carnival celebrations, and hinting that the interest in childhood would continue to remain alive for much of the continuation of the twentieth century.

|

| “The Fuffa,” Two Peasant Women (1899; pencil on paper, 25 x 19 cm; Milan, Soffici Heirs Collection) |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Figure of a Woman (1906; ink and watercolor on paper, 15.7 x 60 cm; Milan, Soffici heirs collection) |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, I mendicanti (1911; oil on canvas, 120 x 145 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento) |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, Cacio e pere (1914; tempera on cardboard, 70 x 45 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Carlo Carrà, The House of Love (1922; oil on canvas, 90 x 70 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Riccardo Francalancia, Portrait of Gustavo (1923; oil on canvas, 60 x 56 cm; Rome, Museo della Scuola Romana di Villa Torlonia) |

|

| Gianfilippo Usellini, The Carnival of the Poor (1941; tempera on panel, 130 x 90 cm; Rovereto, MART - Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto) |

The exhibition L’artista bambino intervenes with a high-level scientific project in the context of an art-historical debate that is still open and arouses growing interest, providing the public with useful and broad keys to approach a complex and fascinating theme. But there are also other important results achieved by the exhibition: having placed in a renewed light the art of the Tuscan-Apuans, whose vicissitudes critics have been dealing with for some years but who are still almost unknown to the general public (and the section on Alberto Magri and countrymen, besides being the largest and most complete, is also the most original), and again the work on Cecioni’s works and writings, the ability to have given rise to interesting comparisons (such as the one between Magri and Balduini, or the one involving Fuffa, Picasso and Soffici). If the exhibition loses a little consistency as we approach the final bars, we can nevertheless benefit from the fact that the presence of children’s magazines often returns punctually in the exhibition, a sort of common thread that binds almost all the sections of the exhibition and to which the director of the Ragghianti Foundation, Paolo Bolpagni, devotes an in-depth discussion in the catalog (and perhaps the cross-references between art and publishing are one of the most compelling themes of the exhibition, although no mention of them is made here). All in all, a contribution in many respects important on the theme of primitivisms in early twentieth-century art in Italy, and an exhibition that, while strongly rooted in its own territory, addresses a topic that extends well beyond regional borders and, indeed, invests themes that animated the European debate in the period under consideration and that in Italy were addressed with a certain originality.

The catalog is probably the weakest point of the review: certainly not because of the quality of the essays, but rather because of how it was structured. That is, there is a lack of worksheets (although, for exhibitions dealing with nineteenth- and twentieth-century art, this is now becoming more of a rule than an exception) and a structured bibliography is also lacking, which is why it is necessary to scroll through the notes of individual contributions several times to find a source or reference. But on the whole, it can be said that L’artista bambino represents a quality exhibition, one that responds well to that need, recalled by Ragghianti in his crucial Bologna 1914 essay published in 1969 and rarely analyzed with any depth, to delve into aspects of primitivism in early twentieth-century Italy because of what the scholar called “the problem of child art between the 1900s and the 920s.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.