“Unclassifiable.” This is the adjective, simple but extremely eloquent and fitting, that a few years ago Eskil Lam found to describe the art of his father, Wifredo Lam. There is perhaps no definition that better fits this artist so out of the ordinary, so versatile, so extraordinarily contradictory. Those who visit the fine exhibition that Savona and Albissola Marina are dedicating to him this summer(Lam et les Magiciens de la mer), commendably curated by Luca Bochicchio, Stella Cattaneo and Daniele Panucci, will find in the first of the two venues, the Museum of Ceramics in Savona, a poster bearing a phrase by Wifredo Lam: “my art is an act of decolonization.” These words are excerpted from an interview Lam gave in 1980 to the well-known Cuban critic Gerardo Mosquera, the historic curator of several editions of the Havana Biennial (he was a young man of thirty-five at the time), and the artist was talking about his most famous, La Jungla, painted in Cuba in 1943 and now housed at MoMA in New York (incidentally, interestingly, the Museum of Ceramics in Savona has a ceramic relief, on display in the exhibition, where a mask can be seen that is almost identical to the one in La Jungla on the left, with its double crescent-shaped face, pointed ears, long hair, small round eyes, and protruding lips). Lam said that in Jungle (but the argument could be extended to many of his other works) he had tried to “relocate black cultural objects in their own landscape and in relation to their own world.” And this was some forty years before discussions on decolonization became almost a daily occurrence in the cultural debate, before relocations and restitutions became a goal to be pursued, and above all before African or Afro-descendant artists became the object of the attentions of a contemporary art market that, sensing the trend, immediately pounced on the theme of decolonization, operating a sort of return colonization that at the moment seems to have reached its peak at last year’s Venice Biennale.

It may seem natural, therefore, to attach to Wifredo Lam all those stereotypes that naturally accompany such an energetic, stentorian and epigraphic statement as the one rendered in Mosquera. For example: here is the Cuban artist, genuine and uncorrupted by the West, who by the sheer force of his exoticism, his origins, his panic and earthy mysticism, his black pride imposes his art in white Europe redeeming his people from centuries of colonial abuse. Actually, to derive such an image from Lam’s art and words is a bestiality equal, for example, to that of New Yorkers in the 1940s who, intrigued by his Antilles background, thought him a sort of witch doctor and were surprised by the fact that he ordered an aperitif at the bar exactly as they did: it is Lam himself who recounted this anecdote in an interview with Oggi in the early 1970s. The situation is decidedly more complex: the son of an octogenarian Chinese immigrant and a local woman (father and mother were separated by an age difference of forty years), Wifredo Lam, given the widespread racism that raged in Cuba at the time and that he had to endure because of his mixed origins, was much better off in Paris with Picasso, with Lévy-Strauss and with Lévy-Bruhl, or in New York amidst abstract expressionists, than at home. And when it fell to him to return to Cuba in ’41 because the Nazis had invaded France, he, if he had the choice, would have gladly stayed in Paris. He did not like the fact that Western museums collected African art, often the result of raids and looting, but he in turn was a strong collector of the very works he would not have wanted to see in museums (although it should be emphasized that this form of collecting was for Lam a way of claiming his origins and thus the heritage of his ancestors). His works are strongly inspired by santería and Afro-Cuban and Afro-Caribbean cults, but he was an atheist. The urge to rediscover his origins had come to him not from an innate awareness, but by frequenting the cosmopolitan Paris of the early twentieth century: until he was thirty-six years old, that is, until before he went to Paris, Wifredo Lam had been a portrait painter. He believed that he had with him, in his own words, “the magic of the forest and the directness of primitive men,” but in Albissola Marina he lived in a beautiful villa with a swimming pool, amidst the comforts: he may be accused of inconsistency (although consistency, as is well known, is the stuff of fascists), but certainly not of hypocrisy. Because success, critically and commercially, was for Wifredo Lam a source of redemption.

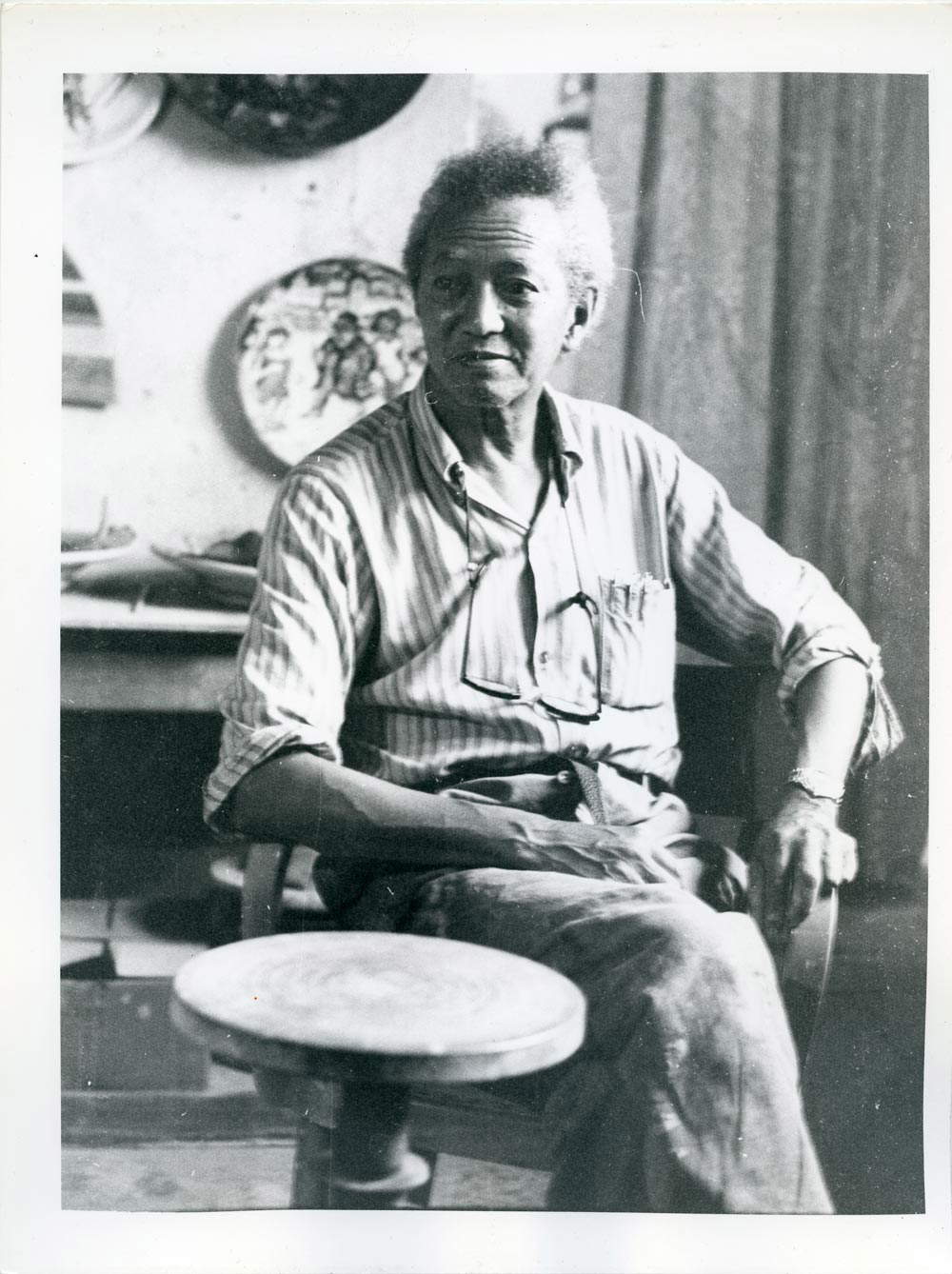

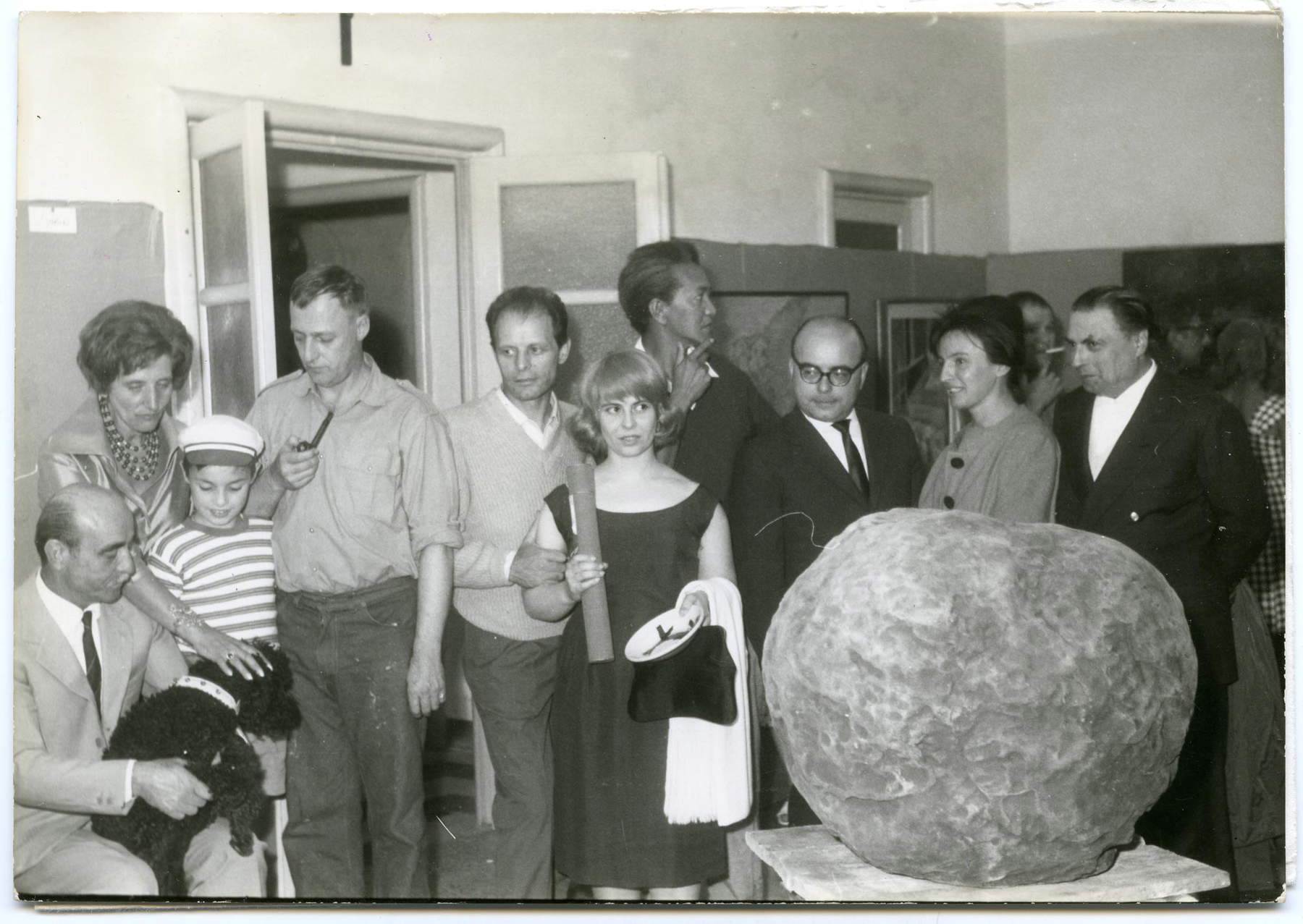

The strength and greatness of Wifredo Lam’s art lies not in the clichés that might too easily be associated with it, but in its extraordinary and delicate balance and the novelty of its underlying purpose: namely, as Claude Cernuschi has well noted, that of turning Western primitivism against itself. “Lam deliberately appropriates, but reformulates, European modernism to serve anti-European ends,” the scholar has written. “The point, in particular, was to return the same African masks sold as trinkets in European capitals to their ’appropriate’ environment: in his case, the Afro-Cuban religious milieu to which he had been exposed as a child and to which his Cuban associates, intellectuals and anthropologists such as Fernando Ortiz, Lydia Cabrera and Alejo Carpentier, paid serious attention. If successful, the return of African artifacts to their proper context would reverse the over-commercialization of black culture in Europe and, at the same time, enhance the very African religions that had long been vilified in Cuba’s racist climate.” Lam’s arrival in Albissola Marina, where he first stayed in 1954 before returning several times and settling here since 1962, added another layer of meaning to his art. In Albissola, Lam discovered pottery, an activity he had never practiced (except in Cuba, for a short time, in order to learn its rudiments), but not only that: he discovered a unique microcosm, a universe where some of the greatest artists of the time worked side by side, followed by the artisans of tærra bÅnn-a, as clay was called in these parts. Most importantly, by getting close to the earth, that is, the humblest traditional element an artist could handle, and to those who worked it, Wifredo Lam got to feel “a real sense of belonging,” as Eskil testifies.

Layouts of

Layouts of Layouts of the

Layouts of the Layouts of the

Layouts of the

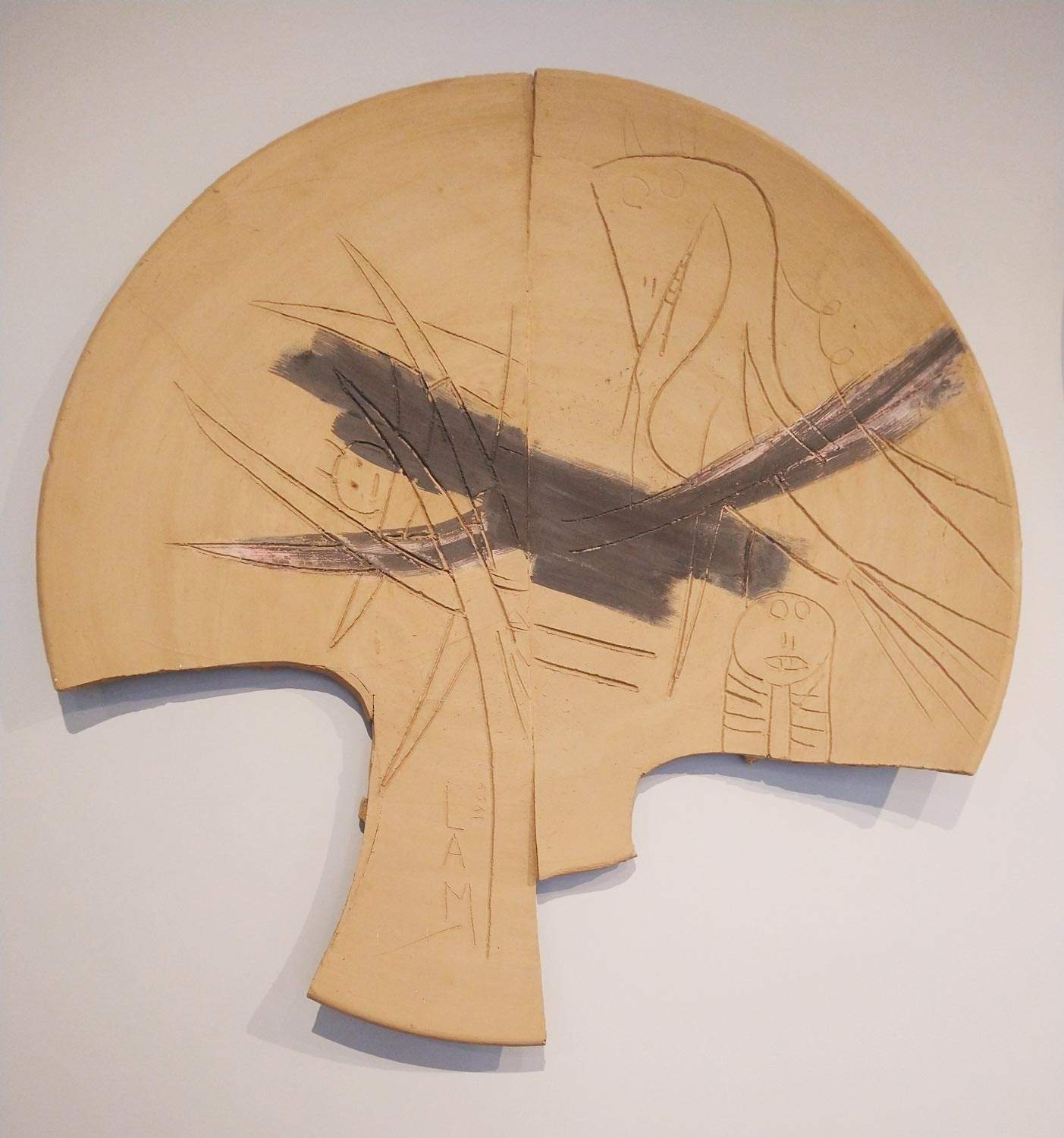

Visitors to the exhibition are given the option to begin their journey indifferently from Savona or Albissola Marina. It is, however, from the ceramics village that one can start with a good overview, because at the MuDA Exhibition Center in Albissola Marina the public is not only duly introduced, as in the Savona venue, to the history of the relationship between Lam and ceramics, but also has the opportunity to get a concise idea of the Cuban artist’s entire ceramic production, to be then deepened in the thematic sections of the Museum of Ceramics in Savona. However, the curators have had the good sense not to create a simple summary in Albissola, because this chapter of the exhibition also includes works that are fundamental to understanding the way Lam’s language changed over the years, as well as a selection of works by other artists close to Lam, who worked during the same period in Albissola, and who sometimes imitated him. One of the most dense moments of the exhibition is the comparison of a fragmentary terracotta by Lam from 1959, a slightly later ceramic, from 1962, by Roberto Crippa, and an additional plate, from 1972, by Asger Jorn. Lam’s plate, one of his very first experiments with terracotta, is surprising for the simplicity, immediacy, and instinctiveness with which the artist etches the clay, using a stick or a stick, to trace the silhouettes of the figures typical of his repertoire (real or fantasy animals, strange idols, primordial totems): the essentiality of Lam’s sign will have a certain fascination for Roberto Crippa, who had begun his own research on totemism before Lam arrived in Albissola, and still managed to catch the strali of Piero Manzoni, who, in fact, accused him of being insincere. In an article published in Pensiero Nazionale just in 1959, Manzoni, who had met Lam in Albissola, praised his “characters that originate from the wild totems of his land and from the Cubist lesson” (the young colleague had thus grasped the two different souls of his art, the Afro-Cuban and the Western), adding that “it is only since a few years that here in Italy some mediocre artists have begun to imitate him; but the local copies make a very poor figure in front of the high level and true value of the originals.” In the article, Manzoni did not mention Crippa’s name, which does, however, appear in a letter sent two years earlier to Enrico Baj (“I think that it is now time to make a clear attack on the posthumous totemisms of Crippa and Peverelli”). Yet, as Luca Bochicchio explains well in the catalog, Lam’s totems and those of Crippa and the other Europeans who were providing their own interpretation of non-European arts (in a nearby showcase is exhibited, for example, a totemic Flower by Mario Rossello) are incomparable because they are the result of independent research, moreover chronologically distant. Manzoni, moreover, in his article also had some for Jorn, whose work was hastily branded as a “banal romantic expressionist regurgitation.”

It seems superfluous to point out the excess of severity in Manzoni’s lapidary judgment, since much has been written about Jorn in these pages: however, it is interesting to observe his work side by side with Lam’s in order to understand how the two artists managed to converse in a fruitful way (in this case even on a formal level, with Jorn etching red earth and working with black engobe to achieve that bichromatic effect typical of many of Lam’s ceramics), moreover forging a sincere and lasting friendship, traced in detail by Daniele Panucci in the catalog: the two artists, the scholar writes, were “capable of activating themselves like ethnoanthropologists and setting out on the trail of their own origins and the popular and mythological artistic expressions of their respective home cultures”: the fact that Jorn was Danish did not make him any less attentive than Lam to his own roots.

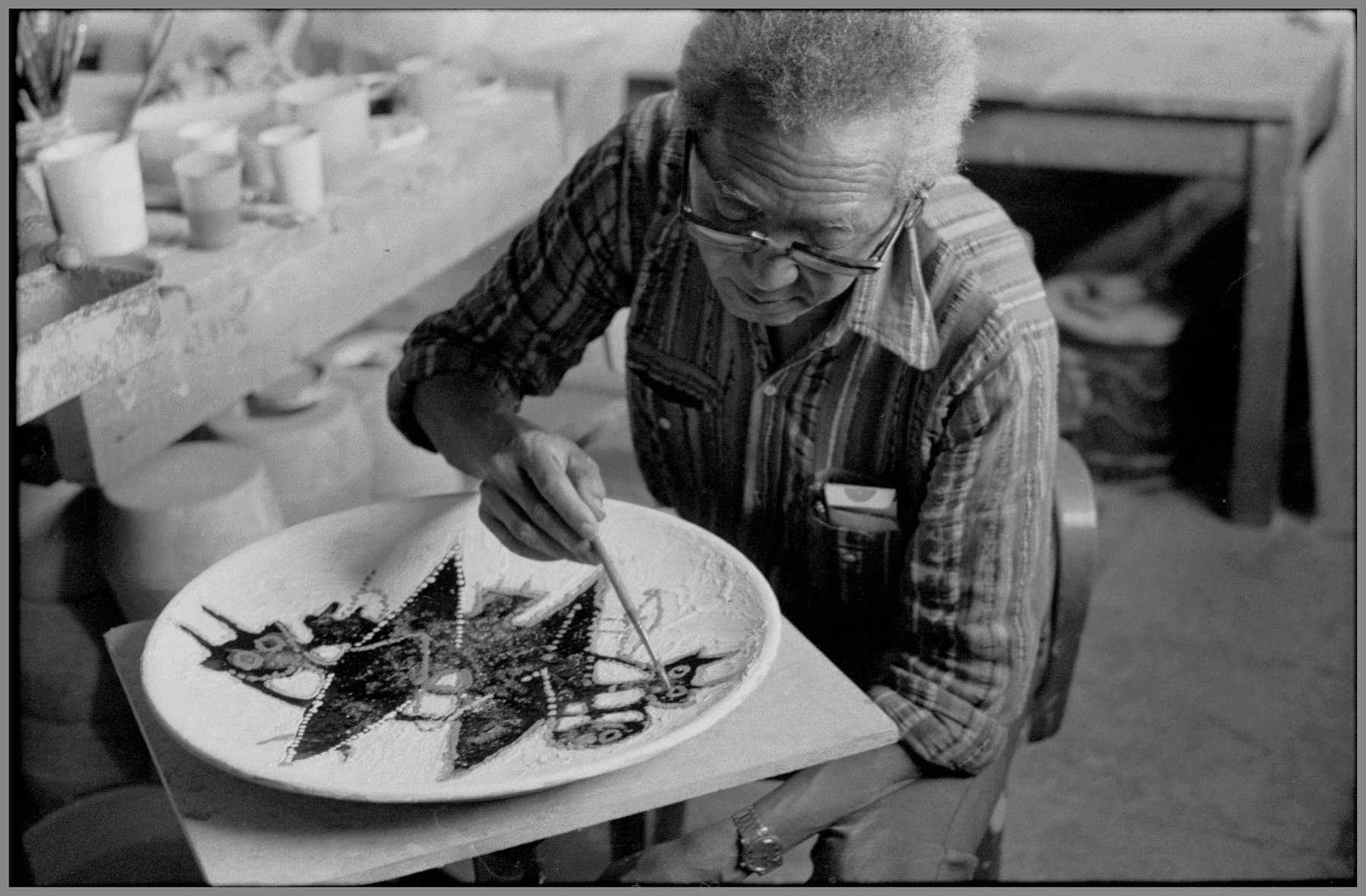

Also at Albissola Marina’s MuDA, an entire wall offers an intense overview of Lam’s experimentalism in Albissola Marina: the artist, who worked at Ceramiche San Giorgio, founded in 1958 by Eliseo Salino, Giovanni Poggi and Mario Pastorino (specifically, it was Giovanni Poggi who was Lam’s tutelary deity, the “torniante,” as on this strip of the Ligurian coast the specialists of the potter’s wheel are called on this strip of the Ligurian coast, who assisted the Cuban artist, far from mastering the secrets of the trade, in the realization of his works), had occasion to reason at length about his modes of expression. At first, his ceramics were nothing more than extensions of his painting activity: Lam did nothing more than paint on terracotta plates what he previously painted on canvas. Then, his experiments began to acquire a continuous and steady autonomy from painting: these continuous changes of register can be appreciated in the plates that the curators have lined up in the exhibition, with the glazes often acquiring a relief and solidity that give an almost sculptural aspect to certain works, while in others the spreading of color follows a spontaneity reminiscent of that of his friend Jorn, until reaching the extreme peaks of the work De la terre in which Lam arrives at pure abstractionism, working even with fragments of various materials such as glass, sand, and earth. It was as if in Albissola Marina the artist had rediscovered his origins. Or at least, he had found there an environment entirely congenial to his research: a land of simple, humble people, attached to their traditions, but also open to the new. And he happened there at a time when the city had become a kind of great international cenacle, capable of attracting the most up-to-date artists in Europe. Here, then, are the Magiciens de la Mer that give the exhibition its title: not a vacuous reference to the more famous Magiciens de la Terre from the 1989 exhibition at the Centre Pompidou. And, more importantly, between the curators who chose the title and the magiciens there is not that detachment from the Centre Pompidou exhibition that seemed problematic at the time and that had provided pretexts for even fierce criticism (curator Jean Hubert Martin was accused of having carved a furrow between Western art and that of the magiciens, seen somewhat as artist-shamans according to outdated clichés ). Here the risk is not taken, if only because the curators of the exhibition were born and raised in the world of the “magicians of the sea”: by this expression they mean to refer to all those who made that unrepeatable, magical moment possible: the master potters, formerly known as “arcanists,” Stella Cattaneo explains, since they were “holders of the mysterious recipes for the creation of clay mixtures, colors, glazes and firings,” and the artists whom Lam had found upon his arrival and who would continue to frequent Albissola for at least a good two decades. Like true magicians, they knew how to create an alchemy capable of giving rise to one of the most fertile and important seasons in the history of twentieth-century art.

And among the goals of the exhibition is to provide the correct placement of Wifredo Lam within this context. In Albissola, writes Luca Bochicchio, “this curious convergence between research derived from different European avant-garde movements and currents was vneuta to be created, which found in the reactive and dynamic matter of clay the most suitable medium to give substance to irrational and primitive (in the sense of primordial) visions.” Savona’s figurative culture (in ancient times pottery was produced in Savona) was filled with hybrid, imaginative, mythological figures, or those linked to popular beliefs. While between the 1940s and 1950s, the researches of artists who worked in western Liguria abounded with “ambiguous and metamorphic, bifacial and hybrid beings,” “totemic, robotic and natural compositions.” Lam’s researches drew energy from this context, and in turn provided suggestions to the artists who worked here, as the exhibition aims to demonstrate. At the center, are his totem poles (also in the Savona section one can admire some plates on which one can observe the extravagant idols that were seen in Albissola): for Lam they are a symbol of cultural reappropriation, and the complexity of his figurations, much more elaborate than the totems of a Crippa or a Rossello, reflects the elements underlying his work, which is sustained, Bochicchio again writes, “not only by an inner research, but by a methodical work on structural and social awareness, within which santería assumes the value of a cultural, symbolic and political, as well as spiritual and religious, system.” Lam’s totem poles mix human, animal and plant elements in accordance with the principles of santería whereby devotees seek to touch the soul of all things, believing that the universe is dominated by “aché,” the spiritual energy that can be seized by the faithful to be guided in the world. Cernuschi noted, however, that the choice of the title “totem” for his works is culturally oriented, but not in the sense we would believe: using a term that was indeed derived from a Native American language, but which is nonetheless an Anglicization and especially is used in anthropology, Lam was revealing a considerable epistemological distance “from the very culture he was seemingly naturally trying to evoke with his art, revealing himself to be no different from his European and American colleagues,” the scholar wrote, pointing out also, however, that Lam may have reasoned about this choice, using a familiar term, and especially that the hybrid and metamorphic forms of his works were in themselves sufficient to denote the origins of his culture without distorting their bearing.

The varied and exuberant hybridity of Lam’s totems seems indeed unknown to his colleagues: this is the clearest indication of the naturalness with which the Cuban artist constructed his own totems. In a pair of plates exhibited in Albissola, for example, one sees two women with two birds on their heads: in Afro-Cuban culture this is a symbol of knowledge. In Savona, on the other hand, one admires a pair of depictions of the woman-horse, a recurring figure in Afro-Cuban rituals, a symbol of the divinity that takes possession of a person’s body to infuse it with its aura of sanctity (it should be remembered that santería blends elements of Catholic belief with elements of the animist religions of the African slaves deported to the Americas): the horse, in particular, is an allegory of theorisha (the saint) who ’rides’, as it were, the spirit of the devotee. Among the animals Lam most often depicts in his works are birds, which play a prominent role in santería rituals, since they are commonly immolated as offerings to the deities (devotees believe that orisha drink the blood of sacrificed animals to strengthen their aché). At the Museum of Ceramics in Savona, a section is devoted precisely to animals: Significant is the comparison with a 1963 plate by Roberto Crippa, also depicting a bird, which reveals clear points of contact with Lam’s works, although the artist displays a cleanliness and minimalism that are unknown to Lam, and with two other extraordinary mirrored ceramics also by Crippa, one, very peculiar, depicting his dog Fungo taking on the forms of a very elaborate tureen that seems almost to be made of copper, and the other translating instead into almost geometric forms the figure of a centipede.

The works on display also capture and fascinate by their stylistic features and formal references: two sections are devoted to metamorphosis and sign. Metamorphosis is to be understood as much on the symbolic level (the hybrid forms mentioned above) as on the material level: thus, extremely experimental works are exhibited through which Lam and the artists who worked in Albissola transform matter by giving it a different appearance than one would expect (as in Eva Sørensen’s strongly textured plates, where multiple layers of earth and color thicken), or again by combining clay and earth with different materials, or by achieving quite particular and unusual tactile or visual effects: see, for example, Enrico Baj’s Mountain Head, or Rinaldo Rossello’s curious and little-known Spatial Little Men with their unusual reflections and with the texture of the material changing dramatically on the front and back, or Ansgar Elde’s panel that combines engobes and glazes to give a strong impression of movement to his colorful creatures that wiggle and transform on the surface of the clay. The section on sign, on the other hand, hints at the research, which began in the 1950s, on all the possibilities that sign, imprinted on a surface or left free in space, offered artists: the visitor will find a marvelous vase by Lam, owned by the Museum of Ceramics in Savona, in which figures typical of his imagination are etched on a vase in the colors of the sunset and with the surface giving the appearance of a sandy texture, evoking images of Caribbean beaches. Then there is a plate by Giuseppe Capogrossi where the typical trident signs on which the Roman artist used to base his figuration are combined, until we come to two Spatial Concepts by Lucio Fontana (the holes, in particular) that dialogue with a plate by Maria Papa Rostkowska whose surface is engraved with vertical signs reminiscent of Fontana’s cuts, and with the aforementioned plate by Eva Sørensen that cannot fail to recall the Natures of Fontana himself.

Lam et les Magiciens de la mer is the test of maturity, fully passed, for the very young Museum of Ceramics in Savona, born only in 2014 and run by a team of enthusiastic 30-year-olds who were able to organize an excellent research exhibition (several, moreover, unpublished works on display), which is, however, able to lend itself to multiple levels of reading, thus proving suitable for a wide audience. Arrangements that put the visitor in a position to walk through the exhibition freely but without ever losing the thread. Concise apparatuses but capable of offering a complete information framework (there are also in-depth insights made available through QR codes), with even a path for children. A rich calendar of collateral initiatives (a guided tour with the curators is highly recommended). An enthralling visit itinerary, devoid of smears, and able to offer many insights: from the personal history of Lam’s arrival in Albissola, retraced also with an accurate documentary section that the public will find on the second floor of the Museum of Ceramics, to the focus on the artists who frequented Lam’s own workshops at that time, from the insights on more purely formal issues to the delicate yet profound way in which the exhibition manages to talk about decolonization. Indeed, it could be said that the Savona and Albissola Marina exhibition demonstrates that it is possible to address the issue in a natural, serious way, and without the slightest rhetoric. Finally, a well-structured catalog, in three languages (Italian, English, and Spanish), with a striking editorial layout, texts by the curators and by Eskil Lam, Dorota Dolga-Ritter, Flaminio Gualdoni, Claude Cernuschi, Bruno Barba, and Surisday Reyes Martínez: a good compendium of the exhibition and a complete and up-to-date publication on Lam’s ceramics, to be seen also as an excellent starting point to delve into the rest of the artist’s production as well.

The public will find between Savona and Albissola Marina an exciting narrative and a new exhibition: it is the first retrospective dedicated to the relationship between Wifredo Lam and ceramics, a new topic of investigation for art research of the time. The exhibition therefore draws additional importance from the fact that it begins to fill a void. Moreover, insiders will be able to measure themselves against a fresh, dense and innovative exhibition, capable of demonstrating that it is possible to work on art history in new and transversal ways, and that research can be done without losing sight of the public. It could not have been otherwise for an exhibition set up according to those same criteria of openness and sharing that fostered the birth of that legendary community of artists and ceramic masters that even today many, between Savona and Albissola Marina, remember with light in their eyes. The wizards of the sea, indeed. That same community that welcomed Lam as if it had always known him.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.