It can happen that an ancient civilization is rediscovered centuries later and suddenly gains great popularity. This is what happened to the Etruscans over time. In the 16th century, large tombs emerged in Tuscany containing exceptional objects and inscriptions in a language unlike any other, Etruscan. After the finds, the civilization was appreciated and sometimes reinterpreted as a new cultural fashion. We know that at the height of their power, the Etruscans dominated a territory stretching from Campania to the Po Valley, with cities such as Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Vulci, and Populonia thriving on mineral wealth. Trade contacts with other cultures (with the Greeks in particular) thus enabled the creation of sculptures, paintings, ceramics and metal objects of great quality. In truth, beginning in the 4th century BC, Roman expansion gradually reduced Etruria’s independence, incorporating it completely into the empire by the 1st century BC. In the 19th century, the rediscovery of ancient Etruria thus restored a fascination for the Etruscans that won over scholars (and the public).

Currently, Etruscan artifacts are scattered in several international museums. But for what is the reason? Aren’t they all in Italy? No, Etruscan artifacts are not found only in Italy, as is the case with Roman, Greek or Egyptian ones. First, the international antiquities market has encouraged the dispersal of archaeological objects. Often private dealers sold them to foreign collectors, allowing foreign museums to acquire them (somewhat as in the case of the artifacts held at the Getty Museum). Second, many artifacts arrived abroad through donations or bequests from Italian collectors who were transferring their collections. In general, the dispersal of Etruscan artifacts reflects a historical context in which the protection of cultural heritage was regulated differently and material culture was perceived more as a symbol of international prestige than as local heritage to be guarded and preserved.

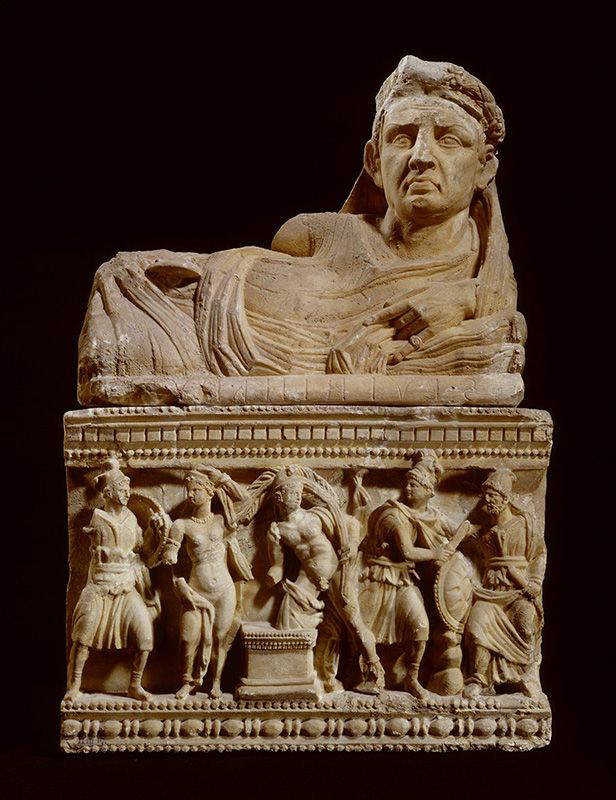

Let us start with the British collections. The rich selection of Etruscan objects on display within the British Museum in London illustrates daily life and beliefs in pre-Roman Italy. Known in ancient times for their deep religiosity, skill in metalworking, and love of music and banquets, the Etruscans left a vast and articulate evidence of their culture. Indeed, among the most important works preserved in the museum is the Painted Sarcophagus of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa, found at Poggio Cantarello in Tuscany. The sarcophagus, made of painted terracotta, bears the name of the deceased on the lid, while the woman is depicted lying on a mattress with a pillow, holding an open mirror with her left hand and lifting her right hand to arrange her cloak. She wears a tunic with a high belt, an edged cloak and jewelry that includes a tiara, earrings, necklace, bracelets and rings.

The Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden, the Netherlands, also holds an extensive collection of works by the Etruscan people. Among the most important sections are those devoted to urns, statues from the Archaic period, sarcophagi, amphorae and gold jewelry. In this regard, the wealth of the Etruscans emerges especially along the southern coast, where the elite accumulated luxury goods of oriental origin. Indeed, thanks to their contacts with the Eastern world, the Etruscans learned refined techniques for making objects, importing Egyptian enamels, ceramic scarabs, worked ivory, carved bones, and expertly decorated ostrich eggs and precious jewelry.

The Etruscan section of the Louvre in Paris, on the other hand, presents an articulate overview of the people’s artistic and craft production. A few examples? Among the exhibits are belt buckles dated between 625-600 B.C. and 800-675 B.C. and numerous statuettes made between the fourth and third centuries B.C., including a votive statuette depicting the goddess Minerva (475-450 B.C.). The collection also includes tools and vessels for everyday use: handles of a shallow dish(patera) (325-200 B.C.), plastic and metal vessels(situlae) from the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C., examples of the technical precision and decorative variety typical of Etruscan art.

Among the most important works, however, is the Sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom dated 520 and 510 B.C., made of red clay and found in Cerveteri (one of the largest ancient necropolis in the Mediterranean: this is also where the Sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom now in the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome, very similar to the one in the Louvre, comes from), a symbol of Etruscan funerary art and the care devoted to the memory of the dead. Alongside the artifact, the collection also documents the evolution of pottery and artistic production in the ancient world. Examples include a small bronze flask dated 750-700 B.C.E., a chalice from 625-500 B.C.E. and jug-like vessels(oinochoe) from 600-575 B.C.E. The vase made around 560 B.C. by the Amasis Painter, on the other hand, coexists with an amphora from 590 B.C. attributed to the Gorgon Painter and another amphora from 540-530 B.C. signed by Exékias, among the most important masters of Attic ceramics. What then does the Louvre’s collection teach us? That the works housed within it reveal the deep cultural and artistic links between Etruria and the Greek world.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York , on the other hand, holds a large core of Etruscan art that illustrates the technical and decorative sophistication of the civilization between the 7th and 3rd centuries BCE. Among the artifacts are a group of jewelry dating from the early 5th century BCE and a bronze statuette depicting a young woman from the late 6th century BCE. Among the amber objects can be found a carved brooch datable to around 500 BCE. The collection also includes several bronze mirrors, including one from 350 B.C.E. and another with an ivory handle from the late 4th century B.C.E. There are also terracotta antefixes from the late 6th century B.C.E., goblets and vases (volute craters) of Greek origin used for mixing wine and water, as well as bronze and terracotta oinochoe vases, some with distinctive shapes such as a woman’s head, dating between the 6th and 3rd centuries B.C.E.

Bronze objects include the famous Monteleone Chariot, an ivory-inlaid chariot from the second quarter of the sixth century B.C., incense burner bowls(thymiaterion) and shallow bowls. Gold jewelry includes fibulae and gold rings decorated with animal motifs, some embellished with carnelian or rock crystal. Etruscan funerary art, on the other hand, is documented by alabaster and terracotta cinerary urns, dated between the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C., while bronze statuettes of young men belong to the 6th century and its end. Completing the collection are ritual and decorative accessories such as bronze incense burners, perfume spoons, gold and glass necklaces, and fibulae with plant or mythological motifs, evidence of the sophisticated craftsmanship and artistry of the Etruscans.

The Getty Museum in Los Angeles also holds a large collection of Etruscan and Attic artifacts documenting the life, art, and funerary rites of the Etruscan civilization. The museum’s collection includes both Etruscan and Attic fragments and objects: vases with overlapping colors, cups, black-figure and impasto vases, black-glazed vases, fragmentary footed dishes, bucchero goblets, and miscellaneous fragments. Attic red-figure vases are attributed to painters such as Syleus and the Marsyas painter and include chalices, rows, and panathenaic amphorae.

Funerary objects, on the other hand, include inscribed cippus, lidded cinerary urns, and funerary bed appliqués, along with buckles. The ornamental collection includes gold necklaces, disc pendants, pairs of earrings and ring fragments. There is also apair of candelabra with dancers from Vulci, statues of animals such as the wild boar, mythological figures including a clay vase(guttus) with a satyr’s head, and the statue of Hercules known as Lansdowne Herakles. The collection also features fragments of Attic vases from various periods, Greek, Roman and Etruscan gems and cameos, as well as Etruscan clay vases(stamnos) with red figures.

Also in the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland,Ohio , United States, are Etruscan masterpieces spanning from the 9th century B.C. to the Hellenistic period. Among the most outstanding works is a cista handle (a basket-shaped vessel intended for different uses) with bronze depictions of Sleep and Death, two winged deities in warrior garb carrying a helpless body dated 400-375 BC. Also notable is a statuette of a Kouros (600-480 BCE), a demonstration of Greek influence on Etruscan art. Visitors can observe supports for a shallow dish, such as one dedicated to Lasa (300-175 B.C.E.), and candelabra bases, including that of the Dancing Maenad dated 525-500 B.C.E., made of bronze with raised arms and a dynamic, harmonious posture. The collection also includes distinctive vases, such as the WildBoar Vase (700-500 BCE), decorated with incised geometric lines, and vase ornaments depicting banqueters or musicians from the 4th century BCE.

Among the votive figures and statuettes, on the other hand, we can find the male votive figure (3rd century B.C.), the statuette of a young woman dated 520-500 B.C., the female statuette (600-480 B.C.), and the statuette of Tinia. Among the funerary and decorative grave goods, on the other hand, the museum preserves mirrors engraved with mythological scenes, as well as pitcher jars(oinochoai) and clay vessels decorated with black or red figures, which document the technical sophistication and narrative capacity of Etruscan pottery (often with depictions of feasting, hunting or mythological episodes).

The collection also includes a wide variety of brooches, boat-shaped, spiral or straight, dating from the 9th century B.C.E. to the 1st century B.C.E., along with dog tags, pendants and jewelry such as pairs of earrings from the 3rd century B.C.E. Items of everyday and decorative use, such as incense burners and antefixes, are also present. And not only that. The passion for Etruscan art is also reflected in the works of modern artists. These include Edgar Degas ’s print entitled Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: the Etruscan Gallery, in which Degas depicts Mary Cassatt and her sister Lydia at the Louvre. In the scene, Cassatt observes an Etruscan tomb dated to about 500 B.C. (probably the Sarcophagus of the Spouses), discovered in Cerveteri, while her sister Lydia reads a guidebook. Alongside Degas, we also find Henri Matisse, who pays homage to Etruscan art with his 1940 oil on canvas Interior with an Etruscan Vase (Intérieur au vase étrusque), a work that inserts an ancient vase into a modern composition.

In contrast, the Etruscan-Italic and Roman collection at the Staatliche Museen in Berlin is presented as a heterogeneous collection of statuettes, vases and metal objects, the catalog of which was formalized in two phases. The first, between 2004 and 2007, was based onKarl Friedrichs’s inventory Geräthe und Broncen im Alten Museum (Tools and Bronzes in the Old Museum) of 1871, a text devoid of illustrations but crucial for assigning the catalog numbers still used today. Prominent among the main Etruscan works preserved are circular shields from the 7th century B.C.E., decorated with concentric motifs alternating human figures, animals, and geometric elements. The type of shields, produced mainly in Tarquinia (Viterbo), were in fact intended for ceremonial or representative uses. Several bronze handles and a mirror, also made of bronze, depicting a love scene complete the collection.

Finally, in the exhibition at the Danish National Museum in Copenhagen, a pair of bronze sandals dated between 500 and 300 B.C. are evidence of Etruscan civilization and its role in the development of Roman culture. As mentioned earlier, the Etruscans inhabited central Italy as early as the fifth century B.C., particularly in the region that the Romans would later call Tuscia. Their cities developed in close relationship with the surrounding landscape, between urban areas and necropolis, according to a spatial organization that profoundly influenced Roman town planning. Many of the paths traveled by the Etruscans were thus later transformed into roads by the Romans, demonstrating how deeply the foundations of their civilization were rooted in the experiences of earlier peoples.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.