Exactly seventy-five years have passed since Francesco Arcangeli wished the arrival of a “good day” for Simone Cantarini as well, “a name unknown to most, the name of a short-lived schoolboy of the far more famous Guido Reni.” And it is still difficult to argue that the Pesarese’s name came out of anonymity for most of the public. However, it is certain that since that 1950, Cantarini has had at least a couple of good and important days: the first in 1997, when Andrea Emiliani, at the head of a large group of scholars, organized within a few months a couple of important exhibitions (one in Pesaro, the other in Bologna) and sanctioned the definitive rediscovery of an artist who never knew any middle measures, either when alive or dead. The second is the exhibition at the Galleria Nazionale d’Urbino, curated by Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari, Yuri Primarosa and Luigi Gallo, which closes today and has set itself the stated goal of continuing this operation of distancing the figure of Simone Cantarini from the reflected light of Guido Reni (whose rival he would later become, moreover: it was in 1637 when Cantarini abruptly refused a correction on one of his altarpieces, the Transfiguration now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, by the master, who had also procured the commission for him, and a violent break-up ensued), in order to restore to him all that autonomy, all that quality, all that originality that is due to him, with the precise idea, Ambrosini Massari writes in the catalog, of “to present the artist [...] in his richness and variety of stylistic registers and poetics, a full participant in the most important occasions of his time for updating, and confronting the most advanced figurative culture on a vast scale, in close contact with some of the centers from which the most singular novelties radiated, such as Bologna and Rome, and not only.”

Simone Cantarini’s poor appeal also comes in part from Carlo Cesare Malvasia’s laconic and ambiguous assessment of his painting in the Felsina pittrice: “He was, in short, the most graceful colorist and the most correct draughtsman that our century has had and who has imitated Guido, than whom perhaps he was more amorous and gallant, if not so noble and well founded.” It is true that Malvasia, who also had known Cantarini during his lifetime (they were almost the same age and for some time were on very close terms), had tried not to be unbalanced, to compose a judgment that he must in all likelihood have felt was correct, balanced, and objective. Nonetheless, he had ended up sticking to Cantarini that label of a simple imitator of Guido Reni that, for centuries, he would never again be able to shake off, even though he continued to garner a certain, conspicuous consideration especially from that part of the critics who continued to cultivate a sincere, passionate appreciation of him. That Cantarini, however, beyond his gifts as a “gracious colorist” and “correct draughtsman,” was something more than an excellent pupil of Guido had already been established Francesco Arcangeli in 1950, in one of his pioneering essays, no longer than four pages, in which he attributed to the Pesarese an “ingenuity to produce a new beauty ’similar’, but not slavish, to that of Reni.” a feeling, Emiliani would later explicate in the catalog of the Bologna exhibition, “of melancholic beauty that had never entered within the walls of a formal academy, of a poetry of rhetoric, such as that of Guido Reni was on the contrary.” An interpretation not dissimilar, moreover, from that which Ambrosini Massari and Primarosa, having in mind the sacred paintings of Simone Cantarini, provided to visitors to the Urbino exhibition, speaking of an “elegiac” painting of which we have spoken extensively on these pages, a painting of looks and silences, a painting that transfigures the sacred into poetry of the soul far from the monumental emphasis of so much seventeenth-century painting. Cantarini is, however, a painter of contradictions, capable of a painting imbued with classical beauty, a beauty that reminded Arcangeli of ancient Greece, capable of a painting that was familiar with the idea of Raphael and the grace of Federico Barocci and was at the same time sensitive to the naturalism that, in the wake of the Caravaggio revolution, s’had spread in his native land, in the Marche of Giovan Francesco Guerrieri, in the Marche traversed by Orazio Gentileschi, and capable even of the lightning-fast and sudden intuitions that derive from contact with the works of a Carlo Bononi or a Guido Cagnacci, to name a couple of artists who certainly cannot be said to be Cantarini’s points of reference, but who left a stentorian echo in certain shining episodes of his production.

The main merit of the Urbino exhibition, without taking into account the unpublished and updated works, is therefore that of having presented in all its forms the radical, conscious, attentive, visionary, elegiac inspiration of’a versatile painter who, admittedly, has not yet achieved (and probably never will) the fame of a Guido Reni, much less that of a Caravaggio, but who finds much of his greatness in this ’borderline painting,’ we might say, original though not revolutionary and yet practiced with sublime quality, in this poetic of his, Emiliani wrote, “suspended on the dividing line between the ancient and the present, in the artistic and historical tramando to which this Italian province still feeds, and the surfacing of novelties that frequent, suggestive, bind themselves to appearances filled with the seduction of actuality.” One wonders if Simone Cantarini’s destiny should still be considered inextricably linked to that of a province, as vital and colorful as Emiliani intended it to be, and in particular to that borderland where, at the time of the Pesarese, the instances that crossed the Romagna plain starting from the Bologna of the Carraccis and those that came down from the hills of the Marche were measured: the Urbino exhibition gives, if anything, an account of the openness, the breadth of horizons of an artist who had been able to shape his language by taking advantage of what he had seen in Rome, Venice, and Bologna. The outcome will not make Cantarini a cosmopolitan painter: his production is, moreover, confined to a limited sphere and to a peripheral area (however, had he been Roman, Florentine or even Bolognese, however much Malvasia had tried to consider him a Felsine painter and not an oriundo, or had Urbino not become a periphery in the space of a very short time, when Simone was not yet twenty years old, we might have written a different story today: think of the esteem in which Federico Barocci is held today). But surely the images he left us are enough to ward off the risk that he might be considered a provincial artist.

The Urbino exhibition proceeds thematically rather than following the life of Simone Cantarini, as the 1997 Bologna exhibition had done, which to this day still remains the largest monographic exhibition on him, given also the fact that on that occasion a large corpus of drawings was displayed to the public (Cantarini was one of the greatest great draftsmen of the seventeenth century), which Ambrosini Massari and Primarosa deliberately excluded from the exhibition at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in order to focus solely on painting (those who wanted to get to know the ’graphic’ Cantarini, however, were able to see a selection of etchings on the second floor of the Ducal Palace, where some of his great paintings that are part of the permanent collection remain). A choice, that of constructing the exhibition itinerary by thematic nuclei, which insinuates itself into the groove of’A choice, that of constructing the exhibition itinerary by thematic nuclei, which follows in the wake of a rather widespread practice (unfortunately, in the opinion of the writer), and which certainly has its disadvantages and limitations, first and foremost that of not making it easy to understand the development (especially to those who do not know the painting of Pesaro in detail) of the path of an artist who did not have a linear path and who is certainly not the easiest, the most potable. The risk, for example, is that a distracted visitor will not realize how precocious the genius of Simone Cantarini was, since his astonishing Adoration of the Magi now in the Quadreria of Palazzo Magnani in Bologna is a work he made when he was roughly sixteen, seventeen years old, and is displayed, in what is perhaps the most exciting section of the exhibition, amidst things painted even much later: it will be worth remembering that until recently theAdoration was even considered a work from the very last phase of his activity (this is how Emiliani considered it: a product of Cantarini in his early thirties), but some recently discovered documents have made it possible to fix its dating to the early stages of his career. On the other hand, the thematic itinerary is useful on the one hand to show how Simone Cantarini was able to offer his clientele unexpected variations on the same subjects even within a very short period of time, and how intelligently permeable his painting was to everything that revolved around it.

And that Simone Cantarini was capable of absorbing everything is evidence from the works on display in the first section, centered on portraiture, that is, the genre in which the Pesarese trained, looking to the penetrating investigations of Claudio Ridolfi who was among his first masters, as is attested by the Portrait of Cardinal Antonio Barberini iunior in the Palazzo Barberini, executed when the artist was eighteen years old and which in Urbino is exhibited for the first time alongside two other portraits of Barberini, both attributed to Cantarini by Ambrosini Massari, A familiarity with the subject that Cantarini would later explore in greater depth on several occasions, even later in his career: suffice it to admire the delicate Allegory of Painting , where some reminiscences of Bononi can be felt, and especially the intense Portrait of Eleonora Albani Tommasi (which just this year was granted to the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche on loan from Intesa Sanpaolo), difficult to explain without assuming a certain frequentation of early 17th-century Roman painting, probably deepened in person with a trip to the Urbe Eterna.

The section on “sacred elegies” goes so far as to demonstrate (with a scenographic turnaround underscored as well by the installations, which leave the half-light of the first room and lead the public to a more illuminated) that Simone Cantarini was capable of looking even at the sweetest atmospheres of a Federico Barocci if not a Raphael (see the unpublished Holy Family or the Madonna and Child from the Caprotti Collection for a formidable summary of the most intimate Cantarini): it is in this second room that Simone Cantarini’s versatility is accounted for, his ability to fuse in an entirely personal and unparalleled synthesis “the more courtly voice of Guido Reni with the more earthly voice of post-Caravaggesque naturalism,” writes Ambrosini Massari, and not without sometimes getting carried away by themomentary enthusiasm for the achievements of some colleague, as can be seen when looking at the St. James in Glory in which the references to Guido Cagnacci are evident, for those familiar with seventeenth-century painting, specifically to his Magdalene Taken to Heaven that can be admired today in the two versions in the Pitti Palace and Munich. That synthesis mentioned above is instead to be appreciated, for example, in a painting such as the Madonna and Child in Glory with Saints Barbara and Terence, which Simone painted as an 18-year-old for the church of San Cassiano in Pesaro and in which s’even wanted to see a self-portrait of the artist (based on the match with theSelf-portrait that is exhibited in the first room), which would have given his face to the patron saint of his hometown: it is a work in which, Ambrosini Massari wrote in the 1997 exhibition catalog, “the difficult language of Bolognese classicism is [...] filtered by different stimuli, also of Emilian origin, but naturalist: Guerrieri on the one hand, Annibale Carracci and Ludovico [...] and Carlo Bononi.” The result of various contaminations is also the Immaculate Conception with Saints John the Evangelist, Nicholas of Tolentino and Euphemia, which looks to Savoldo’s Lombardy, to the atmospheres of Venetian painting, to the Marche of the usual Guerrieri and even, according to some, to the extravagances of Lorenzo Lotto. And all without ever risking pastiche, because Cantarini’s infinite modulations intervene on a solid score, formed in the Marche region but germinated and finally fine-tuned in the Bologna of Carracci and Guido Reni, and the result is a personal synthesis, which certainly knows ups and downs, but which is recognizable because of that finesse of execution, that expressive intensity, that tension that can be felt behind each of its figures, behind each passage from light to shadow, almost as if something were about to come to disrupt a stillness pregnant with restlessness, which rests on a precarious balance.

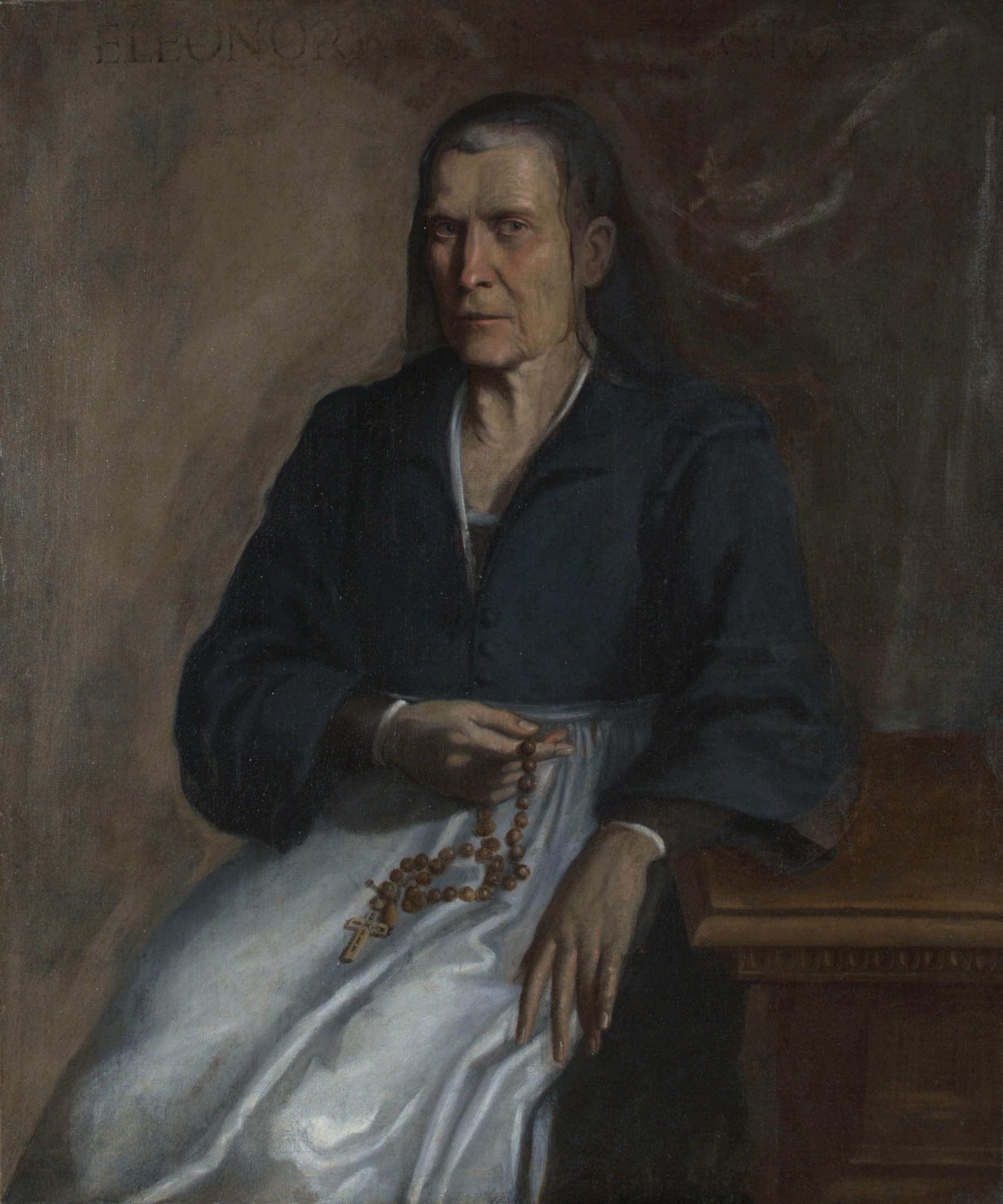

If the room that gathers all the portraits of saints offers an overview of the more realist Cantarini, closer to Caravaggio’s painting, sometimes filtered by Guerrieri (so it seems when looking at the Renegade of St. Peter), sometimes instead mitigated by theRhenish idealism (as is the case in the St. Jerome of the Bemberg Foundation in Toulouse), but never fully adhering to Merisi’s manner (a St. Jerome by Bartolomeo Manfredi who’is instead all steeped in Caravaggio’s painting), the following chapter offers the audience a lunge into the artist’s creative process, and in particular his use of painting, of the same work, “on the one hand perfectly finished, clear and luminous versions, on the other hand more introspective and apparently unfinished proofs, often conducted in brown and earthy tones” (so Yuri Primarosa). In the exhibition, three pairs of paintings have been paired to compose curious diptychs that demonstrate this unique way of working: the comparison between the two versions of St. Jerome reading in the desert, in particular, perhaps more than any other reveals, on the one hand, the experimentalism of a painter who was always in constant search of novelty, and on the other hand also the restlessness of an artist with a sensibility that today, to our eyes, appears to be of astonishing modernity, a modernity that lives and pulsates especially in the earthier version, with those coruscating brushstrokes, with the landscape that seems to be left in the state of sketch, with the whole that conveys almost a sense of unfinishedness.

Variations on the alternation between classicism and naturalism again animate the penultimate room of the review, where the juxtaposition between the very polished Holy Family of the Colonna Gallery and the rougher one of the Corsini Gallery stands out, again on the theme of “diptychs,” and where a dialogue with Valentin de Boulogne is also proposed in the comparison between the two Saint John the Baptist: an unpublished one by Cantarini, the derivations of which were hitherto known (credit therefore to Primarosa for having found the prototype). The finale is instead reserved for productions with mythological and profane themes: of particular interest, in this last section, in addition to the recently attributed unfinished Philosopher with Compasses (it appeared at auction only nine years ago, with generic attribution to a 17th-century artist), is the presence ofHercules and Iole, a “rediscovered” masterpiece, to use the curators’ own adjective, which is being shown to the public for the first time. “Rediscovered” because it is, arguably, a painting cited and celebrated by Carlo Cesare Malvasia as a work even capable of surpassing Guido Reni and even Raphael, “so fair, so graceful, that one cannot look at it without danger of emotion,” a work that “must be greatly praised.” It is, indeed, one of the most exquisite products of the latter part of Simone Cantarini’s career, one of his subtlest, most delicate interpretations of Reni’s idealism, as well as one of the Urbino exhibition’s highlights and greatest novelties.

It will be appropriate to point out that one of the keys to understanding this exhibition is offered by its subtitle: “A Young Master between Pesaro, Bologna and Rome.” This is a specification of rare finesse, completeness and intelligence, since it includes all the novelty of the gaze that this exhibition, albeit with a path that is not the most immediate, has turned to Simone Cantarini. “Young,” because the theme of his precocity is inescapable. “Master,” so that we stop considering him a mere product of the Reni workshop and begin to recognize his stature, which is more properly that of an autonomous master, an independent artist, a painter who left on the painting of his time aecho admittedly territorially limited, but nonetheless present, from direct pupils such as Lorenzo Pasinelli and Flaminio Torri to the point of fascinating, decades later, even a Donato Creti and a Giuseppe Maria Crespi, that is, the two stars of Bolognese painting in the early eighteenth century. “Pesaro, Bologna and Rome,” finally, are something more than mere geographic coordinates, something more than the stages of Simone Cantarini’s short journey: they are proof of the breadth of his views, they are the cardinal points that make it possible to remove him from the dimension of a provincial artist.

Perhaps, however, Simone Cantarini’s greatness is to be found elsewhere. In those sketches that foreshadow a gaze that transcends his era, in those doubles with dim and earthy tones, in that restless frenzy that characterizes all his activity, in that continuous, perennial dissatisfaction. The Urbino exhibition had the merit of not indulging too much in biographies or romanticisms, but it is inevitable to think of the Pesarese’sSelf-Portrait as a kind of epitome of his greatness. Simone Cantarini seems to be all there, in that unfinished painting in which he depicts himself with sunken eyes that convey all the confidence that would lead him even to excess, with those brush swipes that summarily define the sleeves of the giuppone from which emerge two snow-white linen cuffs to guide the gaze to the slender, tapered, ringed hands that clutch not the brush and palette, as conventions wanted, but the pencil and notebook, a symbol of creativity, of inquiry, of research. A sign that did not want to be recognized on the basis of a tradition, but claimed, and even proudly, that freedom that is proper to great artists. There is perhaps then a hope that one day Simone Cantarini’s fame may equal that of Guido Reni and other artists known not only to the circles of specialists: but this flame will necessarily have to pass through the recognition of this freedom of his, of this sensibility of his that seems so modern to us today.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.