Entitled Guercino . The Painter’s Trade the exhibition that the Royal Museums of Turin are dedicating to Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri; Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666) and hosting at the Sale Chiablese from March 23 to July 28, 2024. The exhibition, organized in collaboration with CoopCulture and Villaggio Globale International, aims to represent a significant moment in the context of studies on the work and figure of Guercino, especially after the reopening of the Pinacoteca Civica di Cento. Curated by Annamaria Bava of the Musei Reali and Gelsomina Spione of the University of Turin, with the collaboration of a scientific committee composed of Daniele Benati, David García Cueto, Barbara Ghelfi, Francesco Gonzales, Fausto Gozzi, Alessandro Morandotti, Raffaella Morselli and Sofia Villano, the exhibition explores the painter’s craft in the 17th century through the figure of one of the major protagonists of the period. Featuring masterpieces by Guercino and other coeval artists, the exhibition aims to offer a glimpse into the profession of the painter in the seventeenth century, including the challenges of the trade, production systems, workshop organization, market dynamics and commissions.

More than one hundred works by Guercino and other artists, from over thirty major museums and collections, are displayed to create a comprehensive fresco of the art system in the seventeenth century. This exhibition also includes the cycle of paintings commissioned in Bologna by Alessandro Ludovisi, the future Pope Gregory XV, brought together for the first time in four hundred years. Thanks to Guercino’s structured workshop and the rich documentation available, the exhibition offers a detailed analysis of the life and work of seventeenth-century painters. The works on display, including two previously unpublished paintings from private collections, offer significant evidence of Guercino’s life and creative process, showing his relationships with a wide range of patrons and his influence on the artistic scene of the time. The exhibition is divided into ten thematic sections that allow for an in-depth exploration of Guercino’s life and work, offering comparisons, parallels, and significant evidence.

Guercino’s self-portrait from the Schoeppler Collection in London, depicting him in his early 40s with the tools of his trade, opens the exhibition itinerary. This intimate and private work, not recorded in his famous Book of Accounts, offers a snapshot of Guercino’s character, both proud and simple. His stage of artistic formation is strongly influenced by his study of the works of the great masters and his encounters with prominent figures. Ludovico Carracci represents one of the main points of reference for Guercino, both in Bologna and Cento, as evidenced by the precious oil on copper with the Annunciation from the Strada Nuova Museums in Genoa. On the Ferrara side, before his journey to Venice, Guercino was influenced by artists such as Scarsellino and Carlo Bononi, both of whom are featured in the exhibition itinerary. In addition, the exhibition includes two important early works by Guercino: the small panel with The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine, on loan from the Credem Art Collection, and the altarpiece from the Renazzo parish church with A Miracle of St. Charles Borromeo. The first section(How a painter is formed: the comparison with the masters) delves into the theme of the painter’s training, for which not only the apprenticeship in the workshop of an older master counts, but also the study of the artistic production of the context in which he lives. Cento was politically dependent on Ferrara, but was part of the diocese of Bologna: the young Guercino gravitated between these two centers during his formative years. As Malvasia recalled, the painter often visited Bologna to observe the works of the Carracci and make memories of them. However, the attention to detail in nature, typical of the Bolognese masters, was already evident in his own city, where in 1591 the Holy Family with St. Francis and Two Donors of Ludovico, now on display at the Pinacoteca Civica di Cento, had arrived. The young artist’s training also included Ferrara influence, with the notable 16th-century model of Dosso Dossi and the works of Scarsellino and, above all, Carlo Bononi. His training was completed with a trip to Venice in 1618, where Guercino was able to directly confront the works of great artists of the sixteenth-century season such as Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese.

Later, Guercino confronted everyday reality and showed a marked inclination toward landscape (second section, Representing Reality: the Landscape) in line with other artists such as Annibale Carracci, Domenichino, and Agostino Tassi. The exhibition highlights this period through important drawings by Guercino from the Royal Library in Turin and the wall paintings of Casa Pannini, created by the young painter in Cento between 1615 and 1617 with collaborators. In addition to the comparison with the works of other artists, both in the workshop and in the training context, the direct relationship with reality could play a key role in a painter’s growth. Guercino was an extraordinarily keen observer, endowed with a distinct vocation for interpreting nature and everyday scenes. The artist followed the pioneering work of Annibale and Agostino Carracci, although his production of landscapes seems to be concentrated mainly in his early period. The Book of Accounts, compiled from 1629 until Guercino’s death, no longer records landscape paintings: according to the laws of the market, the incessant demand for altarpieces and history paintings led to the gradual exhaustion of the production of small-format works. However, the extraordinary number of drawings of views of the city’s environs attests to the fact that graphic landscape production accompanied the entire span of Guercino’s life, confirming what his biographer Cesare Malvasia tells us, according to whom the painter drew at all times of the day, even in the evening after dinner, while he was entertaining family members.

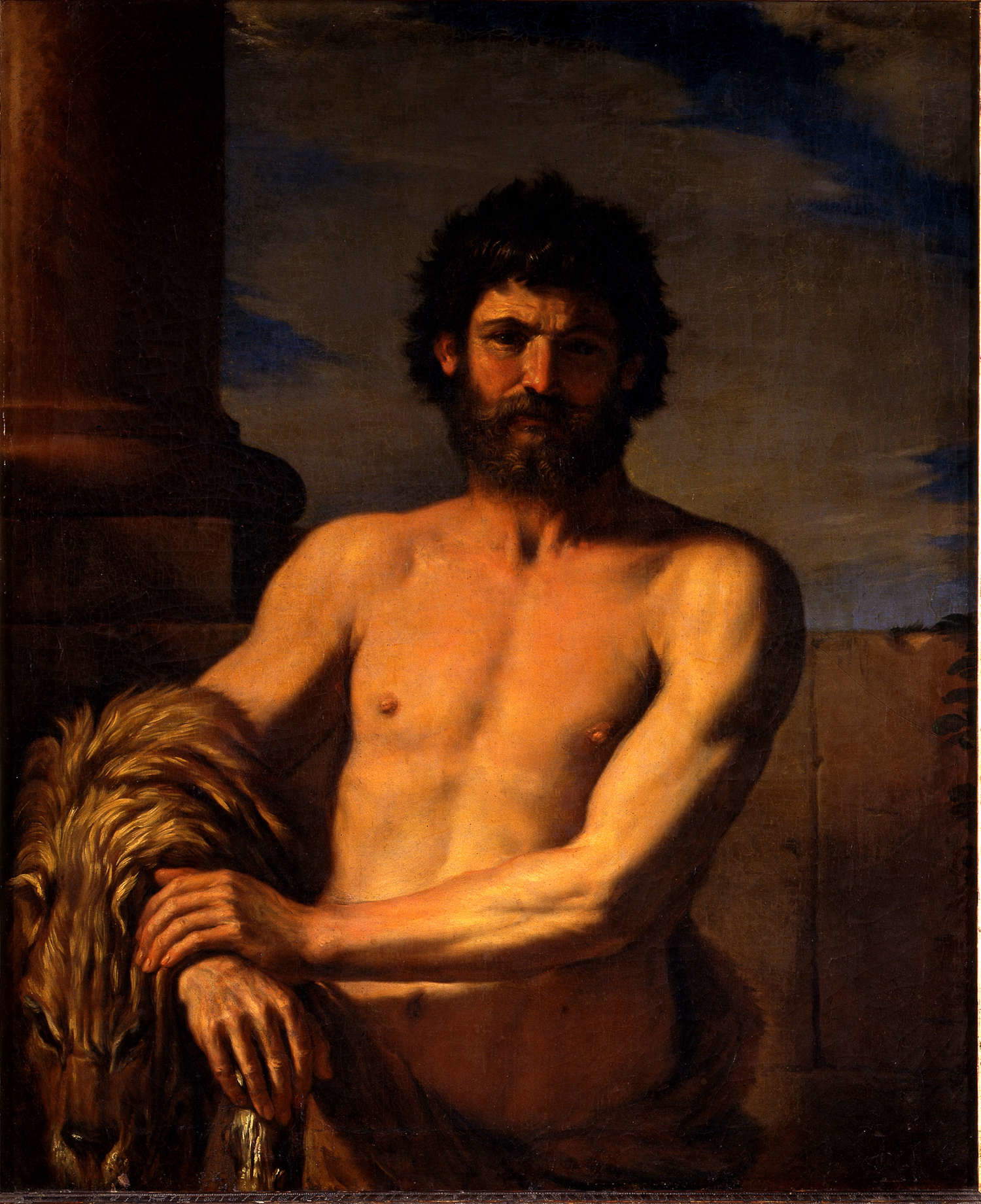

The next phase is marked by Guercino’s opening of theAcademy of the Nude in 1616, thus consolidating its fame at home and making it a point of reference for many young artists (third section, From pupil to master: the Academy of the Nude). In the training of artists, a crucial step was the practice of drawing and the study from life of the human body, often conducted within private academies led by more experienced painters. The young Guercino, too, honed his skills through drawing on life models. In 1616, a few years after the start of his career as a painter and by then well-established in his native land, Guercino established aNude Academy in Cento, thanks to the availability of two rooms offered by his friend Bartolomeo Fabbri, modeling it on the example of the Bologneseacademy of the Carracci or their pupil Pietro Faccini. The school’s success was immediate, as demonstrated by the considerable number of young people who, according to Malvasia’s account, flocked “from Bologna, from Ferrara, from Modena, from Rimini, from Reggio and even from France.” This positive response prompted Guercino, at the suggestion of Father Mirandola, president of the convent of Santo Spirito and one of the artist’s earliest and most fervent supporters, to transpose his drawings into an anthological manual intended for young artists, entitled The Principles of Drawing. The manual, illustrated by engravings by Oliviero Gatti of Piacenza, was published in 1619 with a dedication to the Duke of Mantua Ferdinando Gonzaga. The exhibition also highlights the intense dialogue between the master’s nude drawings and the painting of Saint Sebastian being cared for by Irene (1619), from the Pinacoteca in Bologna. This work, requested by Jacopo Serra, cardinal legate of Ferrara and Guercino’s refined patron, is distinguished by the lively and intense naturalism that characterizes the master’s poetics, capable of transforming the sacred event into a scene of everyday life.

Before exploring the theme of the workshop and its dynamics, the exhibition traces the stages of the painter’s affirmation and the geography of commissions, fundamental in the career of every artist (fourth section, The painter’s affirmation: travel, relationships and commissions).

In this context, the figure of Alessandro Ludovisi, archbishop of Bologna and from 1621 Pope Gregory XV, takes on particular relevance. Ludovisi had already met Guercino between 1617 and 1618 through the mediation of Father Antonio Mirandola, a great promoter of the artist from Cento, and the appreciation of Ludovico Carracci, who was thunderstruck by the young artist’s painting. Ludovico Carracci was called upon by Archbishop Ludovisi to estimate the cost of the commissioned works. And it was precisely between 1617 and 1618 that Guercino created four large canvases for Alessandro Ludovisi and his nephew Ludovico, works that are exceptionally reunited after four centuries in the Turin exhibition: Lot and the Daughters from San Lorenzo in El Escorial, Susanna and the Old Men loaned by the Prado Museum, The Resurrection of Tabita from the Uffizi Galleries-Palazzo Pitti, and The Return of the Prodigal Son from the Royal Museums. The latter painting does not appear in Alessandro Ludovisi’s inventory of 1623, but it is already described in the Savoy collections in 1631. There is speculation that it may have been a targeted gift to Duke Charles Emmanuel I from Ludovisi, who was appointed apostolic nuncio to the court of Turin in 1616 to settle disputes between the House of Savoy and Spain.

The Ludovisi cycle of canvases marks a turning point in Guercino’s career: with the accession of Gregory XV to the papal throne, the artist moved to Rome for a few years, where he received very important commissions in the papal capital. Indeed, from 1629, Guercino’s Account Book provides a detailed list of recipients of much of his artistic output. These include members of the curia, the local petty nobility and a wide representation of the bourgeoisie of Cento. To these are added commissioners from other regions and countries, demonstrating the international prestige attained by the artist. Illustrious names such as Queen Maria de’ Medici of France, Charles I of England, Francesco I d’Este Duke of Modena, the Gonzaga, the Savoy, the Medici, and many other European lords commissioned works from Guercino, highlighting his growing success and appreciation in the international art scene. These commissions testify to the variety of commissions that helped consolidate the artist’s fame, including paintings both locally commissioned and requested by the most prestigious courts of the time. Significant works from this period include the splendid canvas with Venus, Mars and Love (1633) in the Estensi Galleries, commissioned for Francesco I d’Este and included in the decorations of the Chamber of Dreams in the Ducal Palace in Sassuolo. Another example is Apollo escorting Marsyas (1618) from the Pitti Palace, an intense work that Malvasia recalls was executed for the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Again, the Assumption (1620), once in the Church of the Rosary in Cento, occupies a prominent place, as the painter was particularly attached to this work. Also extraordinary is the presence of the monumental Madonna of the Rosary altarpiece from the church of San Domenico in Turin, which had not been seen up close since the late 1660s. This work testifies to Guercino’s connection with the Savoy duchy and his artistic influence in the region.

We then move on to the fifth section(In the artist’s workshop: nature and posed objects) dedicated to the workshop directed by Guercino, the result of the collaboration between the Barbieri and Gennari families (first in Cento and from 1642 in Bologna), which was extremely organized, with roles and methods that represented excellent examples of the artistic system of the time. Guercino’s brother, Paolo Antonio Barbieri, specialized in paintings with “still” subjects, as evidenced by the Natura morta con bottiglia, frutta e ortaggi (Still Life with Bottle, Fruit and Vegetables ) in a private collection and the Natura morta con paramenti vescovili e argenti (Still Life with Episcopal Vestments and Silver ) in the Pinacoteca di Cento. Within these works, the natural elements were often already pre-arranged, and Guercino intervened by adding figures only at the end, as in the case of the fascinating “Ortolana,” completed by Giovanni Francesco in 1655, six years after the death of his brother, author of the beautiful baskets of fruit and vegetables. Roles within the workshop were well-defined: Guercino is a “figure” painter, while Paolo Antonio deals continuously with, as mentioned, “still” subjects, intervening for this specific aspect in Giovanni Francesco’s paintings as well.

The exhibition also offers a number of juxtapositions to make evident the practice of the reproposition of models and the use of a repertoire of inventions (sixth section, The creative process: invention, the reproposition of models, the organization of the workshop). For example, two versions of the God the Father from the Galleria Sabauda and the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna (both 1646) are exhibited, placed next to the Immaculate Conception from the Pinacoteca Civica in Ancona (1656), which features a similar figure of the Eternal in the sky. Another comparison is between St. Matthew and the Angel, a masterpiece from the Capitoline Museums (1622), and the coeval St. Peter Freed by an Angel, one of the prestigious loans from the Prado Museum.

In addition, a series of precious drawings by the Cento artist tells of the creative process and the fundamental moment of invention through graphic work. Drawing within the workshop is not just an exercise of study, but constitutes a crucial phase in the invention, design and refinement of the work through different iterations. It also enables the transmission of artistic memory and reuse by students. The Inventory of the Goods of the Gennari House, compiled in 1715 after the death of Benedetto, Guercino’s favorite nephew and son of his sister Lucia, lists nearly 5340 sheets, more than half of which belong to the workshop leader himself. In the process of making a painting, Guercino used to produce a large amount of graphic proofs: an emblematic example is the altarpiece with the 1620 Vestizione di san Guglielmo, preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, for which he made as many as 23 preparatory drawings. Guercino also tended to draw on his repertoire of inventions, replicating them by adding variations or adapting them to different subjects. Moreover, the production of copies was of strategic importance, carefully managed by the master to prevent replicas from circulating before the release of the original. The organization of the workshop, led by Guercino together with his brother and with the collaboration of the Gennari family, reached its peak with the move to Bologna in 1642. This move came at a time when Cento was threatened by the Castro War and the sudden disappearance of Guido Reni gave Guercino the opportunity to assume a predominant role in the art market.

Guercino

Guercino

The logic of the market was not foreign to Guercino and his enterprise, and the “price list” varied according to the type of figures, the size of the canvas, and the use of precious pigments (seventh section, The Market and the Price of Works). Guercino’s main competitor in the Bolognese market was Guido Reni, whose San Giovanni Battista in the Galleria Sabauda is shown. Testifying to the high cost of the works made by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri with the precious lapis lazuli and the higher price of paintings with whole or multi-figure figures are the Saint Francis Receives the Stigmata (1633) granted by the Diocese of Novara, or some of the important works in the Savoy collections such as Saints Gertrude and Lucretia (1645) and the Blessing Madonna (1651). For the analysis of the market and economic value of the works, a very important tool are the account books kept in the artists’ workshops. Guercino’s Book of Accounts, currently preserved in Bologna at the Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio, from the year 1629 onwards painstakingly records the honorific title and name of the patrons, the provenance, the subjects of the paintings and the total expenditure converted from ducatoni to scudi. After Paolo Antonio’s death in 1649, the book was continued by Guercino himself and other workshop collaborators until the master’s death in 1666. The Book reveals the breadth and importance of the atelier’s production and its rigid system for setting the price of works: a predetermined cost for each whole figure, for a half-figure, or for a head; a price list that was adjusted according to clients and intermediaries. The choice of colors also influenced the price, with some particularly expensive and prestigious pigments, such as lacquers and lapis lazuli, whose additional cost is noted.

The last three sections of the exhibition are devoted to some of the themes and subjects that were most adherent to the reality of the time or particularly successful and therefore most investigated by the painter and workshop. This is the case of the scientific innovations related to the revolutionary Galilean thought, which ignited the interest of patrons, intellectuals and artists, including Guercino (eighth section, The world around the painter: science vs. magic). In the early seventeenth century, the importance of the revolution of Galilean thought involved patrons and artists, finding reflection in figurative production. Guercino also dwelt on this theme in works commissioned by the Medici, which feature Endymion and Atlas. In antithesis to Galileo’s modern science was the theme of magic and witchcraft, which seemed equally to attract the painter’s interest, as some of his drawings show. With a mixture of irony and skepticism, the master from Cento depicted witches, magicians, devilry, and spells (for example, The Magician Brumio). This context was also influenced by widespread Protestant dissent, even in small and very Catholic Cento, where inquisitorial trials were taking place for suspected Lutheran sympathies, possession of necromantic books or spells.

Then, The Grand Theater of Painting (ninth section) presents other masterpieces, including The Return of the Prodigal Son (1627-28) from the Galleria Borghese from the Roman Lancellotti collection, or Amnon and Tamar from the Galleria Estense in Modena. The Baroque is par excellence the theatrical era in which the representation of the affections becomes a central theme of artistic practice and theory. The theatricalization of painting is achieved by choosing a compositional cut that offers a close-up view of events and encourages the viewer’s involvement, with the accentuation of gestures and expressions. The characters act as if on a proscenium, with perspectives and stage apparatus amplifying their stage presence. This approach to theatrical painting was particularly congenial to Guercino, who stood out both when staging a single figure and when depicting a choral episode: his compositions appeared influenced by modern melodrama. Moreover, the attention to detail in the clothing and props, described in a naturalistic manner, gave the representations a sense of tangible reality, contributing to an even more engaging visual experience for the viewer.

Finally, the tenth section(A Theme of Success: Sibyls and “Femmes fortes”) is a striking roundup of great heroines of myth and history, strong women who convey courage, dignity, intelligence, and who close the exhibition. These are characters that Guercino helped to eternalize in iconography and imagination: the Sibyls (with a comparison of four different depictions), Diana, Lucretia and Cleopatra, the latter being the protagonist of a work at the Strada Nuova Museums in Genoa, imposing in size, and engaging in sensuality and modernity.

Days and opening hours: Tuesday through Sunday 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tickets: full exhibition €15, reduced exhibition €13 (groups with reservations, teachers, 18 - 25 years old, exhibition partner conventions), reduced exhibition €7 (visitors 12 to 17 years old), integrated exhibition + royal museums full €25, integrated exhibition + Leonardo full €25, royal tour full €30 (exhibition + royal museums + Leonardo), reduced royal tour €15 (18-25 years old). Free for children 0-11 years old, Piemonte museum season ticket, Torino Piemonte Card, Royal Pass, 1 escort for disabled; journalists; MiC employees; 2 escorts for school groups; ICOM members). Online exhibition ticket presale €2, exhibition group shift reservation €15, exhibition school shift reservation €10. Information and reservations t +39 0111 9560449 info.torino@coopculture.it (groups: tour@coopculture.it, schools: edu@coopculture.it) - www.coopculture.it - www.museireali.beniculturali.it

|

| Turin, at the Royal Museums the major exhibition on Guercino with international loans |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.