It is one of the most important discoveries of recent times: theEcce Homo that was about to go to auction in Madrid at Ansorena (story here) and was blocked before the sale because it was recognized by several scholars as a possible autograph by Caravaggio. Coming out in favor of the name of Michelangelo Merisi (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) at the moment were Massimo Pulini, author of an already much-discussed essay published in the aftermath of the news spread, and Maria Cristina Terzaghi (usually very cautious and prudent in formulating attributions). According to Terzaghi, the possibility that this is a work by Caravaggio emerges from comparisons with other autograph works by Caravaggio, from the hands of Pilate that reveal the same use of gestures present in the Madonna of the Rosary in Vienna, from the overlapping of planes (the play of perspective between the invention of Pilate leaning out from the balcony, the figure of Christ and the soldier putting his cloak on his shoulders), and from the matches between the head of Christ and the Neapolitan works of the Lombard artist.

We reached out to Rossella Vodret, a scholar among the leading experts on Caravaggio, to get her opinion on the discovery, always keeping in mind that these are only first impressions, that the work is in a state of preservation that is far from optimal, and that it will need to be better evaluated after at least one cleaning and after scientific studies. Rossella Vodret has written many scientific essays and several books on Caravaggio (including the volume, published by Silvana Editoriale, with the complete works of Caravaggio), as well as having curated exhibitions on the great Milanese painter: the last one, Dentro Caravaggio, was held at Palazzo Reale in Milan between 2017 and 2018. The interview is edited by Federico Giannini.

|

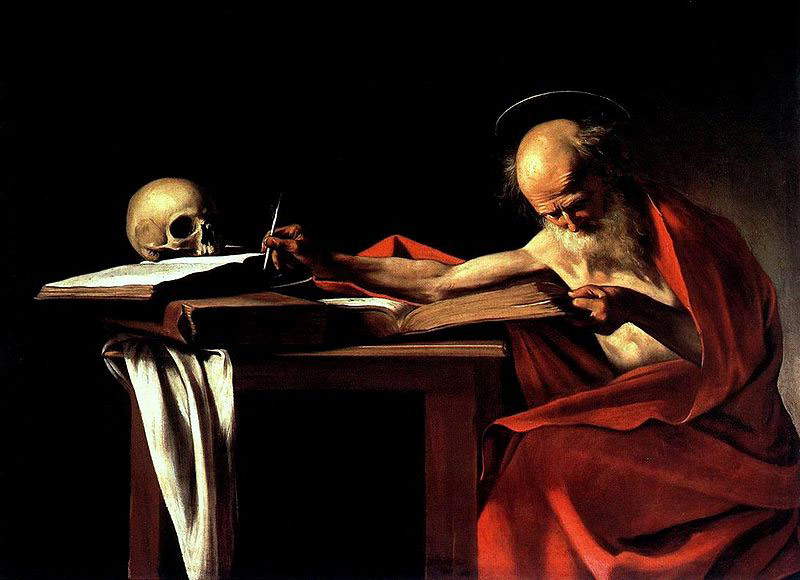

| Caravaggio (attr.), Ecce Homo (oil on canvas, 111 x 86 cm) |

FG. Dr. Vodret, what do you think of this painting?

RV. I first saw this work a few days through a photograph that Keith Christiansen sent me. As soon as I saw it, I jumped in my chair, which I don’t often do. It is true that the work is very dirty, so it is difficult to give opinions without seeing it and examining it live, preferably after a cleaning and without diagnostic investigations being done. But there are some elements that struck me immediately, first of all the face of Pilate so intense that he addresses himself directly to the viewer, with a gaze so piercing and sorrowful that it engages us emotionally in the action that is taking place (I at least had this feeling). Pilate’s gaze has the function that objects normally have in Caravaggio’s paintings: he often inserts some element in the foreground that tries to invade the viewer’s space, precisely to create the emotional relationship with the viewer and break down the wall between real space and painted space. In this case there are no objects, there are Pilate’s eyes, but they have an even greater immersive effect. By the way, I immediately had the feeling that the figure of Pilate was a late self-portrait: we see an aged Caravaggio, slimmed down compared to the youthful self-portraits, however, in my opinion it is him, I don’t have many doubts.

What, in addition to those you have already mentioned, are the elements that could make us think of Caravaggio?

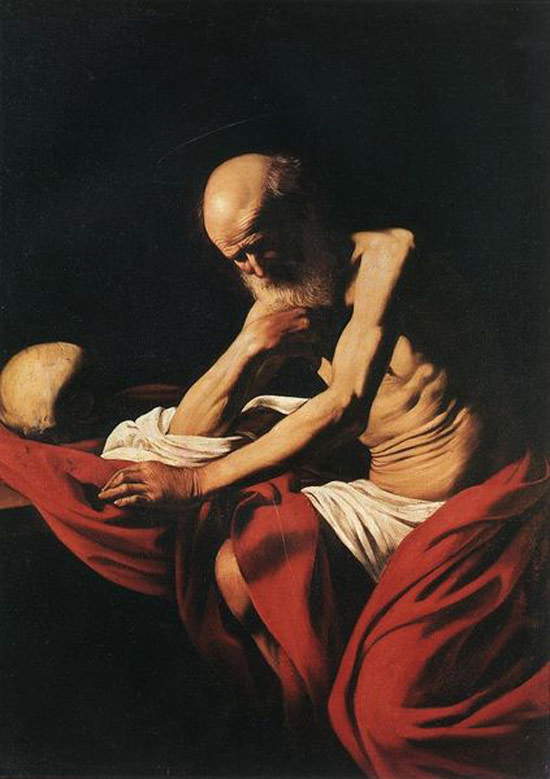

Despite all the reservations, due to the truly dramatic state of preservation, there are elements that jump out at you, despite the patina of dirt clouding the painting: first of all, the strength of this composition, all centered on the central figure of Christ in full light (and by the way with the ingenious invention of Pilate’s dark fifth that makes it stand out even more), the construction of the draperies, the strong structure of the hands, with a flash of light on Pilate’s thumb nail, which attracts the eye and is an element often used by Caravaggio, the white brushstrokes under the lower eyelid of Pilate’s eyes, the making of Christ’s eyes and mouth, which are very similar to those of the Borghese David. Then there are further observations regarding the execution technique, made visible thanks to an HD photo that was sent to me. I’m referring to a number of executional peculiarities specific to Caravaggio, such as the full-bodied zig-zag white lead sketches that the artist uses especially from 1605 onward and that are found in several works, such as the Saint Jerome Borghese, the Saint Jerome of Montserrat, and the Flagellation of Capodimonte. They are very particular sketches through which the painter fixes on the dark preparation of the canvas the points at which to place the areas of maximum light. It is a feature that, until now, I have not found in other painters. In theEcceHomo there are points the zigzag sketches on Christ’s chest, shoulder and arm, all in full light. The etchings are also his, although we know by now that etchings are done a bit by all artists of the period, but these are perfectly compatible with those we find on Caravaggio’s autograph paintings.

|

| Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath (1609-1610; oil on canvas, 125 x 100 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Caravaggio, Penitent Saint Jerome (1605-1606; oil on canvas, 112 x 157 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Caravaggio, Saint Jerome in Meditation (1605; oil on canvas, 118 x 81 cm; Montserrat, Museum of the Monastery of Santa Maria) |

|

| Caravaggio, Flagellation of Christ (1607; oil on canvas, 286 x 213 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, on deposit from the church of San Domenico, property of the Fondo Edifici di Culto - Ministero dellInterno) |

So is there a good chance that this time it is actually a work by Caravaggio?

I can say that, frankly, I don’t often get to evaluate a work without seeing it in person and in this state of preservation, and at the same time having all these elements that lead me to think that there is a good chance that it is a work by Caravaggio.

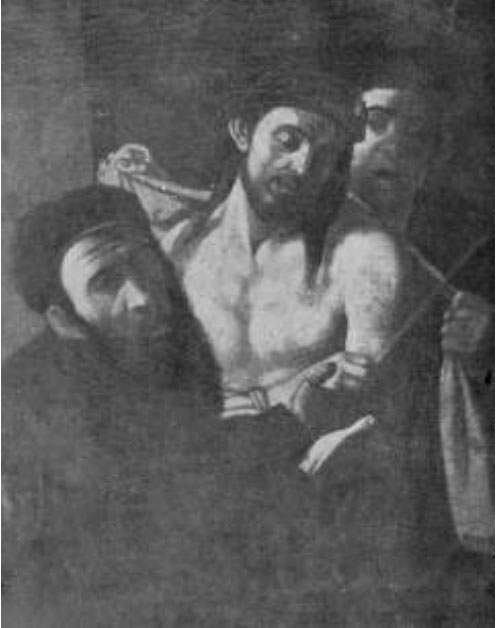

Incidentally, in the famous essay onEcce Homo in Genoa that Roberto Longhi published in 1954, a work identical to the one in Madrid was presented, although of lesser quality (at least judging from the photos). Would the fact that copies exist therefore further support the possibility that the Spanish painting is by Caravaggio?

Undoubtedly. There are many derivations from Caravaggio, it is clear that this was probably a well-known painting: especially in Sicily there are various derivations. The Genoa painting itself, which is clearly not his, suggests that it is a derivation, with variations, from this original. Indeed, this diffusion of the model is one element that goes to confirm that the painting was well known and was a model and, at the same time, its possible authorship.

|

| The work published as a derivation from Caravaggio in Longhi’s 1954 essay |

|

| Caravaggio (?), Ecce Homo (c. 1605-1610; oil on canvas, 128 x 103 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco) |

What can we say instead about the provenance?

Many have linked this painting to the Massimo commission in 1605 (the alleged competition, which, in my opinion, never actually took place: it is an a posteriori construction by Cigoli’s nephew, the artist who turned out to be the winner). However, I am convinced that the work does not have a Massimo provenance, although Bellori mentions an Ecce Homo from the Massimo collection that would have been taken to Spain. But the Massimo painting is mentioned in the inventories, without the author’s name, as a “large painting,” so I do not think it is possible to identify it with the Madrid canvas, which is certainly not large. And the one that has been recalled in these hours, theEcce Homo from the Lezcano collection mentioned in 1631, is also a “large painting”: the one in Madrid measures only 111 cm in height, so objectively it cannot be said to be “large.” Instead, a proposed provenance from the collection of García de Avellaneda y Haro, Count of Castrillo, who was viceroy of Naples between 1653 and 1659, seems to me more correct. We know from an inventory of his collection in 1657 that he owned two original paintings by Caravaggio: a Salome (the one in the Royal Palace in Madrid), and an Ecce Homo with soldier and Pilate that measured five palms, a measurement very close to the size of this painting. Paintings that, when his tenure ended, the viceroy took back to Spain. Then again (this is something I am studying just these days and so I am glad to mention it) the paintings by Caravaggio that were in Naples after his death must have been quite a few, because reading well the documents and especially the letters of Diodato Gentile [bishop of Caserta between 1604 and 1616 and apostolic nuncio to Naples between 1611 and 1616, ed.] to Scipione Borghese published by Vincenzo Pacelli, it is clear that Caravaggio, leaving by felucca to return to Rome, had brought many paintings with him: They were his pass to return to Rome and to thank all those, beginning with Scipione, who had contributed to his pardon. Diodato Gentile, in a letter dated July 29, 1610, a few days after Caravaggio’s death, complains saying that when the felucca had returned to Naples he had brought back only three paintings. From this statement it is clear that the paintings must have been many more. Moreover, also in July 1610, the viceroy of Naples wrote to the Spanish garrison in Tuscany asking for back all the effects that Caravaggio had left there [Porto Ercole at the time was part of the Stato dei Presidi, ed.] and in particular the paintings. So it is clear that these paintings existed: to understand where they ended up will require further study.LEcce Homo could have been one of these lost paintings....

To conclude: at this point, in case the Spanish painting was indeed by Caravaggio, a problem would open up about theEcce Homo in the Palazzo Bianco in Genoa.

I actually never believed that the EcceHomo in Genoa could be a work by Caravaggio. I even attended a conference in Genoa where I had the opportunity to study it in depth: there was no possibility, in my opinion, that this canvas could be a work by Caravaggio [ed. note: here Rossella Vodret’s misgivings that emerged from the conference].

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.