Fausto Gilberti (Brescia, 1970) is a painter and draftsman, one of the most appreciated on the contemporary Italian scene, as well as an author of children’s books, which he writes and illustrates. Gilberti studied at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts and began his career in the 1990s. Over time he became famous for his stylized characters, dazed creatures with big eyes, made with a few black strokes, which stand out on white sheets, with settings reduced to the bone. Throughout his career he has won the 2004 Acacia ti fa volare Prize and the 2007 Cairo Prize, exhibited in several solo and group exhibitions in Italy and abroad, and published several illustrated books: famous the series of books in which he narrated artists... that the public dislikes, such as Marcel Duchamp, Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni, Marina Abramovic. He lives and works in Brescia. In this conversation with Gabriele Landi, Fausto Gilberti tells us about his art, from its origins to his future projects.

GL. Let’s start with what you consider your starting point, shall we?

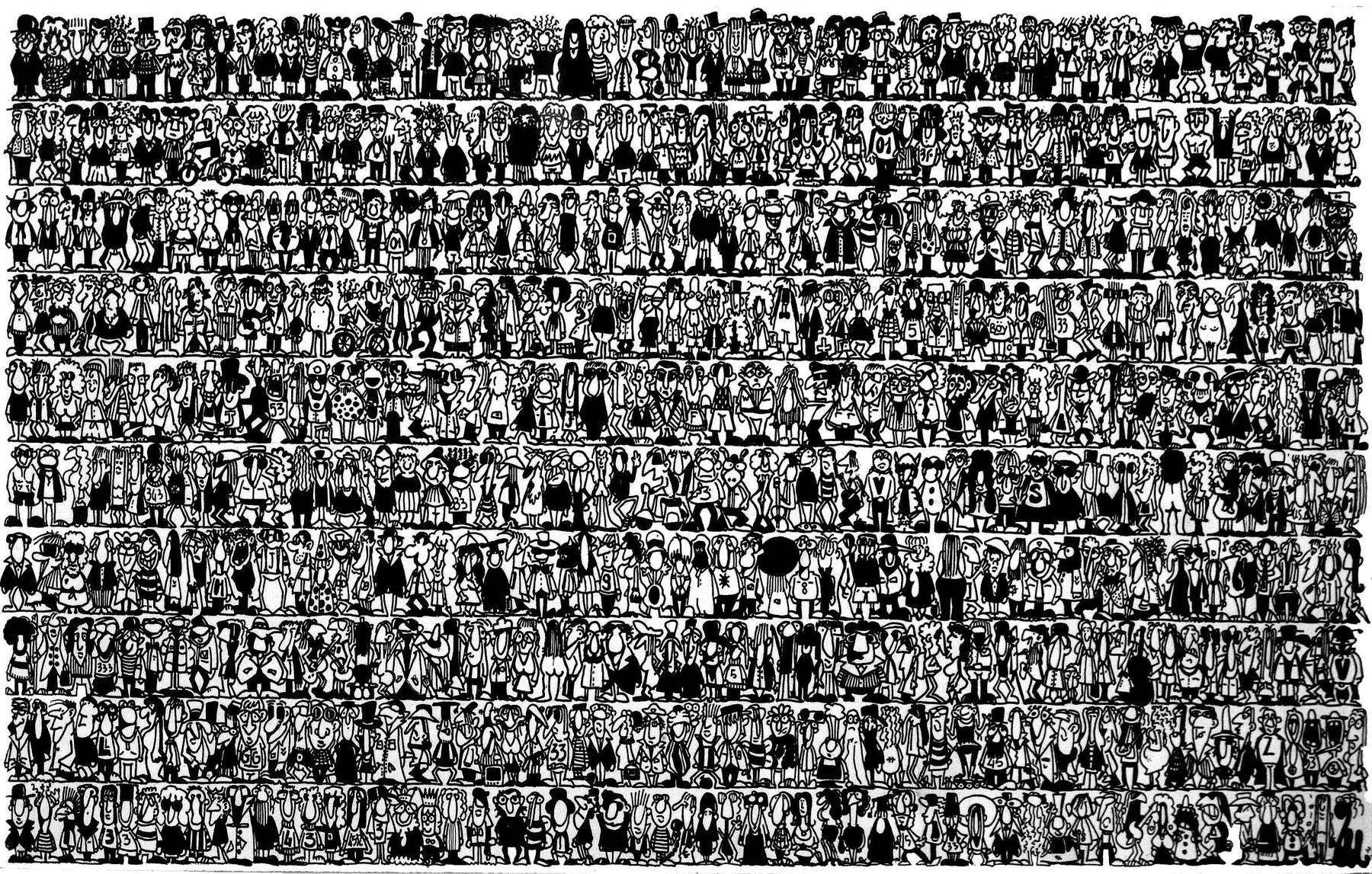

FG. It was 1988 and I was attending the Art Institute in Guidizzolo in the province of Mantua. During classes I got into the habit of drawing for myself. I used to draw little men in rows completely filling small sheets of paper. I often did this during descriptive geometry hours because that subject bored me to death. It happened that one day the professor noticed that I was not listening to his lecture. So he approached my desk menacingly. I feared who knows what reaction. Instead he looked at what I was doing and surprising the whole class said, “Gilberti, go ahead!” As soon as I finished it he asked to borrow it and asked if he could make photocopies that he distributed to the other professors, making "famous that drawing made of 562 little men all different from each other, 2.5 cm high and arranged in ten rows. It was titled The Nun."

First public presentation?

In a way, yes. There is no doubt that the reaction of that professor displaced me and at the same time raised my self-esteem. It encouraged me to continue on that path; I realized that maybe I could do that in life: draw. In fact, I haven’t stopped since.

We met during the Academy in Milan, and there this modus operandi of yours had already developed. Development in the sense that the men were already quite similar to what you do now.

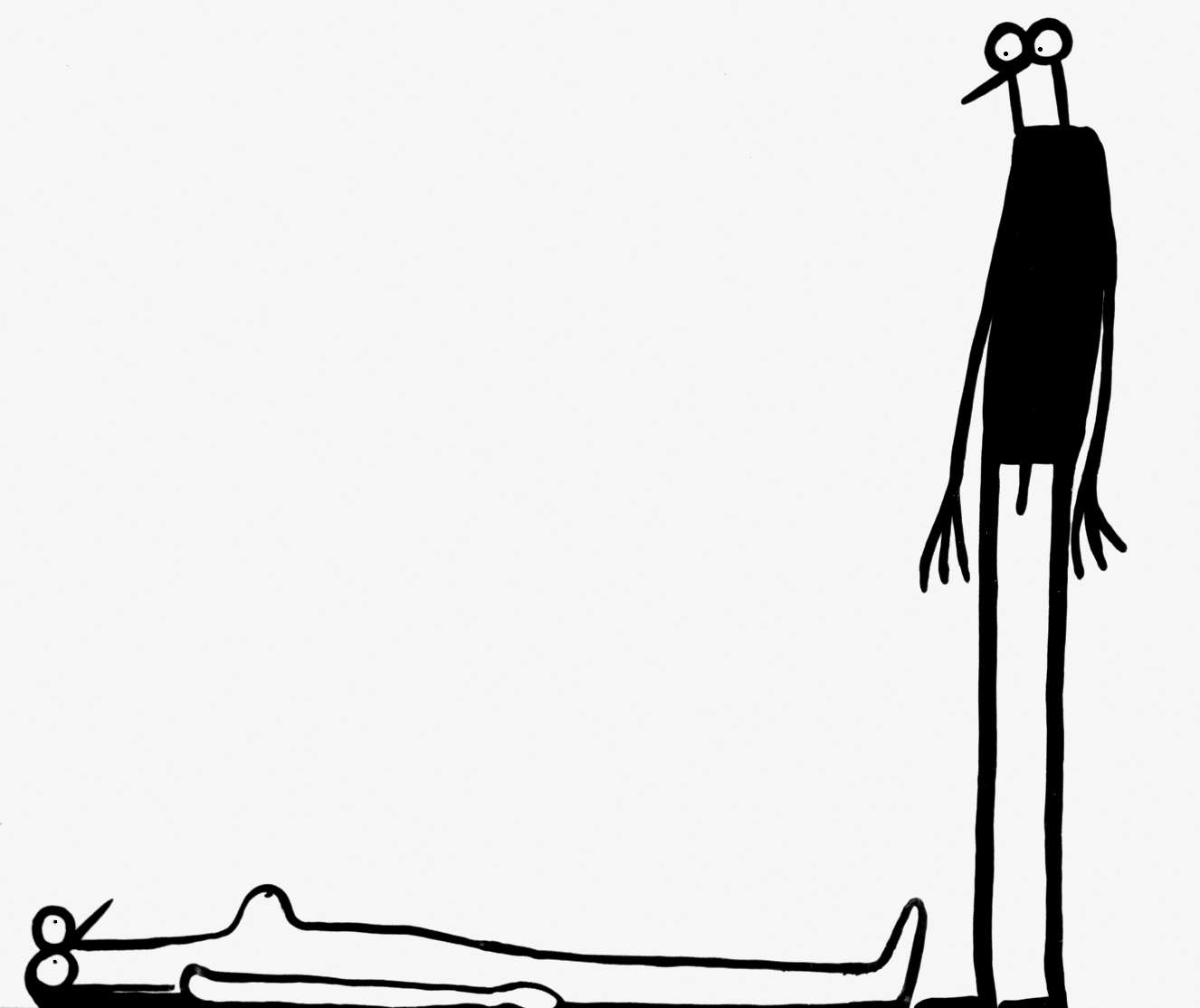

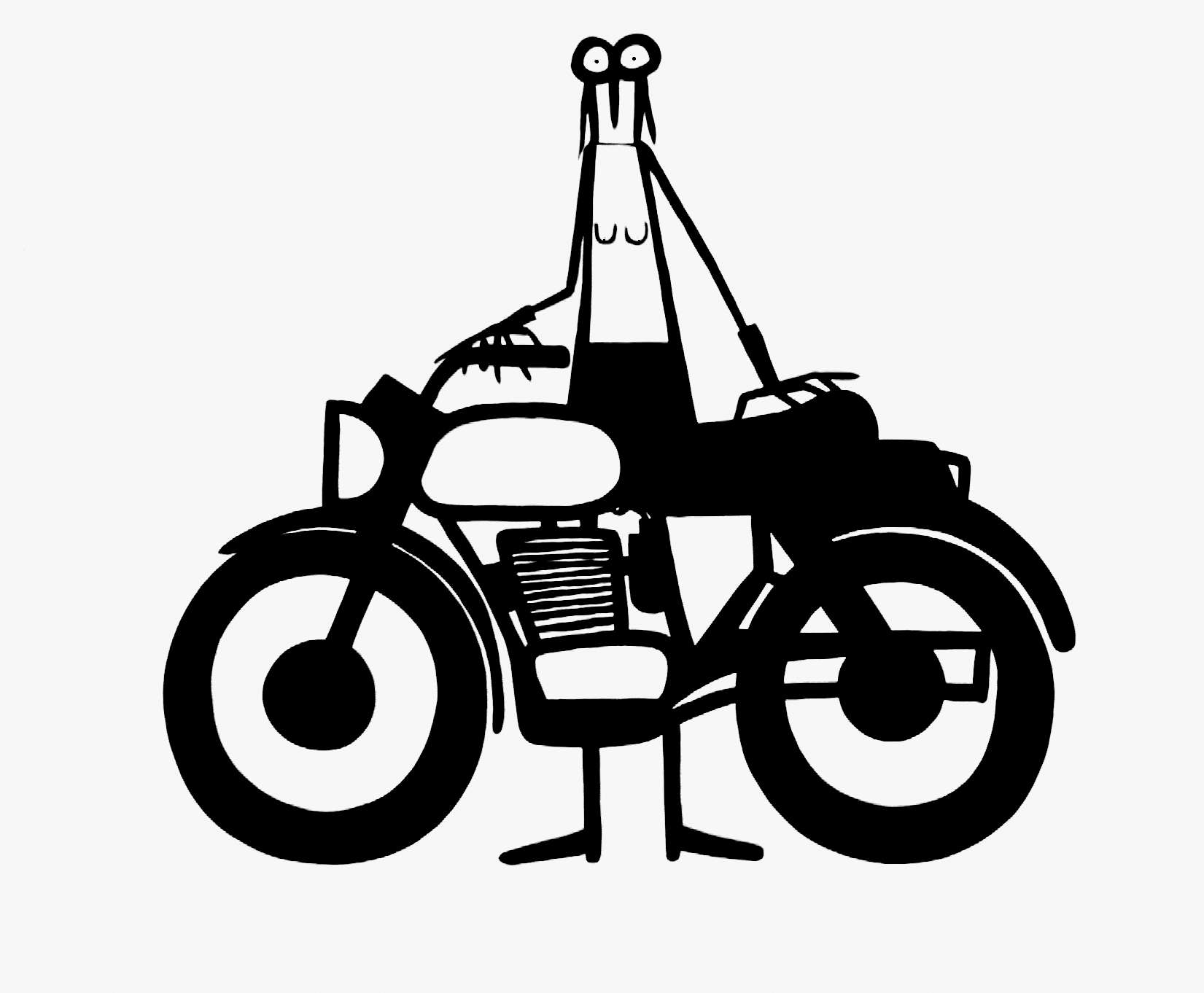

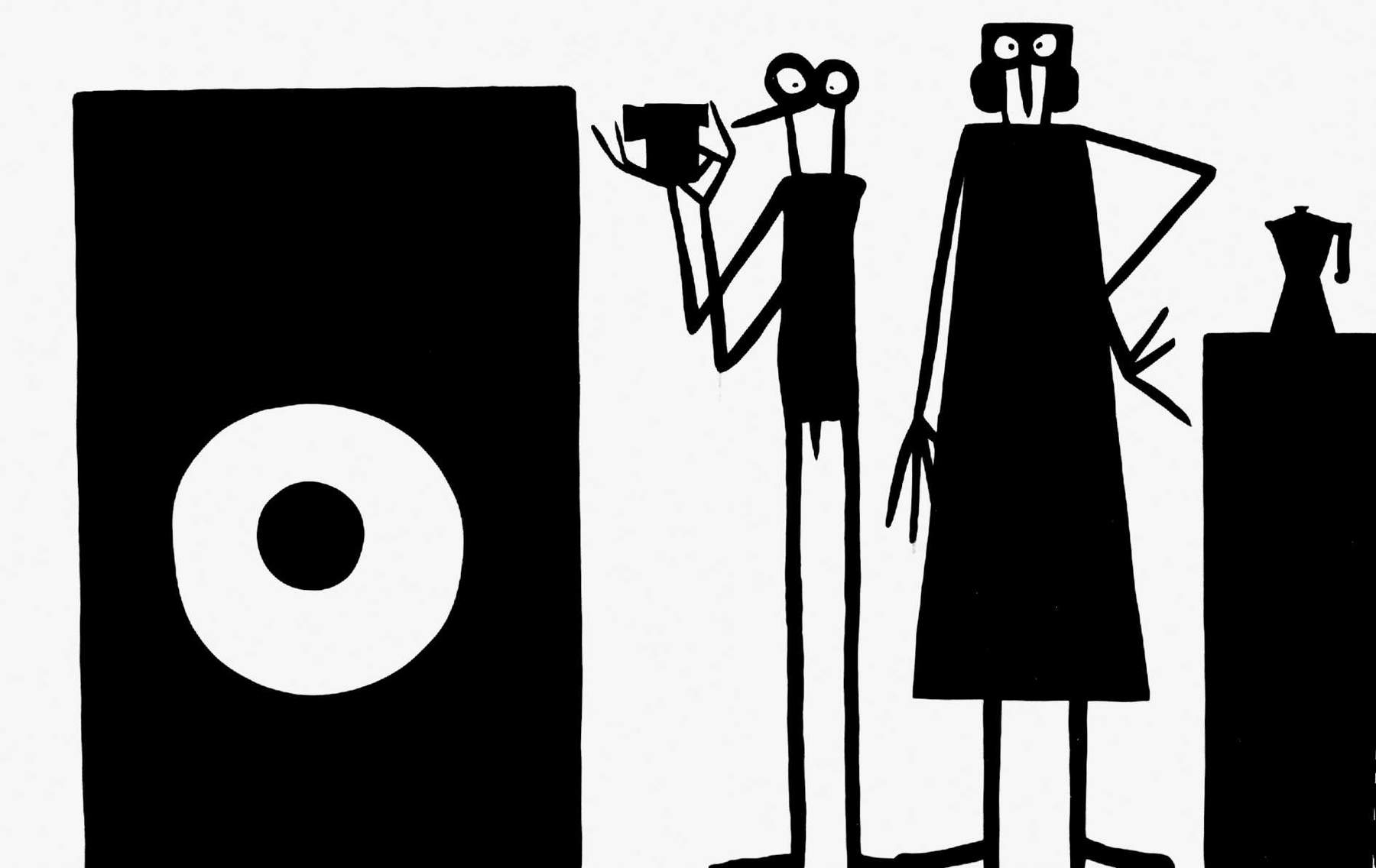

I’ve always been interested in drawing the human figure. In the early 1980s I used to draw characters: human figurines one different from the other. Then when I began to study and learn about art history, especially contemporary art, but also ancient art, I began to evolve my style and merge different graphic styles. I started in those years to do a work of minimizing my mark making. My characters all different from each other became a unique universal little man, always the same. Kind of like Keith Haring’s archetypal figures or Giacometti’s or those in prehistoric graffiti.

So, you basically did a synthesis operation?

A process of sign reduction and synthesis. Even the medieval painting that I like so much pointed me in the direction of synthesis. Especially in terms of the compositional aspect. In fact I tended (I tend) to draw my figures in static poses; actions rather than doing them are evoked as is the case in medieval altarpieces, where figures are represented motionless frontally in a symbolic key.

Does this also go to create a kind of mystery?

That’s right. A kind of expectation. Something undefined that is about to happen or maybe has already happened.

Sometimes then this mystery is unsettling, especially I remember that in the beginning it was a recurring thought of yours to do something that would also arouse some disturbance in the viewer, right?

At a certain point I decided to abandon color and use only black, and I began to silhouette my figures against a white or black background, as needed. I was attracted to certain artists who worked on dark and somber themes. Not just painters and draftsmen. Do you remember when we went to Barcelona together and I found that book by David Lynch in which his paintings were published? Well, it was a kind of electrocution.

Yes, I remember it well: at the bookshop of La Caixa Foundation.

David Lynch already interested me as a filmmaker and I loved his filmic imagery. I also did a solo exhibition at Perugi’s in Padua of oils on canvas inspired by the images and atmosphere of his television series Twin Peaks. My little men were dropped into settings in which there was an eerie and mysterious atmosphere.

Earlier you were just mentioning art history, and I remember that during your Academy years your subjects often came from there, in the sense that sometimes it was the artists themselves and their image that became the subject of your work. I remember by the way a series of drawings you did entitled My Audience.

That series of drawings was my homage toward the work of a particular artist. They became an artist’s book that is now part of the Consolandi collection. In those years, between the mid-1990s and the end of that decade, I was interested in quoting works from the past. I made many paintings revisiting famous works of the past. At that time I had discovered this current of young American painters called Bad Painting. I liked their style, their way of painting very rough and dirty, almost childlike, even though the themes they dealt with were not at all. I got inspired and started painting by literally losing control, in an ungainly and “bad” way. I was letting the color drip down without worrying too much about it. And with this technique that we can call almost expressionist, I revisited works by Rembrandt, by Piero della Francesca, by Giorgione, and several times I painted in a “Bad” key one of my favorite paintings of all time: Van Eyck’s The Arnolfine Spouses.

Ah, these I have never seen!

I had an exhibition of them in Mantua in 1998 by Maurizio Corraini. The exhibition was in fact titled: I am also an expressionist.

I got it-so you were quoting but never becoming a quotationist.

Absolutely far from quotationism as we know it.

I remember in Turin, in an exhibition on drawing, you had done a whole work on Robert Ryman as well. Can you tell about that?

I took a Robert Ryman catalog from which I peeled off all the pages that reproduced his works. Then I took a Rapido pen and filled the images of his blank canvases with tiny little men drawn very precisely and meticulously, as if they were writing. That was also a work that went to pay homage and at the same time to outrage an artist, but in this case, compared to the series of drawings entitled My Audience, the approach was more conceptual.

Yes, indeed it was. This book taken apart on the wall, each page framed, and then these little faces, which when you saw them like this looked like part of Ryman’s work.

I had drawn them in such a meticulous and precise way that the result was as if those reproductions of Ryman’s work really contained those extraneous marks. Up close you could not see my manual intervention. Those who looked at them at first did not understand that under that grid of smiley faces was a reproduction of a Ryman painting.

After these early Turin episodes on the theme of “the public,” followed by the exhibition Siamo fritti, your work takes a more narrative turn. You always remain very evocative, trying to be essential and mysterious at the same time though.

My current work was roughly generated with the exhibition entitled Laura Palmer paintings inspired as I said before by David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, which I did in Padua at Perugi Gallery in 1999. With that exhibition my interest in narrative became more explicit. From that moment I began to draw and paint stories made from a single frame: the space of the sheet or canvas.

I remember the exhibitions and works you presented at Perugi’s in the first decade of the twenty-first century, where each exhibition was always centered on a theme.

In those years, for all my solo shows, I always worked on a theme, making paintings, drawings, installations of modified objects, wall paintings and even a video-animation that dialogued with each other.

At that time you also became interested in Internet pornography, in the sense that you started drawing images taken from that world.

I did a series of paintings that mocked sex and then published a book called Mister Dildo that came out in 2004 for a small publishing house. It collected a roundup of drawings that told in an ironic and sarcastic way about pornography on the Internet. The thing, in those years, had not yet debuted as it does today. There were not many sites and they were somewhat hidden. The inspiration for this book came from the banners that sometimes appeared to me while I was surfing on sites that had nothing to do with the hard world. These ads were always written in English, but often in English full of spelling mistakes, and the texts advertising these sites were quite bizarre. I began to copy-paste the most absurd texts I encountered: I would print them out on drawing sheets and then on them I would make a drawing that dialogued ironically with these hard messages. I titled them Porn Drawings. The introduction to that book, which consisted of three unpublished “porn” poems, was given to me by Tiziano Scarpa.

You then also did some paintings after this book, some canvases. I remember the perverted pedophile, the inflated doll....

In the wake of those Porn Drawings I also painted some big canvases that were naughty and ironic. Here the “bad panting” was coming back, both technically and in content this time.

Then, at some point the taste changes, in the sense that other interests come along, right? There is for example the one for music....

Well, in my works I always put my passions, my interests, my experiences. Basically my life. I think all artists, basically, do that. They tell about themselves. The interest in music I have always had. And it’s faked on paper at a particular time. That is, when my children were born. I became a dad of two small children, Emma and Martino, in the span of 15 months. My time and space for work drastically shrank. I worked mostly at home, and hardly ever went to the studio. I started making small drawings on the kitchen table. Thus was born the series on rock stars. I made about 700 drawings with which I participated in some music-themed exhibitions, and later, a selection of those drawings I turned into a book that I published with Corraini. In Rockstars I told through my drawings the history of rock by writing some pages in which I described my relationship with music over the years, my encounters, my listening and my musical adventures. This book marked a crucial step in my artistic activity: I started working not only for the art world but also, and especially for the world of children’s publishing..

One of the first children’s books you did after Rockstars was Bianca, which in some ways has a lot to do with your young children: is it a book born perhaps for them?

Bianca, along with TheOgre Who Ate Children, are both books I wrote and drew for Emma and Martin. I designed the story for them, but not only that: it was also suggested to me by what was happening around me.

Does this story of the ogre as well as Bianca also have a pedagogical intent? And how did you approach the illustration?

I actually wrote them trying to have fun and to entertain my children and those who would then buy and read them. The interesting thing that happened in making these books is that I jumped right into the new dimension for me of writing and illustration, out of the blue. Writing the stories and then illustrating them with my own drawings. For the occasion, however, I did not go to change my mark. I didn’t choose to make my drawings more pleasing, I don’t know, adding color, for example, or trying to dress them up with details and particulars. In short, I didn’t change my style the moment I went into illustrating my books, even though I knew that I would meet a different audience than in art, more normal and with a different vision.

Was it a bit of a risk?

In some ways yes, but on balance, at the end of the day, let’s say that the public understood and these books and then all the others to follow were quite successful: they were even translated abroad into many languages.

And then they gave a different reading to your imagery?

True, because the “old little men” lost a little bit of that mysterious and evocative aura they had. Inside the book they appear less creepy in their black-and-white look. It is as if next to the text they come to life and sublimate.

They are no longer scary. They even make people laugh at times.

Yes, that’s true, well, maybe then the idea of telling a story in itself maybe subtracts a little bit from that frontality, that kind of unfiltered immediacy typical of the artwork, which makes the images of paintings always elusive, right? The size of the image also matters. Seeing them small or big or huge makes them perceived in different ways. In some cases I have tried to give even a very slight characterization by adding, for example, certain hair styles to the figures. In this way I make my little men, without losing their essential characteristics and synthesis, can from time to time play different roles depending on the story.

In the case of books about artists, have you given yourself rules?

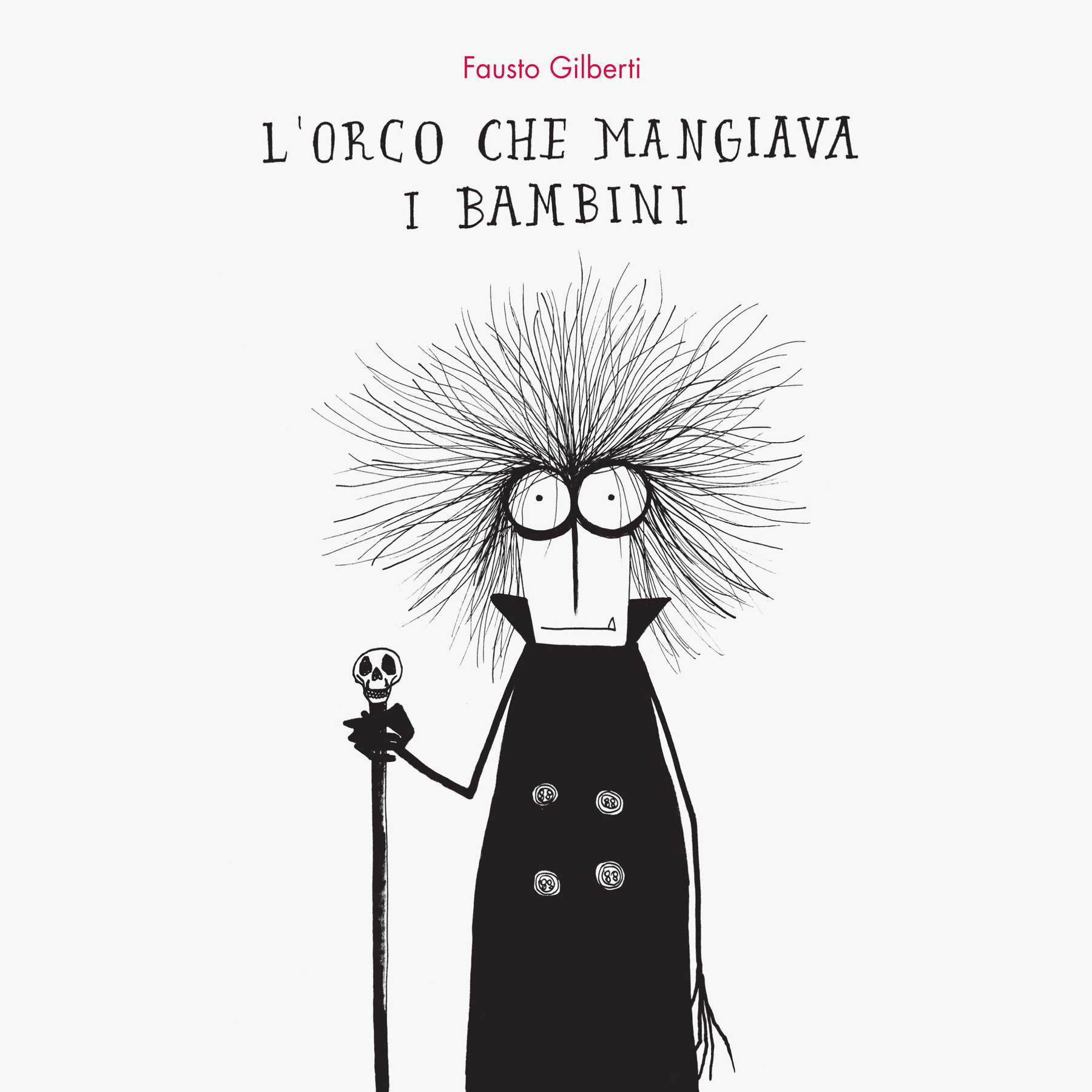

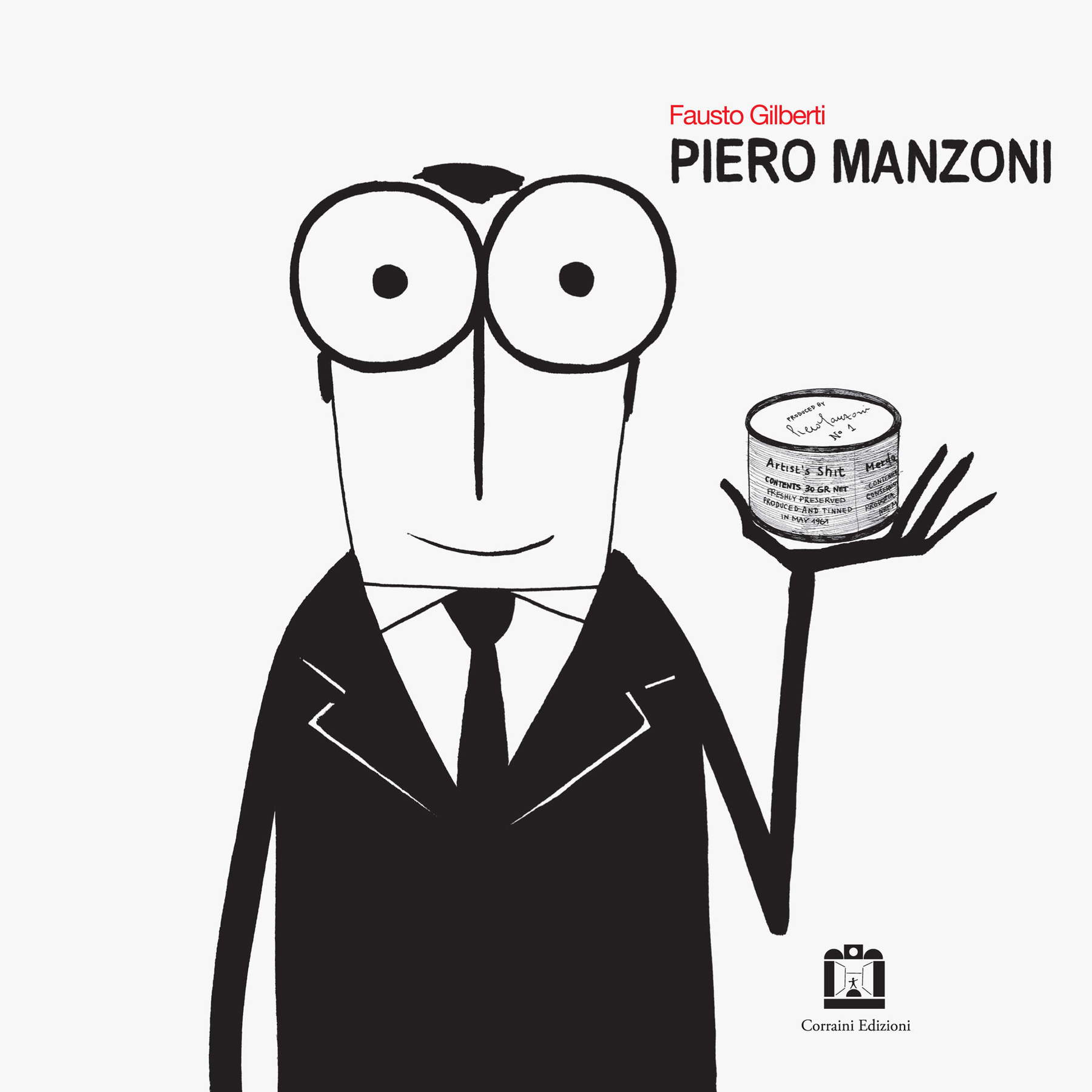

More than rules, I have given myself constraints: never to use photographic reproductions of the works I tell, but to draw them myself, with my own style. Since the first one on Piero Manzoni, I thought that I didn’t want to make didactic art books with ideas for workshops and ideas for activities like there are many around. Instead, I was interested in telling a good story about life and art that was curious and, if possible, even entertaining. Even at the cost of leaving out important biographical aspects, but which I considered boring or too technical and not useful to the lightness with which I wanted to tell that story. Seeing what the publishing world was offering, I also realized that it could be a new avenue. Finally, I chose to tell artists that no one had ever told children. The most revolutionary ones. The most conceptual. The ones that make adults turn up their noses. The ones who are often looked at with prejudice. Like Piero Manzoni, Yves Klein, Lucio Fontana, Marina Abramovic, Marcel Duchamp.... .

With some of the artists you’ve worked on there have also been some problems with permissions: more with their heirs than with them, since they are no longer in this world.

This series of dedicated books has 9 titles to date. In reality, however, I have narrated 11 of artists. Two of these books, unfortunately, although ready for publication, I have not yet been able to materialize them because of permissions and rights problems: Basquiat and Haring.

Then, these real-life characters that you have told about in the books along with others, have they also become protagonists of some very large paintings?

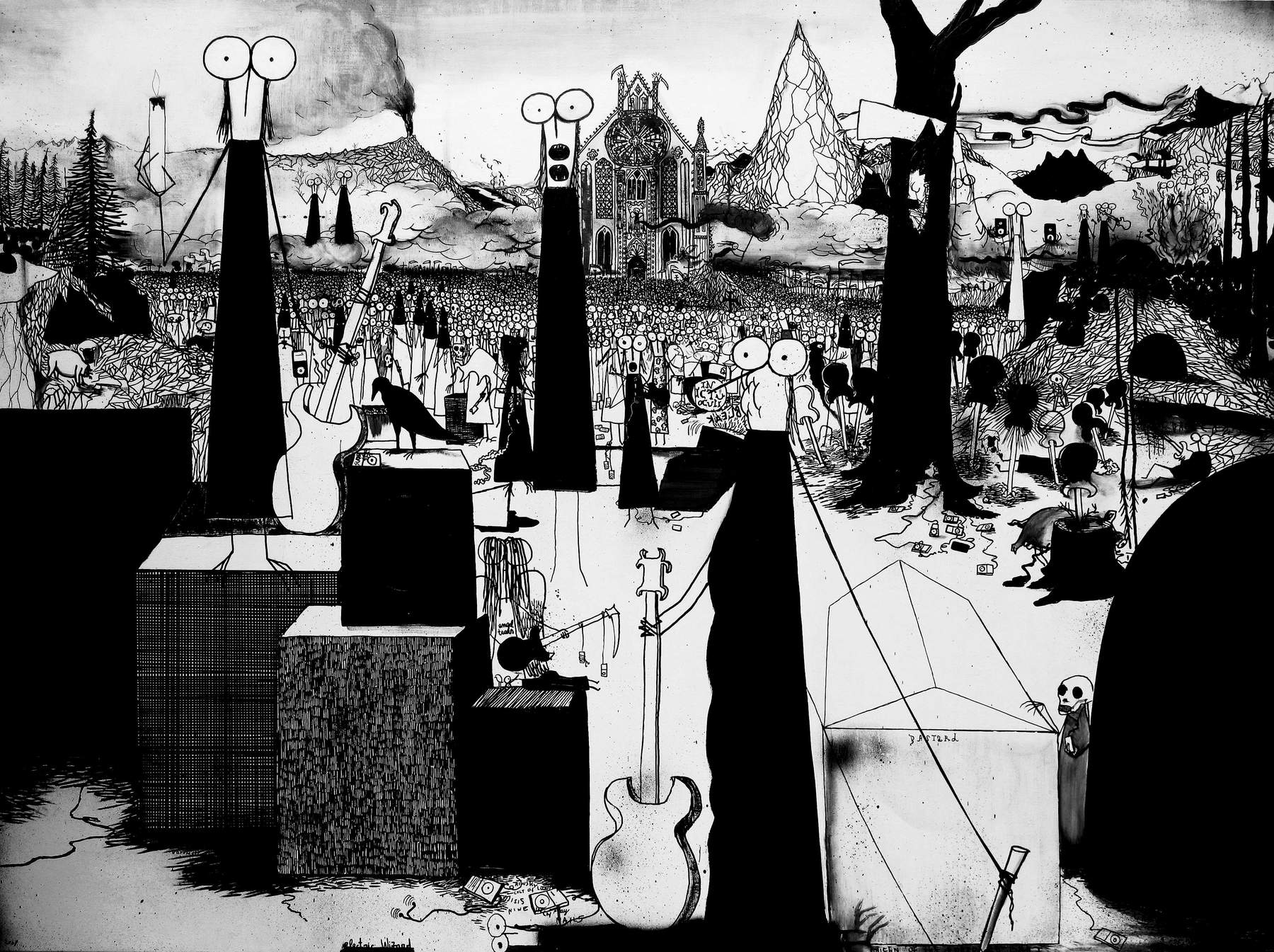

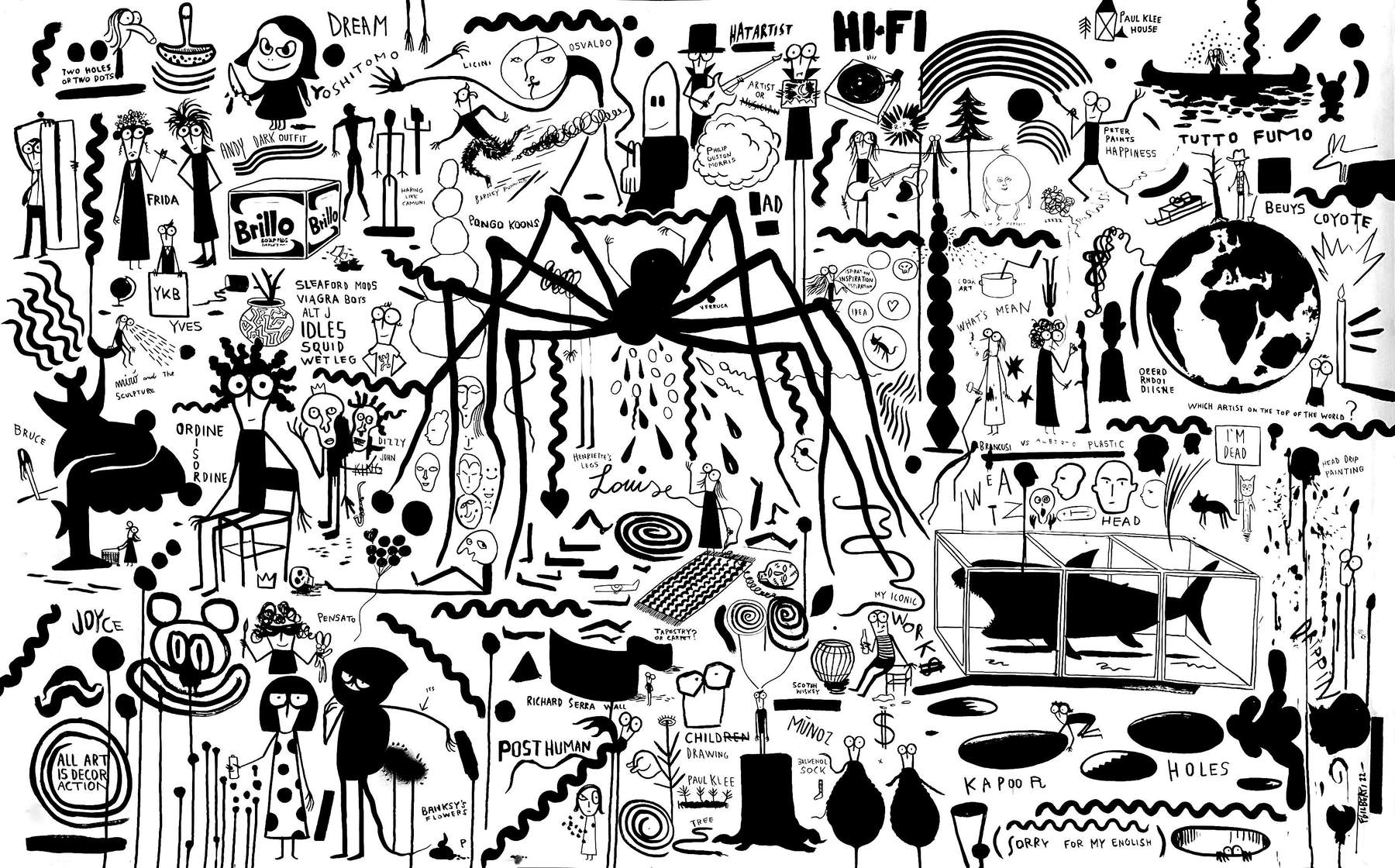

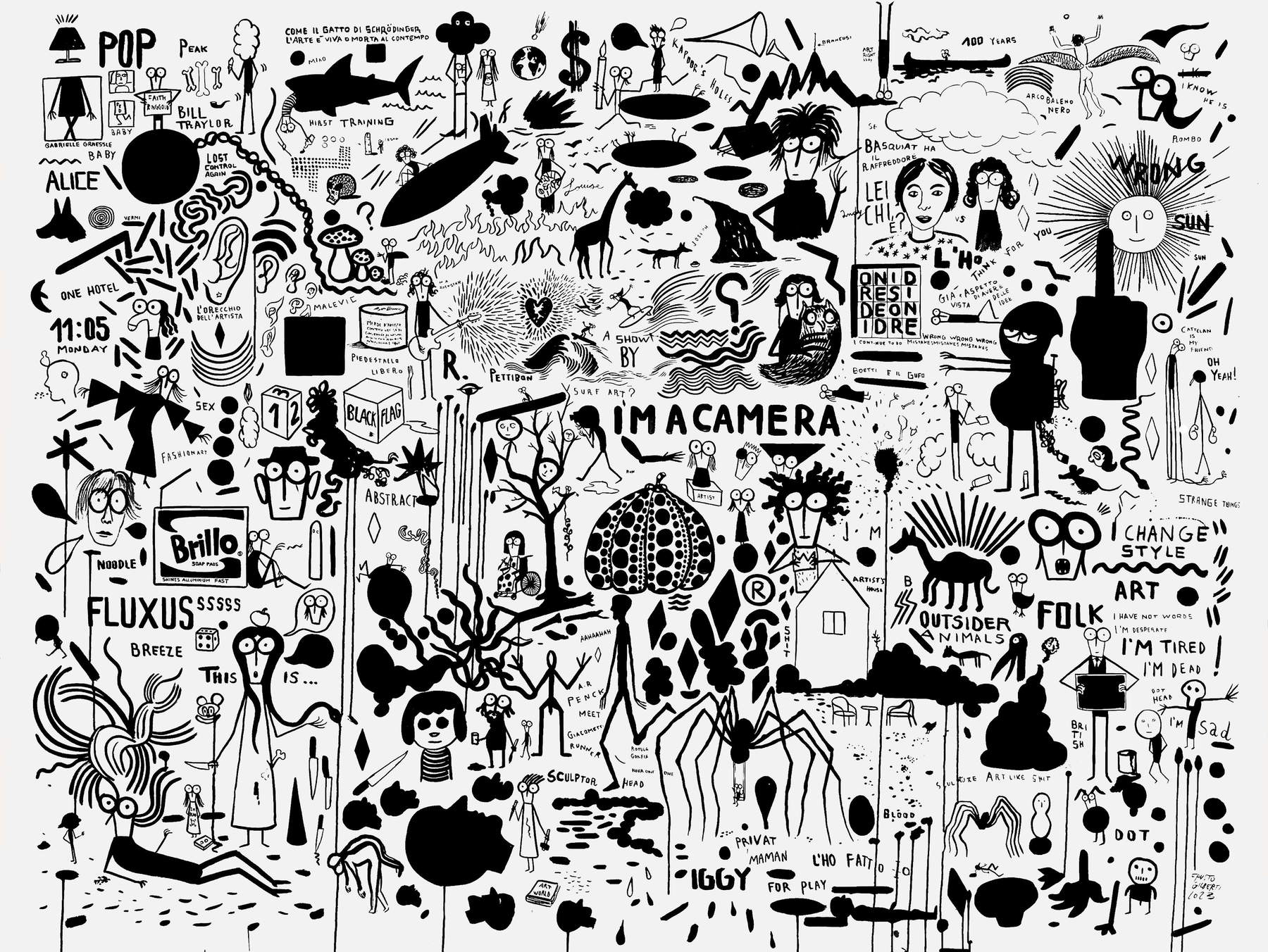

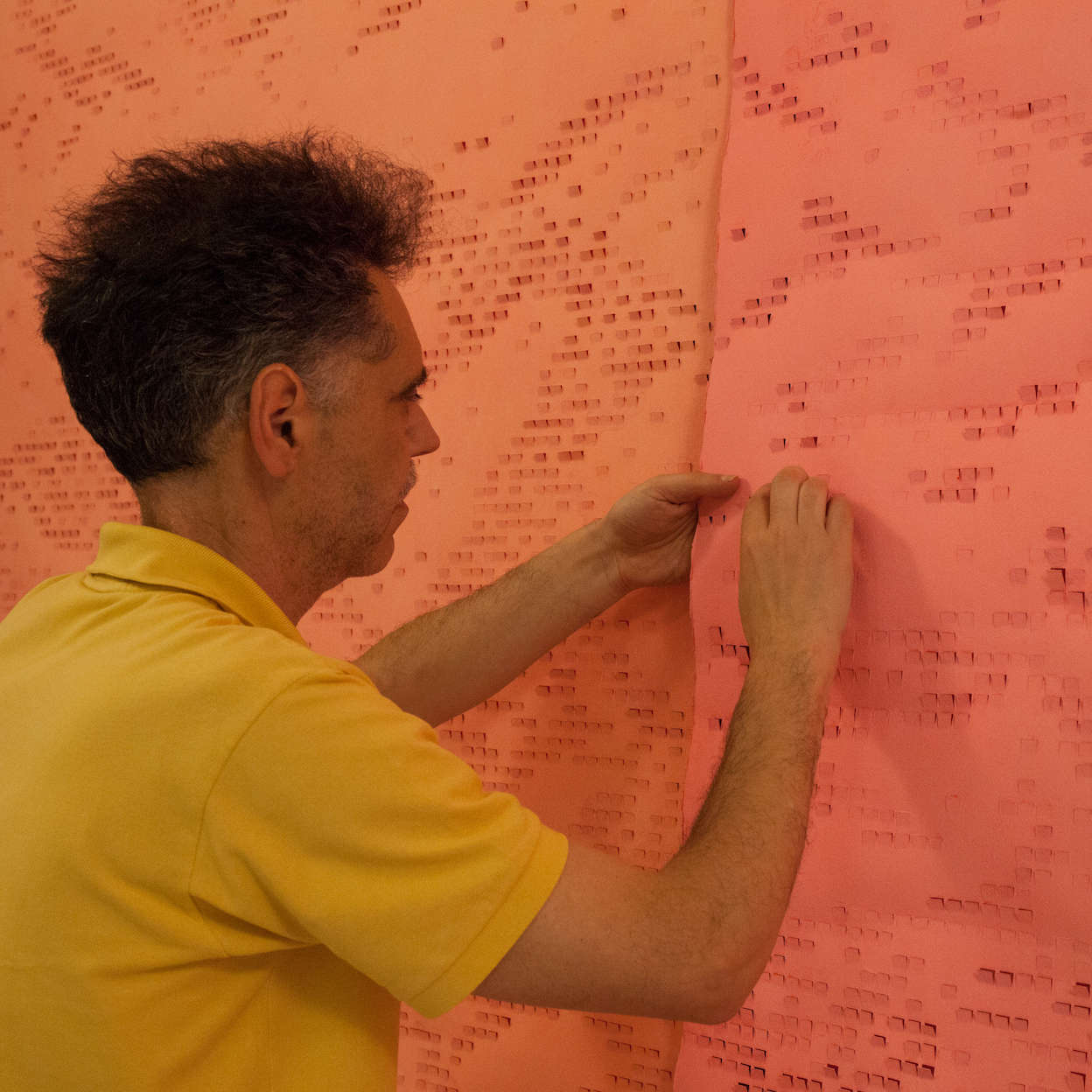

I have done in recent years, alongside the books, a large series of large drawings dedicated to the theme of contemporary art. I started filling large papers with scenes taken from the world to contemporary art. This series of large papers I titled Artstars.

I mean it’s a bit of an account of all those things that somehow in that area interest you, an ongoing reflection.

These are drawings where I throw in all the art that I like, that I know, that I’ve seen live, that I remember, that I see in books and art catalogs that I have in my studio. Again, these are experiences, passions, images that are part of my cultural background, which are transformed into graphic composition. I work by drawing one scene after another until the paper is literally full. A kind of horror vacui. Sometimes while I’m working I’m reminded of Pollock, who would drop a drop or let the color run and then proceed without letting chance take over. He controlled his gesture to the end, even though at first glance his paintings might seem competitively completely random. I, too, when working on these large drawings throw out the first “drop” by making the first drawing in one part of the sheet, then I proceed by moving around the space adding more images until I create a breathless competitive full, in which everything, however, is in harmony, in balance between solids and voids, whites and blacks.

Well, there is something, pass me the term, Japanese in that -- in the sense of striving for balance. These new works, which you just exhibited in Modena, however, how do you make them? Do you already establish the size or do you start off and then at some point say, “All right, this ends here...” and then cut the canvas or the paper?

I always establish the size before I start. I prepare the sheet, attach it to the studio wall, and then draw without making a preliminary plan, however. Always, for me, the drawing is already finished work. In the sense that I never use pencil to sketch the work. I have always drawn and painted on the spur of the moment without preparation.

In doing so, it often happens that I make mistakes that seem unrecoverable.

Actually over the years I have realized that mistakes can suggest new paths to you. You have to seize this opportunity. Have the path suggested to you. Follow the error to find new and unexpected solutions.

If art was just design and execution it would be boring as hell, don’t you think?

There are artists who go in search of meaning and disregard everything else. Form, sign, composition, subject...

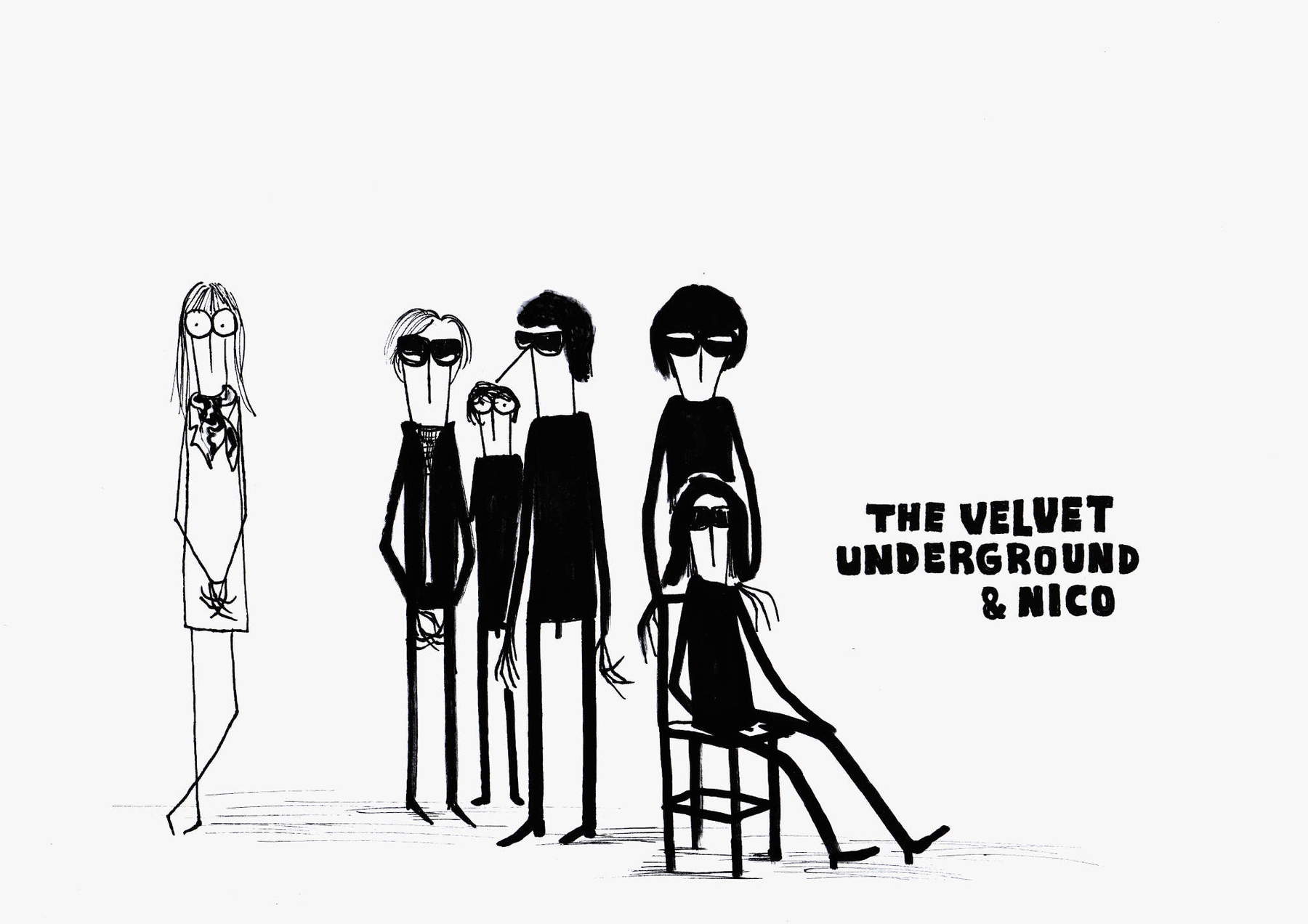

Look, in addition to these very large works you have done in recent months a whole series of very small drawings in which instead that very situation returns, let’s say, more mysterious, more disturbing. More narrative.

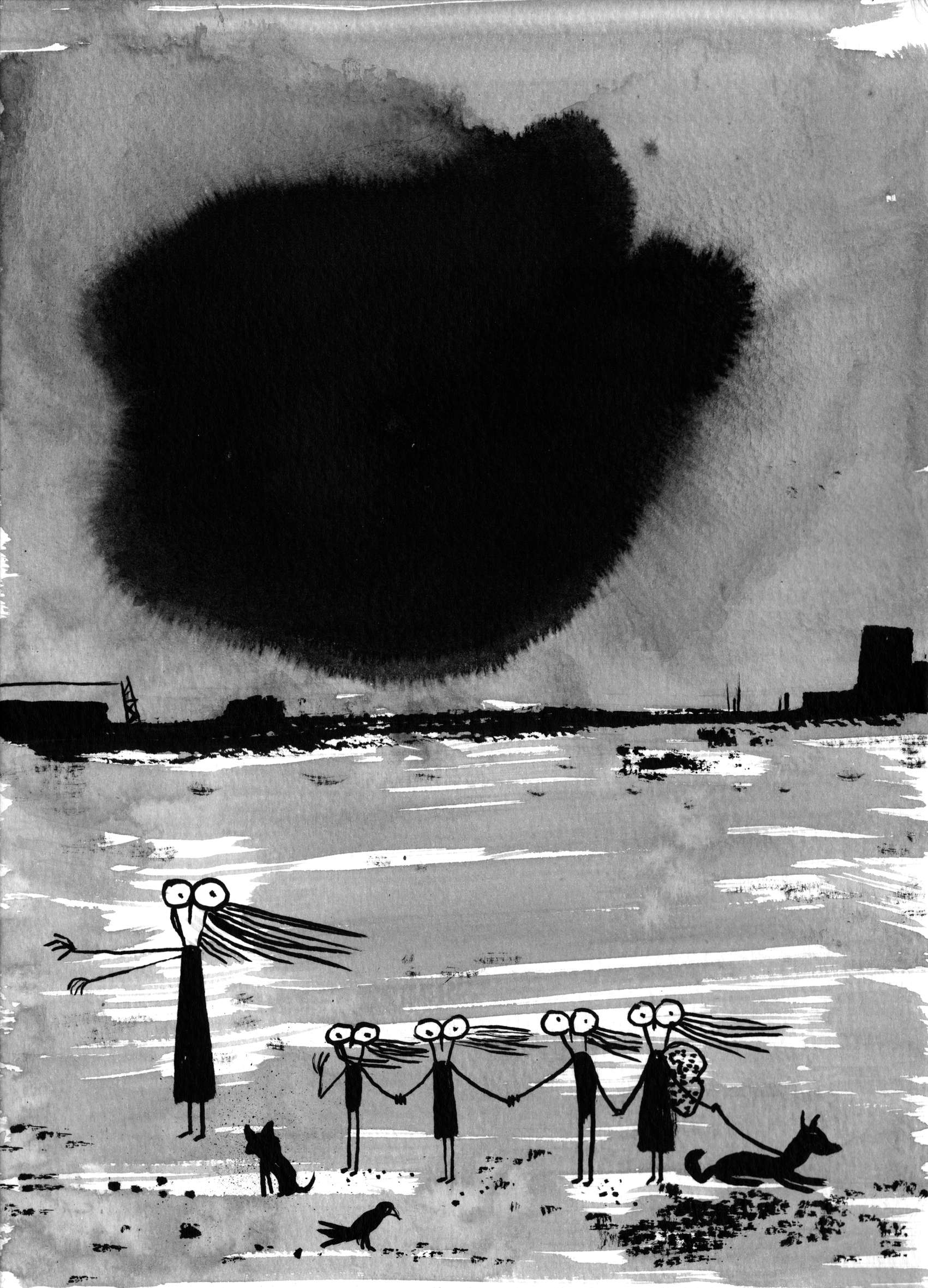

You’re referring to the Fright Drawings series in which certain atmospheres from the past return. They are breathless images, visions in which dream and reality often interpenetrate. With everything in them that interests me: music, art, quotes, mountains, landscape, cinema, literature.

And then there are situations that arise from what you have around you, from the situation in which you are exhibiting for example, when you did the Happy mountain exhibition two years ago if, I remember correctly.

You also get inspired by what you have around you. Sometimes even by the landscape and the places. In that case, helped by a dozen or so super assistants I painted on walls of an abandoned former summer vacation colony in Ollomont in the Aosta Valley

Let’s go back to the small-format drawings you’ve done recently. The Scary Drawings.

They are formally different drawings than what I have done so far. I have been working on new subjects but also on finding a technique. I started to dilute the India ink, to not just use pure ink anymore. Not just black, but that many shades of gray, glazes and overlays. I tried to draw by deliberately losing control: I purposely caused the mistake. I used damaged brushes and used them in various ways. Folding them, using their sides, the edges, in search of a particular and very expressive, painterly mark. Also, in the background and around the human and animal figures, the landscape appeared, often dark and made of chaotic and swirling, stormy shapes, almost never quiet.

Now let’s go back and forth in time, shall we? I have a series of books that have used some of your drawings for the cover that are about the stories of Lunigiana. For example, what struck you about these local stories. Many of them have somber, dark, mysterious, almost mournful tones....

I was in Lunigiana a few years ago for an artist residency during which I created an artist’s book inspired by the stories of Lunigiana. I had read them in a small volume written by a local scholar, who had collected them over the years by having them mostly told by local elders. They were almost always scary stories, and they struck me because the characters who populated them were really unusual and bizarre. Death was often present, and it was told with a note of irony, perhaps to exorcise it. I remember that in one of those stories there was a story about a guy who one night going through a forest (Lunigiana is full of forests) saw in a small clearing some people dancing and having a good time. So he started dancing with a woman. He was happy and content until he realized that the person he was dancing with was dead, and so were all the others around. I made a series of signs inspired by those stories and made a book out of them in the leporello format.

Then I remember when we were at the Academy you had brought for an exam with Roberto Sanesi, a series of drawings, where there were landscapes, basically, very painted drawings.

They were plates inspired by Dino Buzzati’s Desert of the Tartars. They were small acrylic paintings on paper. Uninhabited landscapes, black, with only the presence of the fortress in the distance. Man was absent. They were almost informal, almost abstract paintings. The forms were resolved with brush strokes, with a mark.

Finally, Fausto: What are you working on at the moment?

I am continuing my research on Drawings from Fear , trying to get the same freshness of sign that I found in the small size on much larger sizes instead. A kind of Disegni da Pa ura part 2. A hundred of these papers will be collected in a publication coming out soon from Corraini edizioni. A book rather than a catalog, with a very short introduction written by my writer friend Sacha Naspini, author of magnificent novels with dark and fascinating settings very much in tune with my poetics. If you are not familiar with him, I recommend you read “The Cariolants.” The book will feature non-stop pagination: drawings will be published on the page live and one next to the other, with no interruption of blank pages and no additional titles or information. Conceptually it graphically echoes the installation I made of it at the Wizard gallery in Milan in last year’s exhibition.

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.