Established in 1982, the Museo Civico del Marmo is the first public museum to arise in Carrara. Conceived and created by the writer on behalf of the Municipality of Carrara (G.C. Resolution No. 582, 8.4.1982), it was set up as a “progressive” structure, largely aimed at “material culture,” created for the purpose of collecting, studying and protecting materials related to marble culture. Its establishment had been preceded by five years of research in the area directed toward the documentation and collection of studies and historical-archaeological material evidence on the history and significant characteristics of Carrara’s marble activities, from Roman times to the present day. Of particular importance has been the research and surveys carried out in situ on the Roman quarries of Carrara and the types of marble extracted there, activities never previously carried out except at the level of publications and in a very partial way.

A museum, therefore, born out of the need to protect materials fundamental to the history of Carrara and beyond, and conceived as a public service for the collection, protection, study and enhancement of materials pertaining to the history of Carrara marble. The structure and museum activities were regulated by special statute. The venue was located in the prestigious pavilions of the former National Marble Exhibition, an important initiative realized in the 1960s by the Massa Carrara Chamber of Commerce but destined to close after a few years for reasons that were never really clarified. This was made possible through collaboration with IMM (president Giulio Conti), which then had the availability of the premises, and an agreement with the aforementioned Chamber of Commerce.

The inauguration of the museum coincided with the creation of the "Lunense Marble Exhibition" (1982), a first exhibition that documented the results of the research carried out, which was followed over time by important acquisitions (the result of purchases and donations) related to materials of Industrial Archaeology, the former Sculpture Biennials, archaeological and artistic marmology, the important Marmoteca, craft artifacts and documentary materials. Thanks to Mayor Marchetti’s important ordinance (3.2.1989), which is still in effect, the artifacts that came to light in the quarries have been subjected to control by theMarble Office and to protection, as required by current laws, with accommodation at the Marble Museum by the Culture Sector.

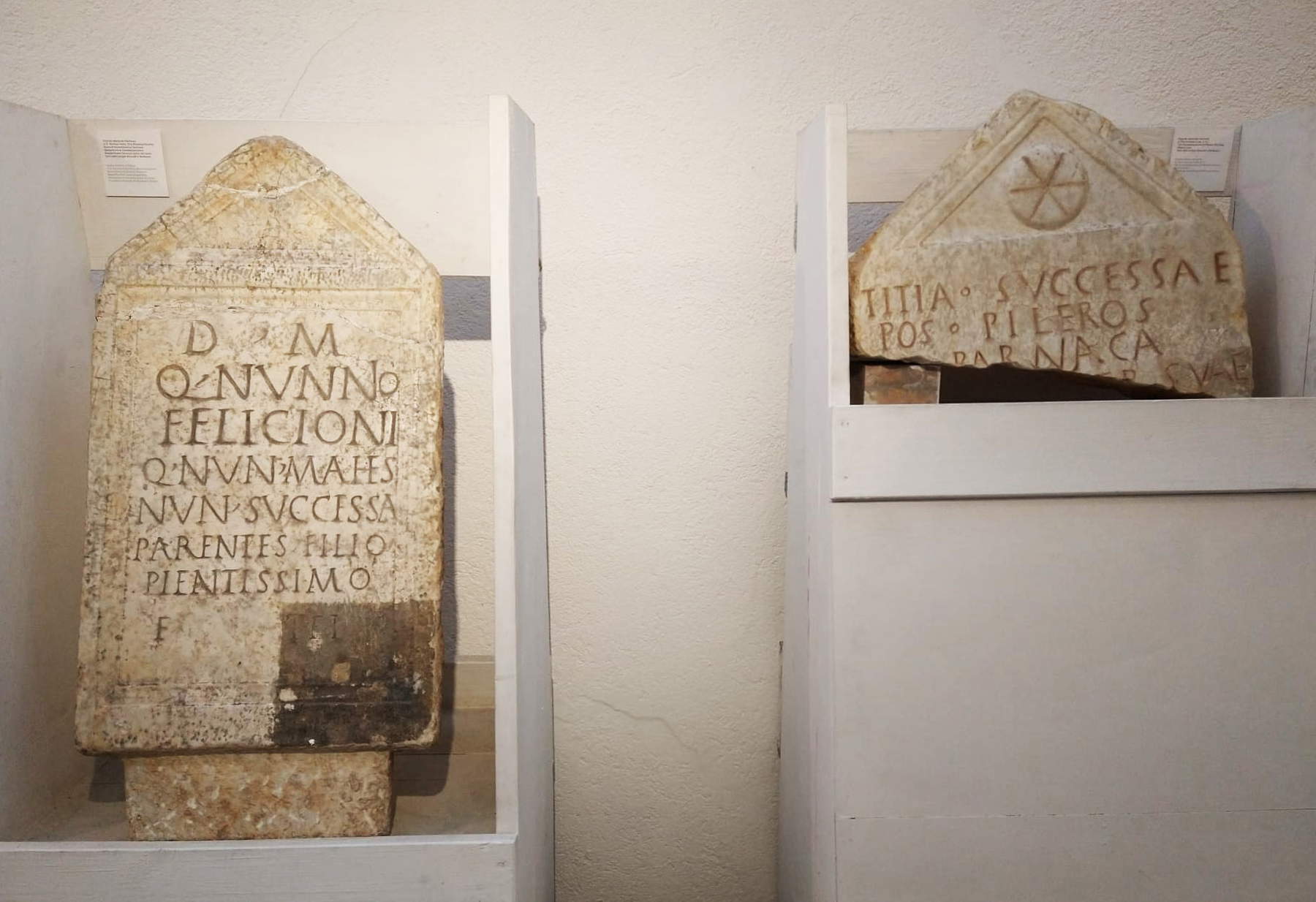

The recovery of semi-finished products from the Roman period (many of which have nota lapicidinarum) has continued over time. As far as the archaeological collection is concerned, in 2006 (the year of the publication of the museum’s catalog-guide) at the museum there were: 17 column capitals; 6 column bases; 54 squared and inscribed blocks; 8 anepigraphic squared blocks; and 5 sectors of cut-outs. Recoveries continued until 2009, when deliveries to the museum ceased. The reasons for this inactivity on the part of the municipal offices in charge (Marble and Culture sectors) are unknown.

Subsequently, three exhibition sections dedicated to the artistic craftsmanship of marble were moved from the museum’s halls into storage in order to provide space for some contemporary art exhibitions organized by former culture councillor Federica Forti, who at the time collaborated with then culture councillor Giovanna Bernardini. The three sections still lie in a municipal warehouse, forgotten by those whose institutional duty it would be to take care of them. After 2009, the semi-finished products of archaeological interest that continue to come to light in the active quarries remain at the quarries themselves with serious prejudice to their integrity and preservation in situ. This is a situation that blatantly contravenes the provisions of municipal regulations and state laws regarding the protection of the national archaeological heritage.

Currently, the museum (for which no scientific director has been appointed) is managed, as far as only maintenance and enjoyment is concerned, by the NAUSICAA company. On the part of former culture councillor Federica Forti, the desire to partially transfer the materials to the 17th-century Palazzo Pisani in Carrara has been announced several times: however, it would mean dismembering the museum structure. A major architectural firm has been entrusted with the project of renovating the said palace.

The lack of a stable scientific director over the years has undoubtedly fostered discontinuity in museum activities, especially in terms of increasing the materials within the museum’s purview and adjusting the structure. The directorate, in practice, has been managed by the culture department only as day-to-day administration. However, it remains an inexplicable and extremely serious fact that the recovery and protection of artifacts of archaeological interest that incredibly continue to come to light even today in Carrara has been interrupted.

These are materials of national interest that only Carrara can boast in Italy and are subject to state and regional laws on cultural heritage. The past municipal administration, as the first act of its cultural policy, planned a “new marble museum,” in a historic palace in the center of Carrara that, due to its structure and historical-architectural characteristics, will not be refurbishable and adaptable to the exhibition and fruition needs typical of a museum. In practice, on Palazzo Pisani, according to the relevant laws, only conservative restoration work can be carried out.

Moreover, on the museological level, dividing the Marble Museum into two locations three kilometers apart is something that makes no sense on the cultural and fruitive level. The thing is so illogical that one would think that the real intentions of the past municipal administration were quite different in spite of Councillor Forti’s latest statements on the subject, regarding the fact that the “Museum of the City of Marble” should be created in Palazzo Pisani and not a “new” Marble Museum as had been previously announced. Word games that did not portend anything good.

Rediscovered, archaeologically surveyed and studied in its components by the writer in the years 1977-80 on behalf of the Municipality of Carrara, Fossacava, the most important original Roman quarry in the Apuan and Italian area, was published in the volume Carrara Cave Antiche (1980) dedicated to the first archaeological survey of Carrara’s ancient quarries ever carried out. This volume, known and appreciated internationally for the novelty of the subject and for the scientific rigor applied to a field as unusual as it is difficult, turns out to have been completely ignored by those who were commissioned by the Municipality of Carrara to provide for the design of the project and the didactic system recently created on the Fossacava site, but also by those who had dealt with it back in 2015. In the illustrative signs, as a predecessor to the operations carried out since 2015, Luisa Banti (inspector of the Archaeological Superintendence of Tuscany) is cited, who, however, in 1931 had published a simple list of archaeologically interesting Carrara sites, devoting only five entries to Fossacava and writing very generically that the site “has numerous Roman cuts.”

In Carrara Cave Antiche, pp. 64-95 are devoted to Fossacava, in which 63 entries appear dedicated to individual archaeological evidence related to the cut traces and, on pp. 104-106, the plan of the complete site and the complete graphic survey of the documented traces. Precisely from the wealth of evidence provided by Fossacava, it was possible for the writer to understand in its completeness the excavation techniques employed by the Romans in the marble quarries.

None of this appears in the panels recently placed on the site, equipped with “QR code” and graphically made in the style of “Disneyland,” in which it is stated that "Here in 2015 for the first time in the world the archaeological excavation of a Roman quarry was carried out.“ In reality, the ”excavation," carried out quickly by bulldozer, uncovered only a part of the southern flank of the large quarry (below the wall sectors not covered by the accumulations of flakes and the subject of the 1970s surveys), leading to the recovery of some semi-finished products and pottery fragments but leaving more than two-thirds of the entire original Roman excavation area untouched.

If a complete excavation of Fossacava had taken place, Carrara today could exhibit the original site of the largest Roman marble quarry in Italy and one of the largest in Europe. In addition, additional important finds would probably have come to light and, most importantly, the overall layout of the ’workshop as it was when it was abandoned in the late 3rd century could have been documented.

In 2015 the excavation and related captions (with many errors and now replaced) were carried out by the Archeodata cooperative of San Giuliano Terme under the supervision of the Archaeological Superintendence of Tuscany (Dr. E. Paribeni). In panel 11 the “great Roman cut” is presented. Actually by the term “tagliata” in archaeological marmology we mean only the inner part left in the wall of the “trench” (which could contain more marmorarii at work) excavated with subbia and mallet, descending in depth until meeting one of the natural fracture planes of the bench. After that, wedges were driven into the sidewall towards the outside of the trench itself, which, beaten with mallets, allowed the part of the marble wall towards the quarry forecourt to break away. Therefore, what can be seen today on the southern flank of Fossacava is not “one cut” but a series of cuts, all corresponding to the inner faces of the various excavated trenches, more or less deep and long, which remain as evidence of the excavation technique used.

A reconstructive model of Fossacava made to scale in 1989 can be seen at the Civic Marble Museum, in which the trenches made over time are highlighted and ideally reconstructed, and which, once detached, led to the situation visible today. In the educational panels displayed today at Fossacava, not only is there no reference to these techniques, but neither the Marble Museum nor the model with ideal reconstruction of Fossacava made in 1989 at the direction of the writer and executed by the sculptor Cherif Taoufik (a gift from the Rotary Club of Carrara and Massa) is mentioned. Therefore, it should be assumed that those responsible for the latest arrangement of Fossacava are not even aware of the existence of the Marble Museum and its contents.

In panel 12, reference is made to the exhaustion of the marble “seam” (correct term “marble bench”). In reality, since we have not taken the excavation to the depth of the last ascertainable quarry yard, we do not know its original level and therefore cannot know exactly when the quarry stopped production and whether this was related to the exhaustion of the bench. Panel 14 attributes the end of the quarry’s exploitation to the rise of new fashions on the use of colored marble in the Roman world. Thus one would attribute the introduction of marbles of “colored qualities” into the Roman market at the end of the third century. Now, apart from the fact that the “variegated blue” type of Fossacava, mentioned by Strabo, is itself a “colored quality,” all those involved in archaeological marmology (a relatively recent but well-established specialization in the archaeological field) know that the fashion for theuse of colored marbles of all sorts goes hand in hand with the development of imperial power beginning with Augustus and with the accumulation of wealth of the Roman ruling classes as early as the first century. For that matter, one need only go to Luni and see that many types of fine colored marbles, including imported ones, are already widely used in buildings of the Julio-Claudian age. The third century, on the other hand, constitutes precisely the beginning of the crisis in the use of colored marbles caused by the progressive difficulties recorded in the Roman Empire in various economic and social sectors, especially in its western part. Therefore, panel 14 contains an unbelievable jibe moreover paid for with public money like everything else that has recently been done at the site.

As for the semi-finished artifacts that came to light with the 2015 excavation there is to note that many of them are marked with nota lapicidinarum, that chisel-engraved mark that often gives valuable technical and chronological indications. Very interesting are some notae engraved on some half-finished labra as well.

However, leaving these materials in situ does not guarantee their proper preservation, while the most significant ones (according to special ordinance) should be arranged at the Marble Museum to integrate the very important existing archaeological collection. Integration that should also concern the current museum area dedicated to Fossacava whose documentary materials practically date back to the first years of the museum’s existence.

It is truly embarrassing to comment on the superficiality and errors highlighted here by taking note of the public and private entities that have supported, financed and directed what has been done at Fossacava in recent years. The Municipality of Carrara, and in particular the Department of Culture and the Marble Office (both the Marble Museum and the Fossacava site fall directly under the management responsibilities of the municipality) should make sure of the level of professionalism of those to whom assignments are given, spending public money. Which, evidently, has not happened.

Moreover, one of the most obvious things that jumps out at those who visit Fossacava today is the recently implemented attempt to make it an archaeological facility independent of its natural body of reference, which, by institution, is the Civic Museum of Marble. At Fossacava, ancient tools found over time in Carrara’s ancient quarries (and not at the site) have been arranged, and a virtual film that roughly illustrates the workings of the ancient quarries of Lunigiana can be seen.

In the entire communicative system created at Fossacava, there is not even the slightest mention of the Marble Museum, so tourists visiting the site are not put in a position to learn about the great heritage of materials and knowledge acquired in Carrara on the subject of marble archaeology. The whole thing seems to be part of the project, repeatedly and proudly enunciated by the past municipal administration, geared toward dispersing the Marble Museum and its heritage.

It should also be noted that, on a strictly archaeological level, the approach given to the operations carried out at the site is the work of the suppressed Soprintendenza Archeologica della Toscana, which followed the partial excavation of Fossacava in 2015. Moreover, with regard to the marble finds unearthed, the decision to leave them in situ is a harbinger of the progressive decay of the notae engraved on them while the ceramic fragments, evidently considered more important for the purposes of chronology assessments, were recovered. Fragments that are not present in Carrara today.

How can such short-sighted choices be accepted? As all this was not enough to highlight the incredible situation outlined here, there was also the placement in the Fossacava area of several semi-finished items with nota lapicidinarum not pertinent to the site including one of the most important Latin inscriptions found in Carrara already in a precarious state of preservation which, remaining outdoors at the mercy of the weather, is destined for further deterioration as will happen to all the others.

In 2018 the active quarries with stocks of semi-finished products of archaeological interest already catalogued were as follows: quarry No. 173 Gioia Piastrone; 155 Lazzareschi; 167 Venedreta A; 177 Artana; 162 Calagio; 113 Vara; 100 Bocca di Canalgrande; 92 Fantiscritti B; 89 Strinato; 79 Carbonera; 78 Tagliata; 40 Facciata.

In November 2021, a further survey of the situation was made by the undersigned and Giovanni Gatti, which led to an increase in the number of quarries affected by archaeological emergencies and to a quantification of more than 80 pieces of material lying at active quarries, many of which have nota lapicidinarum. Taking into account that these are quarries in full operation and that there has been no recovery of materials since 2009, it seems clear that this situation guarantees neither adequate protection of the finds nor their permanence at the sites of discovery.

Given the absolute and inexplicable inactivity of the relevant municipal offices in the field of protection (culture sector and marble sector), it must be noted that on the part of the Municipality of Carrara there has long been no intention to apply the Marchetti Ordinance (3.2.1989) still in force regarding the recovery of these materials and their delivery to the Marble Museum.

Since materials of archaeological interest found in the territory are subject to the laws of the State and of the Region of Tuscany to which the Municipality of Carrara must be subject (beyond what is also provided for in the Marchetti Ordinance) we note that in Carrara, in the matter of archaeological emergencies, in our opinion an irregular and scandalous situation has been created, the people responsible for which will have to be called to account.

However, the situation could be resolved by bringing to the Marble Museum the most significant materials, also from the epigraphic point of view, and by creating for the others a specific equipped area for collection, protection and enjoyment, which could also be identified in the area of the quarries in a suitable and specially equipped place.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.