While in a small town in Brazil they were finishing pulling up a circa 1:3 scale replica of the Trevi Fountain, in Italy the Court of Florence recognized the existence of a “right to the image of cultural heritage” by letting the Galleria dell’Accademia of Florence win its case against a publishing house that had published an image of Michelangelo’s David for advertising purposes, superimposing the photo of a model over that of the Renaissance masterpiece. Beyond the damage of a patrimonial nature (images of the works of state museums are, as is well known, subject to a reproduction fee if the use is for promotional purposes), the Florence court also recognized a kind of image damage, since the publishing house, as stated in the judgment, “insidiously and maliciously juxtaposed the image of Michelangelo’s David with that of a model, thus debasing, obfuscating, mortifying, and humiliating the high symbolic and identity value of the work of art and enslaving it for advertising and editorial promotion purposes.” In essence, the publisher’s action would have harmed the right to collective identity of Italians who find in Michelangelo’s David a symbol of belonging to the same nation.

The conception of cultural heritage that emerges from the Florence court’s ruling seems at least anachronistic, as much on the ideological level as on the practical and managerial one. Remaining on a purely ideal level, the idea that the David can be an “identity” symbol of the nation immediately raises a question: to whom does Michelangelo’s David belong? Is it really possible to consider it a symbol of the Italian nation? Or is it rather a universal good? If it is necessary to remain on the “identity” level, then it will be necessary to point out that the birth of Michelangelo’s David is linked to a precise historical moment, that of the years of the Florentine Republic, and the Florentines of the early sixteenth century saw in the biblical hero a kind of allegory of the free and republican Florence that managed to free itself from Medici tyranny. But also on a personal level Michelangelo identified with David, because for him the work had a strong intimate meaning, since the artist saw his personal story as one of struggle against adversities greater than himself. In the words of one of the greatest art historians of the last century, Irving Lavin: "Michelangelo’s David has achieved a unique status as a symbol of the defiant spirit of human freedom and independence in the face of extreme adversity. This emblematic prominence of the David is due in large part to the fact that Michelangelo incorporated, in a single revolutionary image, two constituents par excellence of the idea of freedom, one creative, and therefore personal, the other political, and therefore communal." How, then, can one say that the David is a symbol of the Italian nation, which, moreover, did not even exist at the time, except perhaps in nuce in the minds of a few thinkers? Why deny an American, French, Swiss, Chinese, Senegalese, Argentine, or Australian citizen to identify with the values embodied by the David if he considers the work close to his feeling? What good does it do to juxtapose Michelangelo’s David with a supposed “national identity,” if not to feed a stale, 19th-century nationalism that feeds on icons? It is, to cut a long story short, nothing more than cultural sovereigntyism.

On a practical level, the ruling is anachronistic because it goes in the opposite direction from the most up-to-date and contemporary positions in the debate around reproductions of cultural heritage, and in part it also goes against the guidelines of the Ministry of Culture itself, which last summer published a National Plan for the Digitization of Cultural Heritage, which among its objectives includes broadening the forms of access to cultural heritage, and which states among other things the need to to coordinate, streamline and simplify procedures for accessing and reusing digital reproductions of cultural heritage. “The dissemination and reuse of digital resources,” the plan states, “represent powerful multipliers of wealth and are strategic tools for the country’s social, cultural and economic development.” Not only that, the Plan also addresses the issue of the licensing and concession system, clearly reiterating that the current system based on the single image should be overcome by applying licensing policies aimed at the concept of “service” rather than “product.” How are the Open Access guidelines reconciled with the fact that the Florence court ruling would seem to subordinate public cultural heritage to a random “symbolic and identity value”? Does every use of the David image require an official to determine whether a reworking offends someone’s susceptibility? Should a Duchamp who puts a mustache on a Mona Lisa be fined? And, indeed, is the Mona Lisa that many care about an Italian identity symbol even if it is preserved in France? Then what about Open to Wonder and the Venus influencer contrived by the Armando Testa studio for the now famous marketing campaign of the Ministry of Tourism? Since most have been outraged by the use that has been made of the Venus, should the Uffizi sue the Ministry (thus the state should sue itself)? To what extent can it be determined whether the use of an asset mortifies it or not? Does a judge decide that? So do we have to clog the courts every time someone decides to advertise with the image of a public artwork in order to determine whether a specific and particular use injures our feeling of belonging to a nation?

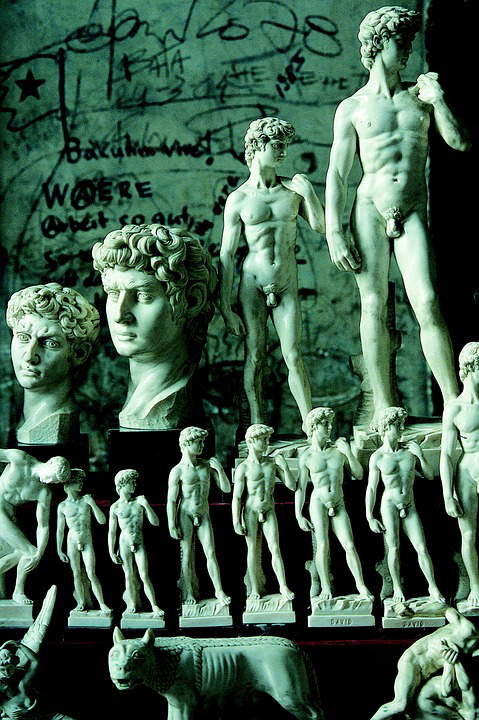

The ruling then triggers an obvious short-circuit when we consider that it was issued by the court in the city where every store, every store, every restaurant displays a reproduction of one of its most famous works. What to do with the thousands of reproductions of the David and Venus on souvenirs for tourists? Do they all have to ask for permission? What do we do, send ministry officials after the Davids who will invariably find themselves outlawed, since some might not like the fact that the august member of Michelangelo’s masterpiece is stamped on tons of goliardic aprons, or might find it detrimental to the dignity of the David that it can simply be reproduced in a plaster miniature and thus end up in the most extravagant destinations? Already now, as the Court of Auditors has also noted, in some cases the “ratio of costs incurred in the management of the collection service to the actual revenue generated has a negative balance,” i.e., the cost of the staff who have to manage the collection of concession fees is higher than the income from the fees themselves. And all this while, paradoxically, there is a debate in Scotland about the use of an image of the David to advertise a restaurant not because seeing the David with a slice of pizza in his hand is detrimental or not to his dignity (nice that the Ministry of Tourism did the same with Botticelli’s Venus), but because someone was outraged at the idea that the genitals of Michelangelo’s sculpture could appear in some posters hanging on the subway. That’s it: that’s also why we need to circulate the image of David much more, instead of orienting to positions that might limit it.

So much for “cutting-edge ordering,” as someone wrote after the ruling was issued: we are taking resounding steps backward. First with the ministerial decree on reproductions, a measure that will result in plunging us back into prehistory while all around us the world is questioning how to facilitate access to culture (and facilitation also passes through the free reproduction of public heritage images). That is, while around us the world is moving forward. And now with a ruling that introduces a kind of protectionism on public cultural property. It is the exact opposite: we have all of a sudden ended up in the rearguard. And we need to get back on the path to the contemporary world as soon as possible.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.