OnTuesday ,Apollo Magazine, one of the most influential international art publications, launched a discussion: should museums display artwork that uses live animals? Answers to the question were given by Victoria Daley, a Los Angeles-based writer and curator opposed to the practice, and Giovanni Aloi, editor of Art and nature magazine , published by the University of Minnesota Press, favorably. The topic is topical and interesting, and we offer below a translation of the positions of the two critics (edited by Ilaria Baratta), raising in turn the question: is it right to exhibit live animals at museums or exhibitions?

No, it is not right: the position of Victoria Daley

Everyone can understand this question from different points of view, but in any case the answer is the same: No.

Before addressing this question, we must start with an assumption inherent in the question itself: whether a work that uses live animals is really art. Or rather: showing live animals as works of art demolishes the meaning of art, while relegating living creatures to the unacceptable category of objects. Artists, who are called upon to invent and interpret, to transform and transform, must recognize that introducing real animals into a work of art is not an artistic action, but literal it negates the creative, interpretive and imaginative act necessary for the making of art. Animals can be painted, but substituting a living, breathing creature for a work of imagination is prohibited by definition.

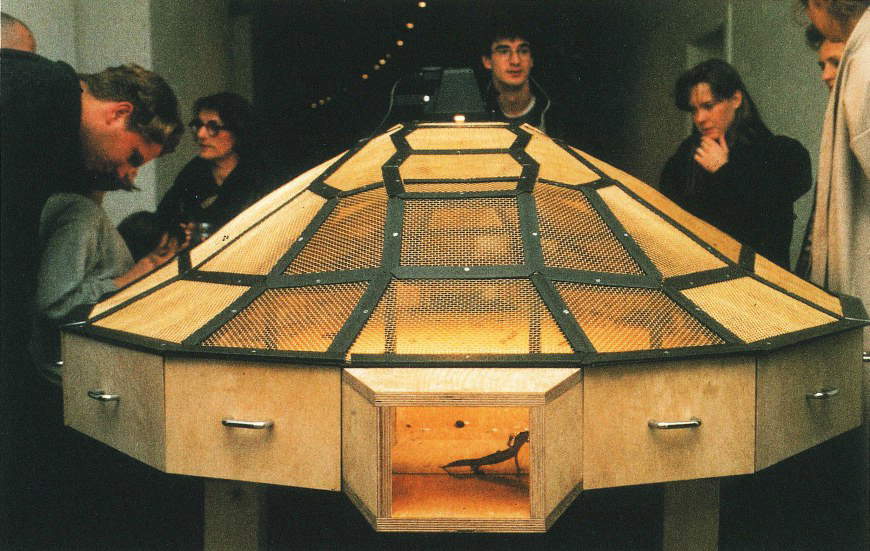

The ethical treatment of animals has become a topic of discussion in many areas in recent decades. Currently, the films state that no animals were mistreated during filming. Animals destined for the slaughterhouse are often offered better treatment in the last moments of their short lives than they receive during the rest of their existence. Many animal shelters carry out no-kill policies. Zoos have modified their spaces to create more natural environments for their guests, while circuses have been closed due to public demands to end animal abuse. Museums, holding anarrière-garde position, have not expressed clear policies on live animals. Perhaps because artists and museums often consider themselves exempt from various restrictions they are able (rightly) to present many controversial issues in the name of artistic freedom and free speech. However, they should not abuse these privileges by using live animals. When they do so, they turn their power into that of a bully the one whose code of ethics is the reason of the strongest. It would be commonplace to consider tattooing pigs, coloring a dog pink or sticking computers to the backs of turtles forms of cruelty; yet artists have done all these things.

No arrogant lickspittle can subject animals to abuse, but when an artist does it, and calls this act art, he loses the right to be called an artist. In post-Darwinian theory, in which the genetic affinity between humans and animals is fully recognized, relegating animals to involuntary service in the name of art would be looked upon with aversion, not allowed.

The art world is typically in favor of extending rights to as many living beings as possible; strangely, however, there are those who advocate a macho, speciesist philosophy of domination, subjugation and control over sentient beings who have nothing to say about it. Like sexism or racism, speciesism is something that needs to be overcome, not an artistic fad to be supported. Let us remember that at one time the issue of abolishing slavery also plagued humanity. Men wasted much time and lives battling over issues that now seem ridiculous to us (we always treat the past with condescension, not understanding that we are living it). The benefits, in hindsight, often blind us to the present; no doubt our descendants will look back and condemn our rude thoughts and habits we did not take seriously including the use of live animals in art as metaphors, symbols, supports and tools.If explanations and morality fail to convince, then for no other reason than mere goodness should museums refuse to display live animals? Until we truly understand the emotions of animals, would it not be prudent and courteous to extend to them the benefit of our doubts? Do they already bear the burden of being eaten, subjected to experiments, removed from their habitats, hunted for sport or to take body parts, cloned, forced to fight, compete and perform because artists must enlarge the ranks of those who inflict torment? Should we consider living animals provisions of art? Does art now override the animal kingdom and take priority over life itself? If museums support the inclusion of animals in the artworks they display, answer these questions with a “Yes.” They should be encouraged to answer with a firm No.

|

| Pierre Huyghe, Untilled (2012-2013) |

|

| Wim Delvoye, Linda (2006) |

Yes, that’s right: the position of John Aloi

Freedom of speech has historically proven to be a powerful tool for the emancipation of oppressed minorities. More recently, however, in the age of social and post-truth, we seem to forget too easily the basic principle that should govern its practice: accountability.

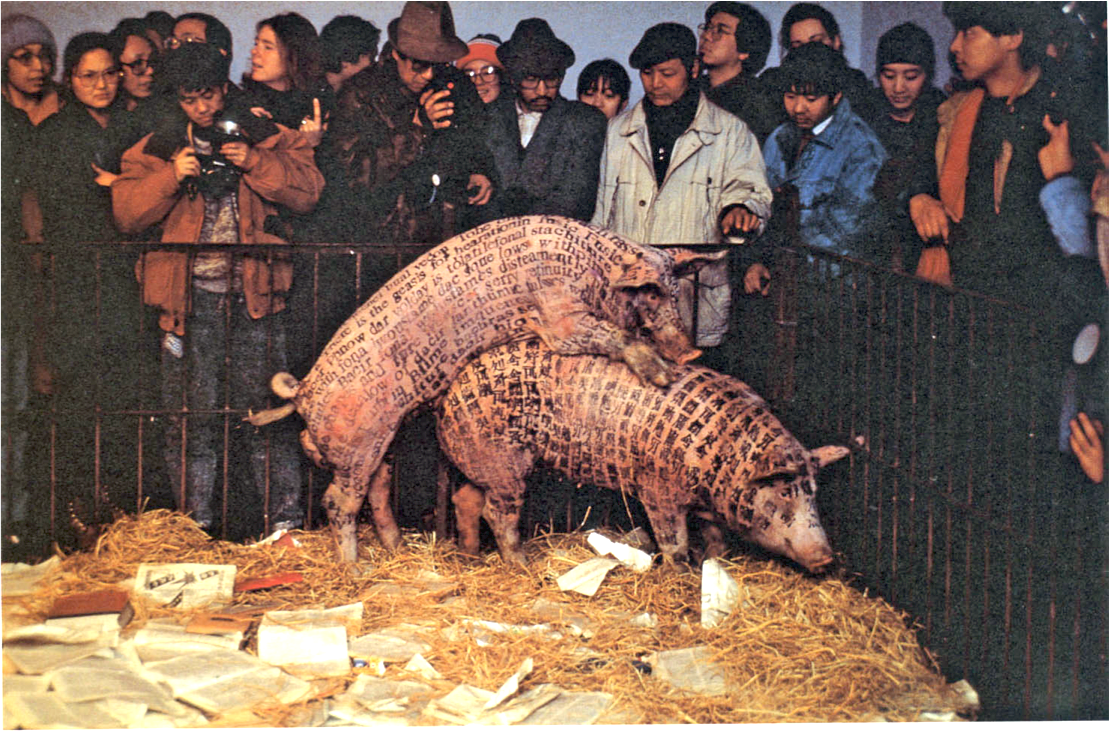

Last fall, the intentional inclusion of three works featuring animals in a retrospective of contemporary Chinese art at the Guggenheim in New York led to unprecedented protests. Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003) by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu is a video work in which pit bulls harnessed to treadmills wrestle each other to the ground in fierce pursuit; A Case Study of Transference (1994) by Xu Bing documents a performance in which two pigs mate in front of an audience; and Theater of the World (1993) by Huang Yong Ping is an enclosure in which insects, lizards, snakes and spiders eat each other.

After the protests, the museum issued a press release that stated, Freedom of expression has always been and will remain a core value at the Guggenheim. Nevertheless, Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World went on without the works that provoked the protests. Now the museum’s recent purchase of Xu Bing’s work, in addition to the repurposing of the exhibition at the Guggenheim Bilbao, is reigniting controversy. Is this a deliberate provocation? A desperate cry for publicity? Or a political hint at international art voices including Ai Weiwei criticizing the museum for collapsing under pressure? Does the Guggenheim hope the country of bullfighting will find these works less troublesome?

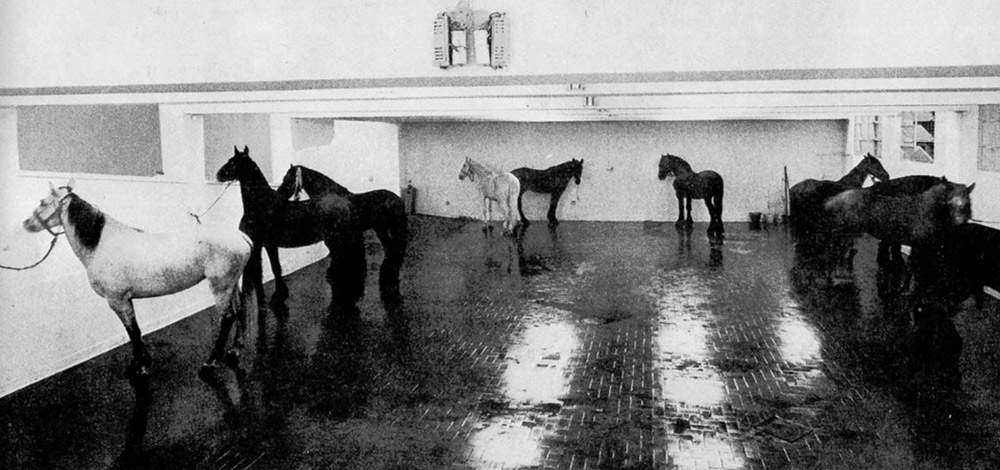

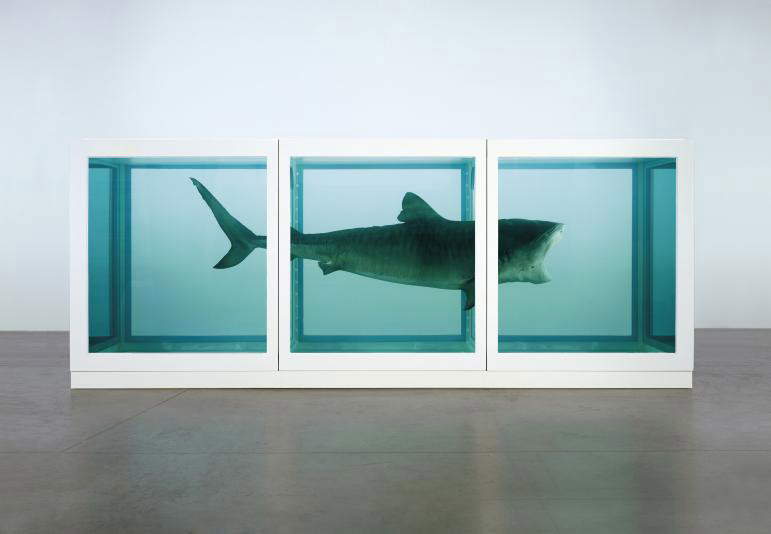

From Jannis Kounellis’s 1969 tethered horses and performative encounter with a coyote in a New York gallery by Joseph Beuys in 1974 to Damien Hirst’s cows and snakes suspended in formaldehyde in the 1990s, animals, good or bad, attract a lot of attention. They challenge the modernist purity that still lies at the heart of a gallery. In many classical and contemporary productions, animals represent our shadow the irrational, the unpredictable, the instinctive and the primal.

Considering how much art has changed in recent years, it is not surprising that audiences might now find some works distasteful. However, the unusual resonance of the Guggenheim controversy (over 800,000 signatures collected) has complicated the issue. On the one hand, we need to take into account the difference in animal ethics-related behaviors of culturally and geographically remote countries; on the other hand, the urgency imposed on current issues by climate change and mass extinction is rapidly shifting common frames of reference. With the growing realization that our relationship with nature has been characterized by unproductive clichés, a new level of knowledge, understanding, and responsibility is being reached.

In these works, animals replace themselves. They are nations, peoples or anonymous pawns in a capitalist system; animals as humans: it is now an old game and no longer interesting. Allegory, the sphere of classical art, today requires a more sophisticated orientation to engage and impress the audience. Today’s audiences keep their gaze fixed through the faint metaphorical veil and all they see is animal abuse. Moreover, the works of Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Xu Bing and Huang Yong Ping implicitly turn the visitor into a sadistic voyeur. Is it necessary to see animals eating each other to contemplate the thoughtlessness of capitalism? Is watching two pigs mating a new and nuanced way to conceive of international affairs? Is tormenting dogs a creative way to reflect on power and control? China has much more interesting and thought-provoking contemporary art to offer, and a few such works are indeed found in the Guggenheim exhibition.

However, we should not generalize: not all works using animals are to be demonized. The works of Beatriz da Costa, Mark Dion, Pierre Huyghe, Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, and Ren Ri, to list a few, speak differentially to contemporary audiences because their theme is the human-animal relationship. The presence of animals in a gallery is justified by the meaning of the work and actively provides an opportunity to give serious consideration to our existence with them. These artists gain knowledge about animals and ensure that the gallery is suitable for their well-being; their works engage, provoke, re-imagine and educate. These are unlikely to have the same protests as the works exhibited at the Guggenheim.

|

| Xu Bing, A case study of transference (1994) |

|

| Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the world (1993) |

|

| Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (1969) |

|

| Joseph Beuys, I Like America and America Likes Me (1974) |

|

| Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) |

|

| Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, From here to ear (1999-ongoing) |

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.