I feel deep embarrassment when I read certain hasty and superficial judgments about the wave of protests of the Black Lives Matter movement that has swept through Anglo-Saxon countries and, to a lesser extent, the rest of the Western world. I find this natural: from our position as affluent white (and perhaps male and heterosexual) people, we cannot empathize with the anger of those who are demonstrating or those who go so far as to tear down controversial monuments. I believe, quite frankly, that it is impossible for us to walk in the same shoes as those who, for centuries, have suffered abuse, discrimination, injustice, and still continue to suffer situations of inequity and disparity. However, we have a duty to understand the reasons for this anger, to study it, analyze it, describe it, tell about it, and possibly support it, because I believe it is an inescapable commitment to have a more just society. It is a rage, however, that stems from reasons that are both historical and contingent, which are tremendously complex and intricate, vary from country to country, from city to city, and affect different aspects of our societies: the discussion about monuments is but one of the many levels on which the discussion is being addressed.

A discussion that should have been started long ago, that has long been treated with indifference: now, however, the negligence of the past presents a bill that takes the form of defacement, devastation, demolition. And if we see statues in pieces or thrown into lakes or harbor waters, I think the fault lies mainly with those who for too long have neglected public reflection on the role of monuments in contemporary society. This is also true for Italy: perhaps we will not witness the scenes we have observed in the United States and the United Kingdom, because we live in a totally different context, but the fact that even here the first defacements have already begun and the first requests for removal have started, should push us to reflect on the fact that our country cannot believe that our monuments are safe. It is a discussion that even now, however, we are struggling to address at a high level and on which, in any case, we are suffering from the culpable delay of politics and the generalist media, which for years have been nailing the public debate to economic or judicial news, without deviating from it, and considering culture, at most, a handmaiden of tourism.

Not that opportunities for discussion have been lacking in recent years: suffice it to recall, however, how the mainstream media completely snubbed the last Venice Biennale, where the racial theme was among the main planks of the event; suffice it to recall how the improvised and demented proposal to erase Mussolini’s name from the obelisk in the Foro Italico was treated, treated at most as a topic good for some soon-to-be-forgotten Internet flame, suffice it to mention an entire International Sculpture Biennial in Carrara (the one in 2010), centered precisely on the theme of the legacy of monuments, and which for most newspapers was at most an item to be included in the bulleted list of things to see on the weekend.

These shortcomings, which affect Italy as well as the rest of the world, now turn into the most violent outcomes of the protest. It is therefore easy (and perhaps even hypocritical) to brand as hooligans and vandals the small groups of protesters who are attacking statues in public spaces, and from which even part of the Black Lives Matter movement has disassociated itself: it is a moment of strong emotions and mounting tension, and what we can do is try to understand the reasons for the gestures, which are not all identical and do not all mature in the usual contexts: some (such as last weekend’s defacements in Turin) are impromptu and gratuitous gestures, while others, such as the demolition of the Edward Colston monument in Bristol (which, moreover, has already been fished out of the waters of the English city’s harbor and will be musealized) are the result of exasperation that comes after so many requests and so much urging. The gesture is therefore understandable, but observers should not excuse it. In other words, what we cannot do is justify the cullings (and, consequently, legitimize a violent act), as many intellectuals of a left-wing that, by dint of the reckless and maximalist positions of its opinion makers, condemns itself to an increasingly mournful irrelevance are doing in recent hours. If we still want to live in a space that respects the rules of civil discourse, we cannot give ease to subversion, because that is what it is all about after all.

|

| The tearing down of the Edward Colston monument: the moment the bronze statue is thrown into the waters of Bristol Harbor |

|

| Turin, the monument to Victor Emmanuel II at the Palazzo di Città daubed. |

Especially if the demolitions are then deemed a “possible gesture,” as Roberto Saviano has written, when the monument in question is considered “a nasty statue from 1895”: “often the historical interest of a building or a statue,” Saviano justifies, “is enough to make it lose its intrinsic symbolic value, leaving only the value of testimony and study.” And so, the writer argues, the Colosseum, given its enormous historical relevance, can safely stay in its place, despite the fact that we all know that “people were killed in its arena for fun.” However, Saviano’s, who is not an art historian and (at least to my recollection) has never been involved in art history, is an argument that does not take into account the fact that historical interest is not unmoved over time and, conversely, does not take into account the changing significance of a work over the centuries (or does, but contradicts himself at the moment when he believes that the Bristol statue is not interesting). This is a concept that was already recognized in the nineteenth century by Alois Riegl, who distinguished between monuments erected for purely celebratory purposes (the Colston statue) and works that were erected to serve practical purposes, but which acquire considerable historical value as time passes (the Colosseum). Thus, a first problem arises when the intentional monument also acquires historical value over time, as is the case with the Bristol “bad statue,” which is classified as a Listed building, i.e., as a listed monument of cultural interest, and thus protected by the preservation bodies. A further demonstration of the fact that, apart from a few examples on which everyone agrees, our concept of “masterpiece” or “interest” is decidedly labile, just as in varying and different ways our sensibility can respond to a work of art, more developed for some, and less marked for others.

Another problem lies in the impossibility of separating the historical and symbolic value of a work from its artistic value, reasoning that the symbolic importance of a monument does not decrease proportionately as its aesthetic value increases (if that is the sense in which the pejorative affixed by Saviano to the Bristol sculpture is to be understood), and vice versa: therefore, the fact that the Flavian amphitheater is one of the most significant architectural testimonies of ancient Rome does not make it any more bearable to know that so many women and men lost their lives there for the delight of the crowd. In other words, we cannot establish lists of monuments to be torn down or left standing on the basis of their aesthetic value. For that matter, it will be appropriate to remember that Riegl was also aware that the so-called “artistic value” is a construction of the person looking at the work today, and consequently this too is a value that could change with the passage of time. All of this is without calculating that in cases like these we look more at the gesture than at the value of the work, which is why a crowd of troublemakers at the height of a demonstration might not care whether they are in front of a cheap work or a masterpiece (iconoclasts tend to take into account only the symbol).

We cannot, therefore, reason about the symbols embodied in monuments without losing sight of the contexts and without addressing the discussion in all its ramified complexity, which here I have attempted to introduce in a quick and crude manner: to pose the question only from the point of view of symbols is to endorse a dangerous drift that can legitimize the demolition of any work and place on the same level works that are distant in time and objectives. In Bristol, a demonstration was held in front of the statue of Colston, a slave trader celebrated as a benefactor and philanthropist, since with the meager proceeds of his human trade he financed the construction of schools, a hospital, and shelters for the elderly, and still today, in the port city, there are streets, buildings, and even bars named after him. In Livorno, tomorrow, he will manifest himself in front of Pietro Tacca’s Four Moors group, an early 17th-century bronze masterpiece, the work closest to the Bernini sensibility of his time in Tuscany: it is a work about which much has been said, since at first glance it disgusts us, as it should, to see four black men chained beneath a triumphant white male. But it is also a work that has nothing to do with Colston’s statue, since it was made to adorn the base at the monument of Ferdinand I de’ Medici and pay homage to his victory over the Barbary corsairs, depicted as slaves in chains because such was at the time the end that the “prey” of the corsair exploits of the Knights of St. Stephen met, but it was also the fate of the inhabitants of the Italian coasts who were captured by Muslim corsairs and in turn enslaved in the pirates’ homelands.

This is the complexity that we risk losing if we refuse to look at the works from all aspects. Simplification risks running us into a serious danger, that of cleaning up history. Tearing down a monument also means erasing what has been: and so it will be appropriate to reiterate what we wrote last year on these pages about the obelisk in the Foro Italico, since the sense of discomfort with this undoubtedly inconvenient work continues to haunt us. In today’s Manifesto, Alessandro Portelli has written words that could be perceived as contradictory, rightly recalling that monuments and works of art change in meaning as historical times change, but at the same time asserting that the obelisk in the Foro Italico, being a monument erected to convey “a message,” only imposes its memory over all others. But this imposition is impossible at the moment when history reminds us what fascism was: the problem, if anything, is to make the past evident. And so, in the article on the obelisk, we were reminding that we are out of time for campaigns to remove symbols, but we are in time for a serious awareness of the problem and to insist “on education and didactics, reflecting on targeted commentaries, on exhibition routes, on documentation and research centers, on school programs, on exhibitions and museums that can offer us concrete help to face with greater serenity a thorough reflection on our recent past”: in essence, we are in time for a critical reflection in our past. We should, in essence, be concerned with integrating what is there, rather than manifesting intentions to erase.

|

| Giovanni Bandini’s statue of Ferdinand I and Pietro Tacca’s Four Moors in Livorno. Ph. Credit Giovanni Dell’Orto |

|

| The obelisk at the Foro Italico |

|

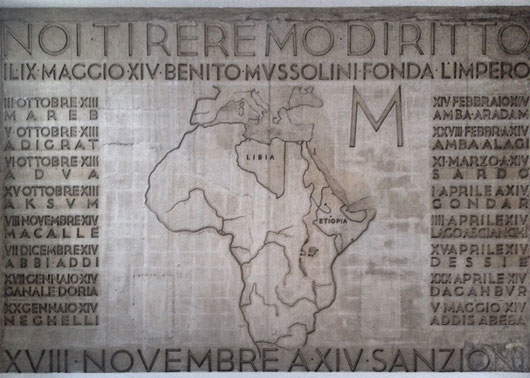

| The map of Africa at the Casa della Gioventù Italiana del littorio in Rome. |

In this sense, I find very valuable the reflection of Igiaba Scego (who as an Italian of Somali origin should feel annoyed more than anyone else by the presence of that obelisk), who in one of her articles in Internazionale recalled Gianni Rodari’s position: “you want to leave the Mussolini inscriptions? Fine. But let them be properly completed. Space, on the white marbles of the Foro Italico, is not lacking. We have good writers to dictate the continuation of those epigraphs and skilled craftsmen to engrave the additions.” Of course, we don’t have to remake the Foro Italico, but we do have to frame it in a different narrative, as was done in 2019, Igiaba Scego always reminds us, at the House of the Italian Youth of the Littorio, inside which is a map of Africa marked only with Italian possessions and marked with Mussolini’s M. “That map,” Scego wrote, “leaves one baffled by its ferocity, but to pick at it would be a great mistake, because just by looking at it one understands so much of the nefarious vision that fascism had of the world, especially of those peoples who had unfortunately come under its rule. That blank map still speaks to us today of the violence that was meted out to the bodies of the colonized.” So, a collective of postcolonial and feminist scholars last year “flooded it with sentences, projected or put there through placards, and in parallel organized public debates. The void was filled with questions such as: is my skin a privilege? Who is civilized? Who is superior? Are Italians white? What language do your ghosts speak? Where is Somalia? Where is LEtiopia? Where is Eritrea? Who can speak? Is the homeland a woman? Why is this map of Africa empty?”

The same could be done, then, with the uncomfortable legacies of the past: not erasing them or removing them, but contextualizing them, enriching them, telling them in a different way, of course evaluating on a case-by-case basis, because the discourse is too complex to be applied in the usual way to all monuments. Certainly, culling is not the solution. There has been much discussion these days about the monument to Indro Montanelli, erected in 2006 at the ramparts of Porta Venezia in Milan. In this case we could also drop all the reasoning addressed so far, since it is a very recent work. However, there are resistances, even from the center-left: what to do then to contextualize the work of a great journalist who, however, has never regretted abusing his position as a male colonizer to do, he twenty-five years old, his sordid convenience with an Eritrean girl forced to madamate? Don’t erase it, don’t deface it, and don’t even remove it to put it in a museum: as Igiaba Scego suggests, why not put another work alongside Montanelli’s statue that reminds us of the violence all sexually abused little girls suffer?

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.