This article, originally published in Artsy, unpublished in Italy and translated by us by kind permission of the author, is dedicated to the memory of Barbara Steveni, artist co-founder of the APG group, who passed away last Feb. 26.

It was not a classic presidential election campaign. There were no flags, no podium, no baseball caps that read “Make Cuba Great Again.” Cuban artist Tania Bruguera, sitting on an office chair in an empty room, was talking to me via video conference during a meeting at the Creative Time Summit in October 2016 when she said she would run in Cuba’s 2018 presidential election.

If there was ever a time when the world needed artists, that time is now. Society needs their radical ideas, their visions, their perspectives. I trace this idea back to the British artist, educator and provocateur John Latham (Livingstone, 1921 - London, 2006), who devoted his life to creating a worldview capable of uniting science with the humanities.

Latham believed that the world can only be changed by those willing and able to conceive of reality in a holistic and intuitive way. And the individual best equipped to do this, Latham suggested, is the artist. And to that end, Latham was among the founders of the Artist Placement Group (APG), along with Barbara Steveni, Jeffrey Shaw, David Hall, Anna Ridley, and Barry Flanagan: it was an initiative to expand the reach of art and artists into society.

Latham’s disdain for boundaries between different disciplines was underpinned by the “flat time theory,” a philosophical way of conceiving time that he developed throughout his lifetime. This theory proposed to steer us toward a cosmology based on time (and which would consist of aligning social, economic, political and aesthetic structures as a sequence of events by recording their cognitive patterns), abandoning our usual worldview, which is sensory and space-based. Believing that linear and accumulative knowledge of space and history was a farce, Latham proposed an “event structure” that radically reconfigures reality, enabling an understanding of the universe that simultaneously embraces all disciplines.

I first interfaced with the brilliance of Latham’s work when Douglas Gordon took me in person to the Flat Time House, what was then Latham’s residence in Peckham, South East London, in 1994. Gordon wanted that meeting badly, and indeed the recording of that visit (which has been found in my archives) begins with Gordon and me in a cab as we set out to meet Latham.

|

| John Latham, Five sisters (1976), shown in the exhibition A World View: John Latham (London, Serpentine Gallery, March 1 to May 21, 2017). Ph. Credit Luke Hayes. Courtesy Serpentine Gallery. |

As we talked, Gordon explained how he had been influenced by Latham’s description of the “Accidental Person,” a figure whose role in society would be to develop new ways of thinking, and who would support the GPA’s mission of placing artists in key positions in society itself. Five Sisters is a work he made in collaboration with Richard Hamilton and Rita Donagh: its intent is to document the GPA’s residency at the Scottish Office, which had declared five large coal mining waste deposits a monument (or, rather, anti-monument). Latham suggested that those deposits should be protected as monuments and, indeed, that they should be accorded the status of cultural property. On the occasion of John Latham’s exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries, we had reactivated the APG and had invited artist Pedro Reyes to dialogue with various departments of the London City Council.

Gordon was fascinated by the idea that boundaries and social patterns were fluid, and that “none of us are particularly tied to the time or space we are in.” It is a radical idea because it shows that change is possible, and that it can happen suddenly.

Through such a radical legacy, Latham can be seen as a proto-artist of our present: he believed that the artist plays a specific role in society, that of building a free space in which radical ideas can be explored.

In this sense, Latham’s work is very close to that of Joseph Beuys. Beuys was equally linked to a view of democratizing art: as is well known, he had declared that “everyone is an artist,” and taught us that art, like politics, is something in which we all participate. Beuys’ “extended definition of art” included the idea of social sculpture as Gesamtkunstwerk, for which he claimed a creative and participatory role that could shape society and politics. As it was for Latham, Beuys’ trajectory was accompanied by passionate, sometimes even bitter, public discussion. Beuys made his life and work an ongoing public debate to discuss radical new ideas. Beuys demonstrated how art can provide society with the space it needs to be able to imagine.

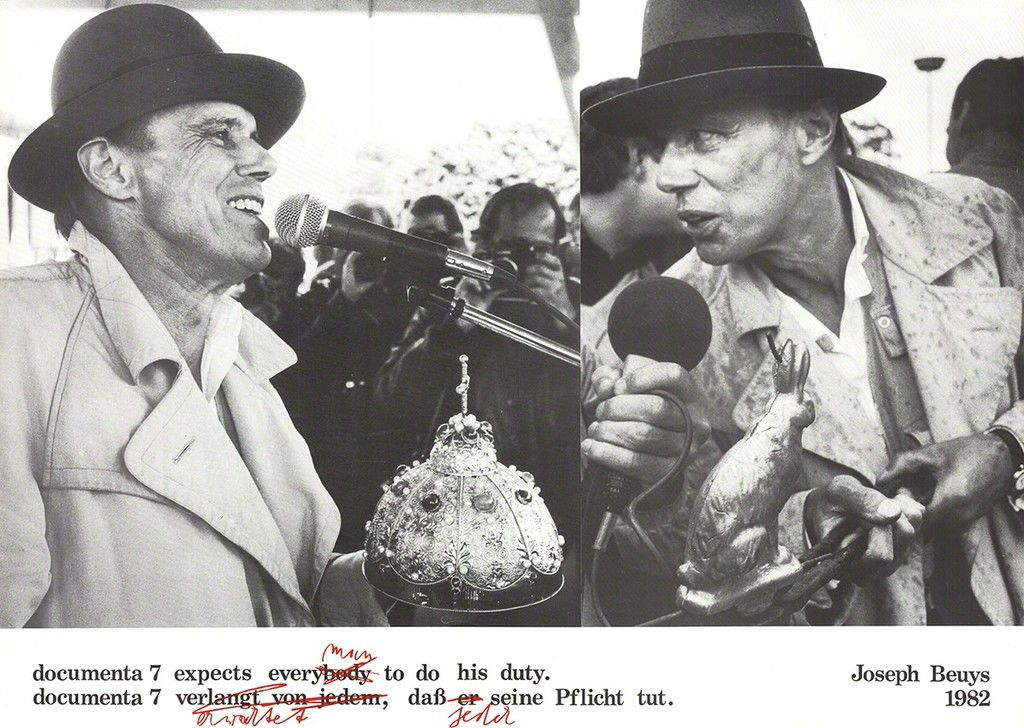

|

| Joseph Beuys at Documenta 7, 1982 |

And as with Latham, for Beuys his lectures, political activism and actions opened up that “agonistic space” recently identified by political theorist Chantal Mouffe as vital to the practice of democracy. Mouffe argues that democracy should admit difference and diversity (which necessarily lead to controlled conflict), rather than seeking consensus. This “agonistic” approach is intended to encourage, rather than suppress, antagonistic debate. I think it can be related to Edouard Glissant’s ideas on homogeneity, diversity, and globalization, which were also very important to my own thinking. We need to recognize and encourage differences. Only when we do so is it possible to give birth to a democratic society.

Latham and Beuys, among others, taught us that art is a space in which real debates can be conducted, and they also taught us how this can be translated into political action. During his lifetime, Beuys founded or co-founded the following political organizations: the German Student Party (1967), the Organization for Direct Democracy through Referendum (1971), the Free International University for Interdisciplinary Creativity and Research (1974), and the more famous German Green Party (1980). When I was a teenager, I came across a lecture by Beuys. He talked about “reality production,” about social sculpture, about founding a Green Party. He called society a “sculptural structure,” meaning a structure that has to heal itself. He talked about how change is by definition a creative action, and how any progressive politics needs free thinking. In a society that has forgotten how to think creatively, change is impossible. Art, which teaches us to think creatively and imagine new possibilities, is essential to society and politics.

|

| A view of the exhibition A World View: John Latham (London, Serpentine Gallery, March 1 to May 21, 2017). Ph. Credit Luke Hayes. Courtesy Serpentine Gallery. |

Many artists over the past half-century have taken up the vision of Beuys and Latham, who saw the artist as a social actor. They are intellectuals who have inserted themselves into the social and political fabrics of their societies, and have been able to conceive of art as something that takes place within the life of the community (and not outside it).

Artist Bruce Conner, in 1967, ran for office as a member of the Board of Supervisors [a kind of provincial council, ed. His legendary campaign, in which his only statement was an oration on light, was meant to remind us that in a true democracy every voice should be heard, and no matter how far from the mainstream it is. It is also interesting to note that Conner, despite being a counterculture figure, voted in every election round and was very critical of his friends who did not vote. His campaign gave an option to those who were dissatisfied with the status quo. In this sense, art can be a magnet for a large portion of our electorate who do not feel represented by the options presented to them.

| Tania Bruguera’s October 2016 announcement. |

Edi Rama, the current prime minister of Albania, was a painter before he became a politician, and he remained close friends with the artist Anri Sala. We must consider his program in the context of Beuys’ social sculpture. In his vision, art is not separate from politics, but rather complements it. Edi Rama is “rethinking democracy,” as Sala told me. When Rama became mayor of Tirana, he said that that was “the most exciting job in the world, because it gives me a way to act and fight for good causes every day. Being mayor of Tirana is the highest form of conceptual art. It is pure art.” This story deserves a broader evaluation than I can offer in this short text, because it seems to me to be fundamental to our understanding of the topic of “contemporary art and politics.”

Rama stuck to those statements with his extraordinary “green and clean project.” Echoing the famous 7,000 Oaks project that Beuys brought to Documenta in 1980, Rama organized the planting of 1,800 trees around the city and introduced nearly 100,000 square meters of urban greenery. He also ordered that many old buildings be painted with what are now known as “Edi Rama’s colors”-a project chronicled in Sala’s extraordinary film Give Me Colors, a video that lies somewhere between documentary and artwork. They were very cheap, effective and enormously popular ways to improve the urban environment, and to change the dialogue around a city that had had a very troubled recent past. His view of the relationship between art and politics can be summed up in a quote of his that I find very inspiring: “culture is the infrastructure, not the mere surface.”

According to this idea, art and culture are not a luxury, but are absolutely essential components for the proper functioning of a society. Art is communication, participation, interaction, and any organization that does not promote these relationships is inevitably doomed to failure. When talking about painting the city of Tirana, Rama said that “interventions on buildings are not aesthetic interventions, but an attempt to reopen a communication between citizens, the environment and the authorities. Entering into a process of transformation means, first of all, trying to establish a sense of belonging to the community by creating signs.”

|

| Tirana, the painted buildings. Ph. Credit David Dufresne |

The idea of art as infrastructure, as “social sculpture,” has since been developed in exemplary fashion by Theaster Gates, whose expanded art practice includes projects such as the Rebuild Foundation, a nonprofit organization that seeks to introduce communal space-sharing and affordable housing initiatives for the underserved in his hometown of Chigago. It has transformed abandoned buildings into cultural institutions such as the Archie House, which holds 14,000 architectural books from a library that closed, or like the Stony Island Saving Bank turned Stony Island Arts Bank, a library that holds, among other things, the book collection of John H. Johnson, the founder of Ebony and Jet magazines, and the record collection of Frankie Knuckles, the father of house music. These spaces are open to the community, and are spaces where culture and political action are not only exhibited but practiced and promoted.

Artists’ political interventions can also take the form of provocation. Shortly before he died, Christian Schlingensief told me how much Beuys had meant to him. As a teenager in 1976, he had attended a speech by Beuys, and although he admitted that he did not understand everything at the time, he recalled how Beuys had provoked his father by predicting that the social system would collapse within seven years. Seven years later, Schlingensief asked his father if he remembered that prediction. “Yes,” he told him, “I wrote myself a note on the calendar, and it has been fixed there for seven years: now I can say that what he predicted did not happen.” But the really interesting and challenging thing, Schlingensief had pointed out to me, lay in the fact that Beuys had forced my father to think about the future for seven years. Art cannot predict the future, but it can act on the way we behave in the present.

Schlingensief’s production includes a series of actions and provocations intended to shake German society by making it think about its flaws. He once invited the entire population of Germany’s unemployed, who are in the millions, to swim in Lake Wolfgang, where Chancellor Helmut Kohl was spending a vacation. Schlingensief’s plan was to have these legions of swimmers overflow the lake to flood Kohl’s house, which was nearby. The plan could only have failed (and only about 20 people bathed in the lake), but it attracted great media attention, not so much because the idea was to flood Kohl’s house, but because it had addressed a problem of national importance in a manner specifically calculated to generate awareness. And this is one way artists can touch the institutions of power: it’s about organizing actions or interventions that manage to highlight neglected problems. We could also talk about the courage of Octavio Paz, who spent his whole life speaking out against totalitarianism and who left us these memorable words, “there can be no society without poetry.”

|

| Stony Island Arts Bank. Ph. Credit Tom Harris, copyright Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy Rebuild Foundation |

Poet and writer Eileen Myles has used humor to disrupt political processes. In 1991, she announced that she would run for U.S. president as the only “openly female” candidate. Her campaign, which started in the East Village, soon became a national interest project, an opportunity for those who could not make their voices heard in mainstream politics. Her participation in political processes was part performance project, part protest, part joke. Nevertheless, she demonstrated more political integrity she than any of the other candidates.

Our Do it project began in Paris in 1993 as a result of a discussion with artists Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier on how to organize more flexible and open exhibitions. They reasoned in particular about one point, namely whether an exhibition should be based on instructions written by the artists, which can be freely interpreted whenever they are presented. How can an artist’s work be transformed if others have created the artwork? For that project, Eileen wrote a text entitled How to Run for President of the United States of America. The text reminds us that, even in frightening times, democracy belongs to the people and art is a means to reclaim it: “you know? They really can’t stop you. With the exception of maybe a couple of states, one of which is Nevada, every citizen can run for office. In New York, for example, you only need 33 friends to collect the signatures necessary to sign a declaration that states that if you win, they get into your constituency. You can just call them from home, and they don’t even have to bring the papers with them. They can get them endorsed even from a travel agency. It’s not difficult.”

This text is an extended version of a talk I gave at the Creative Time Summit when Tania Bruguera announced her candidacy. In a country where democratic elections have never been held, her declaration had new meaning, following the passing of Fidel Castro in the month after she issued her announcement.

The decision was an extension of her project to address political and humanitarian problems in Cuba through performance and social movements. Tania practices “Arte �?til” (“useful art”) and has developed long-term projects, including a community center, a political party for immigrants, and an institution working for civic literacy and political change in Cuba. Bruguera describes “Arte �?til” in these words (and I think they are a good introduction to his work), “I really wanted to rethink the role of the art institution in terms of political effectiveness. I kept finding limitations while I was doing my work: however, in the process, I found a large group of artists and artworks that had already dealt with the same problems for a long time. I could identify them with what I called Arte �?til, because they did not just complain about social problems, but tried to change them by implementing different solutions. And they not only imagined utopian and impossible situations (which is what most artists do), but they also tried to build practical utopias.”

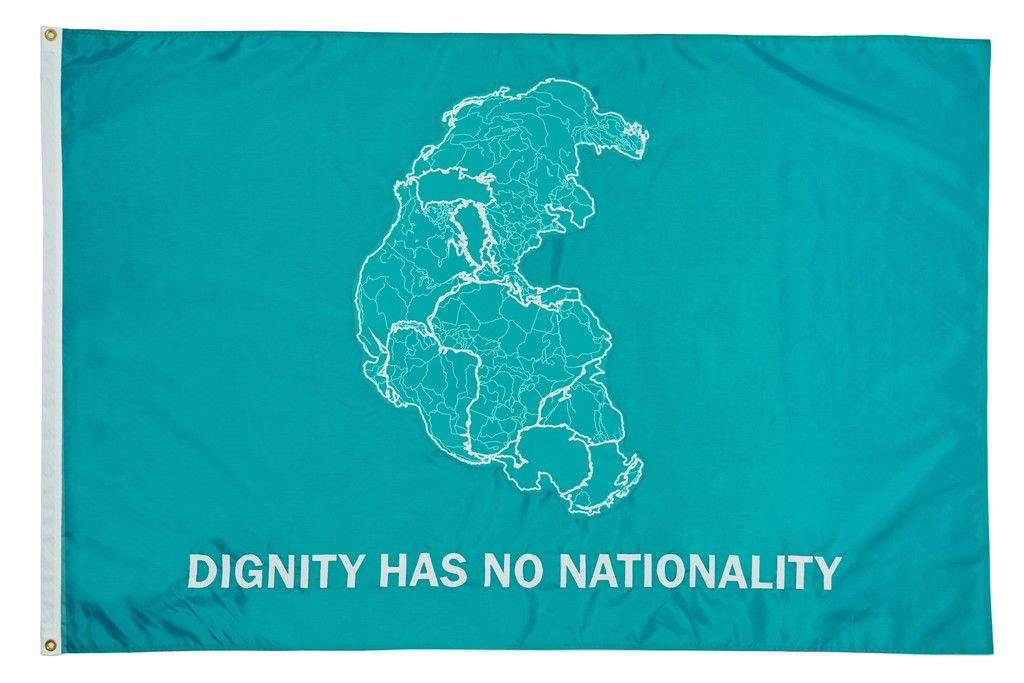

|

| Tania Bruguera, Dignity Has No Nationality (2017). Creative time: Pledges of Allegiance |

Tania founded the People’s Party of Migrants in 2006, with the aim of creating a new form of political organization, and then created the International Migrant Movement as a long-term project in the form of a socio-political movement. For his work, the artist spent a year putting into operation a flexible community space in Queens, New York, interacting with residents and international communities, while at the same time working with social services, institutions, and artists reflecting on how to reform immigration. Public workshops, events, actions, and collaborations encouraged immigrants to consider the values they shared with the community and to foster ties within the community itself. This was politics in art form, done on the ground, capable of changing lives.

In addition, Tania Bruguera created an institute in Cuba aimed at promoting civic literacy and advocating for political change. The institute, which considers itself a wish tank, employs public actions and performances with Cubanos de a pie (ordinary Cubans): from housewives to professionals, from activists to students. “It’s about,” the artist said in a description of this work, “building bridges of trust, not being afraid of each other, creating a peaceful and thoughtful response where there is violence, creating a place where people with different political ideas can be together.”

Tania Bruguera’s candidacy is, at the same time, the culmination of her work as an artist, and perhaps also an unconscious homage to the ambitions of the GPA, which placed the artist, as an “Incidental Person,” within existing social and political structures in order to initiate change. Tania is among those artists who apply the lessons left to us, for the present, by artists such as John Latham.

The author of this article: Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist (Weinfelden, 1968) è uno dei più influenti teorici, curatori e critici d'arte al mondo. Dal 2006 è direttore artistico delle Serpentine Galleries di Londra. Autore di The Interview Project, un ampio progetto di interviste, tuttora in corso, alle principali personalità dell'arte internazionale, è anche co-redattore della rivista Cahiers d'Art. È curatore di oltre 350 mostre: tra queste, il padiglione della Svizzera per la 14esima Biennale di Architettura di Venezia (2014), la serie Cities on the move (1996-2000), la serie The 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Rooms (2011–2015). I suoi studi più recenti riguardano i rapporti tra arte e tecnologia. Dal 2013, sul suo account Instagram (@hansulrichobrist) porta avanti il The Handwriting Project, protesta contro la scomparsa della scrittura a mano nell'epoca digitale. È presidente della giuria internazionale della Biennale Architettura di Venezia 2025. Vive e lavora a Londra. Foto: Jurgen TellerWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.