Last leg of our journey to discover fantastic animals and creatures in Italian museums. With the twentieth stage we arrive in the mountains of the Aosta Valley to see what creatures lurk in these parts. The project is led by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture with the aim of offering a different point of view on our museums, places that are safe and suitable for everyone. Safe travels and thank you for following us this far!

In the chapel of Sarriod de la Tour Castle, a medieval building located in Saint-Pierre, nestled among the vineyards beside the Dora Baltea River, you can admire a bicaudate (i.e., double-tailed) mermaid dating from the mid-13th century. In medieval churches and chapels, especially in northern Italy, it was not uncommon to find figures like this one: mermaids depicted in this way, with the upper half of the body as a woman and the other half as a fish, became widespread after the ninth century (according to Greek mythology, however, mermaids were half-woman and half-bird), and typically were a symbol of lust, one of the deadly vices, although we do not know for sure their allegorical meaning.

As many as 171 corbels carved into the ceiling, dating from around 1432: these are the ones that make up the unique decoration of the Hall of Heads at Sarriod de la Tour Castle. This decoration was commissioned by the owner of the castle at the time, the nobleman John Sarriod de la Tour, who evidently loved grotesque depictions, because alongside a series of portraits (there are ladies dressed according to the fashion of the time, gentlemen, knights), in this room you can also find characters in obscene poses but also animals and monsters of all kinds: so here is a griffin, a mermaid, a unicorn, the face of a satyr, a three-headed character, devils of all shapes and fantastic creatures that came out of the imagination of the anonymous carver who made this work.

The collegiate church of Santi Pietro e Orso in Aosta, also known simply as the church of Sant’Orso, is one of the most important medieval churches in the Aosta Valley, and it preserves two relevant fresco cycles: one from the Ottonian period, from the mid-11th century, created by Lombard-trained artists, and one instead from the late 15th century, which decorates the chapel of Saint Sebastian at the end of the right aisle. The altar lunette is decorated with a fresco depicting the Madonna and Child and Saints Michael and Anthony Abbot, by an artist whose identity we do not know. St. Michael, the commander of the angelic hosts, is portrayed as per typical iconography with his armor and sword, while holding the devil, defeated, at his feet. St. Michael’s adversary is depicted as a strange and funny being with a hairy body, horns and bird-like legs, sitting on the ground and held at bay by the saint with his sword.

The castle of Fenis is certainly the most famous of the manors found throughout the Aosta Valley, a fame that derives not only from its very recognizable appearance (it dates from work in the period between about 1320 and 1420), but also from the presence of interesting frescoes, such as those that were commissioned by the Aosta Valley nobleman Boniface I of Challant, who is credited with completing the castle. Perhaps the most famous scene in the frescoes is the one in the center of the castle courtyard depicting St. George saving the princess from the dragon. The work was created around 1415 and is attributed to the workshop of Giacomo Jacquerio, one of the most important Piedmontese painters of the time. Also on the fresco is the monogram of the commissioner, with the letters BMS, or “Bonifacium Marexallus Sabaudiae” (Boniface Marshal of Savoy). The fresco, in the International Gothic style, perfectly embodies the chivalric ideals prevalent in Piedmont and Val d’Aosta at the time: thus, St. George is not only a Christian hero, but an unblemished knight (depicted here, moreover, in the clothing of the time, despite the anachronism: according to hagiography, in fact, St. George would have lived in the 3rd century) who bravely and boldly confronts a fearsome enemy, saving the life of the princess.

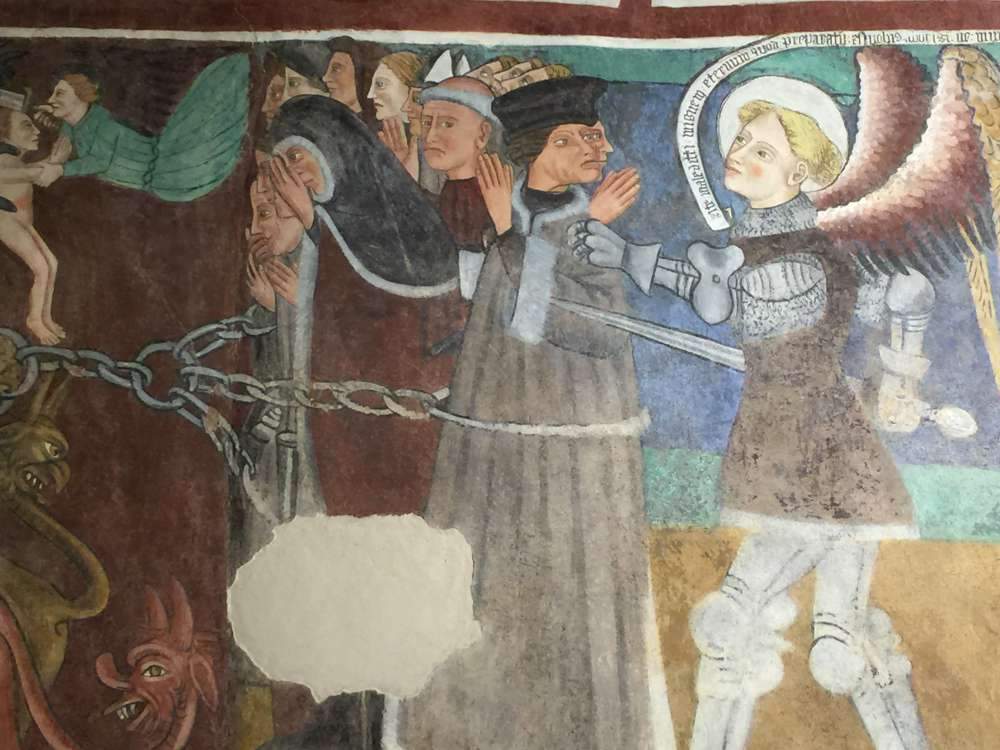

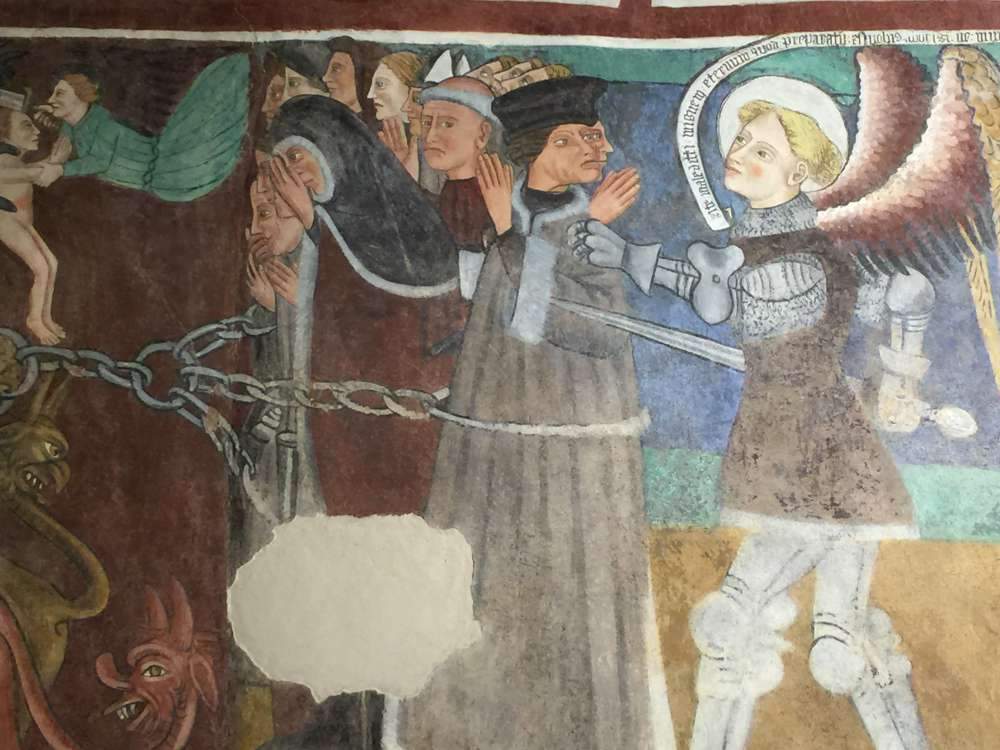

In the village of Marseiller, above a rocky promontory near the village, there is a splendid frescoed chapel, erected in the first half of the 15th century by the notary John Saluard, castellan of Cly, and consecrated on May 4, 1441. The chapel was entirely frescoed by Giacomino d’Ivrea, called by Saluard himself: the cycle, which is easy to read, presents the faithful with some typical times of the Christian religion, such as the Adoration of the Magi, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Flight into Egypt, and the Last Judgment. The frescoes also include a scene with St. Michael weighing souls: next to those destined for hell are already seen a pair of devils, depicted as monstrous reptile-like beings, waiting for the souls already chained.

TheHercules with the Lion of Judas by Arturo Martini (Treviso, 1889 - Milan, 1947), dating from 1936, is one of the symbolic works of Castello Gamba in Aosta. Two traditions collide in this work: that of Greco-Roman mythology, from which the figure of Hercules, the demigod who embarked on the twelve labors enterprise, derives, and the Judeo-Christian tradition. In fact, the lion of Judah is the symbolic animal of the Hebrew tribe of Judah, alluding to strength and victory, as well as the tradition that Jacob, the father of Judah who gave initiation to the tribe of the same name, blessed his son by calling him “lion cub.” The expression “lion of Judah,” in Christianity, has also come to refer to Jesus, as he is descended from Judah. Arturo Martini’s work is a large statue, about 2.60 meters high, which depicts Hercules standing, resting on two lion’s paws, which are the only reference to the lion of Judah. In even more recent times, the lion of Judah became a symbol of Ethiopia: in fact, the kings of the African country believed they were descended from King Solomon, himself a member of the tribe of Judah. The work thus merges these traditions for a purely political fact: in 1935, the year before the work was created, Fascist Italy had won the war against Ethiopia, and Arturo Martini’s imperious Hercules thus became a symbol of Italy subduing the Ethiopian lion.

Arturo

ArturoIn the 1980s, Aligi Sassu, one of the most important Italian artists of the second half of the 20th century, created several versions of the work Pasiphae and the Minotaur, inspired by the famous Greek myth of the half-man, half-bull creature. The story goes that the god of the sea, Poseidon, had sent Minos, king of Crete, a bull to be sacrificed in his honor. However, Minos felt that the animal was too beautiful to be sacrificed, and therefore decided to use another one instead of the one sent by the god. Poseidon, in order to punish Minos, made his wife Pasiphae fall in love with the bull: the woman became possessed by the animal and from the monstrous union was born the minotaur, a violent being moved by the most animalistic instincts, to the point of going so far as to discover his mother lying naked in a countryside, according to a motif typical of ancient painting, that of the satyrs, other creatures with insatiable sexual appetites, who were often depicted discovering naked nymphs asleep.

The ibex, as is well known, is not a fantastic animal, but certainly the decorations in Sarre Castle that have to do with ibexes are something completely unusual. The Royal Castle of Sarre has medieval origins, but it was often remodeled over the centuries, and in 1869 it became the property of the Savoy family: Victor Emmanuel II himself had it enlarged and decorated, and later King Umberto I also commissioned new decorations. These include the Gallery of Trophies, a unique room whose decorations were made with hundreds of ibex horns, which, combined with paintings depicting plants and vegetables, go to create plant motifs on the walls. The history of the castle is linked to that of the Savoy hunting grounds: in ancient times the ibex was long hunted, so much so that the species even risked extinction. Today, fortunately, the ibex is no longer in this danger, so much so that in some countries hunting this animal is no longer prohibited, as opposed to Italy, where hunting ibex is still prohibited.

The Cathedral of Aosta has two splendid medieval mosaics from the 13th century: the upper mosaic presents, in the context of geometric interlacements, a singular set of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures, symbolizing geographical places and zodiac signs but also referring to biblical episodes. It is, in essence, a condensation of Christian cosmography, taking its forms from pagan cosmography, passing through, wrote scholar Raul Dal Tio, “scientific illustrations of astronomical and astrological subjects to arrive at a universe populated with biblical symbols, angelic choirs, animals and monsters taken from bestiaries to represent vices, virtues and scenarios of the Apocalypse.” The most interesting animal in the mosaic is definitely the manticore, a creature believed to have a human face, a lion’s body and a scorpion’s tail: an animal similar, therefore, to the chimera, which we see depicted alongside. The manticore is the animal that appears in the center along with another fantastic animal, the hippocampus, the bird and the fish. On the outer band, in the triangles, we see instead a lion, a unicorn, a griffin and a hyena, and finally in the four panes at the ends here are the personifications of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, a chimera and an elephant. “The multiple meanings inherent in each individual animal, the result of a migration (and subsequent assimilation) from the iconography of pagan antiquity to that of Christianity,” Dal Tio further explains, “have conditioned a fragmentary reading, however only organized by themes: christological symbols (fish, chimera, griffin, lion, hippocampus), anti-world (manticore, hyena), virtue (unicorn, elephant).”

Near Aosta, in the district of Saint-Martin-de-Corléans, is one of the most interesting megalithic areas in Europe: it was discovered in 1969 and preserves several megalithic monuments, or large stones that were raised by prehistoric peoples for religious or ritual purposes. The megaliths of Saint-Martin-de-Corléans belong to at least five structural phases ranging from the Recent Neolithic (late 5th millennium B.C.) to the Bronze Age (2nd millennium B.C.) passing through the entire Copper Age (4th-3rd millennium B.C.). The Saint-Martin-de-Corléans area has been identified as a sacred area intended for worship and burial, a role it assumed especially from the last centuries of the 3rd millennium BCE, becoming one of the most important necropolises in the area. The megalithic area of Saint-Martin-de-Corléans has since been musealized and, via a walkway, it is possible to tour the area, in an itinerary marked out in six sections that follow the periodization of the archaeological site.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Aosta Valley |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.