In the biography dedicated to Virgil (Andes, 70 BC - Brindisi, 19 BC), the rhetorician Aelius Donatus describes the Latin poet as being “of large build and height, of swarthy complexion and rough features”: this is the most extensive biography of Publius Virgilius Maron extant today, dating from the fourth century AD. The noted fourth-century grammarian, who also authored a now-lost commentary on Virgil’s work, probably relied on the historical-literary compilation De viris illustribus by Suetonius (c. 69 A.D.-c. 126 A.D.), dated to the second century A.D., the veracity of which was attested by data from Virgil’s own circle. Throughout the history of art, the famous Latin poet has been depicted on a variety of occasions in both painting and sculpture, sometimes following the description provided by actual reports of his appearance, other times representing him in an idealized portrait by the artist. We have chosen here to review some of the works that feature the Mantuan author as their subject, created in different artistic periods, dwelling in particular on the pictorial arts. As already stated, in fact, Virgil appears with very different features from one another: from the oldest testimony that has come down to us so far, dating back to the 3rd century AD (which, although not a painting, we thought it appropriate to mention), to 14th-century art, and then on to the Renaissance, 17th-century art, and finally to a work belonging to Neoclassicism.

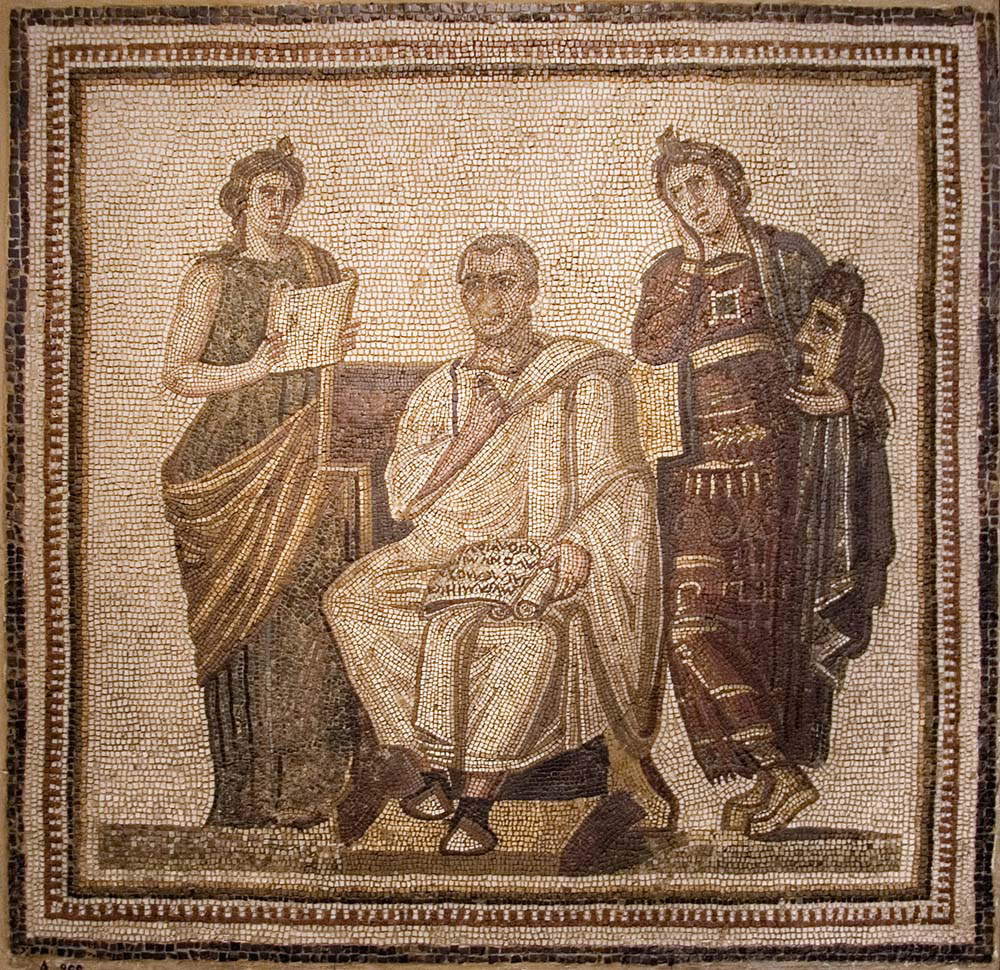

Of a period close to the description of Suetonius and Donatus is the mosaic discovered in 1896 in ProconsularAfrica, in the ruins of a Roman house known as Maison de l’Arsenal, now preserved in the Bardo Museum in Tunis: a very significant and important work because it is the only evidence from ancient times of the poet’s individualized features, even if approximate. The mansion was also decorated with other mosaics depicting the stories of Aeneas and Dido, protagonists of theAeneid.

Virgil is here seated in a chair in the center of the scene; he wears a light wool contabulata toga, which is useful for the same dating of the mosaic, since this type of toga was typical of the late empire and was characterized by its front flap transversely encircling the chest of the man wearing it. He has his gaze fixed in the void, meditating or concentrated perhaps on uttering the words written on the scroll he holds on his knees. Words that invoke the muse, summoned to help in poetic inspiration: indeed, on the scroll are verses from the proem of his Aeneid “Musa mihi causas memora, quo nomine laeso, quidve”: the interrupted verse emphasizes more the fact that the poet is trying to complete it, and for this reason he appears brooding while invoking the muse. The facial features are rough, with pronounced cheekbones and a dark complexion; the eyebrows and eyes are marked, while the nose is damaged. Standing on either side of the poet are two muses, each defined with clothing and attitude different from each other.

The muse who stands to the left of the viewer wears a green dress with darker stripes down to the ground and sleeveless, and around her hips and left shoulder is a cloak with almost amber tones. On her head is a feather, an attribute of the muses, probably a symbol of victory over the Sirens in song. In her hands she holds an open scroll and appears to be in the act of uttering words, with her gaze turned toward the poet and her mouth half-open. She has thus been identified with Calliope, muse of epic poetry. With a more relaxed attitude than the latter, who appears somewhat tense, the muse on the right is depicted: she holds her elbow against the back of the seat and with her hand holds her face with a distracted gaze; her right leg is crossed over her left. She wears a red dress decorated with gold motifs and a green cloak that falls from her shoulder, while on her feet are noted the coturni, a kind of thick-soled sandals typical of tragic actors. On her head is the feather of the muses, and in her left hand she clutches a large tragic mask: she is in fact Melpomene, muse of tragic poetry. The unusual presence of two muses next to a poet, who is usually accompanied by only one, probably refers to the fact that in theAeneid, a famous poem composed by Virgil in the last years of his life, from 29 to 19 BCE, epic poetry and dramatic poetry coexist. In the mosaic, therefore, they do not represent the classical muses invoked by a poet, but are personifications of the union existing in the poem.

|

| Anonymous mosaicist from Proconsular Africa, Virgil in chair between two muses (early 3rd century AD; floor mosaic, 122 x 122 cm; Tunis, National Museum of Bardo) |

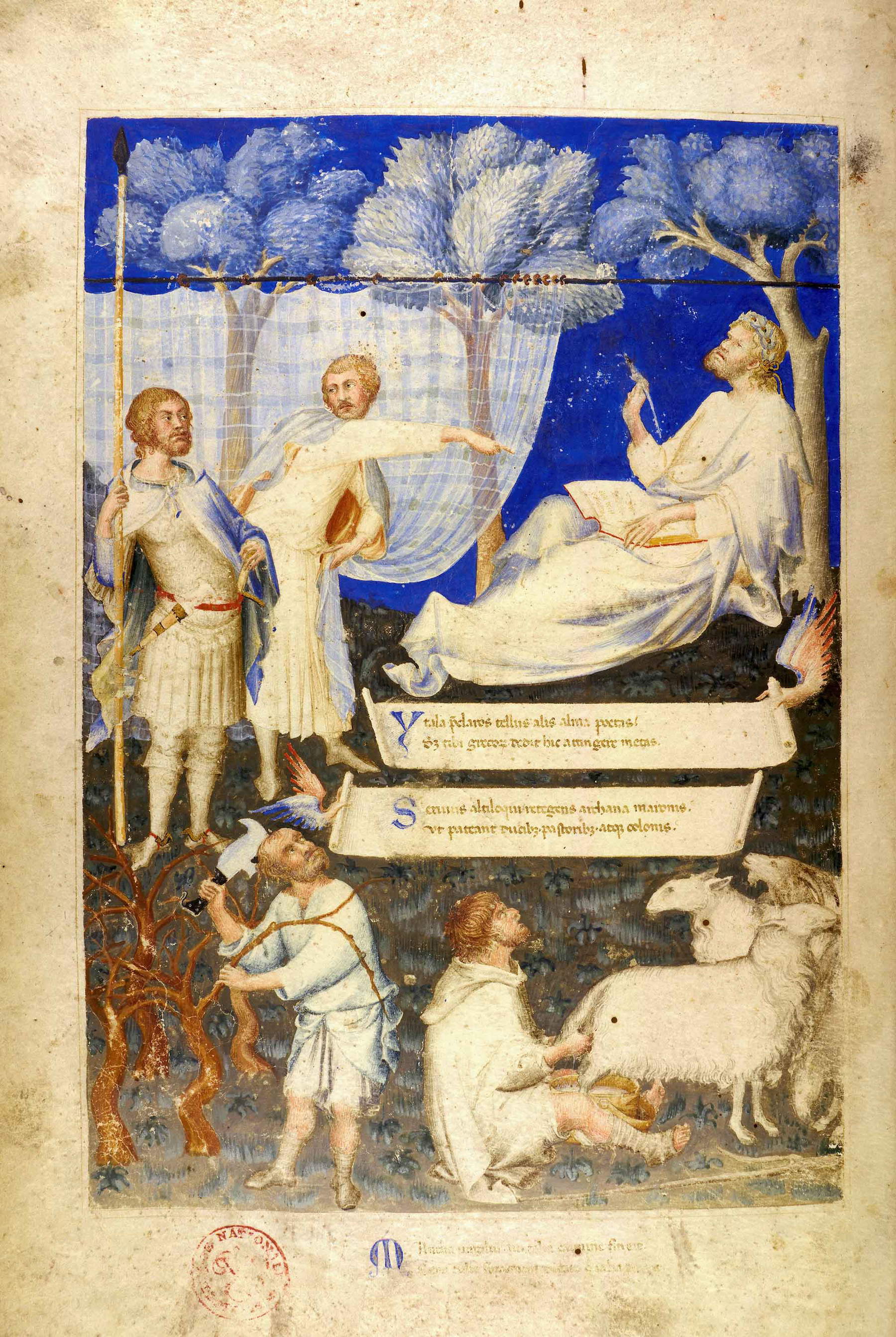

Totally different from the portrait of Virgil in the above work is the one that appears in the so-called Virgilio Ambrosiano, painted by Simone Martini (Siena, 1284 - Avignon, 1344) between 1338 and 1343. It is a miniature that serves as the frontispiece to Servio’s Commentary on Virgil, a manuscript that Francesco Petrarch (Arezzo, 1304 - Arquà, 1374) owned in his personal library. In Avignon, Petrarch commissioned from the Sienese artist contemporary with him thisilluminated work that was intended to summarize the entire contents of the codex throughallegory. In a natural landscape, the Mantuan poet is depicted lying at the foot of a tree while composing verses on his book open on his lap: he is looking upward in a pensive attitude; with his right hand, barely raised, he holds a calamus, as a sign of inspiration. He wears a long white robe and his appearance is idealized: he has wavy blond hair on which a laurel wreath is placed and is represented with a beard, unlike the Virgil of the Tunis mosaic.

The author is revealed by the commentator Servius, moving a transparent curtain, and at the same time the latter points Virgil to an armed figure, personification of theAeneid. In the lower part of the illuminated page, two other figures are noted: a figure with a billhook who is cutting branches of plants and a shepherd who is sitting and milking a goat; the former is personification of the Georgics, a Virgilian poem predating theAeneid devoted toagriculture, while the latter personifies the Bucolics, the writer’s first work devoted to the archaic pastoral world. Two cartouches between the reclining poet and the personifications of the Georgics and the Bucolics show Latin verses composed by Petrarch in praise of the poet and his commentator. To accompany this allegorical page, Petrarch added a third couplet that reads “Mantua Virgilium, qui talia carmine finxit / Sena tulit Symonem, digito qui talia pinxit,” in homage to Virgil’s poetry and Simone Martini’s art.

|

| Simone Martini, Virgilian Allegory, Frontispiece of Servio’s Commentary on Virgil (1340; tempera and watercolor on parchment, 20 x 29.5 cm; Milan, Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana) |

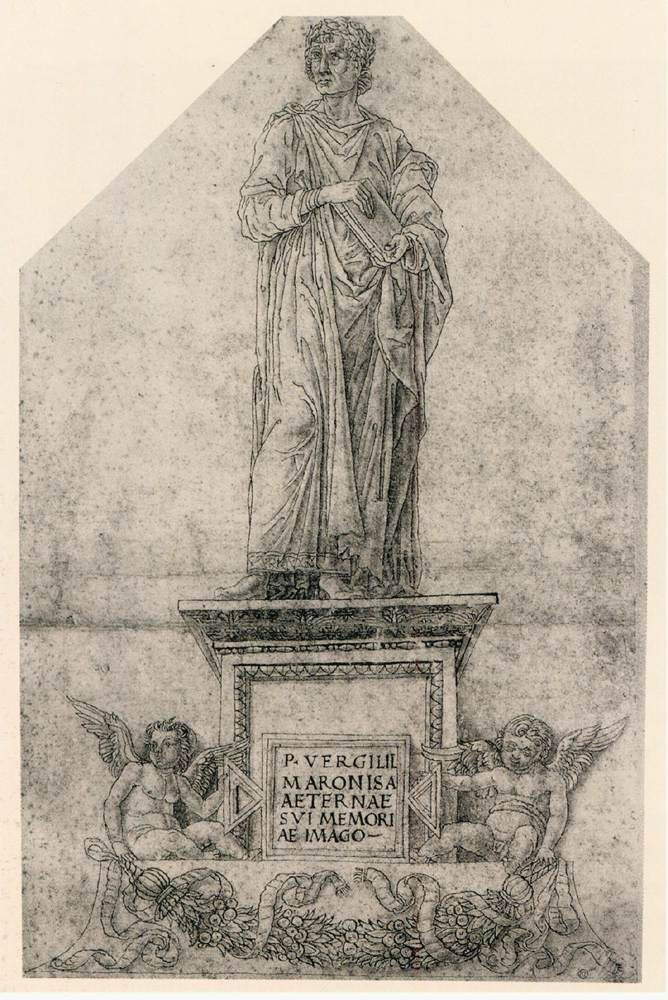

As can be well imagined, interest in Virgil and his work knew a wide spread in Renaissance Mantua : in the exhibition catalog Virgil. Faces and Images of the Poet, held in 2011 at Palazzo Te, curator Vincenzo Farinella identified a tragic event, the legendary destruction of a statue of Virgil during the events that followed the Battle of Governolo in 1397, as the cue that led the humanists working in Mantua to imagine having a great monument dedicated to the poet built: the idea was suggested by Leon Battista Alberti and Platina to Ludovico Gonzaga in 1460, and later resulted in a Mantuan design (a drawing of it is preserved in the Louvre today: we have talked about all this here on Finestre sull’Arte in an article devoted both to the monument and to the events that led to its conception) for a monument strongly desired by Isabella d’Este (Ferrara, 1474 - Mantua, 1539), which, however, did not find concretization. Add then that Isabella’s husband, Francesco II Gonzaga (Mantua, 1466 - 1519), nurtured a strong passion for Virgil, so much so that he had the rooms of a Gonzaga residence, the so-called Corte di Pietole or Virgiliana, decorated with scenes dedicated to the poet’s life, and the importance of the Virgilian revival in late 15th-early 16th-century Mantua will become even clearer. The fame of the Pietole cycle was such that the secretary of Emperor Charles V and vice-chancellor of Aragon, Miguel Mai (Barcelona?, c. 1480 - 1546), after admiring the frescoes during a visit to Mantua perhaps in 1532, asked that copies be sent to him, copies of which Giulio Romano (Giulio Pippi de’ Jannuzzi, Rome, c. 1499 - Mantua, 1546) would later take charge.

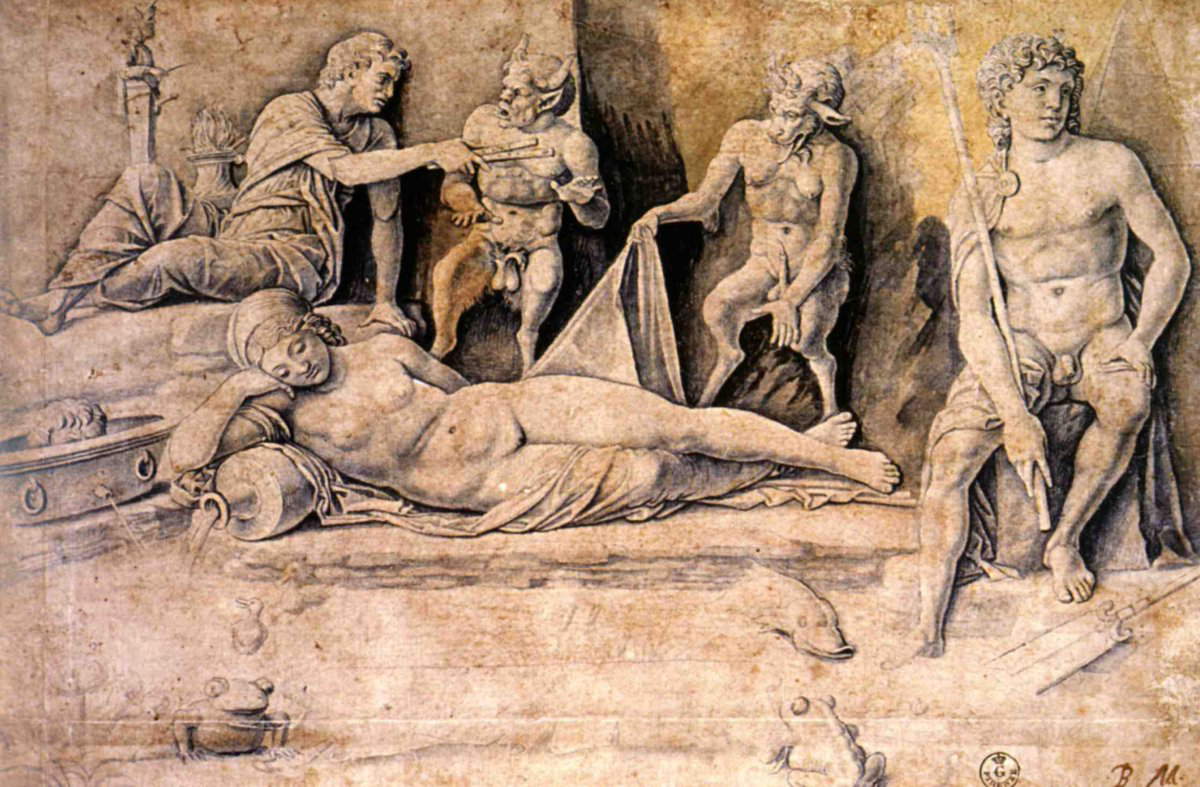

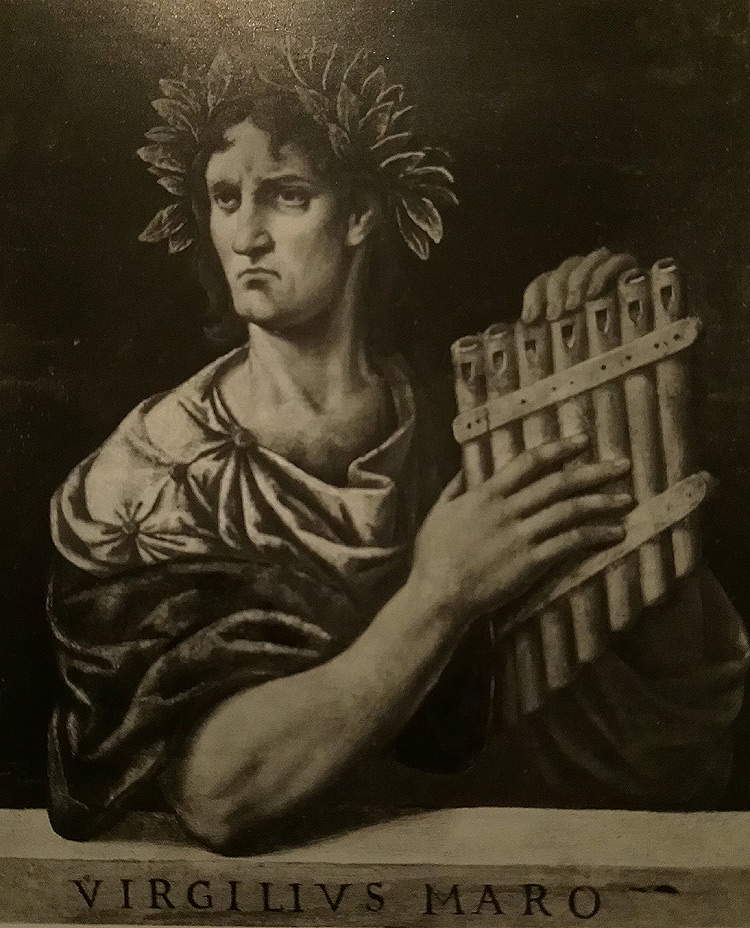

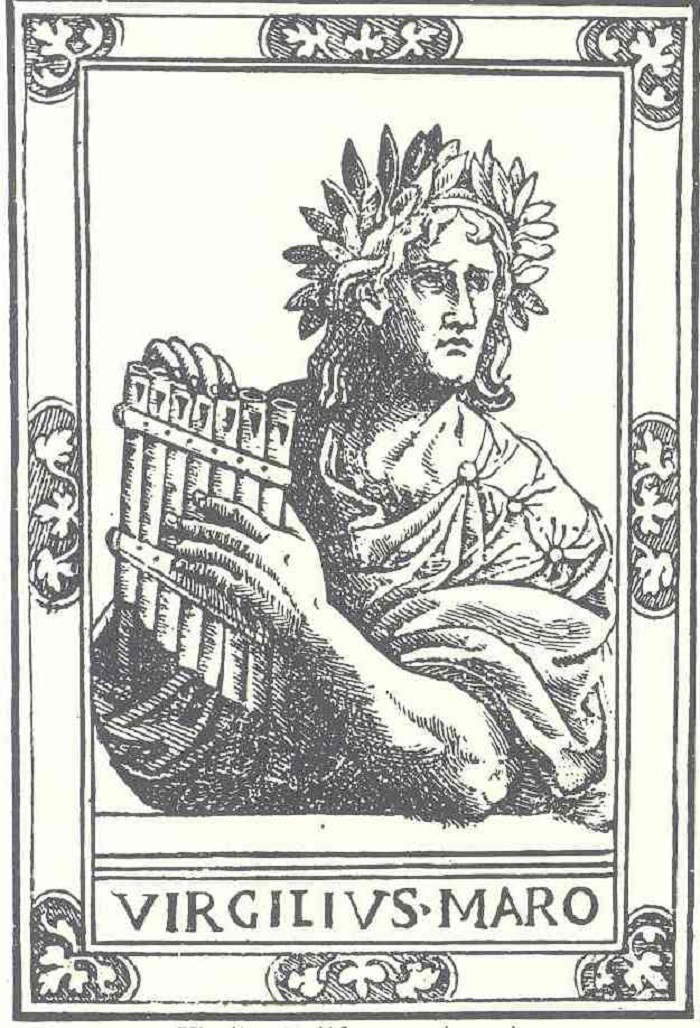

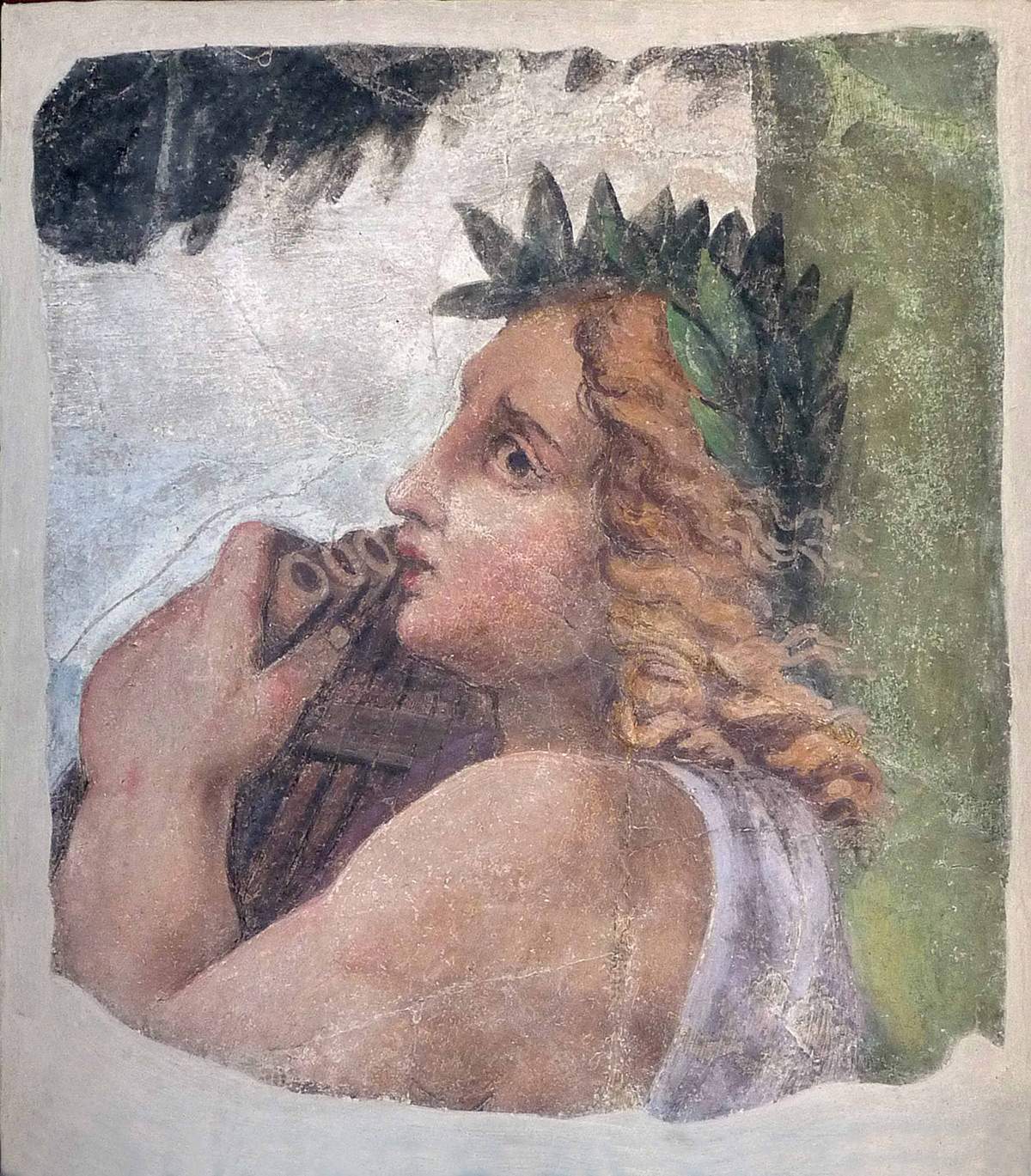

Giulio Romano himself was one of the protagonists of the revival: his is the decoration of what Farinella calls “the most Virgilian environment in Mantua,” namely, the Loggia delle Muse in Palazzo Te, created before 1530. In this environment, Farinella explained, we witness the double celebration of the patron, Federico II Gonzaga, and of culture, “in a horizon that is both Mantuan and Gonzaga-like”: here, in fact, “the marquis of Mantua, probably likened to Apollo, is the patron who allows culture (artistic, literary, musical and scientific) to spread liberally in the Gonzaga territory.” And the conduit of this spread is Virgil himself: in an image dense with classical references but which also finds echoes in Renaissance art (in particular in a drawing from Mantegna’s workshop, now preserved in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe at the Uffizi, where we see a nymph pouring water from anamphora, in the context of an allegorical scene whose meaning is not yet fully clarified), the poet is depicted as an allegorical fountain that makes the water of wisdom flow over the entire Mantuan territory (we see his laureate head protruding into a fountain). And also in the circle of Giulio Romano, a new iconography of Virgil was invented, showing him as young, handsome, crowned with laurel, and holding the flute of Pan (in reference to his pastoral compositions, the Eglogues and the Bucolics): a prototype is preserved in a painting preserved in Poland, in Wavel Castle (it would later be replicated, beginning with an image that appears in the third edition of theAeneid translated by Tommaso Cambiatore, published in Venice in 1532). The invention is then echoed in the episode with Augustus and the Sibyl invented around 1540 by Giulio Romano (a drawing of it is preserved in Munich, but its destination is unknown), where Virgil, again with laurel and syrinx, witnesses the scene: a fragment of a lost fresco (perhaps originally decorating a Gonzaga palace) is preserved, however, probably executed by Rinaldo Mantovano (Mantua, active between 1527 and 1539), recognized in 2011 by Stefano L’Occaso, according to whom this fragment was probably kept out of respect for the poet (the work is now kept at the Museo della Città in Palazzo di San Sebastiano in Mantua).

|

| Andrea Mantegna’s circle, Project for monument to Virgil (c. 1499; drawing, 340 x 220 mm; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des dessins; inv. RF 439) |

|

| Giulio Romano, Eastern Lunette of the Loggia delle Muse (before 1530; fresco; Mantua, Palazzo Te) |

|

| Bottega di Andrea Mantegna, Mythological Scene (ca. 1500; pen and blue ink, blue and black watercolors, yellowed white paper, 264 x 398 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Giulio Romano’s circle, Portrait of Virgil with syrinx (c. 1524-1532; Krakow, Wavel Castle) |

|

|

| Rinaldo Mantovano (?), Virgil with the syrinx (c. 1540; torn fresco 55 x 48 cm mounted on 62.2 x 52.8 cm panel; Mantua, Museo della Città in Palazzo di San Sebastiano) |

Continuing with the pictorial portraits of Virgil in art history, let us mention another famous work, also from the 16th century, where the poet is depicted in a more complex and crowded scene, surrounded by a multitude of characters. We are talking about Raphael ’s Parnassus (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520), a magnificent fresco that can be admired in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican Museums, completed between 1510 and 1511 on commission by Julius II della Rovere.

Raphael’s great fresco consists of a depiction of Mount Parnassus, in the center of which sits, looking skyward and with his head crowned with laurel, the god Apollo, as he is playing the lyre from his arm.

Around him are placed, some standing and some seated, the nine Muses, the patrons of the arts, and ancient and modern poets. Among them are recognizable side by side Dante (Florence, 1265 - Ravenna, 1321), Homer and Virgil, placed to the left in the upper part of the fresco. The trio of supreme poets appears well-characterized: Homer, the older, stands out in front of the other two, to emphasize their greater importance; to his right, in profile, is Dante, while the young Virgil is depicted with a three-quarter face, as he is pointing to the god Apollo while addressing Dante. Virgil’s appearance is still very different from what the ancient biographers described; he is a newly idealized portrait: he has a fair complexion, light brown curly hair, and his features are anything but rough. Here Virgil plays the role of guide to Dante, leading him to the source of inspiration of the mythical deity with the lyre, god of music and all the arts.

|

| Raphael, The Parnassus (1510-1511; fresco, base 670 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Stanza della Segnatura) |

|

| Raphael, The Parnassus, detail |

Virgil is depicted in the company of Dante in the painting Dante and Virgil pass through the gate of Hell created by Rutilio Manetti (Siena, 1571 - 1639) between 1629 and 1632 and housed in the Pinacoteca di Siena. The author of theAeneid is described by Alighieri as “de li altri poeti onore e lume” (of the other poets honor and light) at the moment of their meeting in Canto I of Dante’s Inferno, and, in equal fashion to Raphael’s Parnassus, the Mantuan poet guides Dante, this time through the circles of Hell, acquainting him with all aspects of the world of the afterlife and giving him comfort. Arriving before the infernal gate on which stands the famous phrase “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate,” Dante is almost frightened. “E poi che la sua mano a la mia puose / con lieto volto, ond’io mi confortai, / mi mise dentro a le segrete cose”: it is precisely this triplet that inspired Manetti’s painting. Against the backdrop of a forest, Dante and Virgil pass through the great stone gate of Hell at the center of the composition; the scene is illuminated only by the light coming from outside the gate, from the forest. Virgil advances gracefully and confidently through the stone gateway, clad in robes typical of antiquity; even his face recalls ancient sculptural portraiture. Dante, on the other hand, advances in an insecure, doubtful manner, but what is well highlighted in the painting is the sentimental pathos, the strong emotional participation expressed by the mutual glances and the shaking of hands, a significant element that refers to the triplet of the Comedy.

To conclude this brief excursus on the pictorial portraits of Virgil through the history of art, we thought of analyzing a painting belonging to Neoclassicism, made by one of the greatest interpreters of the movement: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Montauban, 1780 - Paris, 1867).

|

| Rutilio Manetti, Dante and Virgil Cross the Gate of Hell (c. 1629-1632; oil on canvas, 278 x 218 cm; Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Tu Marcellus Eris (1811; oil on canvas, 326 x 307 cm; Toulouse, Musée des Augustins) |

The artist completed this painting in 1812, choosing to depict the reading of one of the most poignant passages in theAeneid: in the sixth book of the Virgilian poem, Aeneas arrives in the Elysian Fields, the place where the blessed dwelled; here he meets his father Anchises, who accompanies him to explore these lands, while describing to his son many leading figures in republican history. Among them, he shows him the young Marcellus, grandson of Augustus and son of Octavia, the emperor’s sister. The young man had died prematurely at only nineteen years of age, in 23 B.C., and Anchises in his description, after recounting the weeping and despair due to the terrible misfortune, says, “Heu, miserande puer, si qua fata aspera rumpas, tu Marcellus eris” (Oh alas , child worthy of pity, if you can somehow force the cruel fate, you will be a worthy Marcellus!).

In his painting, Ingres thus depicts the theme of Tu Marcellus eris by depicting Virgil standing, crowned with laurel, reading the above passage in front of Augustus, Livia, Octavia, Agrippa, and Maecenas: in a room of the emperor’s residence, in fact, Augustus and Livia, his second wife, sit in the center of the scene (the latter is, by the way, the only figure in the painting with her gaze turned toward the viewer), and in their midst Octavia, mother of the young Marcellus, is completely unconscious, with her head on her brother’s lap. Agrippa and Maecenas watch the scene from the right edge of the painting, while the poet, illuminated by the candle burning high near him, is facing all the characters. The reading of the passage from theAeneid is so touching and still painful for Octavia that it causes the latter to faint, and her brother, with his right hand, makes the gesture of interrupting the reading. Once again, Virgil’s features are not compatible with the biographers’ description of a “brown complexion and rough features”: Ingres shows Virgil as a young man with a refined appearance and light, delicate features, and sensitive in spirit.

The painting was commissioned from the artist by Sextius-Alexandre-François Miollis, French governor of Rome from 1808 to 1814 and promoter of celebrations in honor of Virgil, for his residence at Villa Aldobrandini. The work is now housed at the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse.

These are just some of the works that refer to the Latin poet: in fact, art history has dedicated numerous masterpieces to him, either depicting him on canvas or narrating scenes from his famous poems. From ancient art to contemporary art Virgil has been a source of inspiration, a famous figure who will be remembered and loved for eternity.

Bibliography

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.