His untimely death did not prevent painter Giuseppe De Nittis from ploughing the skies of southern Italy in his early days, nor from later shining in the two capitals of art: London and especially Paris.

Despite his short career, his painting, which some insist on calling only “Impressionist” (although, it is true, from that current he picked up the lesson on atmospheric research and interest in the themes of modern life), was so intense that in a few years he traced everything that was happening in Europe.

Far beyond, then, the repercussions of the Franco-Prussian postwar period and the phenomenon of industrialization: a condition, this, from the “Belle Époque,” which, between the revolution of photography and the novelties of Japanism, allowed him to pour beauty, but also lyricism and realism, into poignant paintings and pastels, and especially into those “frescoes of life” depicting the beautiful divines of the Parisian salons.

It is this mixed atmosphere of novelty and fascination, of ferment and speed, where representatives of the well-to-do circles of the “modern city” move, the noblewomen entertaining cenacles in their elegant circles, and where the landscapes of the new urban world of the late 19th century also stand out, that we find again until April 13 in Ferrara at the exhibition De Nittis and the Revolution of the Gaze. Layout by Maria Luisa Pacelli, Barbara Guidi and Hélène Pinet, the exhibition traces the fascinating adventure of a painter who, like other artists, although he trained essentially in Italy and briefly attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, would find greater fortune outside our borders.

Room after room, gliding with mellifluous steps through the ancient Renaissance spaces of the Palazzo dei Diamanti, the exhibition highlights how much the multiple evolutions and stages De Nittis went through to establish himself and win success, immediately represented a sure rise for his artistic vicissitude, which concerned both the critics of the time and the art market. With his way of translating the immediacy of reality on canvas he succeeded, like few others in those years (a comparison is possible only with Boldini and Tissot), to fascinate, tracing landscapes, portraits or crowded streets with the sound of a brush. And to collect commissions and credibility. His refined lens is pointed in the direction of modernity, an address that, leaving a trace in a nourishing series of fleeting snapshots, remarked on the vibrancy of that teeming urban world, obscuring or, if nothing else, overshadowing the already obvious and ominous signs of the two industrial revolutions.

Stealing his eyes from the early experimentation of photography, as is evident in the glancing relationships with Alfred Stieglitz, Giorgio Sommer or Gustav Le Gray, De Nittis was able to translate a fast-paced reality through absolutely daring framing with unexpected cuts as in Léontine in a dinghy and unusual perspectives that on closer inspection still surprise the observer today.

Fundamental to his consecration as a European painter was crossing the Alps, although here in Italy, among coruscating skies and profiles of mountains and plains, among sea horizon lines, De Nittis inaugurated his unprecedented look at reality. It was here, and especially in the South, that he sharpened his vision to light up, and it was always here that the desire to paint began to mount, and the passion to grow artistically and make himself known pressed on.

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Léontine in a dinghy (1874; oil on panel, 24 x 54 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Alfred Stieglitz, Rainy Day in Paris (1895; photogravure, 9 x 16 cm; Paris, Musée dOrsay) |

|

| Gustave Le Gray, Boat in the Moonlight (1856-57; print on albumin paper, 29.6 x 41.1 cm; Paris, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris) |

Only when he felt his ties with the dealer Goupil as intolerable, (with whom, in fact, he had signed a contract in 1872 where he ceded exclusivity on the sale), only when he felt trapped by the rules the market imposed on him, did the artist need to look elsewhere. Especially in Paris.

As soon as he hears the rumble, the echo of the din of this mecca of the arts, already from his first stay in 1867, that city envelops him and there he decides to settle. But it is mainly thanks to the model and future wife, Léontine, who introduces him to the salons of high society, that he somehow almost disavows his origins.

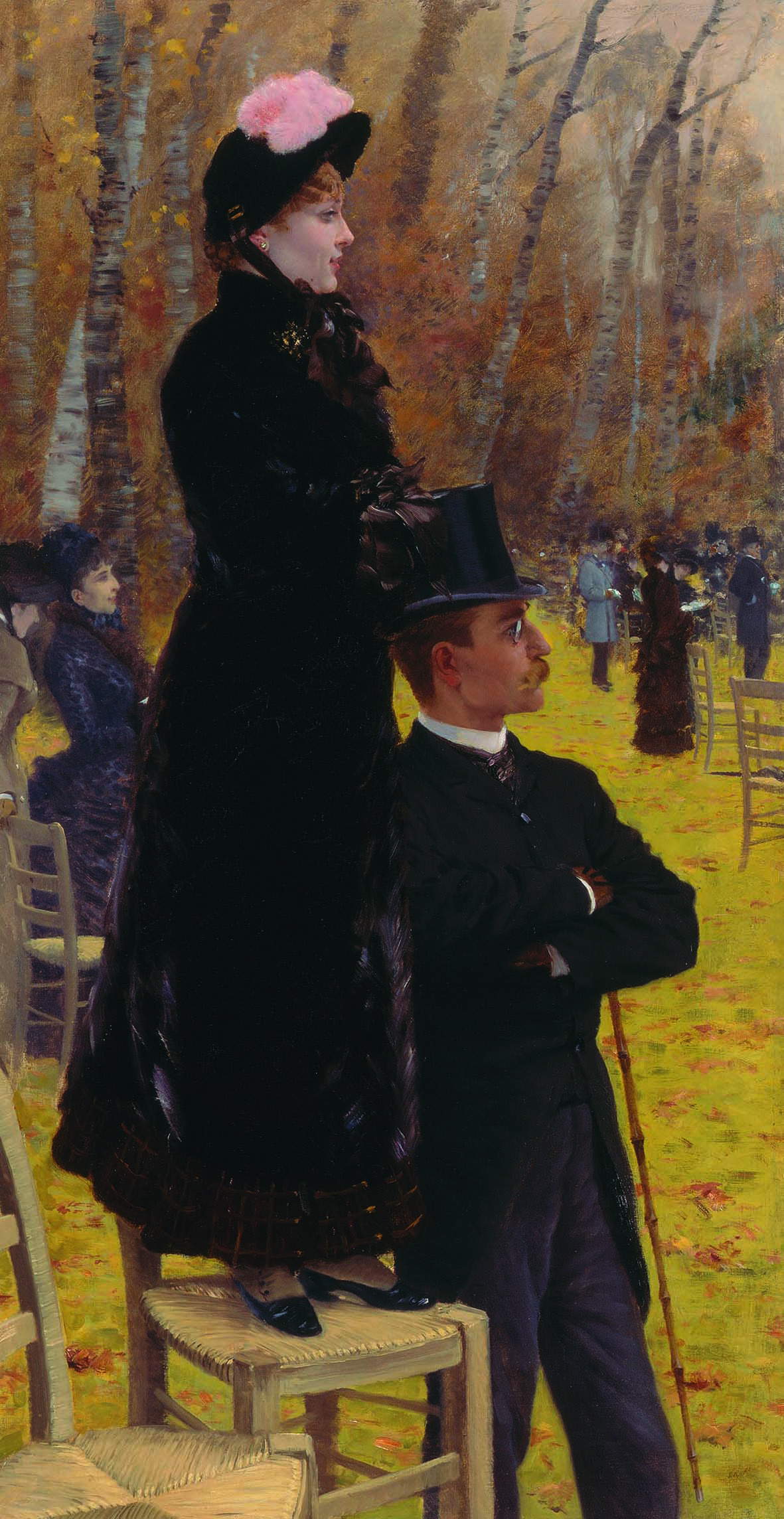

Of Paris, its cafés and boulevards, its grand avenues, he remains enchanted (see At the Races of Auteil - on the chair, or Bridge) he will in fact write to his friend Adriano Cecioni: “Life here, but how much, how interesting. He likes everything about the city: the organization, the cleanliness, ”everything here is a clock of order."

It was said of him that he was so impressed by the places, the things he saw, the novelties he experienced live, that from “Italian in Italy,” he became “a Parisian in Paris” and no less a “Londoner in London.”

De Nittis, as transpires from the Ferrara exhibition through a conspicuous selection of works mainly from the Foundation in Barletta, his hometown, was an artist who was not only able to intercept atmospheric, social, and urban and natural landscape variations and changes before others, but was distinguished by a quest, and an eagerness to see and know, that declined first in France, then among English visions (it is no accident that he favored such views as Westminster or The National Gallery and St. Martin’s Church in London). Insuppressible need to acquire that ability, which he would make all his own, to render at its best, the genus loci, and all the possible new energies of places.

Moreover, he was born with an exceptional gift that allowed him to imprint in his eyes everything he saw, what he breathed around: nuances, clues, scents... each of these “impressions” was decanted into his seductive, often enpassant canvases. In fact, we know that he used an entirely original method to do this (and perhaps that is where his “impressionist” trace consists): he had rented, then finally purchased, a fiacre, the carriage inside which he repaired to see without being seen. Drawing without incurring infractions of any kind was a certainly bizarre way of getting around the obstacle of the June 7, 1848 law against assemblages. From that carriage, a veritable mobile atelier, he recorded people, scenes and landscapes, not only at great speed, but also in the act of moving slowly. Dancourt said of him, as early as 1887, that he made works as “living photographs.” Through thus an entirely invented and original method, he painted what he saw “in an instant,” reproducing what the window framed.

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, At the Races of Auteuil On the Chair (1883; oil on canvas, 107 x 55.5 cm; Barletta, Pinacoteca Giuseppe De Nittis) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Westminster (1878; oil on canvas, 110 x 192 cm). Courtesy Marco Bertoli |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, The National Gallery and Saint Martin’s Church in London (1877; oil on canvas, 71 x 105.5 cm; Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux Arts de la Ville de Paris) |

The eccentric experiments, the dogged search for a personal style and taste, the artist sought them everywhere. A source of inspiration for him is what gravitates to the places he frequents, anything circulating in cultural circles, from Japanese prints (seen for the first time at the Universal Exhibition of 1867) or the comparison, for all artists inevitable, with the first photographic print proofs. Very attentive to this subject is his dealer of choice Goupil, who, in order to reach a wider audience, is seduced by all existing techniques of reproduction: the prestigious burin engraving, lithography, etching, black manner, aquatint, and then, from the 1950s, photography.

Photography and the aesthetics of Japanism truly constituted a concert of two voices for De Nittis. Although quite distinct from the Impressionist phenomenon, in a parallel way, the painter of Apulian origin interpreted the taste of the time by interweaving his painting with that refined Japanese syntheticism and with the innovative codes of photography.

The fashion of "japonaiseries“ claimed victims, especially in the artistic sphere, but not only. In the year de Nittis discovered Paris, 1867, the French capital hosted the first official presentation of Japan at a Universal Exhibition. From then on, a new idea of taste was introduced, in which ”a respectable atelier was furnished with refined oriental objects and the fashionable painter, dressed according to current taste, was the one who did not fail to portray a Japanese screen or lacquer in his paintings" (Manuela Moscatiello). Fashion à la japonais in De Nittis translates mainly into an expressive search for the color palette, and in the various paintings in which white, often that of snow, is the predominant color.

The aesthetics of Japonisme, is yes decorative but it is also synthetic, because it teaches how to restore the strong impression of what it was meant to depict. Japanese elements sometimes surface more strongly, sometimes more subtly as in Serene Dawn and Lake of the Four Cantons, or in other works such as By the Lake, Winter Walk, In the Snow and Léontine Skating.

However, it is Winter Day that is the ultimate. In the painting, Léontine is portrayed at home while an incredible snowfall, which occurred in Paris in 1875, can be seen through the window. On that occasion, De Nittis writes in his notebook, “Paris is all white with snow (...) for me it is a vision of Japan.” With the variations of white, De Nittis experimented with new languages, nuances, and the color palette increased. The quality of the work is also evident to Edmond de Goncourt: “the most extraordinary symphony of whites, a new way of using chalk, very far from traditional techniques.”

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Walk on Lake Lucerne (1881; oil on canvas, 61 x 91 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, By the Lake (c. 1880; oil on canvas, 73 x 52 cm; Barletta, Pinacoteca Giuseppe De Nittis) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Winter Walk (1879; oil on canvas, 131.5 x 77 cm; Barletta, Pinacoteca Giuseppe De Nittis) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Effect of Snow (c. 1880; oil on canvas, 54 x 73 cm; Barletta, Pinacoteca Giuseppe De Nittis) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Léontine skating (c. 1875; oil on panel, 55 x 37.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Winter Day (1882; pastel on canvas, 150 x 89 cm; Barletta, Pinacoteca Giuseppe De Nittis) |

The use of pastel is also closely related to japonisme, that is, the influence of Japanese art. We know that De Nittis did not modify his pastels by adding a fixative, but worked the pigment by reducing it to impasto: that is, he crumbled the pastel, mixed it with water and applied it with a brush.

“The marriage of the painter with the Japanese muse, generated beautiful creatures, full of life of movement, seductive that produce on viewers an impression of great surprise” (Renato Miracco). Being influenced by Japonisme was not, therefore, only about materials, but was also a matter of the subjects chosen and the layout of the composition.

In spite of everything, in spite of the innovations he introduced in the artistic field, the misconception still persists that De Nittis was a worldly painter, pandering to the bourgeoisie of his time, a shrewd artist who exploited the exotic fashion of his passion for Japan to sell and achieve early fame. De Nittis, on the other hand, Antonio Paolucci has written, “recounted in pictures the melodious tumult of the modern city, the gallant rendezvous at the Bois de Boulogne, the beautiful women and the socialites, the pulsating life on the boulevards, the parties of a bourgeoisie at the height of its splendor.” If he has recounted the character, modes of dress, and social habits of the elites, especially Parisian elites, it is because in the fabulous years following the great fear of the Commune, Paris needed this, it was Europe that expressed this desire. A need that De Nittis soon knows how to fill. And he is not to blame for it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.