At a quarter past eight in the morning of August 8, 1944, a truck belonging to the Germans occupying Milan was the target of an attack that, according to the records of the Republican National Guard, did not result in any casualties among the Nazi soldiers, but cost the lives of six Milanese citizens and the wounding of eleven others. It was never determined who the perpetrators were, and what is more, it was an anomalous attack, as historian Massimo Castoldi has reconstructed: it had hit a target that was anything but strategic, and moreover under totally unusual circumstances (such as the presence of only one German soldier on board the vehicle, which meant leaving a military vehicle practically unattended), and had not taken into account the possible involvement of the population (so much so that it only proved innocent victims).

It is not known, therefore, whether it was a sham hatched by the Nazis themselves (who in any case, noted historian Luigi Borgomaneri, did not need to implement simulations to initiate reprisals) or, perhaps more likely, some loose element that took a reckless individual initiative without considering the consequences. The fact remains that the Nazis’ reprisal was extremely harsh, for at dawn on August 10, just two days after the attack, SS Captain Theodor Saevecke ordered the Milanese fascists to then take partisans from San Vittore prison and have them shot in Piazzale Loreto. The shooting was carried out by a platoon of fascist soldiers from the Ettore Muti Legion, commanded by Captain Pasquale Cardella. The fifteen partisans were shot at six o’clock in the morning, after which their corpses were displayed in Piazzale Loreto until eight o’clock in the evening, as a warning to the population, with a sign identifying them as murderers, and with passers-by being forced to stop and observe the havoc. The youngest was twenty-one years old, the oldest fifty-two. The poet Franco Loi, then 14, had been an eyewitness at the time and would later recount, “There were many bodies thrown on the sidewalk, against the fence, a few theater posters, the Smile Gazette, signs, bandits! Bandits caught with guns in their hands! All around, the silent people, the hot sun. When I came to see them it was like a vertigo: shoes, hands, arms, dirty socks; [...] to my childish eyes it was unheard of: men thrown on the sidewalk like garbage and other men, young men dressed in black, who seemed to be standing guard armed!”

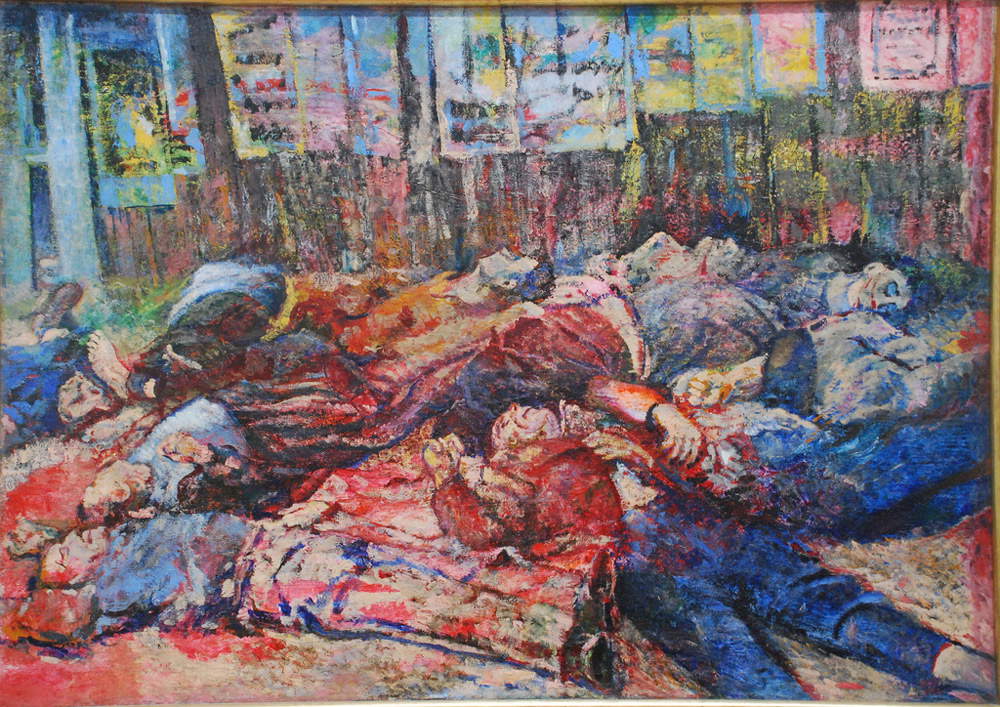

This “vertigo” is the subject of one of the most famous paintings of the Resistance, I martiri di piazzale Loreto by Aligi Sassu (Milan, 1912 - Pollença, 2000), a work executed shortly after the massacre, later exhibited at the 1952 Venice Biennial (under the title Civil War, earning, moreover, numerous appreciations) and immediately purchased by the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome at the suggestion of art critic and historian Giulio Carlo Argan, for the sum of 309.300 liras, corresponding to about 6,000 euros today. The work is still in the Roman museum. The painting, based on a well-known photograph of the massacre, shows the bodies of partisans lying on the ground, covered in blood, symbolizing the victims of Nazi oppression. Sassu, a fervent anti-fascist who was imprisoned in 1937 for his militancy (he would remain in jail for about a year: in July 1938 he was later pardoned by the king), decides to interpret the photograph with a composition of charged and vibrant tones, using strong colors and bright contrasts to convey to the viewer the intensity and tragedy of the event. The result is therefore a work capable of communicating a dense emotional and political charge, aimed at highlighting the sacrifice of those who fought against the Nazi occupation and at the same time remembering those who lost their lives in the fight for freedom. Red tones predominate, the color symbolizing the blood shed by partisans, Sassu’s political faith and also his art.

Sassu later recounted that he went directly to the scene to observe what the republicans, under orders from the Nazis, had done. “It was on the strength of the anguished confidence of a friend,” Sassu would later say, “that I went there, to the site of the massacre: ’Aligi, they have made a massacre and the corpses are still in the square.’ So I found myself with a heart swollen with horror and emotion, powerless among powerless people, a petrified spectator of the ludibrium to which the republican militiamen had subjected the bodies of those generous brothers of ours. I returned distraught; having arrived at the house on Via Bagutta I immediately wanted to fix on canvas the memory of that sacrifice, I immediately wanted to celebrate in painting what I had seen. But I did not have a canvas and for so many reasons I could not have procured one on the spot. So I began to paint over another painting of mine depicting a cyclist. After two days of work I finished I martiri di piazzale Loreto, a work that became among the most representative and the best known of that period; a work purchased by Argan for the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Rome. I have already said, those scenes had shocked me. Yet there was in me, in the fire that stirred me as I painted, in the anxiety that filled my chest as I tried to express what I had seen, an immense sadness. I thought, in the end, that from those bloody and inert bodies there arose a silent admonition for all Italians and, indeed, for all men: not of revenge or of rancorous pursuit of wrongs and reasons, but of peace, of just peace.”

In reality, we do not know to what extent Sassu’s account is reliable, since it is difficult to imagine that immediately after August 10 photographs of the massacre were already circulating: even, according to historian Sergio Luzzatto, the dating of the work, whose source is solely the artist’s testimony (also because, as the above-mentioned Castoldi noted, painting a’cumbersome two-by-one-and-a-half-meter canvas would have exposed the artist to enormous risks, since, if found during an inspection by a Fascist or Nazi, “it would have meant in those months immediate arrest, and perhaps shooting or deportation”). Castoldi pointed out, however, that in December of that year the photograph that inspired the artist was used for a flyer that was hung at the Falck steel mills in December 1944. The first attestation of the work, on the other hand, dates back to 1951, when it was first mentioned in the newspaper Milano Sera, which published a statement by Sassu, in which the artist reported that he had painted The Martyrs of Piazzale Loreto “in August 1944, immediately after having seen the ridicule that the republican rogue made of the bodies of our brothers. Yet there was in me, in the fire and anxiety that stirred me, in trying to express what I had seen, a great peace and not hatred, but an immense sadness. From those bleeding and inert bodies arose an admonition and a warning to all men. Peace.”

Whatever the actual date of the work’s creation, I martiri di piazzale Loreto remains one of the best known and most celebrated visual texts of the Resistance, as well as “one of Aligi Sassu’s most moving masterpieces,” as Mario De Micheli had written. The choice to depict the massacre of the partisans is meant to be not only a way to convey the memory of the tragic event, as well as a kind of personal tribute by Aligi Sassu to the victims of the massacre and an exhortation against the atrocities of oppression and tyranny. Sassu, with his painting, operated a true reversal of the intentions of the fascists, who would later have the photo from which the work is taken circulated, again as a warning to the population. What was a threat becomes a testimony. The icy air of the photograph is ignited with a painting of flaky tones, which transfigures the documentary image of a massacre into a commemoration that, while not departing from the photo and while not losing accents of realism, through a dense expressionism charges the source image with an entirely opposite meaning. The grim intimidating message thus becomes a heartfelt elegy, straddling the need for fidelity to historical fact and the need to construct a myth.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.