by Francesca Interguglielmi, published on 15/04/2021

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

In the late 15th century, Sandro Botticelli made several drawings to illustrate Dante's Divine Comedy. They are among the lesser-known works of the great Florentine artist but they restore to us all his visionary power.

Between the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin and the Vatican Library are 92 drawings illustrating a manuscript text of the Commedia by Dante Alighieri (Florence, 1265 - Ravenna, 1321). These drawings were commissioned from Sandro Botticelli (Florence, 1445 - 1510) by Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici (Florence, 1463 - 1503), cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent. This member of the Medici family is also credited with owning some of the Florentine painter’s best-known works: the Primavera, the Birth of Venus and Pallas and the Centaur. Compared to the mythological-themed works just mentioned, which have become among the universal symbols of Italian Renaissance painting, the Commedia drawings have often remained in the shadows within Botticelli’s output. In 1632, in fact, the manuscript appears to have already been dismembered. The seven folios currently housed in the Vatican Library. They arrived in Rome with the library of Christina of Sweden: they were previously purchased on her behalf in 1650 by her librarian, Isaac Vossius. Upon the queen’s death, they passed to Cardinal Pompeo Azzolini and were later bought by the future Pope Alexander VIII. Regarding the 85 Berlin drawings, we know that in 1803 they were in Paris with a bookseller of Italian origin, Giovanni Claudio Molini. Before February 1819, they were purchased by Alexander Douglas, who was to become the 10th Duke of Hamilton. In 1882, it became necessary to sell the manuscripts stored at Hamilton Palace at Sotheby’s. Friedrich Lippmann, who was the director of the Royal Prints and Drawings Cabinet in Berlin, managed to blow off the public auction in order to buy time and purchase for his own institution that collection, which also included Botticelli’s Dante drawings.

Few references can be found in ancient sources regarding these drawings. In theAnonimo Gaddiano or Anonimo Magliabechiano (Magliabechiano Codex XVII, National Library of Florence) we find the following indication: “He painted and storied a Dante in cartapecora to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, which was a marvelous thing kept.” The judgment, here decidedly positive, changes connotation in the work of Giorgio Vasari, who, referring to some of Botticelli’s Dante-themed drawings, writes thus, “Where, for being a sophistic person, he commented on a part of Dante, and figured the Inferno and put it in print, behind which he consumed much time; for which, not working, was the cause of infinite disorders to his life.” A reference is also found in Filippo Baldinucci, who basically leans on Vasari’s words. It cannot be said with certainty that Vasari was referring to these drawings; in fact, only the execution of drawings related to the first cantica,Inferno, is indicated. It is likely, therefore, that he was referring not to this series, in which all three cantica are present, but rather to the first occasion on which the Florentine painter tried his hand at depicting Dante’s text. These were the illustrations that were to accompany the 1481 edition published in Florence by Niccolò della Magna with the important commentary by Cristoforo Landino, who defended the figure of Dante as a poet in the vernacular within the neo-Platonic culture that was dominant at the time. It was the first printed Commedia in which an accompanying set of illustrations was provided. Of those illustrations, only nineteen engravings by Botticelli executed by Baccio Baldini (Florence, 1436 - 1487) remain, covering only theInferno.

|

| Baccio Baldini (based on a drawing by Sandro Botticelli), Dante threatened by the beasts is rescued by Virgil (1481; burin print; Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana) |

|

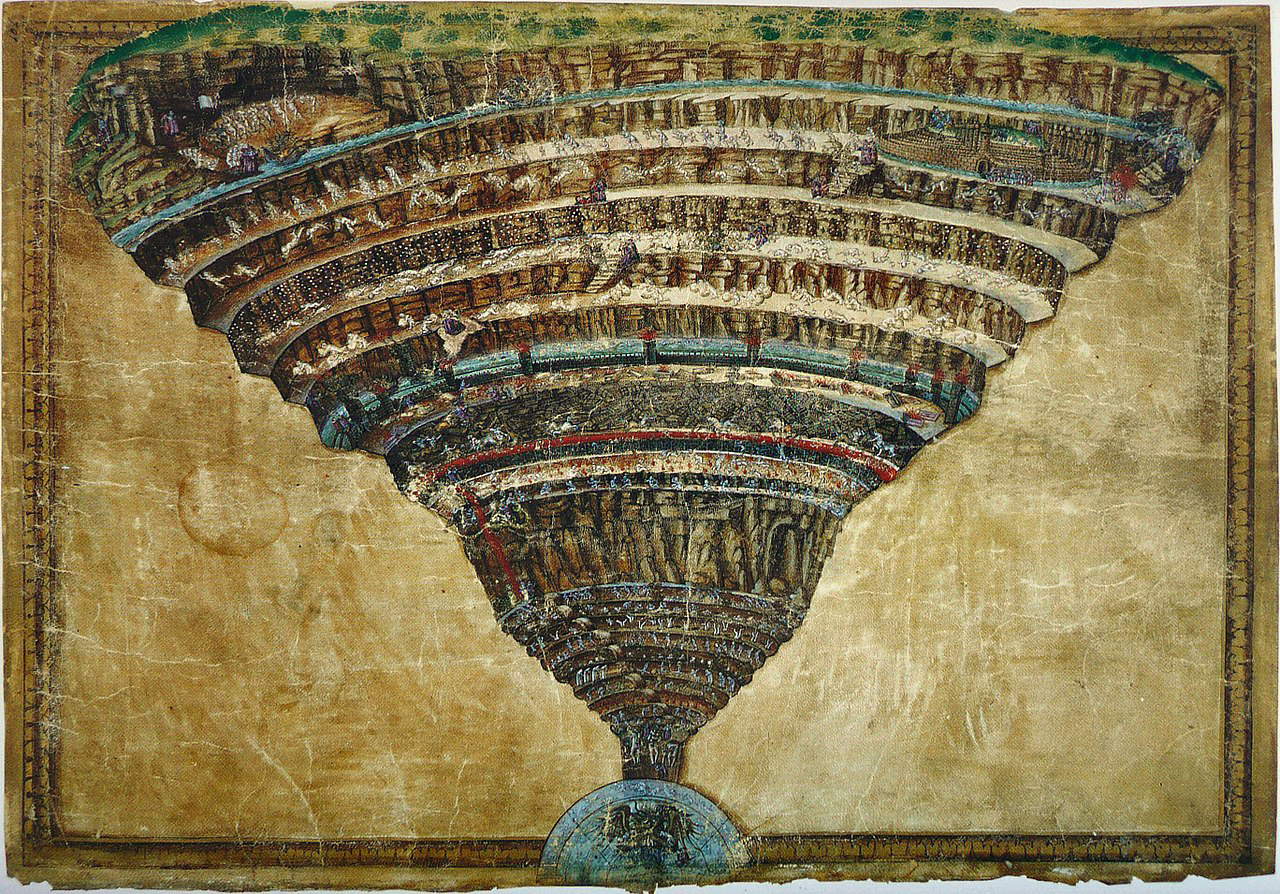

| Sandro Botticelli, The Infernal Voragine, from drawings for the Divine Comedy (c. 1481-1495; silver point and ink on parchment, 325 x 475 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

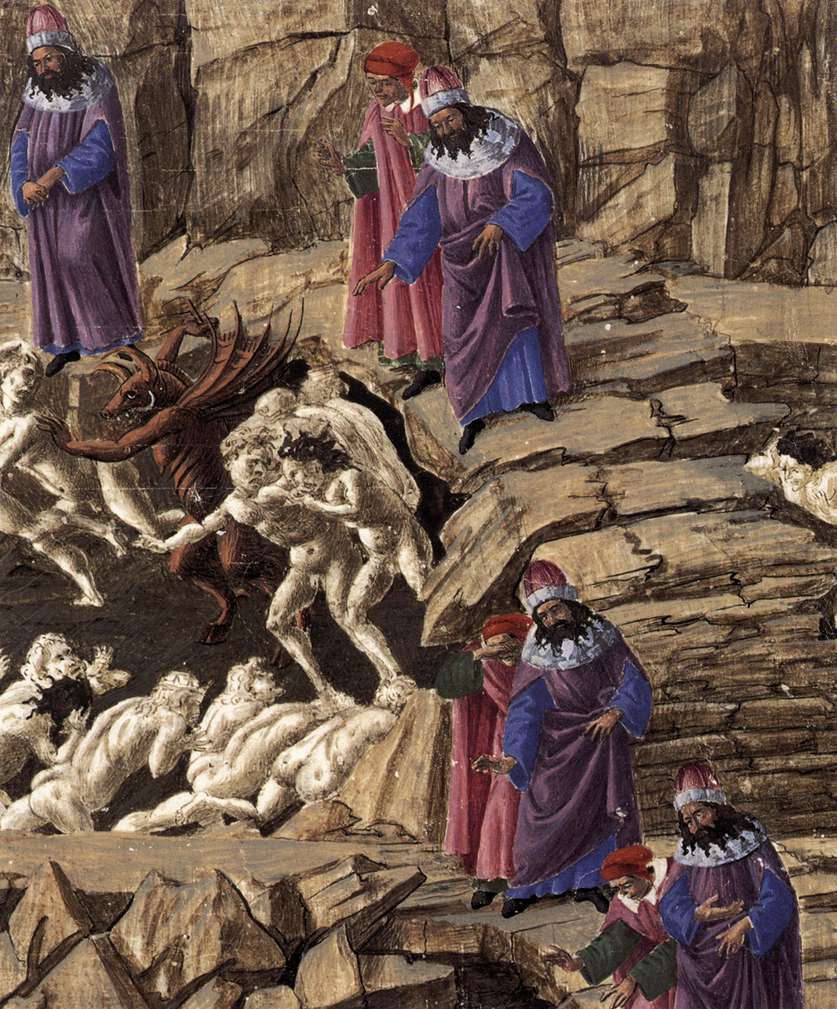

| Sandro Botticelli, La Voragine infernale, from the drawings for the Divina Commedia, detail |

|

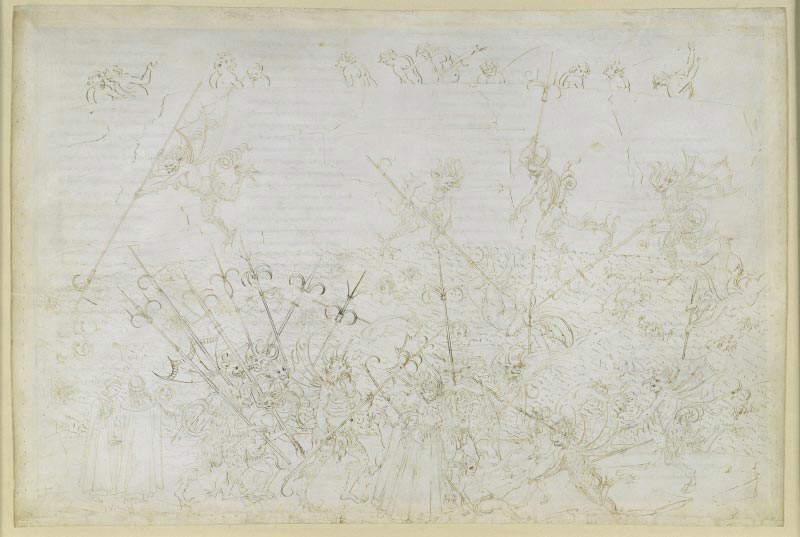

| Sandro Botticelli, Inferno X (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment; Vatican City, Vatican Library) |

The manuscript commissioned by Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici was designed to be consulted from the bottom up. The full text of each canto was contained on a single page, oriented horizontally and divided into four columns, and was written in pen and ink. On each page one can observe the absence of the initial letter of the canto, because it was intended to be illuminated, and of the first verse, because it was written in colored characters. The calligrapher in charge of writing this text was presbyter Nicola Mangona, among the most renowned and capable of the time in Florence. Despite the invention of movable type printing in the West in 1455, it must be considered that many miniaturists and calligraphers were still in business, working for great patron lords such as Mattia Corvino, Federico da Montefeltro, and Lorenzo the Magnificent.

From the beginning, then, these drawings were intended to accompany the poetic text. It can be considered an unfinished series, as the drawings were to be completed by color, and only four of those preserved are. It is not possible to know whether Botticelli was also responsible for the drafting of the color or whether this intervention was entrusted to another executor. The pure drawing, in most cases, is made with a silver point and repainted with pen.

Although, for obvious practical reasons, the drawings are made on separate sheets, they are conceived as a unit, not separated from each other. On the frontispiece of the manuscript is the only finished miniature depicting the infernal chasm created by the fall from Paradise of Lucifer, who can be recognized stuck in the frozen lake Cocito at the end of the infernal realm, in the shape of an inverted funnel. Botticelli offers us a general view of the Inferno that can help the reader orient himself with respect to the geography of this realm of the afterlife.

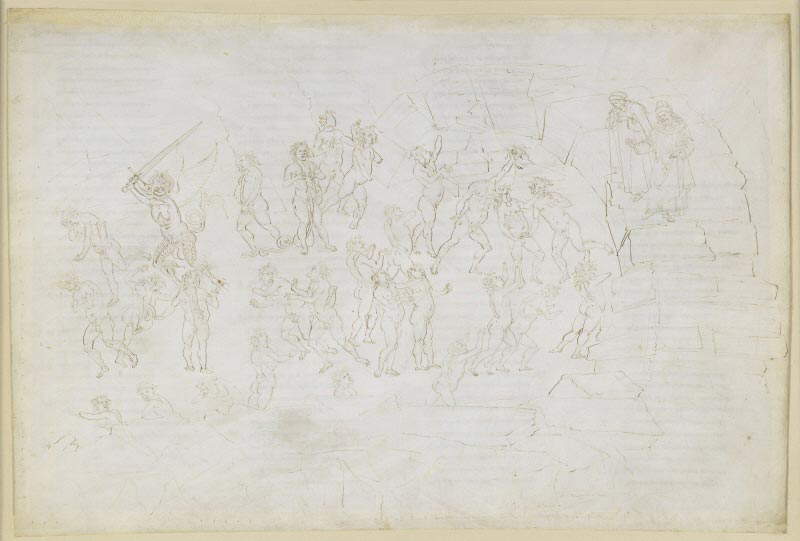

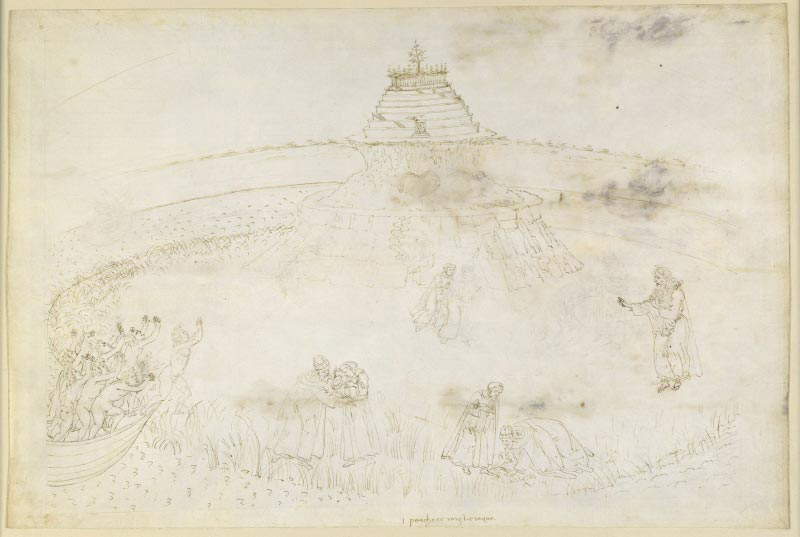

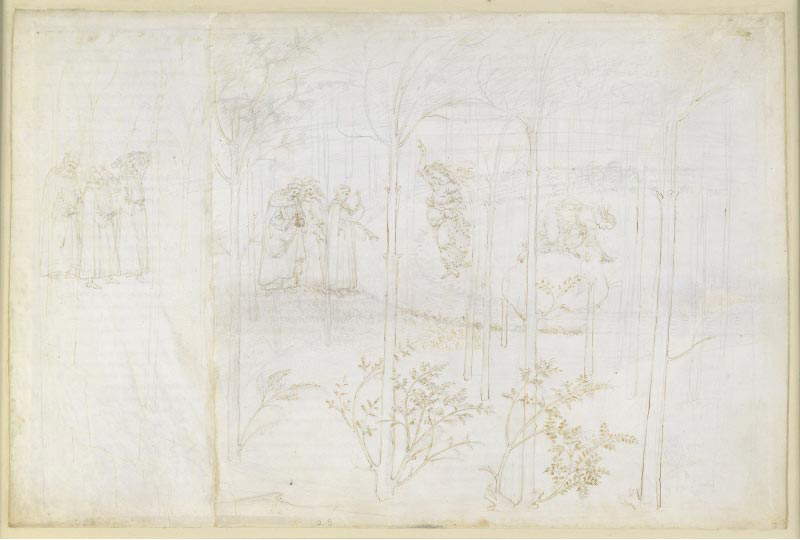

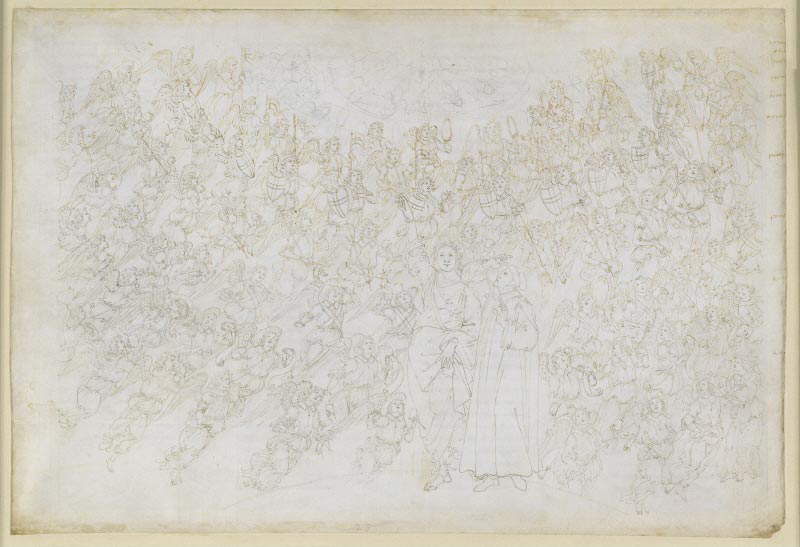

One must agree with the judgment of the Anonimo Magliabechiano and note that this series of drawings is truly wonderful. Dante’s words allow Botticelli to deliver to us through images an incredible visionary world. Especially forInferno and Purgatorio, Botticelli fills the page with figures and details in which to get lost. The painter’s focus is on the journey, not only the physical journey, but especially the journey of inner metamorphosis that Dante makes through the three realms of the afterlife. It is also for this reason that for each canto Botticelli chooses not only to depict a specific episode, such as an encounter with a damned or a penitent, but through the reiteration of the protagonist Dante, wearing the red mantle, and his guide Virgil, wearing the blue mantle, he traverses the entire narrative. Already from the drawing of the first canto of the Inferno, it is possible to grasp this setting: in fact, for each of the three beasts encountered on the way out of the dark forest, there is a ’different’ Dante, in whom it is possible to grasp different reactions and states of mind with respect to the lion, the lion and the she-wolf. Thus, the effect achieved is not only that of spatial subdivision, but also of emotional scanning. Scrolling through the images of the Inferno, one notices how the composition is overloaded with characters, but as mentioned earlier, no specific character or story emerges, as it does in the poetic text. Botticelli does not spare himself in depicting the heartbreak and atrocity of Inferno, features that nevertheless, as in the text, make it terrible and, at the same time, compelling. In some drawings in the first cantica, empty space is almost entirely absent, which will increase instead in the Purgatorio compositions and will be predominant for the Paradiso depictions.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Inferno XIX (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 320 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Inferno XXII (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 322 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Inferno XXVIII (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 320 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Inferno XXXIV (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 322 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Purgatorio I (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 323 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Purgatorio X (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 322 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Purgatorio XV (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 321 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

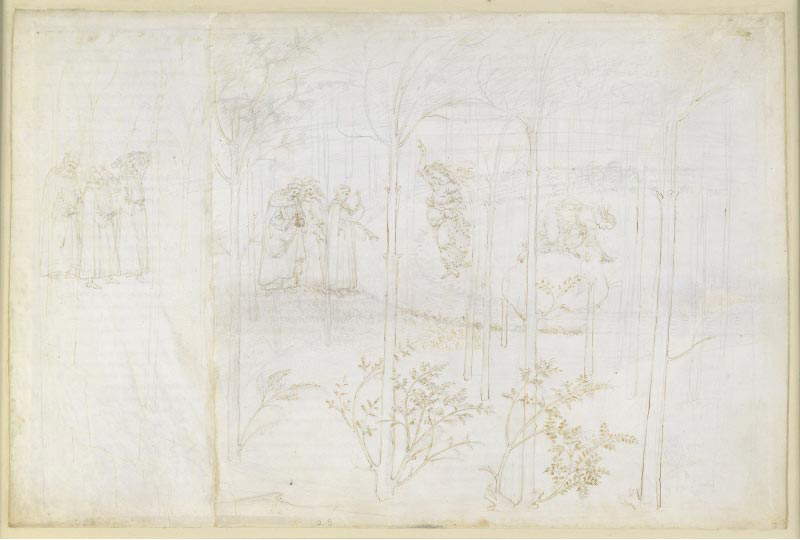

| Sandro Botticelli, Purgatorio XXVIII (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 322 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Purgatorio XXVIII (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 322 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Paradise I (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 321 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Paradiso IX (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 322 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Paradiso XXVIII (1481-1495; silver point, ink and pen on parchment, 321 x 470 mm; Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett) |

Botticelli restores to us through his images the infernal chaos contrasted with divine harmony. The artist does not spare himself in depicting the most gruesome details of Hell: this is the case in canto XXVIII, where the sowers of discord are found, in which Dante himself declares that any language would be insufficient to depict what he has seen. By counterpoise, those damned are either quartered in half deprived of certain parts of their bodies, and in the Botticelli drawing we see precisely these details reproduced. To achieve such a result, in which great fidelity to the text is found, one must assume that Botticelli had read Dante’s Commedia extensively. In Purgatorio the composition is less chaotic, but the reiteration of Dante and Virgil remains. In Paradise, the artist changes his approach markedly: the focus, in fact, is entirely on Dante and his new guide, Beatrice. They are almost always depicted alone, placed within a circle to indicate the heaven in which they are transiting. Compared with the previous canticles, there are no topographical references, a fundamental part of the construction of Inferno and Purgatorio, and the depiction is thus rendered ethereal. The intense and complex dialogues of Dante’s Paradiso are here rendered through a profound interplay of gazes between Dante and Beatrice. Botticelli draws Beatrice with the grace and elegance that distinguish his most famous female figures, whether those belonging to the mythological sphere, such as Venus or Flora, or to the religious sphere, in depictions of the Madonna.

As for chronology, no exact date can be established, but some time references can be taken. The term ante quem is 1503, the year of the death of the commissioner. We must then consider that the first group of drawings with Dante’s theme are for the Commedia commentata da Landino published in 1481; moreover, Botticelli in 1481-82 was in Rome, engaged in the decoration of the Sistine Chapel. It seems reasonable, also on the basis of some considerations about the spelling of the text, to think of a realization during the 1490s for this manuscript, which sees two illustrious Florentines brought together. They lived in a profoundly different Florence: the poet immersed and protagonist in the communal civilization, amidst the struggles of Guelphs and Ghibellines, the painter in the lordly Florence of Lorenzo de’ Medici.

The author of this article: Francesca Interguglielmi

Storica dell'arte, laureata in Arte Medievale presso l'Università degli Studi di Siena. Attualmente si sta formando in didattica museale presso l'Università degli Studi Roma Tre.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.