One could venture a very precise date to establish the “official” beginning of the Veronese Renaissance: July 31, 1459, the day on which the celebrated San Zeno Altarpiece was placed on the high altar of the Basilica of San Zeno in Verona, in the presence of the painting’s author, Andrea Mantegna (1431 - 1506). The work immediately aroused immediate admiration and set an example for all artists, young and old, working in the city: it was a revolutionary painting, bringing to Verona that Renaissance culture that had developed in Padua and was spreading, slowly, throughout the Veneto. A culture made up of interest in the antique, of a precise sense of space, of perspective research, of statuesque monumentality. All these characteristics, already developed by a still young Mantegna (at the time of the creation of the San Zeno Altarpiece, the artist was in fact twenty-eight years old), made their appearance in Verona with the arrival of the altarpiece.

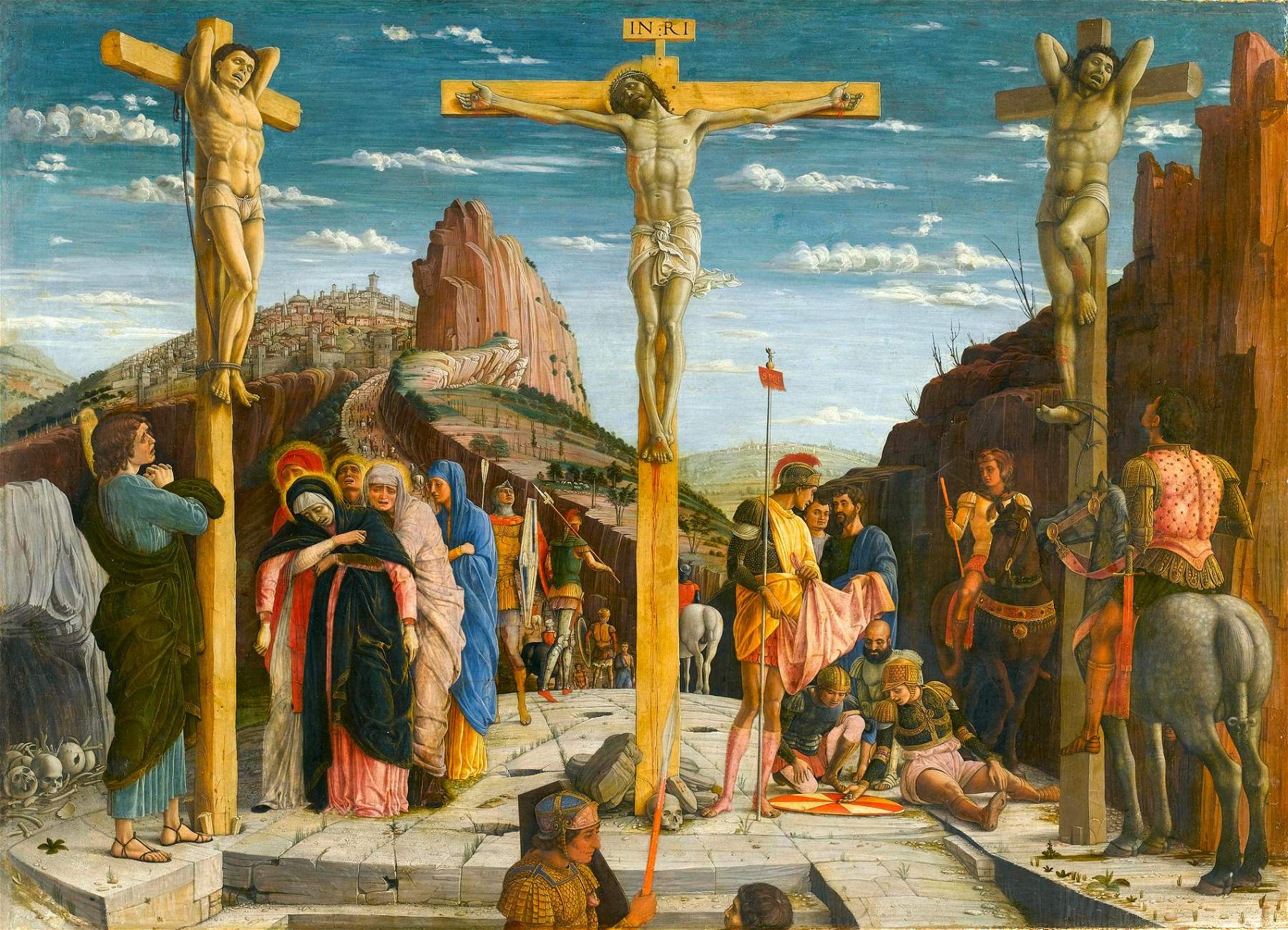

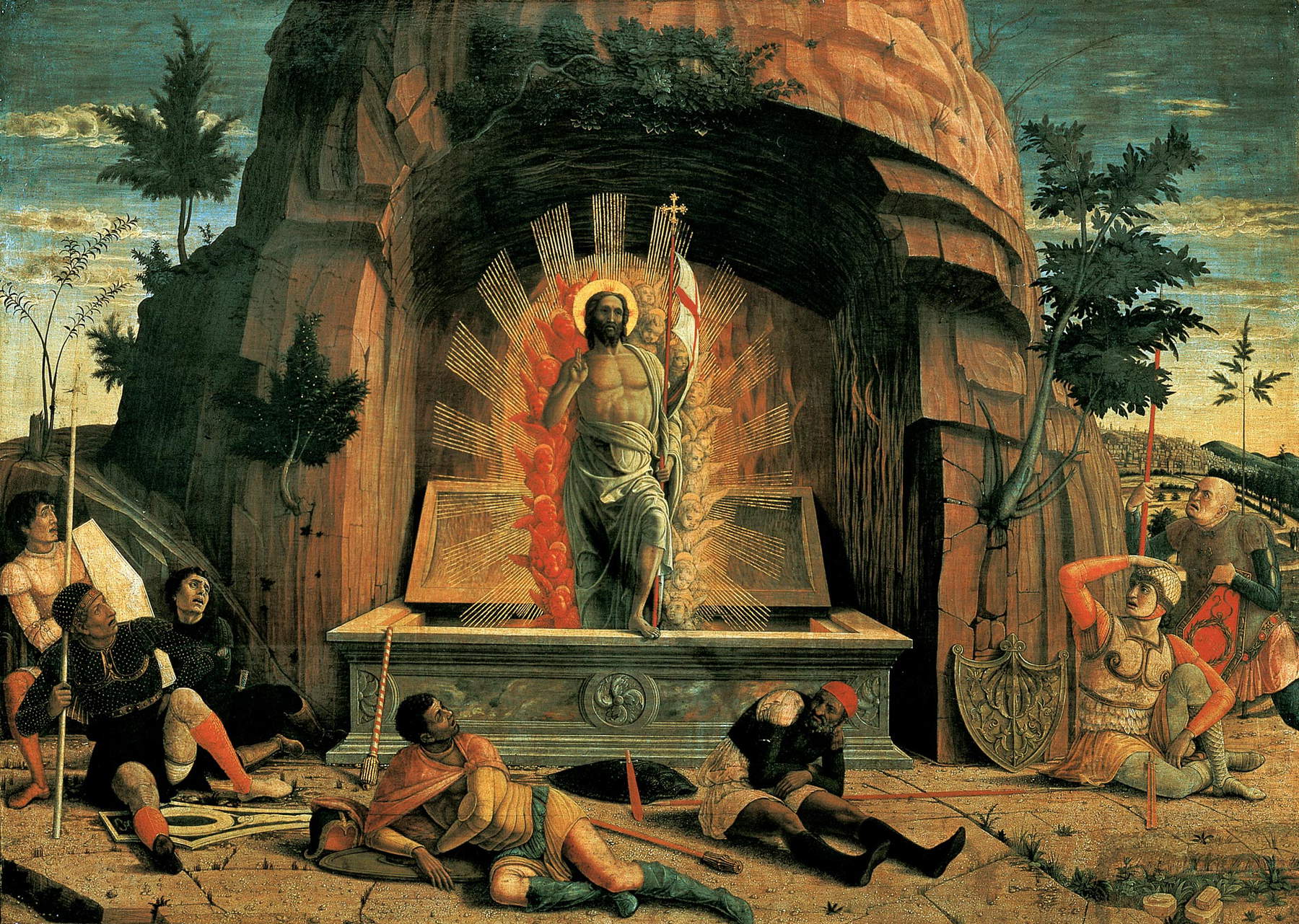

An altarpiece that had, moreover, a very troubled history. Which it is interesting to recall. The commissioner was Gregorio Correr, a member of one of the most illustrious families of the Venetian patriciate. At the time of the commission (we are between 1456 and 1457: unfortunately, the contract has not reached us, but we know that Mantegna began work on January 5, 1457), Gregorio Correr held the position of abbot of San Zeno: steeped in humanistic culture, and probably impressed by what the artist had done in Padua, he noticed that their views were more or less on the same lines, and therefore thought of hiring him. The one with Abbot Correr was a very happy encounter for Mantegna: it was in fact Correr himself who advocated the artist’s name at the Gonzaga court, which would decree the Venetian painter’s fortune. The abbot had been a schoolmate of Marquis Ludovico III Gonzaga during his years of study at Vittorino da Feltre’s Ca’ Zoiosa, and we can think that these relationships facilitated Mantegna’s entry into Mantua. As mentioned earlier, the San Zeno Altarpiece was finished and placed on the Basilica’s high altar in 1459. The altar specially built to house the polyptych would later be removed in 1500, and the work would be displaced as it was moved closer to the apse. Centuries later, the Treaty of Campoformio and Napoleon ’s arrival in Italy subjected the work to the risk of being moved to France. And so indeed it was: the San Zeno Altarpiece was one of countless works requisitioned by the Napoleonic army and sent to Paris. Mantegna’s painting in particular contributed to the first nucleus of what is now the Louvre Museum. However, following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the work returned to Verona, but without the predella, which remained in Paris: what we see today in Verona is a copy (today the individual panels that make it up are divided between two museums: the Crucifixion is in the Louvre, while the Prayer in the Garden and the Resurrection are in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tours). The vicissitudes, however, did not end with Napoleon: during World War I, the altarpiece ran the risk of being taken to Austria. After the battle of Caporetto there was widespread fear of the Austrians entering Veneto: so, for precautionary reasons, the work was disassembled and sent to Florence in order to secure it. Once the war was over, the work returned, still disassembled, to Verona, but it was immediately sent to Milan for restoration: it would return permanently to its city only in 1935. Since then, except for a brief interlude between 2007 and 2009 (again for a new restoration), we see it, in its original frame, inside the Basilica for which it was conceived.

The revolutionary scope of a work arriving in a city still tied to its own late Gothic art, which, later than other places, was beginning to open up to Renaissance novelties, was shocking: because these novelties came all at once. And one only has to take even a cursory glance at the painting to realize the distance it posed from contemporary Veronese artistic production. One of the masterpieces of late Italian Gothic art, Pisanello’s fresco, Saint George and the Princess, in the church of Sant’Anastasia, dated from just twenty years earlier, while a work such as Jacopo Bellini ’s Saint Jerome Penitent (who was, moreover, Mantegna’s father-in-law) preserved in the Museo di Castelvecchio and also still linked to an outmoded imagination was roughly contemporary (it should date from the middle of the century). The art that until then was being produced in Verona was wiped out in one fell swoop. For, with the San Zeno Altarpiece, Mantegna produced what is widely regarded as the first fully Renaissance polyptych in the whole of northern Italy, and consequently, with his work, the artist brought the Renaissance, with all its novelties, to Verona.

The first revolutionary aspect, already conquered in central Italy thanks to artists such as Beato Angelico and Domenico Veneziano, but new for the north, consists in the unified space within which the scene takes place: if until before, in Verona and its surroundings, the polyptychs were rigidly divided and each compartment made history in itself, now the division remains, so as not to create too sharp a break with the past, but what we see beyond the columns dividing the compartments is a whole scene, a single space. This was a conception derived from his study of Donatello’s works for the Basilica of St. Anthony in Padua: in particular, Mantegna took the structure that Donatello had designed for the Altar of the Saint (now lost), and applied it to his San Zeno Altarpiece. And it is also worth noting how Mantegna adopted the expedient of designing a frame with the compartments divided by classical columns, which almost seem to be part of the scene themselves. The impression is that of standing on this side of a loggia, scaled in depth and of which the frame is an integral part, where the figures find their place: in the center, the Madonna and Child together with festive angels, on the left side Saints Peter, Paul, John the Evangelist and Zeno, and on the right side Saints Benedict, Lawrence, Gregory the Great and John the Baptist. Theperspective illusionism with which Andrea Mantegna makes the space described by the painting believable is another of the new aspects of the altarpiece, which would be further explored with the artist’s later research.

The marble loggia is sculpted with medallions within which Mantegna set mythological scenes, while classical putti appear on the frieze. And precisely in the search for links withclassical antiquity lies another reason for the polyptych’s revolutionary scope. It should not be surprising that, in the same scene, motifs taken from pagan repertoires appear together, and elements proper to the Christian religion: for Renaissance men, there was a continuity between Christianity and paganism, and it was thought that the writings of many pagan authors (think of Virgil, to remain in the area in which Mantegna worked) announced in some way the advent of Christianity. And we must then consider that Mantegna nurtured a strong passion for classical art, which he had the opportunity to develop during his apprenticeship in the workshop of Francesco Squarcione, a painter known for his very high antiquarian interests (and, incidentally, typically Squarcionesque are the festoons hanging from the architecture). Thus, many of the motifs that appear in the San Zeno altarpiece are inferred from knowledge of Roman monuments, through casts and reproductions in Francesco Squarcione’s possession: Mantegna would later delve into classical antiquities, later in life, with a direct stay in Rome.

Symbols harking back to classicism as to the era that preceded the advent of Christianity are not the only ones present in the painting, which also has considerable symbolic relevance. Perhaps the most obvious symbol in the entire composition is theostrich egg from which hangs the lantern in the center of the scene, right above the Virgin’s head: it is a reference to theImmaculate Conception, because in ancient times there was a belief that ostrich eggs hatched through the action of the sun’s rays. And the sun has always represented God: God therefore fertilizes the egg through the Holy Spirit and gives birth to Our Lady. The festoons decorating the loggia are laden with grapes, the symbol of the Eucharist, and with apples, the symbol of original sin redeemed by Christ through his sacrifice. The decoration on the top of the Virgin’s throne, in the shape of a wheel, refers instead to the rose window of the Basilica of San Zeno.

As reiterated above, the San Zeno Altarpiece marked the beginning of a new epoch forVeronese art: all the artists of the time began to revise their style to bring it up to date with the innovations introduced by Andrea Mantegna, and in the wake of Mantegna’s lesson a generation of very valid painters originated who kicked off the Veronese Renaissance. Beginning with three young contemporaries of Mantegna: Francesco Benaglio (c. 1432-after 1492), Domenico Morone (c. 1442-1518), and Liberale da Verona (c. 1445-1530), whom we can somewhat consider the leaders of the Renaissance in Verona. The first to take on board the innovations was Francesco Benaglio, who was Mantegna’s contemporary: just three years after the creation of the San Zeno Altarpiece, he produced the Triptych of San Bernardino, a work still preserved in the church of San Bernardino in Verona, a work derived directly from the example of Mantegna’s polyptych, and a work that we can consider the first Renaissance altarpiece made by an artist of the Veronese school. The generation following that of Morone and Benaglio, excellently represented by artists such as Francesco Morone, son of Domenico, Giovan Francesco Caroto, Niccolò Giolfino, Girolamo dai Libri, and others, developed the ideas of their teachers, updating them according to their own training: there were those who, like Caroto, were fascinated by Correggio’s delicacy and sensibility, those who, like Francesco Morone and Girolamo dai Libri, looked to the colorism and naturalness of painters from the Venetian area such as Giovanni Bellini and Antonello da Messina, and there was no shortage of those who, like Niccolò Giolfino, looked to the painting of central Italy, inspired mainly by Raphael. Mantegna, with his altarpiece, had triggered an important process of renewal, which gave rise to one of the most interesting schools in our art history.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.