Standingon the balcony to overlook the world or to talk with people with whom we wish to interject to exchange ideas and pass the time: whether we scan the horizon alone in silence or gather in the company of our loved ones, the balcony is a place of escape, between the home environment and the outdoors. A place where we feel protected because it is part of our home, but at the same time sharing with our surroundings. Today, as in the past, we look out onto the balcony, especially on beautiful sunny days, and often, throughout the history of art, the balcony has been the setting for paintings: lonely women or lonely men, wives and husbands together, mothers with their children have populated through the centuries the balconies of every city in the world. We try, here, to propose some of them, from the early 19th century to the first decades of the 20th century.

Preserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York is a painting attributed to Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Fuendetodos, 1746 - Bordeaux, 1828) that depicts the theme of women on the balcony: it is, however, a work that is rather disturbing, since behind the two maidens in the foreground are two male figures, one standing and the other seated, all covered in their dark garments with a rather menacing appearance. The girls are two majas, a Spanish term for a commoner who likes to dress elegantly, a beautiful and provocative young woman who is often juxtaposed with the figure of a prostitute: they are in fact wearing long white dresses with gold decorations, with light veils on their heads. They are both leaning against the railing, one with her elbow and the other with her hand, and seem to be smiling. The stark contrast the female and male figures is thus very evident: smiling and characterized by light colors the one, somber and dark colors the other.

Majas on the Balcony, this is the title of Goya’s work, also presents a particular geometric structure: the two majas are inserted in a rhombus, cut in half by the balcony railing; the latter results in the side of a rectangle constructed by drawing a parallel line above the hat of the man on the left of the painting; furthermore, this rectangle can be divided into two squares, inside which are respectively the man and the woman on the left and the man and the woman on the right, respecting the diagonals of the rhombus. This Metropolitan painting, made between 1800 and 1810, would be a variant of another painting of the same subject, now in a private collection in Switzerland, and refers to another work by Goya of similar subject, which belongs to the Fundación Juan March, depicting Maja and Celestina at the balcony. Again, the maja, beautiful, young, and brightly dressed, is contrasted with the old woman behind her who watches over her in the shadows. In fact, La Celestina is another typical character in Spanish literature that indicates an old maid.

|

| Francisco Goya, Majas on the Balcony (1800-1810; oil on canvas, 195 x 125.5 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

| Francisco Goya, Maja and Celestina on the Balcony (1808 1812; oil on canvas, 166 x 108 cm; Palma de Mallorca, Fundación Juan March) |

Despite the decidedly different social context, Majas on the Balcony was a source of inspiration, composition-wise, for the French artist ÉdouardManet (Paris, 1832 - 1883), who between 1868 and 1869 created The Balcony, a work preserved at the Musée d’Orsay. As in Goya’s painting, the characters are depicted behind the railing that reaches about halfway through the entire painting, and here, too, the young women appear in the foreground and in full light compared to the two men who remain in the back. Two female and two male figures, like the protagonists in the previous work, but in this case one is standing between the two maidens, while the other remains blurred in the half-light. This is a scene of bourgeois life: the balcony thus becomes a symbol of affluence from which to watch what was happening on the Parisian boulevard , probably in one of the most affluent neighborhoods of the French capital. The protagonists of this work are all friends of the artist herself: the most recognizable is the painter Berthe Morisot (Bourges, 1841 - Paris, 1895), the young woman seated in the foreground; it is also the first painting in which Morisot modeled for Manet, since several were added to this one, including the famous portrait of the painter with a bouquet of violets also housed in the Musée d’Orsay. The other figures depicted would be the painter Jean Baptiste Antoine Guillemet, the violinist Fanny Claus, and Leon Leenhoff, considered by many to be Manet’s son. In addition to the four mentioned above, a small black and white dog is depicted next to Berthe Morisot’s white dress. Manet’s Balcony was seen as a provocation because of the vibrancy of the colors and the strong contrast between the women’s white dresses and the background in the shadows, so much so that at the 1869 Salon the painting received a particular criticism, namely that its author was competing with the painters. The work was purchased in February 1884 by Gustave Caillebotte (Paris, 1848 - Gennevilliers, 1894) and remained in his collection for a good ten years, until 1894, when it became the property of the state and was exhibited since 1896 at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. Only since 1986 has it been kept at the Musée d’Orsay.

|

| �?douard Manet, The Balcony (1868-1869; oil on canvas, 170 x 124 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Bethe Morisot, Woman and Child on the Balcony (1872, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm; private collection) |

And continuing this sort of chain between artists in the depiction of the balcony, both Berthe Morisot and Gustave Caillebotte, both exponents of ParisianImpressionism, dedicated their works to this place in the home. In a private collection is Woman and Child on the Balcony, which the painter executed in 1872. This time the point of view is different from the previous paintings mentioned, for while both Goya’s and Manet’s paintings depict balconies and human figures frontally from the outside, here they are portrayed from the inside, that is, on the same plane as the characters. The woman is dressed in an elegant black dress, wearing a bonnet of the same color according to the fashion of the time and holding a rosy-colored parasol, while the little girl is wearing a pretty white and blue dress with a bow in her hair. Both are looking at the Parisian landscape below. In the distance, a large building surmounted by the golden dome can be glimpsed; it is probably the Hôtel National des Invalides.

Gustave Caillebotte instead made Un balcon. Boulevard Haussmann and The Man on the Balcony. Boulevard Haussmann, both in the 1880s, now in a private collection. The boulevard reflects the renewal of the city, with elegant buildings, wide, straight streets, and trees. In the first painting, two men stand on an elegant balcony, one of whom, the one leaning out from the balcony to look at the boulevard below filled with green trees, is dressed in full regalia with a top hat on his head; the other man has one hand in his trouser pocket and is leaning against the wall of the house, but his gaze is also facing the same direction. In the second painting, a smartly dressed man leans his right hand against the balcony railing, leaning forward slightly, and rests his left hand on his hip. Again, the protagonist is observing the boulevard, but here the point of view is of someone inside the house, as we can see the window sash on the right, with the glass reflecting the man’s image, and the red-and-white-striped ruffled sunshade curtain.

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, A Balcony. Boulevard Haussmann (ca. 1880; oil on canvas, 69 x 62 cm; private collection) |

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Man on a Balcony. Boulevard Haussmann (c. 1880; oil on canvas, 116.5 x 89.5 cm; private collection) |

The Italian Federico Zandomeneghi (Venice, 1841 - Paris, 1917), who adhered to Impressionism and shared its colors and themes, also depicted a Woman on the Balcony, an oil on canvas signed but undated, owned by the Viareggio Society of Fine Arts. As in the Caillebotte painting mentioned above, the point of view is again from inside the dwelling, and the reflection of the woman in the window pane on the right is also noticeable here. The young woman is leaning with both elbows on the railing and is looking at something to her right in the rich, lush vegetation in front of her. Her delicate face is slightly in profile, her hair is gathered in a soft bun, and she is wearing a pink blouse with a white collar and a blue skirt. It is a very refined painting characterized by pastel tones.

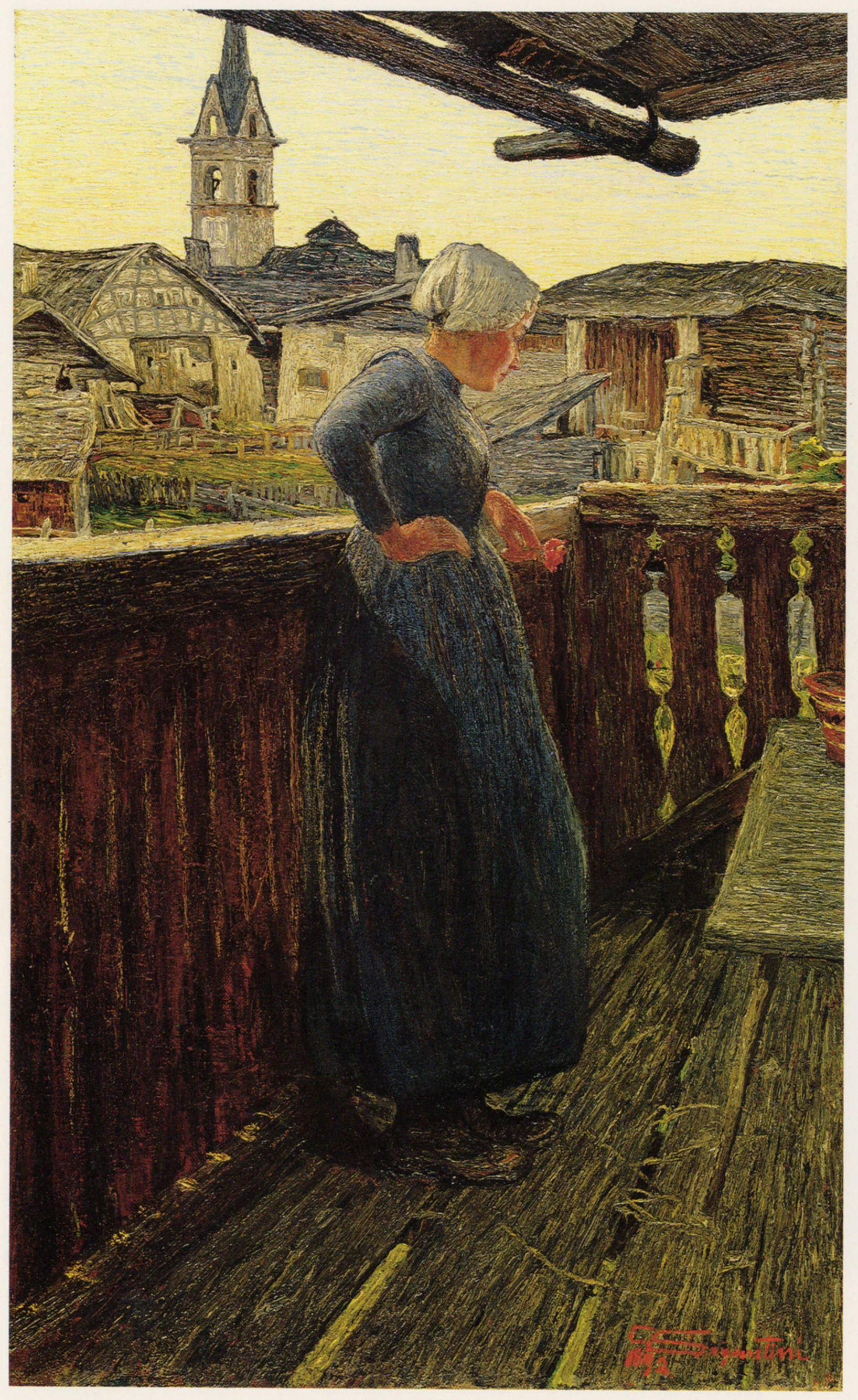

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, precisely in 1893, Giovanni Segantini (Arco, 1858 - Pontresina, 1899) also made his own contribution in depicting a woman on a balcony. From Spain to France to Italy, we come to Switzerland with this painting. The painter was in Savognin, a farming village in the canton of Graubünden, and indeed a young peasant woman is portrayed in the work in typical clothing: a dark dress and a white bonnet that completely hides her hair inside. She appears pensive, resting, her back turned to the landscape, with one arm resting on the balcony railing and her other hand on her hip. Wood becomes the main element in this work. The woman is immersed in the surrounding landscape, with the characteristic houses of the Swiss canton and a tall bell tower towering in the distance. Noteworthy is the brightness of the painting, which refers to his “pure search for light,” as the artist himself stated, typical of the Divisionism he was inspired by. A light that spreads evenly from the sky and is reflected on the houses, courtyards and the woman’s face. The signed and dated work is in the Kunsthaus in Chur, a depository of the Gottfried Keller-Stiftung Gallery in Bern.

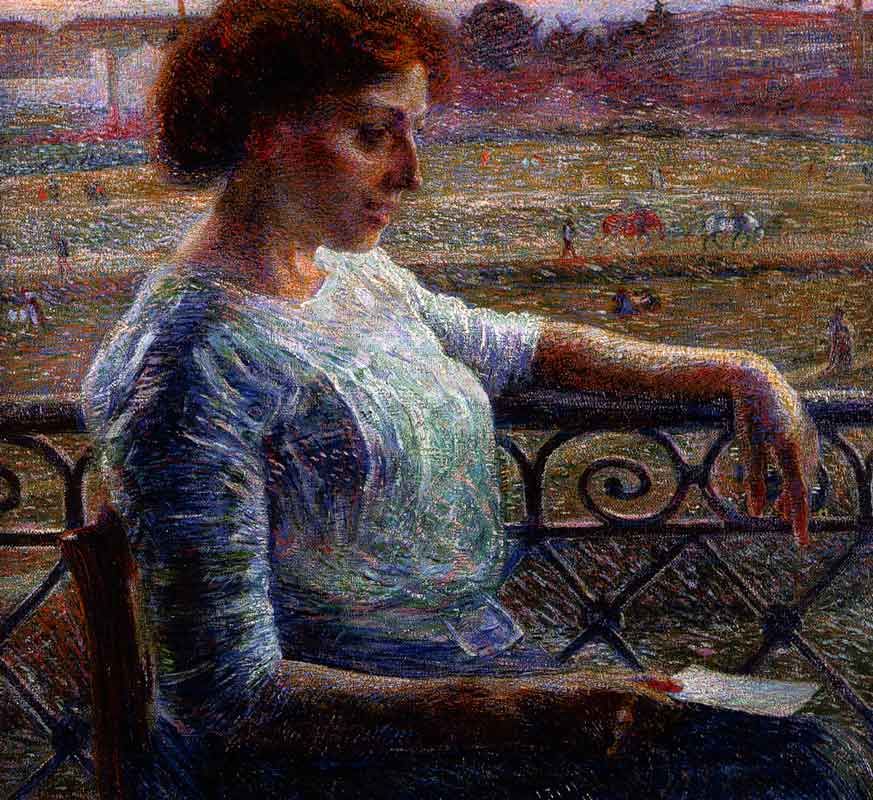

Immersed in the surrounding landscape also appears Umberto Boccioni ’s (Reggio Calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916) sister Amelia in the painting in which the artist depicted her in 1909. The foreground is entirely occupied by the woman sitting in profile next to the balcony railing, and all around can be recognized meadows, people walking with animals, and buildings can be glimpsed in the distance. The young woman is sitting on a chair and rests her arm along the railing, which becomes a unifying element between inside and outside as the railing divides the composition into two parts. She holds a sheet of paper in her right hand, which she has probably just finished reading, and perhaps what was written caused her to look dreamy, with a barely sketched smile, which is evident in her facial expression. The dress she is wearing is a union of light and color, including reflections ranging from the deepest blue to purple, green, and white: it is in fact a work of the painter’s Divisionist phase, as can be perceived from the attention to brightness and separate strokes of color.

Finally, the painting by Piero Marussig (Trieste, 1879 - Pavia, 1937) depicting Figures on the Balcony dates from 1920: it seems to be a recent scene, where the protagonists are a man and a woman; the former is sitting on a small wooden deckchair and observes the view while holding his left arm slightly raised, on the balcony railing; the latter is standing and leaning on her elbows, while she too is looking at the landscape. All around one can see neither lawns nor trees, but tall buildings: one is thus in the middle of an undefined residential neighborhood , that is, one could represent any balcony in any city. A moment of everyday life that could unite, even today, everyone who has a balcony on which to stand in the open air, reflect or exchange a few words.

|

| Federico Zandomeneghi, Woman on the Balcony (oil on canvas, 46 x 38.5 cm; Viareggio, Society of Fine Arts) |

|

| Giovanni Segantini, On the Balcony (1893; oil on canvas, 66 x 41.5 cm; Chur, Kunsthaus) |

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Sister Amelia on the Balcony (1909; oil on canvas, private collection) |

|

| Piero Marussig, Figures on the Bal cony (1920; oil on canvas, 90 x 75 cm; private collection) |

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.