On February 5, 1629, with the reigning pope of the House of Barberini, Urban VIII, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) was appointed as the new architect of the Fabbrica di San Pietro, just days after the death of his predecessor Carlo Maderno (Capolago, 1556 - Rome, 1629). The latter had already been entrusted by Pope Paul V at the beginning of the century with the task of erecting the two bell towers of the Petrine basilica. However, the operation had turned out to be more problematic than planned, mainly because of the presence of underground streams that made the ground unstable and thus complicated the construction of the foundations. Thus neither the commissioner, who died in 1621, nor the architect, who died eight years later, had been able to see the completion of the undertaking, which passed into Bernini’s hands with his appointment to the Fabbrica’s top management. In January 1638 the task was officially assigned to him.

Maderno had come to build the two structures up to the height of the façade’s attic, and from here he had to take over from the new architect, who, however, did not merely supervise the continuation of the work according to his predecessor’s program, but, at Pope Urban’s request, rethought the bell towers and presented a plan that called for them to be more elaborate and, above all, taller (they were to rise another 65 meters above Maderno’s attic).

For the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, in 1641, the first bell tower, the southern one, was finally completed, except for the still temporary wooden roof. Immediately after the festivities, however, Urban VIII, dissatisfied with what had been accomplished, unexpectedly commanded that the wooden pyramid as well as the third order of the bell tower be dismantled.

This was a very hard blow for Bernini and, as if this were not enough, some worrying cracks made their appearance on the facade of the Basilica shortly thereafter. At this point many rumors began to circulate about the excessive weight of Bernini’s bell tower and about the alleged structural damage it caused to the entire building. The following year the work was officially halted. But, as Sarah McPhee suggests in her Bernini and the bell towers: Architecture and Politics at the Vatican, it can be assumed that the financial difficulties of the papal state, largely attributable to the costs of the Castro War undertaken by Urban VIII, had influenced the pope’s decision not to reopen the site, far more than doubts about Bernini’s abilities as an architect.

In any case, to worsen Gian Lorenzo’s already rather difficult situation was added, in July 1644, the death of Pope Barberini, who, although he had criticized the artist on this occasion (and not only) had been his most indefatigable patron, to the point of making him the principal interpreter of his own pontificate. Urban’s demise was followed by the election of Giovan Battista Pamphilj, who reigned under the name Innocent X. The new ruler immediately manifested a decisive disapproval of his predecessor’s actions, particularly with regard to his uninhibited handling of money, and an equally obvious aversion to the entire Barberini household.

As it is easy to imagine, therefore, in such a changed scenario, the privileged professional relationship that had linked Bernini to Urban VIII for twenty years proved to be a significant obstacle for the artist in his relations with the newly elected pontiff, at least in the early years. And it was precisely at the behest of Innocent X that, in 1646, the affair came to a conclusion perhaps even more unfavorable to Gian Lorenzo than he had feared: his bell tower was torn down, the works were abandoned and the artist’s property seized as a guarantee against any further damage that might have manifested itself in the structure of the Basilica.

|

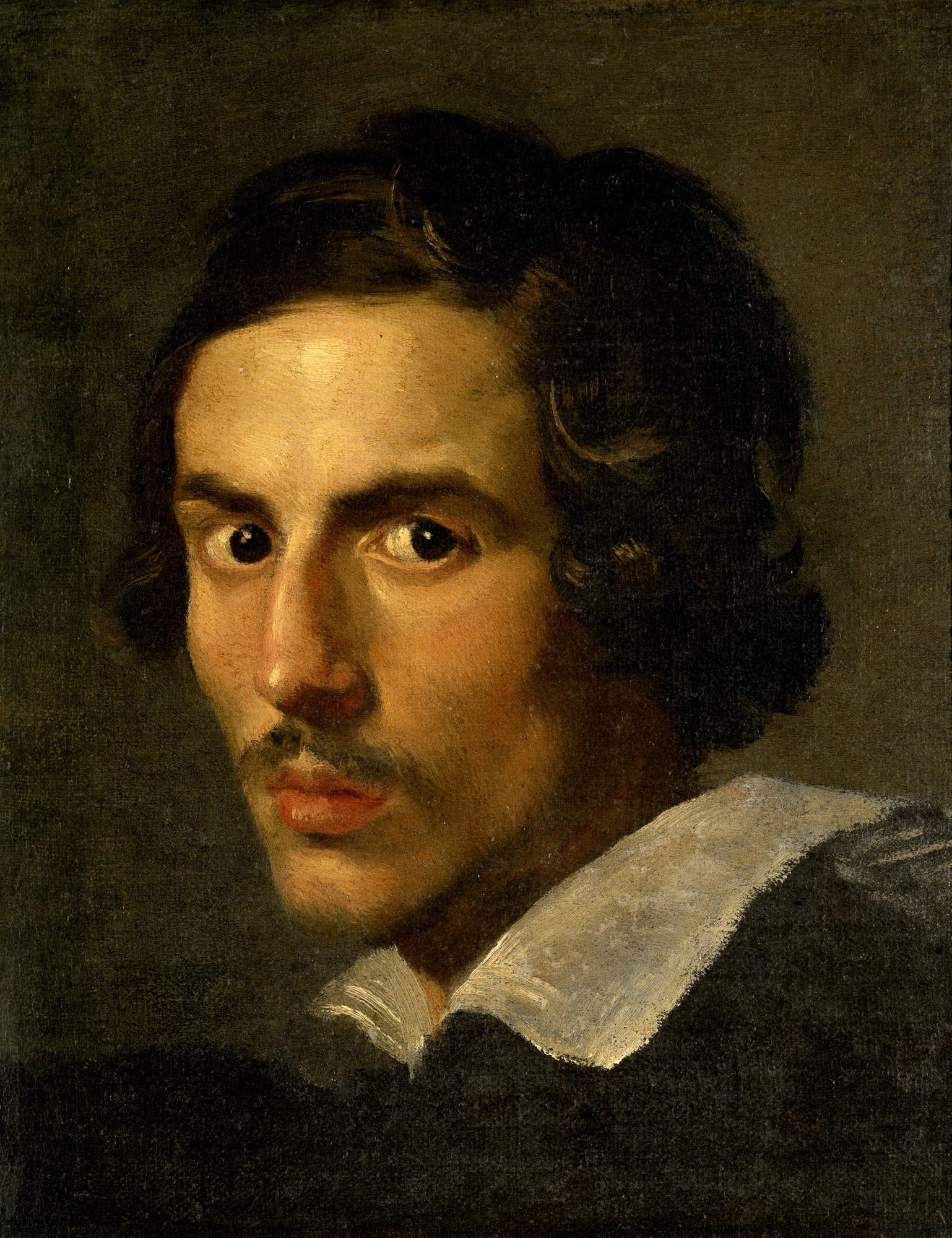

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Self-Portrait (c. 1623; oil on canvas, 38 x 30 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650; oil on canvas, 140 x 120 cm; Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj) |

|

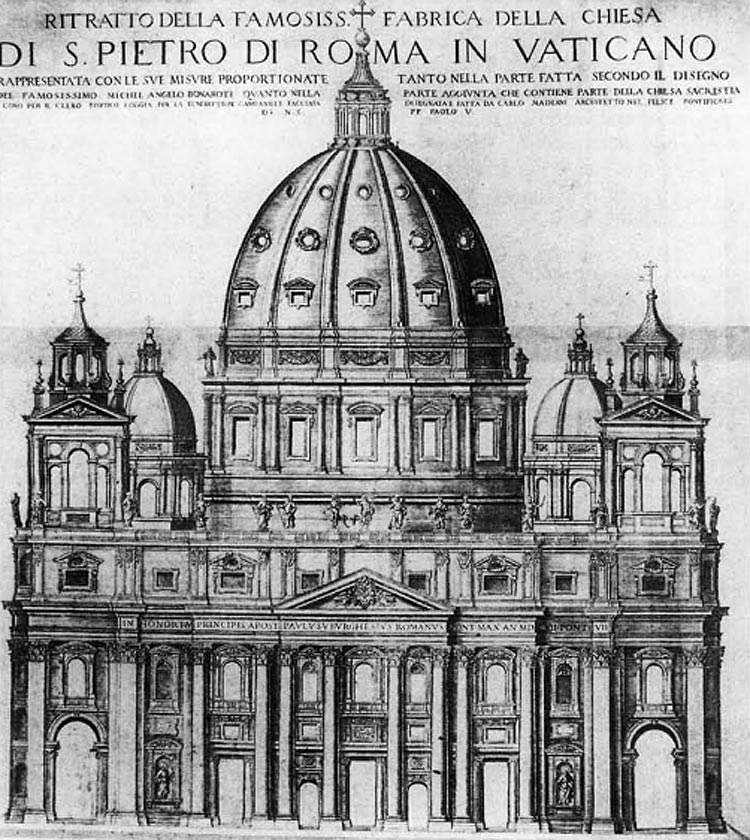

| Matthaeus Greuter, The facade with bell towers of Maderno’s final design for the extension of St. Peter’s (1613; engraving) |

|

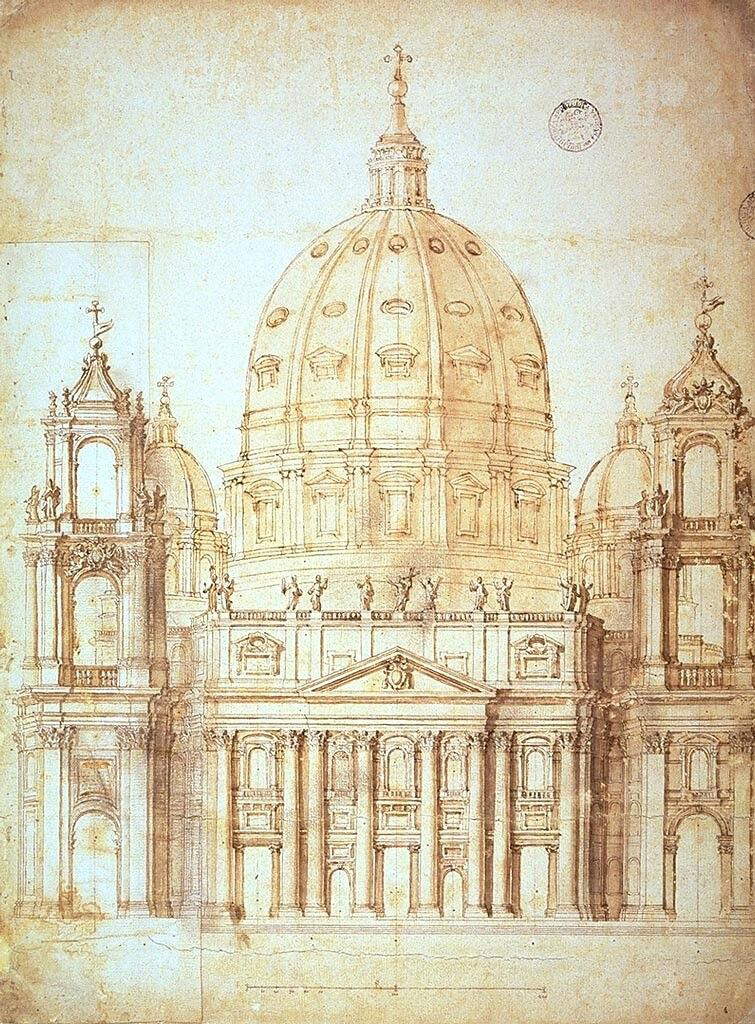

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Proposal for the facade of St. Peter ’s (1645; black pencil, brown ink and gray and brown watercolor on paper; Vatican City, Vatican Library) |

Understandably, Pope Pamphilj, before deciding what to do with what was left of the bell tower, had ordered a series of meetings of the Congregation of the Fabbrica in order to shed light on the static condition of St. Peter’s, yet, according to the testimonies that have come down to us, even today it is difficult to identify a connection between what was ascertained during these meetings and the pontiff’s final resolution.

Filippo Baldinucci, in his Vita del Cav. G. L. Bernino , wrote that Innocent first wanted to listen to Bernini, questioning him about what he had done, and that the artist had defended himself without hesitation, giving his own reasonable explanation of what had happened: "He then added that he was of the opinion that the cause of the movement of the facade was the settling that the construction of the bell tower had done, which is usual in any building of extraordinary grandeur.

Obviously, the Congregation had also sought the opinions of other architects, including that of Bernini’s most valid rival, Francesco Borromini (Bissone, 1599 - Rome, 1667), who, Baldinucci recounts, “where the other opponents of Bernino in bringing their contradictions did not know how to speak of it except with istima and respect, [...] in the presence of the Pope inveighed against him, whole-heartedly and with all zeal.” The Ticino artist’s doggedness had certainly succeeded in fueling Innocent’s doubts, but within limits, considering that, even on the strength of an evidently positive outcome of the examination of the foundations, the pope had initially limited himself to ordering the southern bell tower to be lightened. Moreover, until October 1645 the congregation had asked the architects to submit new plans for the continuation of work on the towers, a sign that they intended to move forward. Instead, as mentioned above, in February 1646, Innocent decided to abruptly close the entire chapter with the order to demolish everything up to the height of the facade that had been built by Gian Lorenzo.

In 1713, when Bernini had been gone for over thirty years, his son Domenico published a biography of him (on which he had been working for years and which he had begun precisely at his father’s request) in which he obviously gave much space to the painful history of the campaniles and its consequences. In the text, after an account of the affair, the author recounts that his father “at that same time, when he seemed abandoned by fortune, made Rome see the most beautiful Works, that he had ever done, authenticating with deeds his valor, which by his Adversaries was discredited with words, persuaded eziamdio, that just as the false one can take vigor from the prestezza, so the truth of his good faith would rise again more beautiful with dwelling, and with time. And this same sentiment, which was a consolation to him, he exhibited to us with a marvelous group, in which Time uncovering Truth is represented.” The sculpture to which Domenico refers is Truth Unveiled by Time, to whose workmanship Gian Lorenzo devoted himself on his own initiative between 1646 and 1652, moved by a desire to make marble speak for itself.

So Bernini began meditating on this work in the very year of its resounding débâcle, a period to which the first of the drawings relating to the sculpture, now preserved in Leipzig at the Museum der Bildenden Künste. But, significantly, he devoted himself more intensively to the work after 1651, that is, after the Fountain of the Four Rivers had publicly (and especially in the eyes of Innocent X) reaffirmed the truth of his greatness as an artist and , in particular, after his daring choice to have the fountain obelisk rest in false, on a marble rock empty in the interior, had definitively proven his ability to handle large structures and their relative weights.

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, La Verità svelata dal Tempo (1646; chalk on paper, 252 x 369 mm; Leipzig, Museum der Bildenden Künste) |

|

| The agonal obelisk placed on the Fountain of Rivers. |

And it is enough to read the passage that Gian Lorenzo dedicated to Truth in his own will to understand how much the story of that sculpture was indeed linked to his own experience: “And because of my works, not without reason, I have retained near me the statue of Truth discovered by Time, therefore falling this statue under the present testamentary disposition, I want it to be in the house where the the first-born, in order to have always and in perpetuity a memory, in my descendants, of my person, as also because looking at that, all my descendants will be able to remember that the most beautiful virtue in the world consists in truth: For, in the end, this is discerned by time.” Nevertheless, in 1924 his heirs placed the statue on deposit at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, where it is still kept. Three decades later the Italian state purchased it.

Bernini sculpted a nude woman with her head reclined in an attitude of dreamy abandon, portrayed her seated on a boulder, and, in adherence to the iconography canonized by Cesare Ripa, placed a small sun in one hand and the globe under one foot, signifying that she, the Truth, is illuminated by divine light and is greater than anything earthly. Behind the figure is a voluminous raised cloth, which evidently covered her at an earlier time.

The statue expresses a vibrant sensuality in the softness of the unveiled body, aided also by the more than casual position in which it has been rendered, with its legs spread apart. As Matthias Winner notes in his essay Veritas, published in 1998, although such a posture does not show “sufficient decorum as should be the case in a female nude,” the figure communicates “a quiet abandonment in its nudity, which has nothing impudent about it. It is part of the intimate essence of truth to offer itself without veils to the true light”: nuda veritas."

The artist used only one block of marble. Moreover, the sculpture still clearly shows the various stages of workmanship: next to the surfaces perfectly finished with polishing, one can see parts that have just been rough-hewn. The back has only been rough-hewn, and even on the sides the marble shows unfinished areas; indeed, it is well known that Bernini often carefully perfected only the parts that were to be visible. Regarding the nude body of the Truth, on the contrary, Tomaso Montanari, in his 2004 monograph dedicated to the sculptor, notes that “The metaphorical luminous splendor that is associated with the revelation of truth finds its equivalent not only in the attribute of the sun supported by the statue, but visually emanates from the entire female body, polished enough to reflect the light, and in calculated contrast to the shadow that inhabits the large drape, dense with folds.”

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, La Verità svelata dal Tempo (1646-1652; Carrara marble, height 277 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese, inv. CCLXXVIII) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Truth Revealed by Time, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Truth Revealed by Time, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Truth Revealed by Time, detail. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Truth Revealed by Time, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Truth Revealed by Time, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Truth Revealed by Time, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre sull’Arte |

In any case, the work was not finished; according to the project of its author as witnessed to us by some drawings, in fact, the Truth was to be surmounted by its elderly father, Time, endowed with sickle and wings and caught in the act of unraveling the cloth from above, thus revealing it to observers. Such drawings include the Leipzig pencil study already alluded to. It is important to point out that, as Rudolf Wittkower first observed in 1966, this sketch was in good likelihood aimed at the realization of a painting or an engraving, in light of the general graphic and perspective layout, but especially because it would be difficult to understand what the meaning of the horizontal line drawn in the background would be, if it were considered, instead, a design for a sculpture; unless one assumes a relief. Thus, there is a real (and fascinating) possibility that Bernini initially thought of expressing in a painting what he later sculpted in marble.

Let us return, however, to the figure of Time. Testifying to the artist’s desire to include this second character are not only the aforementioned drawings, but also a number of sources of the time. The first to mention a model of the sculptural group that included Time was the Duke of Bracciano Paolo Giordano II Orsini, who had the opportunity to see it in 1647 in Bernini’s studio, and informed Cardinal Mazzarino about it in a letter. From the text we learn that parts of the sculpture would be made larger than life-size (the Truth actually measures almost three meters) and that they could be transported separately. The duke, in particular, considered it important to get this last piece of information to Mazarin because at that time there was a real possibility that the cardinal would purchase the work; it being understood that it was not with this intention that Bernini had begun sculpting it. And in any case the thing did not go through, because the cardinal, in essence, made Bernini’s departure for Paris a condition for the purchase, but the latter declined. Instead, he went to France in 1665 at the request of King Louis XIV.

In his Journal du voyage du cavalier Bernini en France, the courtier Paul Fréart de Chantelou recounts this sojourn, and in one passage reports an exchange between Bernini, the sovereign and various court figures on the Truth revealed by Time. “The lord of Créqui then spoke of the statue of Truth, which is with Bernini himself in Rome, as a perfectly accomplished work. Bernini said that he made it to leave it to his family and that the figure of Time, which unveils Truth, is not yet finished [...]. He said that in the model he included columns, obelisks, and mausoleums, and that these things, which appear to have been torn and ruined by time, are the ones that support the figure of Time: without them the statue could not support itself. ’Although it has wings,’ he added with a laugh.” So, although by that time the Truth had already been made as we see it today, Bernini had not yet abandoned the idea of completing the original project, and indeed the block of marble in which the figure of Time was to be carved remained in front of the sculptor’s house until his death, and only then was it sold by the family. Moreover, Chantelou’s piece clearly reveals that, in Bernini’s intention, Time would have been represented in the dual role of revealer of Truth and destroyer, thus allowing the contextual development of the theme of Vanitas. Today we know that none of this was ever realized; moreover, no one protested that the work was not completed because, as we have seen, it was executed by the artist completely autonomously, without the intervention of any patron.

In the course of his career Gian Lorenzo returned to the theme of Truth Revealed several times. In one instance he had the opportunity to depict Time in the act of revealing his daughter, Truth, to the viewer, although he did not execute the female figure at all. This is an unfortunately lost work, a mirror commissioned by Queen Christina of Sweden, who came to Rome in 1655.

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Drawing for the Mirror of Christina of Sweden (ca. 1656; pen, watercolor and chalk on paper, 230 x 188 mm; Windsor, Royal Collection) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Tomb of Alexander VII (1672-1678; marble; Vatican City, St. Peter’s) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Study for the Tomb of Alexander VII (c. 1662-1666; pen, watercolor and chalk on paper, 440 x 307 mm; Windsor, Royal Collection) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Tomb of Alexander VII. Ph. Credit Karel Jakubec |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Tomb of Alexander VII, detail of the skeleton. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Tomb of Alexander VII, detail of the Truth. Ph. Credit Javier Carro |

Of the artifact we possess some drawings, including a preparatory study from around 1670, made by Bernini and now preserved at Windsor Castle in London. Thanks to these testimonies, we know that the precious piece of furniture was decorated in a very special way: one could admire, in the upper part, a gilded sculpture of the old winged Time, intent on removing a curtain, thus uncovering the image of the person who was using the mirror, hence the queen. In this way, the woman’s image would have appeared as the fruit of Time’s revelation, replacing the depiction of Truth. But the intent was anything but flattering: the truth told by the mirror was, in fact, that of the slow fading of beauty and youth. So, again, a Vanitas.

In the tomb of Pope Alexander VII in St. Peter’s, made between 1672 and 1678, Bernini (who designed it and then entrusted most of the execution to other sculptors) wanted to insert a Truth among the allegories placed in the lower part of the monument. The marble figure clutches a golden sun to her chest and rests her left foot on a globe, but unlike the statue in the Galleria Borghese, she is not nude. In fact, she was originally, to a large extent. In fact, from beneath the base on which the portrait of the kneeling pope is placed, emerges a bronze winged skeleton who, shaking an empty hourglass to remind us that Alexander’s earthly time is over, shakes off a splendid Sicilian jasper blanket, pulling it away from the body of Truth.

The fact that it was a papal tomb and its location in the Petrine cathedral ended up exerting a significant constraint on the artist’s freedom, prompting the already rigid pontiff Innocent XI (born Benedetto Odescalchi, who ascended to the papal throne in 1676) to order Bernini, in 1679, to cover that nudity. The artist then was forced to intervene by making the bronze robe then painted white that we still see today. However, the original idea was powerful and can still be intuited; as Erwin Panofsky effectively writes in his 1964 Tomb Sculpture, “By proclaiming the triumph of Time over Life, Death achieves, albeit unintentionally, the triumph of Truth over Time.”

Innocent XI’s order was as inescapable as it was inevitably laden with symbolic meaning, since the statue he wanted covered depicted nothing but Truth, and it was certainly an extremely unpleasant task for Bernini: both the biography written by his son Domenico and that of Filippo Baldinucci tell us this. Domenico states that in carrying out the work his father “felt a very great difficulty,” and in both texts (which in many passages are almost identical) we read that the cause of the sculptor’s discomfort stemmed from having to “accommodate one thing above another made with a different intention.” Moreover, according to Chantelou’s Journal, in 1665, Gian Lorenzo had told Louis XIV that in Rome there was a saying, “Truth is found only in the house of Cavalier Bernini.” And the reference was obviously to the naked, sensual marble Truth, inspired in Gian Lorenzo by what for him had been (and probably really was) the arbitrary judgment of another pontiff.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.