This contribution is dedicated to the analysis of Caravaggio ’s Medusa and the effects this work had on the art world. In order to put more emphasis on this painting, which represents a fundamental turning point in his painting, and to endow it with additional value, we wanted to extend the study also to the sources, both intellectual and iconographic, that enabled Caravaggio to create a work of such great importance for the history of art. To this end, we will try to make evident those interweavings between different disciplines (literature, philosophy, art criticism) that represent the different roots that, intertwining, allowed the creation of this painting. This ended up endowing the research also with an additional value: in fact, the reader will thus be put in a position to observe how images, starting from their origin, make a journey that crosses centuries, fashions, and forms of thought, often assuming different values. In this way we will be able to verify how ideas move through time passing freely from one author to another, from one geographical area to another, partially changing appearance and sometimes even meaning depending on the personalities responsible for the different contributions, thus finally showing all the complexity of a plot that would otherwise remain hidden.

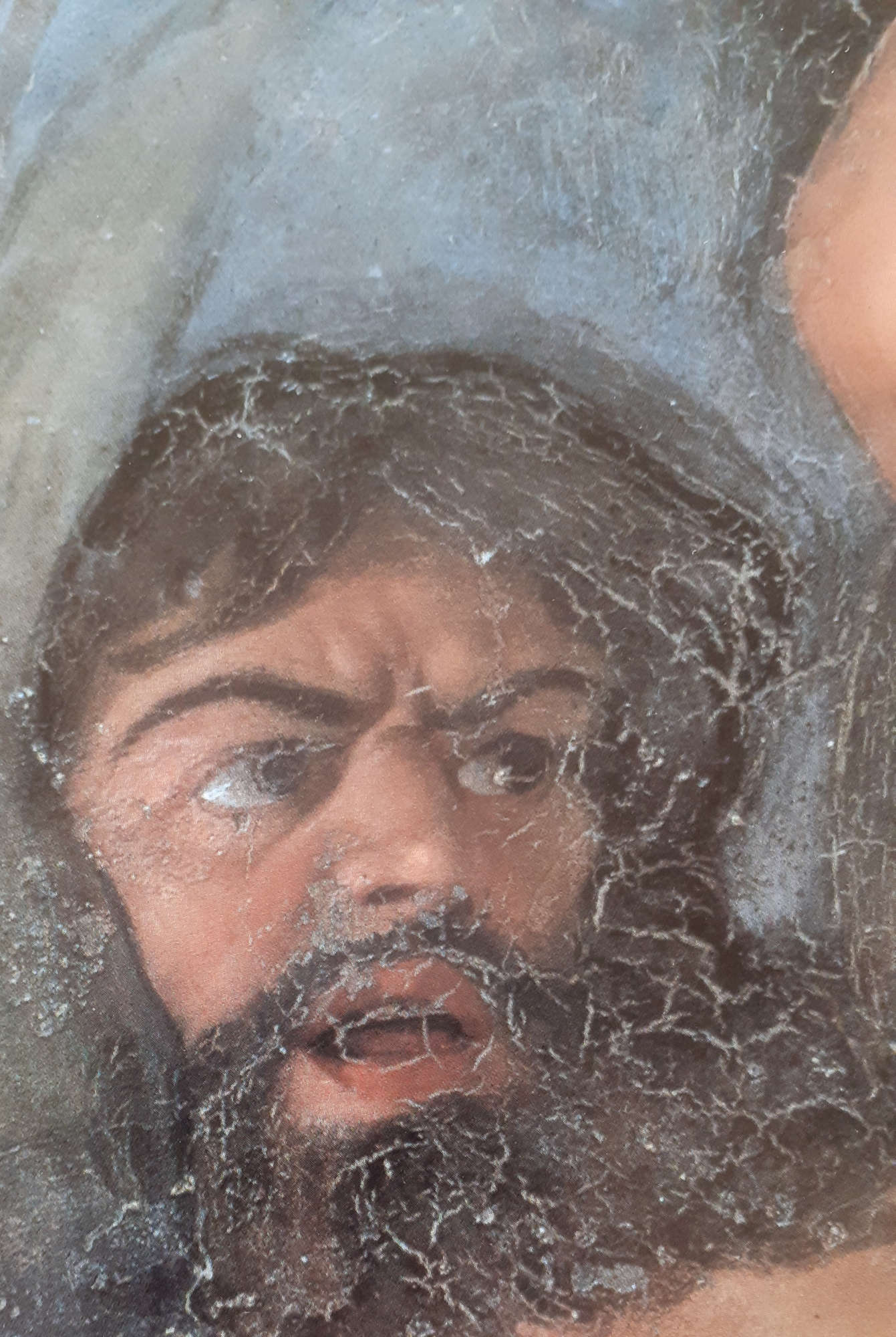

The Medusa (fig. 1) is a decisive junction for the fate of Caravaggio’s art; in fact, because of the ferocity and rawness of the subject, this painting represents a break with the sensibility that characterized his earlier paintings. The power of this innovation will not be destined to be restricted only to the sphere of his work: this painting will have relevant repercussions for the entire history of aesthetics, since its violence coupled with its intense realism broke and definitively shattered those rules on decorum and the balance of pictorial composition that were the object of constant research and became the rule followed by all the masters of the Renaissance. It will be destined to introduce that change in taste that will definitively take shape during the Baroque era; it will be a milestone destined to transform the concept of painting, which from now on will no longer have the purpose of representing the beautiful as was the case in the Renaissance: from now on art will propose to amaze, to strike the viewer’s soul by any means, even the most repellent or strange. This new aesthetics will not scruple to use even the instrument of horror in order to achieve its goal, because “of the poet is the fin la meraviglia”: this verse by Marino renders well the essence of the new spirit, and even in our days we can see how true this assumption still is.

Michelangelo, in addition to being a great painter and sculptor, was also a great draughtsman, and his graphic inventions were widely circulated.Among the subjects that enjoyed the greatest fortune were a group of drawings that he gave to one of his friends, the Roman gentleman Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, father of the important musician Emilio de’ Cavalieri: these are the Supplizio di Tizio, the Ratto di Ganimede, the Caduta di Fetonte and a Bacchanal of putti, to which although there is no certain evidence some authors add, because of symbolic affinities, a drawing depicting a Dream. A leading iconology scholar, Erwin Panofsky, advanced the proposal that two of these images should be read together, as he guessed that their meaning was related to the neo-Platonic culture prevalent in Florence in the 15th century. These two drawings, which were created in about 1533, are endowed with a singular fascination that derives from their allegorical character: they are the Supplizio di Tizio (fig. 2), a titan who attempted to rape Latona, and the Ratto di Ganimende (fig. 3), which depicts the abduction of the young boy by Jupiter transformed into an Aquila.

According to his indications the drawing of Titius tormented by the vulture eating his liver stands for the torment of the lover torn by sensual passion, as in fact is described by Bembo in the Asolani (1505) and also later by Ripa (1593) in the image of Tormento d’amore. Of opposite significance, on the other hand, is the abduction of Ganymede, which is meant to represent the rejection of earthly desires.Panofsky connects this drawing to Landino ’s Commentary on the Divine Comedy, in which case the eagle that abducts him is the symbol of divine Charity while Ganymede represents the human mind that is abducted by the divine after it has abandoned earthly passions. Panofsky also relates this drawing to an emblem ofAlciato: That Man Must in God Cheer Him self (Lyon 1551). This sixteenth-century author also interprets the Ganymede as a symbol of the human mind raptured by the divine, and in his French-language commentary (Lyon 1551) he adds that the spirit of man immersed in contemplation is as if he had abandoned the body.

It is appropriate to add to these early indications the fact that the supreme apex of Florentine neo-Platonic philosophy, Marsilio Ficino, also deals specifically and in depth with this aspect, namely, the rapture of man by the divine in an essay devoted to this theme entitled Rapimento di Paolo al terzo cielo (1476) and in Sopra lo Amore (1471). In the Rapture of Paul Ficino makes it clear from the outset that man’s elevation to God is possible only through Divine Charity: to think that one can accomplish this journey on one’s own is to be considered an attitude that is the result of the sin of pride (as is also found in the thought of the Insensati): “No may it please God that in me there should be such superb impiety,that I should ever have said that I had ascended here, for I do not wish in such revelations of myself to glory: all my glory is no other than to the King of glory, God. Therefore, O Marsilius I no ascended, but yes well I was raptured to Heaven. The grave elements of the world, cannot to high things ascend, if from high things they are not elevated; the inhabitants of the earth cannot to the Celestial degrees rise, if the Celestial father first pulls them not.” This is why the image of rapture, a passive act, is used to illustrate this concept, and it is therefore in this light that the image of Ganymede’s rapture should be correctly understood. Ficino, continuing in his discourse, explains that the way of the soul’s ascent to the empyrean (where God resides) is accomplished by means of the Theological Virtues, and finally he ends his essay with the same phrase given in the emblem of the Alciato: “That God is the same content, and for him alone we rejoice, and for him alone we sanctimoniously rejoice.”

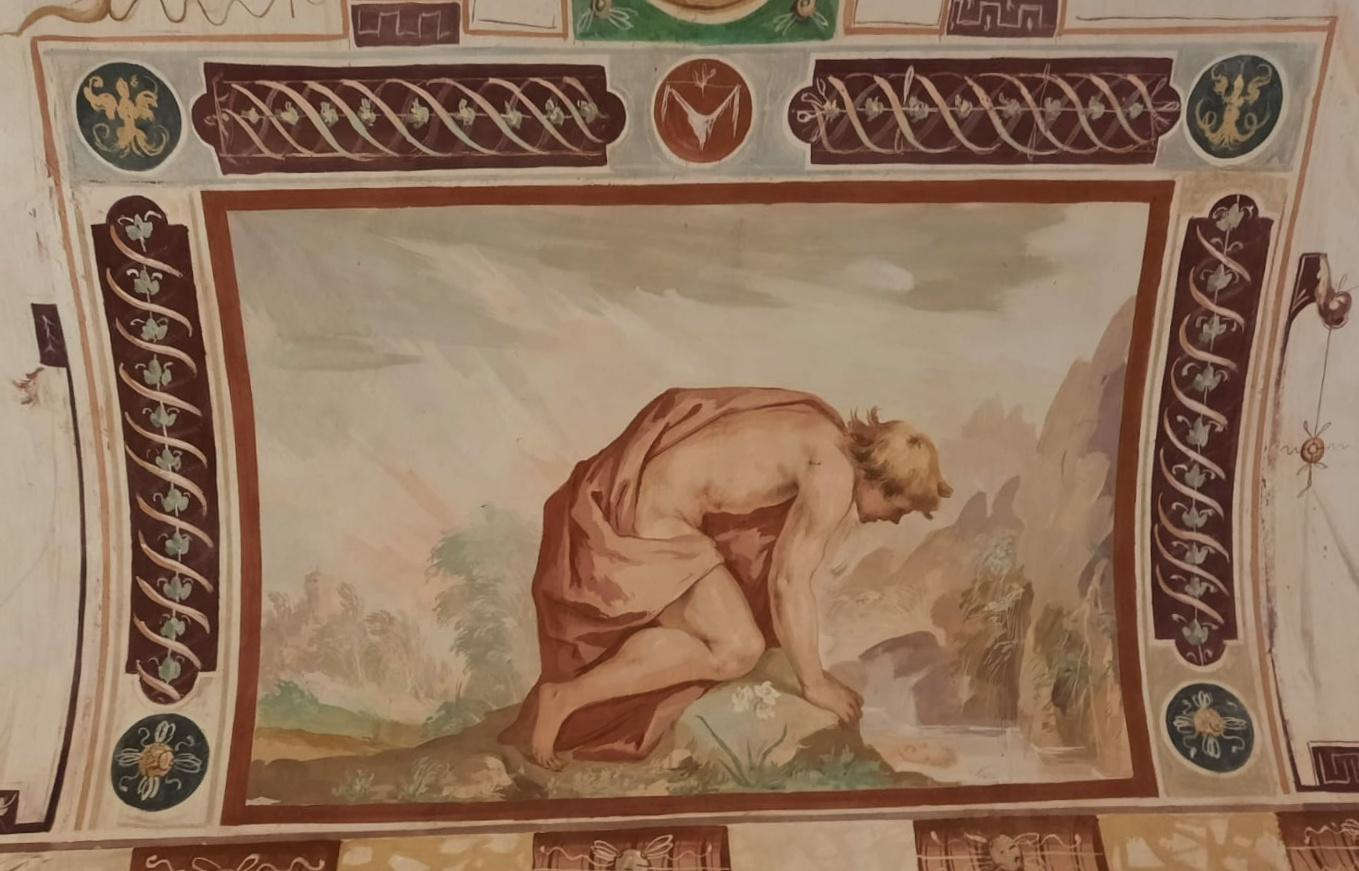

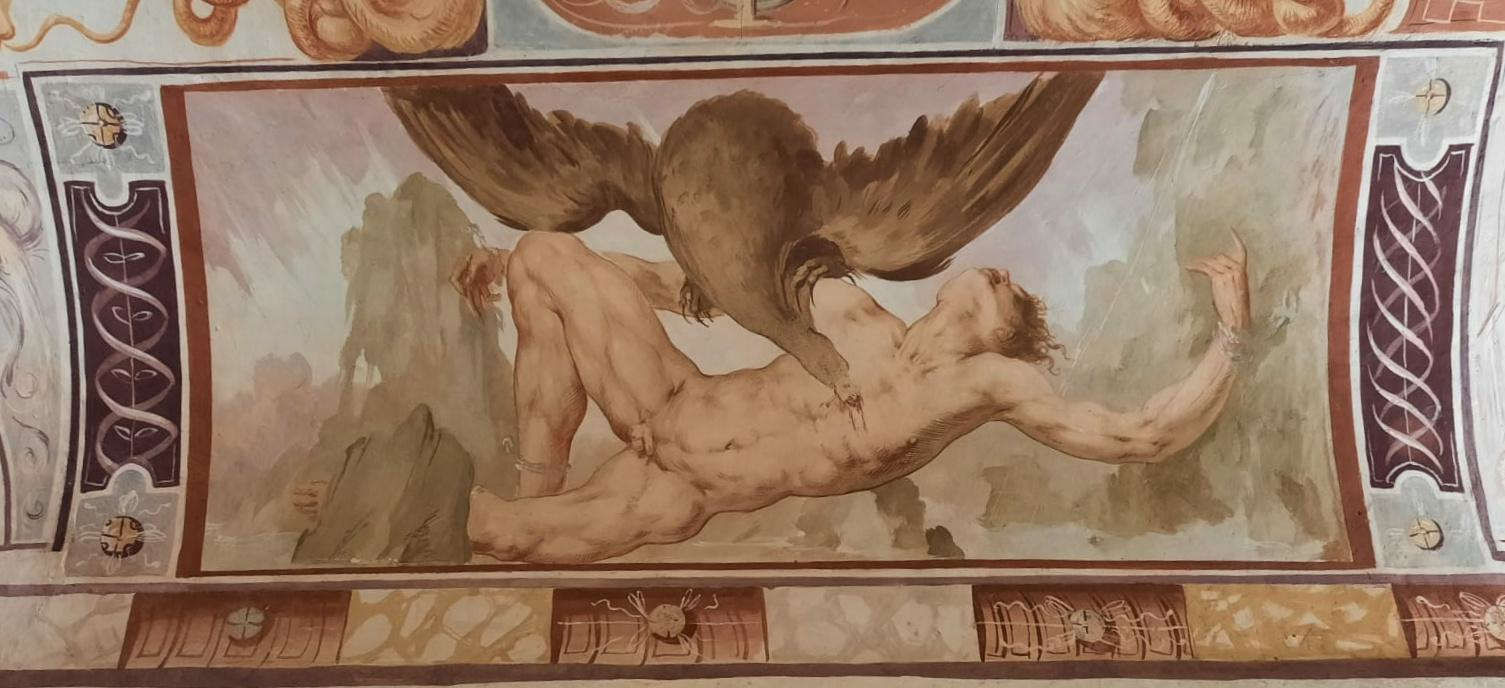

So through this pair of designs, the Titius and the Ganymede, it is intended to represent two different ways of approaching life on the part of man, one guided by the drives of the senses, the other directed toward spiritual needs. Ficino takes up the theme of the two paths, the one to earthly things or to spiritual things in his writing Sopra lo Amore: “Let there therefore be two Venuses in the Soul, the first celestial, the second vulgar: amendue abbino lo Amore: la celeste ha lo Amore a cogitare la divina Bellezza: the vulgare may have Love to generate the same Beauty in the matter of the World” (oration six, chapter VII), and again, “Finally to bring in sum, Venus, is of two reasons: one is that intelligency, which in the Angelic Mind we placed: the other is the power of generating, to the Soul of the World attributed. The one and the other has Love similar, to itself a companion. For the first by natural Love to consider the Beauty of God is enraptured: the second is enraptured again by its Love, to create divine Beauty in worldly bodies. The first first embraces in herself the divine splendor: thence she spreads this to the second Venus... The one and the other Love is honest, following the one and the other divine image”(Oration Two, Chapter VII). Both physical and mental beauty both find root and are generated by divine beauty: this is the true source and ultimate reality of both. The intuition that these two works, which were donated together, have a precise symbolic value and should be read together finds objective confirmation and confirmation in a room in the Palazzo Della Corgna in Castiglione del Lago, whose iconographic program was probably devised by the Insensate Cesare Caporali. In fact, in this very room, which was reserved for the meetings of the Academici Insensati, we find in the frescoes the faithful reproduction (derived from translation prints) of the two Michelangelo drawings we have just seen, Ganymede (fig. 4) and Tizio (fig. 5), and to these are added two more figures: Narcissus (fig. 6) and Prometheus (fig. 7).

The physical distribution decided on for these works assigns each character a different wall; moreover, they are enclosed in differently shaped frames: two are square and two are rectangular. Concretely, we see Narcissus opposed to Ganymede (square frames) and on the other two walls opposite each other we find the punishment of Titius and that of Prometheus (rectangular frames): the latter were two sinners in ancient Hades united by a very similar fate, one being mauled by a vulture and the other by an ’eagle.

Of the significance of Titius and Ganymede we have just discussed above: what is now the significance of the other two figures that have been added? Their significance in this room should again be sought within the framework of Ficino’s Neoplatonic philosophy in continuity with the reading of the other two. In fact, the myth of Narcissus also has a symbolic value that is described by Ficino in the sixth Oration of Sopra lo Amore, in chapters XVI to XI where it is appropriately included in the Discourse of how man rises toward God: "Adolescent Narcissus, that is, the Soul of the reckless and ignorant man, does not look upon his own face: which is understood, that he does not consider his own sustantiality and virtue: but his shadow in the water he follows, and strives to embrace it: that is, he beholds around the Beauty which he sees in the frail, running body, like water, which is shadow of the Soul: he leaves his figure, and the shadow never takes. "

In these chapters, the philosopher begins his reasoning on the subject of spiritual asceticism by clearly listing the steps that are necessary to accomplish this journey: “Therefore from the body to the Soul, from the Soul to the Angel, from the Angel to God we must ascend.” First, therefore, it is necessary to abandon the bodily passions i.e. those of the senses, but this is not enough, it is not enough, in fact it is necessary to eliminate also the passions for intellectual endowments, since both have the same root and that is self-love (whose symbol is Narcissus), and both aim at the exclusive satisfaction of one’s own interests: only if one overcomes both of these barriers then one has completely left behind earthly passions. The beauty for which we yearn and which our passions actually desire must be recognized and rediscovered for what it is, its true nature residing in divine beauty; one must therefore not love the beauty of creatures but through the beauty of these come to desire divine beauty: “Therefore the source of all Beauty is God. God is the source of all Love.” Narcissus then represents in this context the man who beginning his life’s journey is attracted to beauty, which can be either intellectual or physical; he imagines that by attaining it he will obtain happiness, but once achieved he realizes bitterly that this does not happen and his need remains unsatisfied. The fresco in the center of the room’s ceiling also deals with this theme: at the top is depicted the myth of Diana and Callisto, which tells how Diana seeing Callisto while bathing naked came to discover that she was pregnant, something that her clothes evidently concealed, and this alludes to the fact that the naked truth is concealed beneath the appearance of forms and only by eliminating these can the most intimate reality be reached. Ficino thus explains the mechanism that imprisons Narcissus: “Friend how much is he however that which thou lovest? Ella is a surface outside: nay, it is a little color, that which enraptures you: nay, it is a certain very slight reflection of lights and shadows. And perhaps more anon a vain imagination dazzles thee: so that thou lovest what thou dreamest more anon than what thou seest.”

What Ficino has enunciated here is a concept that will become fundamental in the Baroque era, indeed a mainstay of it (“Life is a dream”), and our choices are often the fruit of our imagination. The philosopher in this passage reflects on the fact that very often we are attracted by the appearances of earthly objects, which can have both a material consistency such as wealth or beauty, but can also have a more abstract nature as in the case of power, of fame: these are the objects of our desire and we attribute to them an importance that in reality, in concrete terms, they ultimately do not have. We imagine that the things we desire will be able to satisfy our innermost needs and so we charge them with unreasonable power, but once we achieve them we find that they are unable to meet our expectations and therefore do not have the value that we had arbitrarily ascribed to them: the final bitter truth is that what we pursued were nothing more than our dreams, our imagination, that is, the reflection of ourselves, a truth of which Cardinal Maffeo Barberini is fully aware and which is reflected in his works. Therefore, by overcoming the first step/obstacle which is represented by getting trapped in the search for bodily beauty, one then runs the risk of falling into the second pitfall, namely, desiring and stopping at the beauty of the soul in its various aspects and that is, wanting to attain the beauty of moral virtues or intellectual virtues, but this search too will lead nowhere and will leave the seeker unsatisfied: “Plato declares in this oration, the beauty of the soul in truth and Wisdom consist: and that of God to men grant. One and the same truth given to us by God for various effects, various names of virtue acquires...Hence two generations of virtues are anovertwo, that is, moral and intellectual virtues: which are nobler, than the moral: the intellectual are Wisdom, Science, and Prudence; The moral, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance” (from Above Love). Even the virtues of the Soul, while having a positive character, constitute but one of the steps to finally arrive at the contemplation of the ultimate Virtue, only a step that serves to reach the Heavenly Virtue which is the divine Virtue in which the unity of creation resides, a concept that is also fundamental in the researches of the Academic Insensates. Having finally left behind also the desire for the beauty of the Soul, according to Ficino one comes to pursue the beauty of the Angel and then finally that Divine: “however, it is necessary that the said angelic light should come forth from a principle of the Universe, which it Unity is called: The light therefore of it Unity in everything most simple is infinite Beauty...infinite pulchritude, infinite Love requires. For which I beseech thee, my Socrates, that thou love creatures with certain manner and term: But the Creator loves with infinite Love: Et guard thyself as much as thou canst that in Loving God thou hast neither manner nor measure at all.”

It follows from this discourse on the elevation of the soul to its higher degrees that the figure of Narcissus represents the initial degree of a path fraught with obstacles, and its symbolic value that we have just explained is confirmed both byAlciati’s text, where Narcissus is the emblem of Philautia (self-love: in his commentary he warns that self-satisfaction is the root of the destruction of the mind), and the same thing happens in Ripa ’s Iconology for whom Narcissus is theLove of Self. The first main problem faced by those who want to embark on the path of ascent is thus precisely that of getting trapped in self-love, that is, getting stuck in the forms of satisfying one’s own pleasure, which can be of two kinds, either physical or intellectual. In the first case it means to remain anchored to bodily pleasures and thus to the lowest stage of evolution: this kind of imprisonment involves the continual search for one’s physical satisfaction without ever finding true fulfillment, so one is condemned to wander from one pleasure to ’another without pause. This fate is represented by Titius who suffers Jupiter’s punishment for seeking erotic pleasure, for which he was chained to a rock with a vulture that eats his liver, which has the property of reconstituting itself according to the lunar cycle. His torment thus continually renews itself, just as the need for new physical pleasures never dies out.

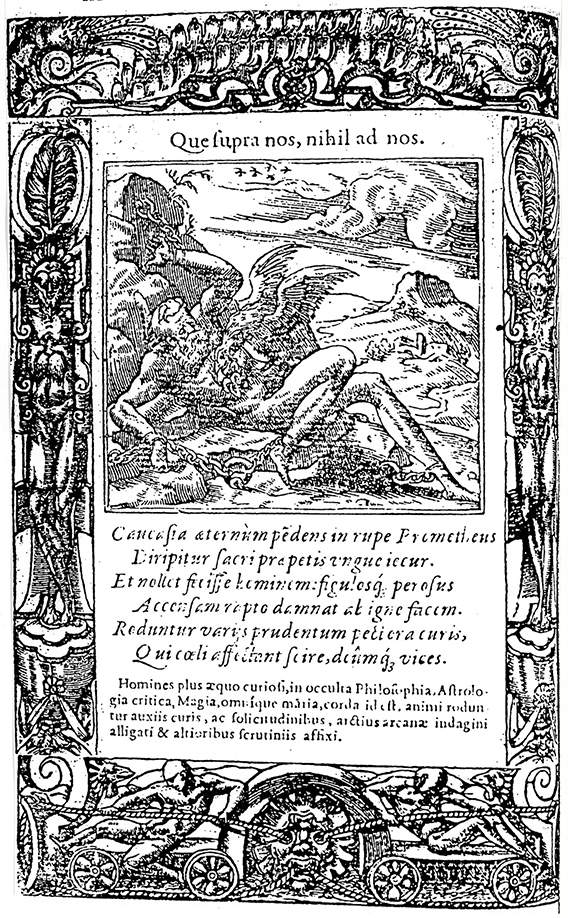

The other kind of error is the one made by the man who has overcome the obstacle of bodily needs but then unfortunately ends up clinging to the pleasure of intellectual abilities, through which he thinks he can independently attain the contemplation of Divinity. As we have already seen this is impossible: this step cannot take place except by means of Grace (it is a rapture not an ascent by one’s own legs), which is why man remains imprisoned in the forms of the beauty of his own soul and does not continue further. This second type of error (similar to the first) is symbolically represented by the myth of Prometheus who suffered a similar fate to Titius: he too was chained to a cliff and an eagle that eats his liver that continually grows back, it is symbolic of a thirst for knowledge that is never quenched. The value of Prometheus is also described by Ficino in his Letters: he is the one who, having tasted a particle of divinity, is condemned to the continual search for the bliss he has experienced, but this need can never be satisfied except by divine intervention: “Such seems to be that most unhappy one who, having conquered the heavenly fire, that is, reason, instructed by the divine wisdom of Pallas, for this very reason stands on the summit of the mountain, that is, in the stronghold of contemplation, because of the continual bites of the greedy eagle, that is by the stimulus of the quest, is rightly judged the most unhappy of men, until he is led to that place from which he had once subtracted the fire, to be pervaded by the totality of light, just as now by a single meager ray he is stimulated toward the totality of divine light.”

This allegorical interpretation is also confirmed in Alciati’s text, which uses Prometheus (fig. 8) as a symbol of the man who wants to push himself too high in the knowledge of things and of God (exactly as Ficino explains): “That which, which is; above us, does not belong to us: Bound with most steadfast chain/Over Caucasus each hor Prometheus lies;/Where with eternal sorrow robs him/The heart ever ever a rapacious Eagle. /So of lofty thoughts the mind full /Solely to be surrendered without ever having peace/Of him who to know too much burns in desire /Siocco; and to regard in the bosom to God.”

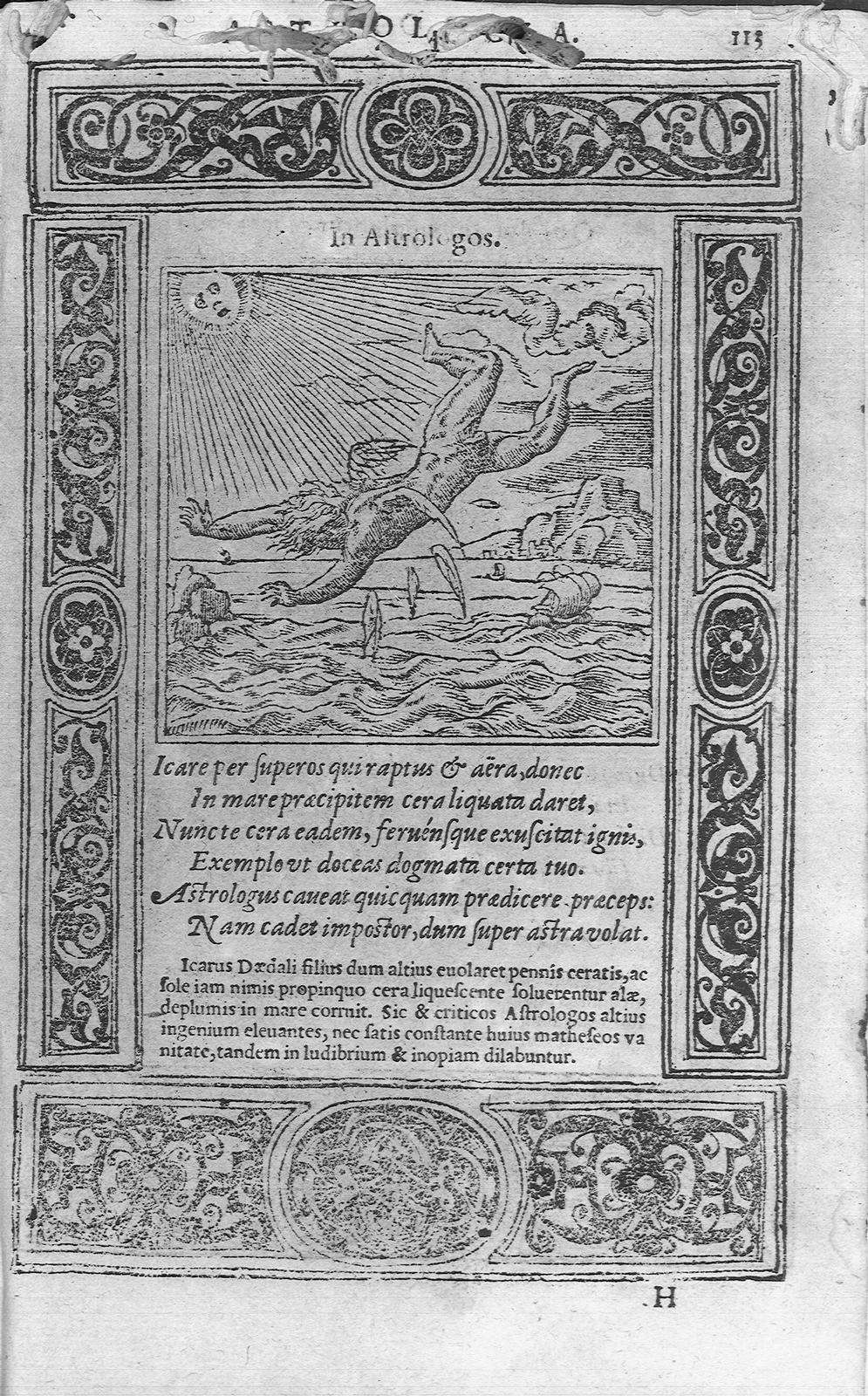

At this point we have completed the symbolic reading of all the four images contained in the hall of Palazzo Della Corgna, and we move on to analyze the third drawing by Michelangelo that was given to Cavalieri, and which illustrates the myth of Phaeton (fig. 9), the son of Apollo who wanted to reach the highest spheres and drive the chariot of the sun, but was electrocuted by Zeus.

The legend of Phaethon also returns precisely in Ficino’s philosophy, and is reported in another of his letters, which is explicitly linked to Paul’s Rapture (where it deals with the symbolic value of the rapture of Ganymede). In this letter addressed to Lorenzo the Magnificent, he reflects on the philosophical speculations made in Paul’s Rapture and admits that he has fallen into the second type of sin we have mentioned, that of intellectual pride, since he wanted to go too far in trying to understand things above his own possibilities as Phaeton did, and therefore was punished with blindness. The significance of the Michelangelo drawing with Phaeton is thus quite similar to the symbolic value of Prometheus. Michelangelo’s three drawings given to Cavalieri thus illustrate the path of a man in love with sensual pleasure (Titius), the path of a man in love with intellectual pleasure (Phaethon), and finally-through the rape of Ganymede-the correct path of man, that of humility and love for the divine, in a manner quite similar to what happens in the Castiglione del Lago frescoes.

There is also to be noted that in the frescoes of the palace the Michelangeloesque image of Phaeton (fig. 10) returns punctually; in fact in another room of the palace this image was taken from Michelangelo’s drawing (fig. 9), and the room is called precisely “of Phaeton” and is part of a group of rooms frescoed by Pomarancio with the collaboration of Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi, a painter of whom we shall speak more later.

Probably someone among the Insensati must have been aware of the symbolic value of all these images and also of their connection with Neoplatonic philosophy: this knowledge may have come within the circle through Aurelio Orsi, who was part of the Farnese court that had also been frequented by Michelangelo during his stay in Rome. Alciati, to explain the same moral of Phaeton uses a very similar myth, that of Icarus (fig. 11) who went too high as precisely Apollo’s son also did and ended up falling.

To summarize now the full meaning of the figures in the room, Narcissus represents the lowest rung of the human condition, when one has the perception of an unfulfilled need and thinks that the satisfaction of this innate need consists in the fulfillment of one’s desires. He therefore chases after the fascination of material things like Titius or the love of intellectual gifts like Prometheus . Titius and Prometheus are actually similar, in fact both pursue a selfish end, both aim at satisfying their egos, and for this reason they try to satisfy it by running after their mirages, their dreams; these kinds of men lack the most important endowment, the basic requirement for hoping to fill that void they can never fill, namelyHumility. Only the path of Ganymede is the perfect condition, which enables one to attain the knowledge of divinity through Divine Grace, which he seeks in all ways with humility and effort; this means that he who in a non-selfish manner goes in search of something other than himself, which in the end precisely because of this quality will be granted to him, represents the exact opposite to Narcissus who stands on the opposite wall and who symbolizes instead the man who is focused only on himself: On his own sensual pleasure or his own intelligence. The middle walls with the torment of the two sinners, on the other hand, represent the punishments for those who take a wrong path; only those who follow Ganymede’s virtuous path will be rewarded.

The two additional figures that have been introduced into the Castiglione del Lago room, Prometheus and Narcissus, thus represent on the level of meaning a corollary to the cycle conceived by Michelangelo in his drawings given to Cavalieri. In fact, the same pattern is reflected in Michelangelo’s three drawings, where Titius represents the man imprisoned in bodily desires, Phaeton the one who is trapped in intellectual desires, and Ganymede instead the correct path.

Ficinian neo-Platonic philosophy undoubtedly represents a privileged interpretive point for reading all these works, because it understands and provides the unifying key. Narcissus, Ganymede, Prometheus, Phaeton, are all symbolic images that have a definite value in Ficino’s thought, and among other things they all serve him to explain the same thing, the process of asceticism toward the divine. Added to this first fundamental evidence are Alciato’s explanations that provide the same interpretations of these myths and thus another independent humanistic source confirms at the level of symbolic tradition the significance of Prometheus, Ganymede, Narcissus, and Icarus. Last but not least, there is the fact that this interpretation of the images in the hall is to be considered correct because, as we have seen, it is entirely consistent with the ideas of the academics, who precisely gathered there. After all, the Insensati are perfectly aware that the type of their research unites them with Platonic philosophy, as Massini declares in his Lezioni Accademiche (one of its founders had even chosen the nickname Platoni), while Dionigi Crispolti, brother of Cesare, the prince of the Academy, in his dissertation on the enterprise of Paolo Mancini writes that he “hopes, by means of the essercitii of this most noble academy, to revive in himself that virtue” which failed when the “soul was infused into his body,” and Bovarini in his lecture On Shame refers back to the contents of the Phaedrus. It is therefore entirely consistent to use these symbolic images in the decoration of their hall.

Finally, there is one last drawing by Michelangelo, which can also be linked to those given to Cavalieri, that deserves our attention and is called Il sogno (fig. 12), from a definition by Vasari: here we see an angelic figure descending from heaven to awaken a sleeping man surrounded by various other tumultuous figures, which are to be interpreted as the object of his dreams, of his imaginations. The traditional meaning of the work has been handed down by Hieronymus Tetius(Aedes Barberinae ad Quirinalem Descriptae, 1642), who in his description of the Barberini palaces defines this invention as an allegory of the human mind awakening to Virtue from the sleep into which vice had plunged him. The protagonist is surrounded by representations of the seven deadly vices that trap him in these desires for imaginary goods and happiness, he is leaning on a sphere representing the world, and below him we see masks that are again representative of deception. This interpretation can be superimposed on the passage from Ficino that we have just analyzed above, “And perhaps more tosto a vain imagination dazzles you: so that you love what you dream more tosto than what you see.” His earthly desires are actually nothing more than images of his dreams, leading him to nothingness. Therefore, this drawing depicting the Dream must also be interpreted as an accompaniment and completion of the neo-Platonic type of discourse begun by Michelangelo with the other three drawings given to Cavalieri: man, in order to arrive at truth and happiness, must abandon all the illusions he has fabricated for himself, whether sensual or intellectual.

Michelangelo’s drawings soon became very famous and their images were widely circulated through prints: for this reason their examples were taken up and assimilated in the works of numerous later artists, and among them was Titian Vecellio, who, in the mid-sixteenth century, produced an important cycle of paintings for the Spanish crown, consisting of four large canvases depicting the punishments inflicted on the sinners of ancient ade: Titius (fig. 13), Sisyphus (fig. 14), Tantalus, and Ission. Their mythological figures are handed down in Ovid’s Metamorphoses : in this text for the first time we find all four of these transgressors gathered together.

Of the paintings made by Titian, unfortunately we are left with only Titius and Sisyphus, since Issione and Tantalus were destroyed in a fire; however, of Tantalus we know at least the iconography through an engraving made by Giulio Sanuto (fig. 15), of Issione, on the other hand, not even that, since we are not aware of a print directly referable to this painting. The cycle was commissioned by Mary of Habsburg in 1548 to commemorate her brother Charles V’s military success over the League of Smalcalda and was intended to embellish her royal palace at Binche in Belgium, a land that was then under Spanish rule: the four canvases adorned the residence’s reception hall.

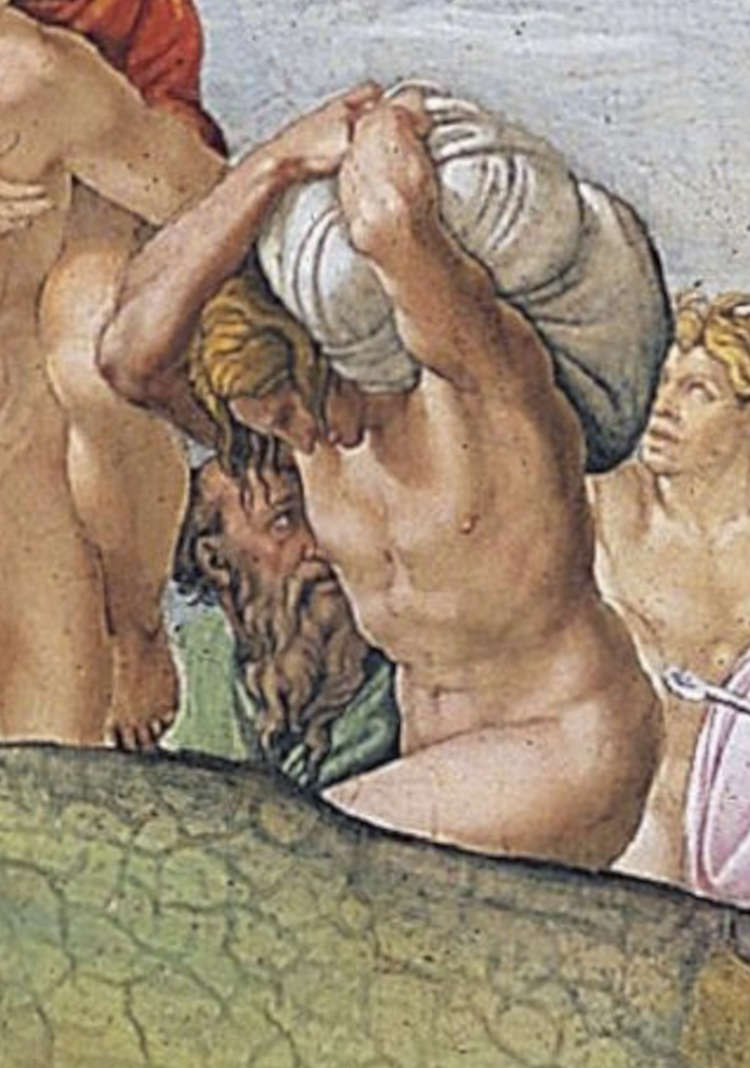

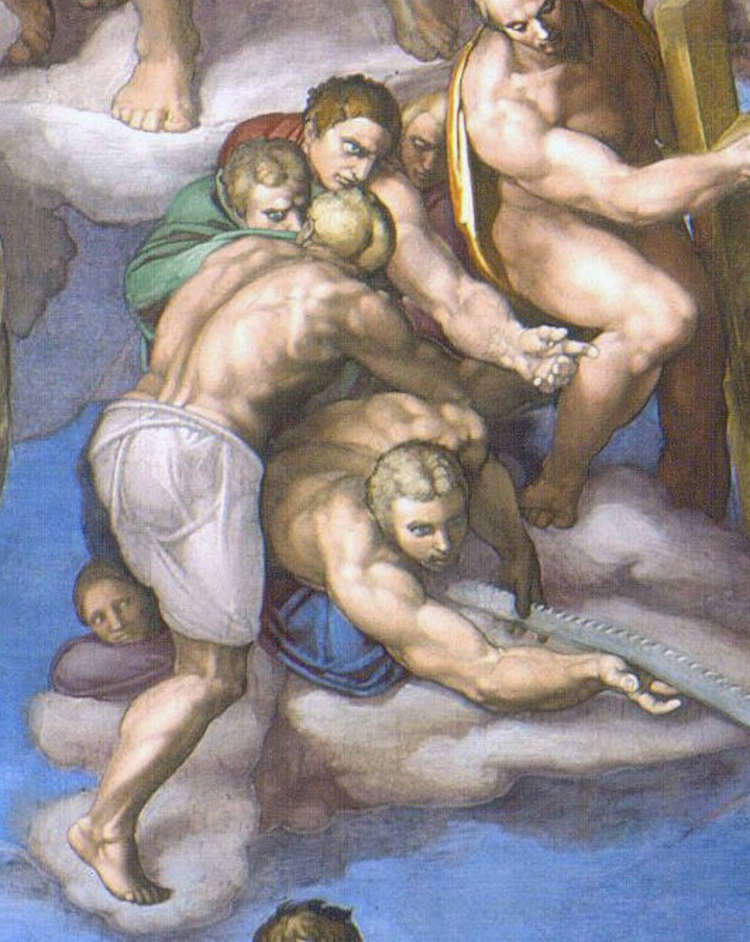

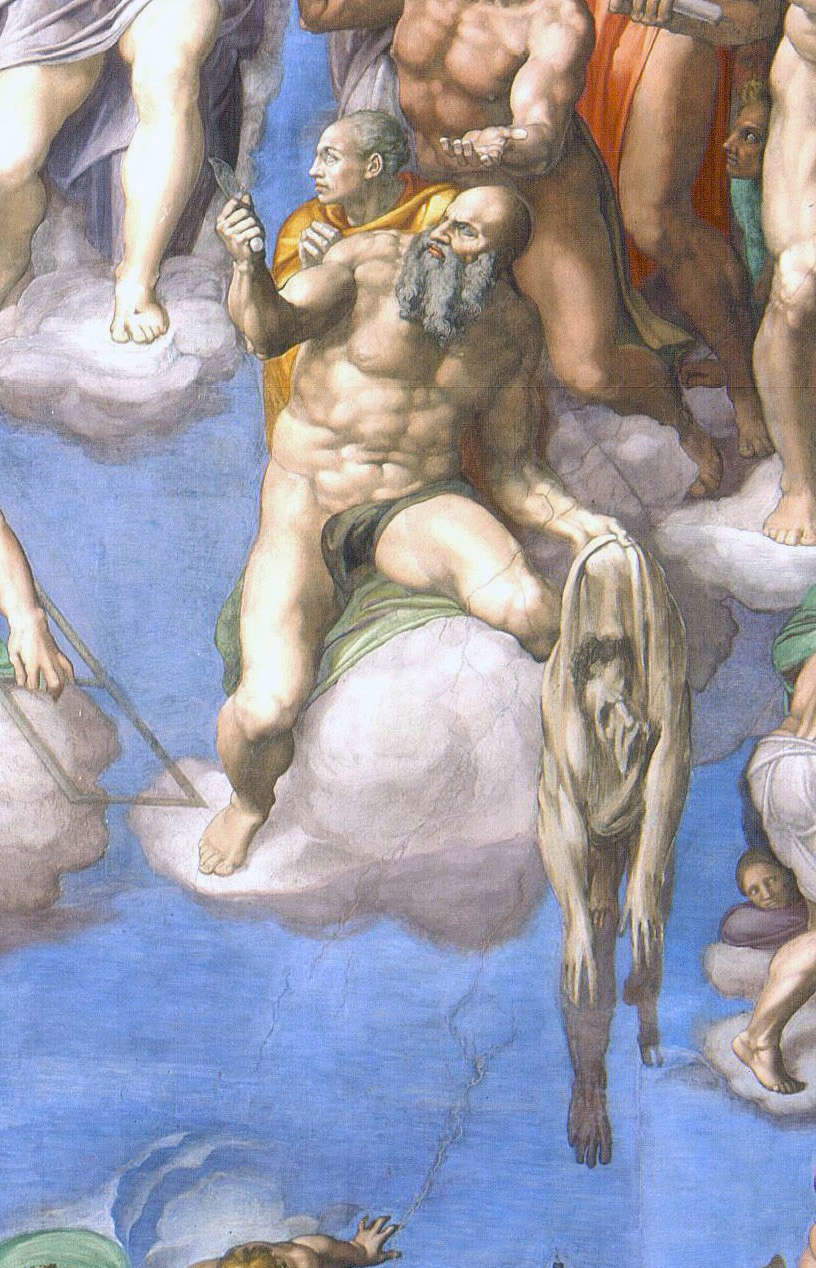

From an iconographic point of view, the images devised by Titian show that he was familiar with the figures painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel; the Cadore artist certainly had the opportunity to see them during his stay in Rome, and contemporaries had also noticed this connection; in fact, as early as 1571 Giovanni Battista Venturino da Fabriano noted the artistic proximity of Titian’s canvases to the figures frescoed in the Vatican Chapel. This relationship is also confirmed in more recent times by a Titian scholar, Paul Joannides, who likens the figure of Sisyphus (fig. 14) to a figure carrying a burden in the Universal Deluge (fig. 16); in addition to this this other figure belonging to the Judgment (fig. 17) should also be taken into account as a model for Sisyphus, while the upper part of Tantalus (fig. 15) resembles that of St. Bartholomew present in Michelangelo’s Judgment (fig. 18).

In the drawing of the Punishment of Titius of 1532 (fig. 2) given by Buonarroti to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri we then have another sure reference for the figure of Titius painted by Vecellio (fig. 13): knowledge of Michelangelo’s fresco of the Martyrdom of St. Peter in the Pauline Chapel most likely also contributed to its conception, its workmanship in fact dating to the very years of Titian’s stay in Rome, between 1545 and 1546 (fig. 19). Finally, it should be added that the allegorical meaning of the sufferings caused by sensual love, which we have discussed above with regard to Michelangelo’s drawings (Bembo), in the sphere of Spanish literature soon extended to Titian’s paintings as well. An early reflection of the symbolic meaning related to these images can be found in the literary works of Lope de Vega, Juan de Jaurengui, and especially in the works of Miguel de Cervantes (fig. 20), who absorbs this allegorical value in both the first part of Don Quixote and Galatea.

Cervantes resided permanently in Italy beginning in 1569, and in 1571 he took part as a soldier in the Battle of Lepanto in the service of Marcantonio Colonna: he certainly had excellent relations with this noble family since he dedicated to Cardinal Ascanio Colonna, the brother of the marquise Costanza, the very Galatea (1582). Miguel de Cervantes was also a friend of Marquis Ascanio I della Corgna, the owner of the palace in Castiglione del Lago , whom he met during the Battle of Lepanto, but above all he befriended the poet Cesare Caporali, the senseless academic who helped create the cycle of frescoes in Castiglione del Lago. So it is probably no coincidence that Cervantes’ Galatea contains the theme of the transience of earthly pleasure and the disillusionment of love, themes typical of the Insensati, a meaning also found in the Castiglione frescoes. The Perugian poet Caporali therefore, on balance, proves to be a leading figure because of his ability to interweave relationships with important poets of his time, and he was evidently held in high esteem in artistic-poetic terms as well, as inferred from the encomiastic words dedicated to him by Giovanni Lomazzo. Even Cervantes was inspired by one of Caporali’s poems, the Journey of Parnassus, for his eponymous Viage del Parnaso, where he makes express reference to the very person of Caporali.

The Spaniard was certainly no stranger to the ironic spirit of the Perugian and possessed copies of his texts in his personal library; moreover, he was intimately familiar with Bembo’s Asolani where, as we have seen, the figure of Titius takes on the symbolic value of the sufferings of love; thus it may have been Cervantes, the elder among the Spanish poets we have just mentioned, who spread this allegorical meaning in Spain. But it was in the Netherlands, namely in the place where they were originally preserved, that Titian’s works found the widest echo from the iconographic point of view: many Dutch artists in fact painted, drew and engraved themes derived from the Titian cycle, and in some cases they were even pupils of the Cadore, as was the case with Cornelis Cort and Dirk Barendsz. The cycle found a very favorable reception, especially among the artists of the Harleem school, among whom the figure of Hendrick Goltzius undoubtedly stands out, who executed his own painted version of the Titius (1618) clearly inspired by Titian’s painting and above all engraved by burin, a technique in which he was an absolute master, some works derived from the cycle. In 1577 he made a print with the infernal punishments (fig. 21) that is quite important for our discussion, in fact inside it all four images of Titian’s sinners are represented, so this print also allows us to reconstruct the appearance of the lost Issione. In the foreground in its central part we can see the same pose of Sisyphus, on the left we see Titius, while on the right is Tantalus, and finally always in the foreground in the upper part we find depicted a sinner held upside down that must forcibly reflect the lost figure of Issione.

Since in this print the figurations of the three sinners whose image we know are faithfully adhered to Titian’s original images, it follows thatIssione must also be so, of whom through this engraving we finally have a concrete indication of the Iconography. This hypothesis is also confirmed by the proximity of the pose of this figure to the work of the same subject made by Ribera (fig. 22), who studied “the Furies” very carefully, since they were transferred to Madrid in 1566. As further proof of this identification we can note that, as was the case with the other figures in Titian’s cycle, it too originates from Michelangelo’s inventions, particularly this Last Judgment group (fig. 23), with a figure upside down, held by the knees and arms crossed above the head.

Goltzius, in 1588, produced a further series of four engravings inspired by Titian’s cycle, again having for subject matter four sinners from ancient myth(Issione, Tantalus, Phaeton, Icarus), which Caravaggio certainly had occasion to see. These etchings were a considerable success and are still among his most appreciated works today. A few years later, in 1590, he stayed in Italy where he stayed until 1591, and during his tour he went to Rome, where he studied the works of Michelangelo and Raphael and collaborated with the painter Gaspare Celio.

Beginning at the end of the 16th century, Titian’s cycle of paintings began to be called in Spain by the appellation “Las Furias,” and the reception hall where they were kept was also so named: “Sala de las Furias.” This happened apparently without any understandable reason since the mythological figures of the sinners have no bearing on the Furies of Greek mythology. In my opinion the reason for this likeness must be found in Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo’s Treatise on the Art of Painting Sculpture and Architecture (1584). In fact in the seventh and last book of this treatise the writer provides models for the images most frequently used by painters. In particular in chapter XXXII, which deals with "Della forma da dare alle tre furie infernali,“ we find indications of the examples to be used here: ”This description of hell that I have summarily gleaned from Dante has followed Buonarrotto and in drawing Taddeo Zuccaro’s brother yes as I said in the other book, and beyond them Titian representing things greater than natural and divinely coloring them as with Prometheus bound to Mount Caucasus, torn by the eagle, Sisyphus carrying a very large stone Titius torn by the vulture, and Tantalus whom he painted to Queen Mary sister of Charles the Fifth, and the unique Leonardo Vinci, who demonstrated the forms of living animals and serpents into wondrous monsters, painting among other things over a wheel the horrid moon face of the infernal furies, which was sent to Ludovico Sforza duke of Milan, double which he then made another which is now in Fiorenza...Thus may they be represented in the tremendous judgment of Christ, as in several other gestures much observed in his Buonarroti, and forms, making in them according to his acts the body with disdainful and proud faces, of which many may be imagined... ".

Lomazzo’s text clearly (and also precisely) indicates that the cycle commissioned by Maria of Habsburg to Titian is to be taken as a reference for realizing the physical attitudes and expressions of the Furies, thus establishing a direct link between these mythological figures and the Titian cycle destined to become their exemplum: in this way Titian’s damned became Las Furias, and the other models proposed for the same purpose by Lomazzo were Leonardo’s two Jellyfish and Michelangelo’s damned depicted in the Last Judgment.

Caravaggio, during his time spent at the residence, of Cardinal del Monte painted both the shield with the Medusa and the fresco with Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto: in the latter case he drew his inspiration from the images of Titian sinners handed down in the printed versions made by Goltzius. Indeed, if we compare the Jupiter of the Ludovisi fresco (fig. 24) with the engraving of Issione, taken as a counterpart (fig. 25), we cannot fail to grasp the certainty of its derivation.

Mina Gregori then not only confirms that Caravaggio took his cue from the cycle made by Goltzius, but also adds the fact that the painter was also familiar with Titian’s original cycle: in fact, in the scholar’s opinion, the eagle of the Titian Titian and the manner in which it clings to his body served as his guide in making the same animal for the figure of Jupiter. Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, too, agrees that Caravaggio was familiar with the Dutchman’s cycle and sees reflections of it in the slightly later Martyrdom of St. Matthew. To try to explain how it was possible for Caravaggio to have become acquainted with these models, we can first note that Goltzius’s prints and models of the Titian cycle circulated within the workshop of Arpino, also we should not forget that Caravaggio was in the workshop of Peterzano who had been a pupil of Titian himself. Instead, for the setting of the other characters in the fresco, Neptune and Pluto, we should rather refer to the examples of the frescoes in vertical perspective painted in San Paolo Converso in Milan by Antonio and Vincenzo Campi, a site where Peterzano had also worked, or to the Mercury frescoed by Camillo Procaccini in the Nymphaeum of Pirro Visconti. We can also add that most probably for the conception of the expression of Neptune (fig. 26) he made use of the invention contained in a very famous Michelangelo drawing, that of a damned soul.

This drawing was given by Michelangelo to Gherardo Perini as a gift and became widely circulated through the many printed translations, eventually becoming the perfectexemplum for the representation of extreme pain. Its most famous reproduction is a period copy preserved in the Uffizi Drawings and Prints Cabinet (fig. 27) that was extensively studied by Berenson, who describes it to us as follows: “Scapigliata head of a damned soul screaming in rage or pain, framed by fluttering cloths like sails buffeted by the wind”: the scholar related it to the Last Judgment, as indeed seems logical for the subject matter, and suggested a juxtaposition with a head of a demon (not a damned one) to the left of Minos’ face (fig. 28), something entirely reasonable, although it seems to me that this graphic evidence is altogether to be approached to the screaming figure, with cloak and hair shaken by the wind (exactly as in the drawing), of a punished sinner (thus a damned soul) frescoed in the Universal Flood in the Sistine Chapel (fig. 29).

It is quite natural to think that Caravaggio was familiar with the iconography of this drawing or more likely had directly seen the character of the Flood in the Sistine Chapel, a place he was very familiar with; the fresco with the gods dates from the period when the interest and study of the screaming heads that appear very often in his compositions of those years was deepest in him. It should be added that this graphic proof is historically known by a different appellation, namely, “the fury”: it too, therefore, was called exactly like Titian’s damned. In fact, this is how it was described in a Medici inventory of the 1660s (prior to Lomazzo’s treatise): “a face almost that of fury.” At this point the question arises as to the origin of this nickname, which in the case of this Michelangelo drawing evidently cannot derive from Lomazzo’s Treatise. Turning our gaze to the manner in which the model of this image spread through engravings, we can see that it was used by Rosso Fiorentino in the making of a drawing of an Infernal Fury later translated into print by Giacomo Caraglio in 1524 (fig. 30).

Hence most likely the Medici inventory, because of the printed translation made by Rosso and Caraglio, makes known for the first time the use of this Michelangelo model relating to the damned of the Judgment for the realization of the figures of the Furies. It was thus the use of Michelangelo’s drawing of the damned soul as a model for the printing of the Fury that gave rise to the tradition of calling the face of the damned devised by Michelangelo “the Fury”; later Lomazzo suggested using all of Michelangelo’s images of the damned as a model for representing the three, and because of the expressive closeness he extended this use to Leonardo’s Medusa and the Titian cycle as well.

Michelangelo was an inescapable touchstone for Caravaggio, and he perhaps also wanted to present himself to the Roman public as the new Michelangelo: his friend and scholar Marzio Milesi composed a poem on this theme, and indeed Michelangelo’s Roman frescoes represented a privileged source of derivation for Caravaggio throughout his career. Following this thread, several scholars - Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Mina Gregori, and Klaus Kruger - have proposed that the drawing with Michelangelo’s fury served to inspire Caravaggio’s Medusa as well; in addition to this example, it is logical to think that the painter must surely have also made use of the similar precedent of the caster with Medusa painted by Leonardo for his conception. We thus enter the concluding part of our discourse, which deals with how Caravaggio also used for his paintings the third and last iconographic model proposed by Lomazzo in his passage on the Furies, after that - as we have seen - he used both Titian’s damned and Michelangelo’s damned. In fact, Caravaggio employed all three examples proposed by Lomazzo in his paintings: therefore, it seems at this point very likely that the painter was perfectly familiar with the Milanese theorist’s passage, since he accepted its suggestions in full. The wheel with the Medusa (fig. 1) by Caravaggio (diameter 55 cm) was in all likelihood commissioned by Cardinal del Monte to make a gift of it to Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici in order to compensate for the loss of the one painted by Leonardo that was part of the Medici collections and had already been lost in 1587. The Caravaggio painting was first inventoried on September 7, 1598, and was probably donated by the Cardinal to the Grand Duke during a long journey with various stops that the cardinal began on April 13, 1598, and which brought it to Florence on July 25, 1598. If, therefore, Caravaggio had the task of measuring himself against Leonardo’s precedent it seems entirely reasonable that he took his cue from it and then produced his own version of the theme with those strong and realistic tints that characterized his “manner.”

Since we do not possess a certain iconography of the Leonardesque image, critics generally believe that an engraving by Cornelis Cort (fig. 31) represents the closest reproduction of the original work and precisely from this it makes the appearance of the Caravaggesque one descend.

From Lomazzo’s testimony, however, we know that Leonardo made not one, but two Medusae, a first one that was preserved in Milan and a second one in Florence, and this account appears to be entirely correct, even in the sequence of execution: in fact, Vasari in his Life of Leonardo, written about fifteen years before the Lombard’s treatise, reports the same news, namely that a first Medusa was given by Leonardo to his father, Ser Piero da Vinci. It was made on a flat fig-wood wheel: “Lionardo, having one day received this wheel in his hands, seeing it twisted, badly worked and clumsy, directed it with fire, and gave it to a turner, of rough and clumsy that it was, he had it reduced delicate and even. And afterwards having plastered and styled it in his own way, he began to think what could be painted on it, that it might frighten those who came against it, representing the same effect as the head already of Medusa.” Piero then resold it to some merchants who in turn resold it to the Duke of Milan: “Appresso vendé ser Piero quella di Lionardo secretamente in Fiorenza a certi mercatanti, cento ducati. Et in breve ella pervenne a le mani del duca di Milano, vendutagli 300 ducati da detto mercatanti.” Leonardo later produced a second work with the subject of the Medusa, which in truth Vasari tells us is a painting and not a caster, kept in the collection of Cosimo I de’ Medici: “Vennegli fantasia di dipignere in un quadro a olio una testa d’una Medusa con una acconciatura in capo con un agrupamento di serpe la più strana e stravagante invenzione che si possa immaginare mai; ma come opera, che portava tempo, e come quasi interviene in tutte le cose sue, rimase imperfetta. This is among the excellent things in the palace of Duke Cosimo.”

At this point what was the appearance of the images painted by Leonardo and which served as an example for Merisi? It seems logical, and most likely, that the painter

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.