Today, Caravaggio ’s Bacchus (Michelangelo Merisi; Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) is one of the most famous paintings in the history of art, one of those for which people purposefully queue to enter the Uffizi. But a little more than a hundred years ago, when Caravaggio’s art was still far from being rediscovered, the Bacchus languished in the storerooms of Via Lambertesca: it was considered an uninteresting work, to the point that the need to exhibit it was not felt. For a long time no one knew anything about this work: it was rediscovered only in 1913, when Matteo Marangoni, inspector of the Uffizi, noticed it during an inspection among the deposits of the museum in Florence, where it appeared with an inventory number that ranked it in the lowest bracket of the works kept at the Uffizi. He realized the quality of the work, studied it, and published it in 1916, believing it to be a copy of Caravaggio (it was in a very precarious state of preservation, which certainly conditioned Marangoni’s judgment), but still reporting Roberto Longhi’s opinion that it was instead an autograph. In the meantime, the work was being restored on the occasion of the exhibition on Italian painting of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries held at Palazzo Pitti in 1922, and in that very same year Marangoni devoted another study to the work, accepting Longhi’s hypothesis: the Caravaggesque autograph later would be unanimously accepted by the scholarly community.

For some time, the work was associated with a “Bacchus with some bunches of different grapes, with great diligence made, but of a somewhat dry manner,” mentioned by Giovanni Baglione in his Lives of painters, sculptors and architects of 1642, designating the work as one of the first painted by the artist, shortly after he left the workshop of Cavalier d’Arpino. Scholars such as Hermann Voss, Lionello Venturi, and Roberto Longhi himself accepted this idea. It was later Denis Mahon who felt that the chronology of the work should be moved a little further forward, pointing out the fact that, in a note in Giulio Mancini’s Considerations on Painting, there was mention of a Bacchus in the collection of Cardinal Scipione Borghese (“Among much does a beautiful Bacchus et was bearded, Borghese holds it.”): this is the Sick Bacchus in the Borghese Gallery, which was among the paintings the cardinal seized from Cavalier d’Arpino in 1607, and it is in all probability to this painting that the passage in Baglione’s Lives also refers. We therefore do not know with certainty the origins of the Bacchus in the Uffizi: however, it is highly probable that it was a painting commissioned around 1598 by Caravaggio’s first major patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, who requested it as a gift to be sent to Ferdinando de’ Medici, since the work was not known in Rome. Del Monte did the same thing for the Medusa, also preserved today in the Uffizi, and it is not certain that the Bacchus was not also another gift for the grand duke. Then there are some scholars, such as Zygmunt WaźbiÅ„ski, Wolfram Pichler and Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, who on the basis of a document certifying in 1618 the purchase of a Bacchus on the Roman market by the Florentine ambassador Cosimo II, believe that the painting bought for the grand duke of Florence was indeed Caravaggio’s Bacchus.

The situation is complicated, however, by the fact that in the Medici inventories the painting is not recorded. Or at least not as a work by Caravaggio. The only identification proposal along these lines is that of Elena Fumagalli, who has suggested juxtaposing Caravaggio’s Bacchus with a “Bacchus” that appears, without the author’s name, in an inventory of the Medici villa at Artimino dating to 1609.A “Bacchus with a cup of wine in his hand crowned with bunches of grapes and pampanus” is then mentioned in the inventory of the Medici Guardaroba of 1620, but also without the author’s name. It is therefore likely that the Bacchus had been hung from the start in a private apartment, from which it would later be removed at an unspecified time to end up ... in storage. The only certainty, then, is that the story of the Bacchus is as exemplary as ever of the poor fortune that, for centuries, Caravaggio’s art enjoyed.

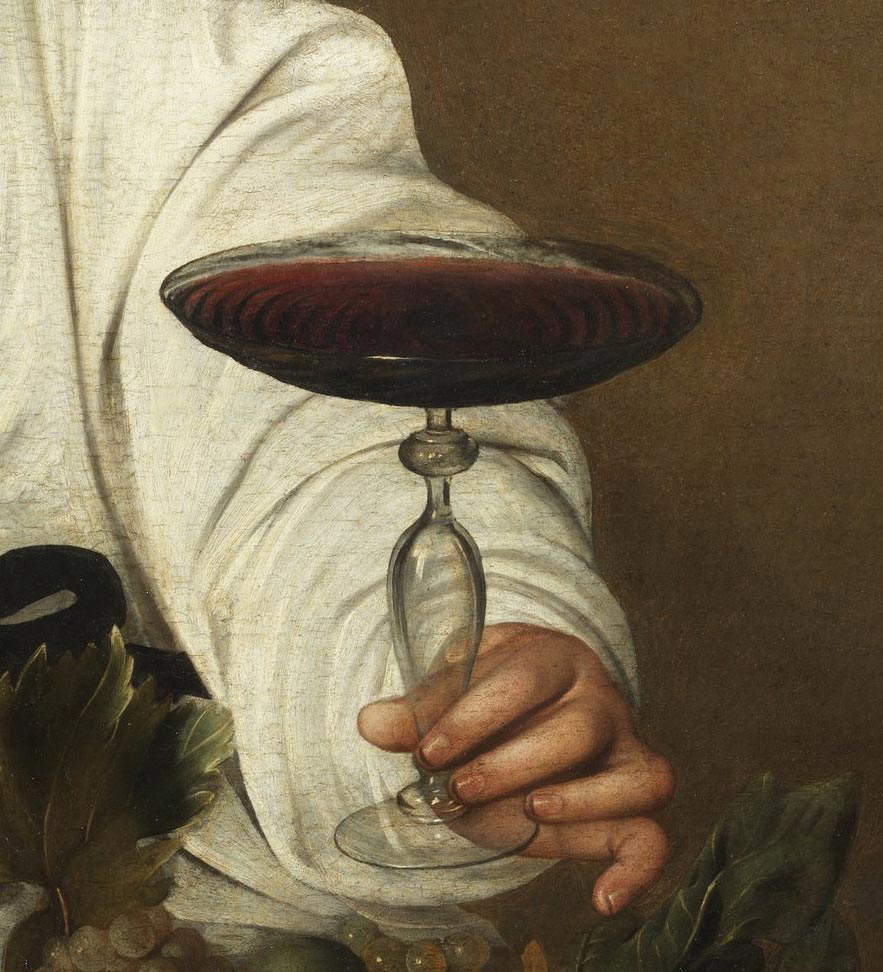

The Bacchus is, therefore, an enigmatic painting, also because of the ways in which the god of wine is depicted, not without a certain sensuality, capable of mixing popular, almost crude elements, and elements instead that refer to the classical tradition. He is presented with a youthful, almost adolescent appearance. Her long black, curly hair is decorated, as per usual iconography, with leaves of life and bunches of grapes. Admirable is the way in which Caravaggio has rendered Bacchus’ expression: from his gaze the weakness typical of one who is intoxicated shines through with all clarity; it seems as if his eyes are lost in emptiness. The muscular body is partly covered by a white linen tunic, the same fabric as the blanket that covers the triclinium on which Bacchus is seated, so much so that it seems that in reality this deity has very little courtly about him: in fact, the blanket allows a glimpse of a striped mattress, and one might think that we are actually observing none other than a boy, sitting on a mattress folded to take the shape of a triclinium, and who has covered himself with the sheet to pretend to have an ancient robe. With his right hand he holds a black bow, while with his left hand he clutches between his thumb, index and middle fingers (looking closely at the fingers one will notice that the young man has dirty fingernails) a wine cup, probably a Venetian chalice: one admires the reflections of light on the glass of the goblet, the gradations of ruby red modulated according to the dimming of the luminosity, and also, at least according to several observers, the flickering of the wine in the goblet, which draws concentric circles perhaps suggesting that Bacchus’ grip is not secure. But as Sybille Ebert-Schifferer has suggested, it is likely that, simply, the lines one sees are grooves etched into the glass. Perhaps, this ambiguity is an effect that Caravaggio himself intended, sought and achieved. On the table in front of the god is a piece of virtuosity, of which Caravaggio had already demonstrated in the celebrated Basket of Fruit now at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan: it is another basket of fruit, a ceramic basket, where we see apples (one of which, the one in the foreground, is half rotten), quinces, a pomegranate, more bunches of grapes, a pear, a peach, figs. Finally, in the left corner, the jug of wine, with still the reflections of light on the glass. And on the surface many have also glimpsed a human face (today hardly visible, but its presence has been confirmed by reflectographic analysis): it is the painter’s self-portrait reflecting on the glass, another piece of virtuosity.

Many interpretations have been suggested for Caravaggio’s work. Carlo Del Bravo has proposed to see in Bacchus an essay in Horatian culture, on the theme of friendship and the “right middle” in pleasures. Fruit would thus be read in relation to Horace’s praise of the frugality of fruit and life according to nature. Kurt Bauch, on the other hand, has spoken generically of a vanitas, with wine and fruit rising as symbols of the fleetingness of pleasures, and the strange black bow, which has nothing to do with the traditional iconography of Bacchus, would thus become an obvious symbol of death. According to Donald Posner, we are instead in the presence of a painting that explicitly and intentionally praiseshomosexuality, since it would depict Caravaggio’s lover caught in his daily routine: however, in order to prevent the work from suffering the obvious condemnations of the case, Michelangelo Merisi would have had the intuition to disguise the young man as Bacchus with what he had (the mattress as a triclinium, the sheet to simulate the toga). On the other hand, the interpretation of a Catholic scholar such as Maurizio Calvesi, who has given a Christological reading of Caravaggio’s Bacchus, is of a completely opposite sign: in particular, the Caravaggesque god would allude to the groom of the Song of Songs, in turn an allegorical image of Christ, and described with images not far from that of Caravaggio’s painting, such as the cup of wine, the black and curly hair, the drunkenness to be understood as intoxication resulting from communion with God, the basket of fruit that becomes a symbol of the Church. The black bow, placed near the navel (a symbol of the center of the world), according to the religious reading should be interpreted as the knot that binds the human being to God. Nothing, however, prohibits one from thinking that the bow is divorced from any symbolism and serves only to hold up the sheet. Again, according to Avigdor Posèq this is still a painting of a homoerotic subject, but approached in a sophisticated way, specifically alluding to Bacchus as a deity described by the ancients as devoted to passion for people of the same sex. Finally, of note is Giacomo Berra ’s recent reading that Caravaggio may have painted his Bacchus in comparison with ancient statuary, thus reviving a theme (that, precisely, of the comparison between the arts) that had fascinated sixteenth-century artists. In particular, the Florentine Bacchus may have been a work to be set against some Antinous-Bacco statue in order to demonstrate the supremacy of painting over sculpture, choosing the very subject of the Antinous-Bacco as the battleground.

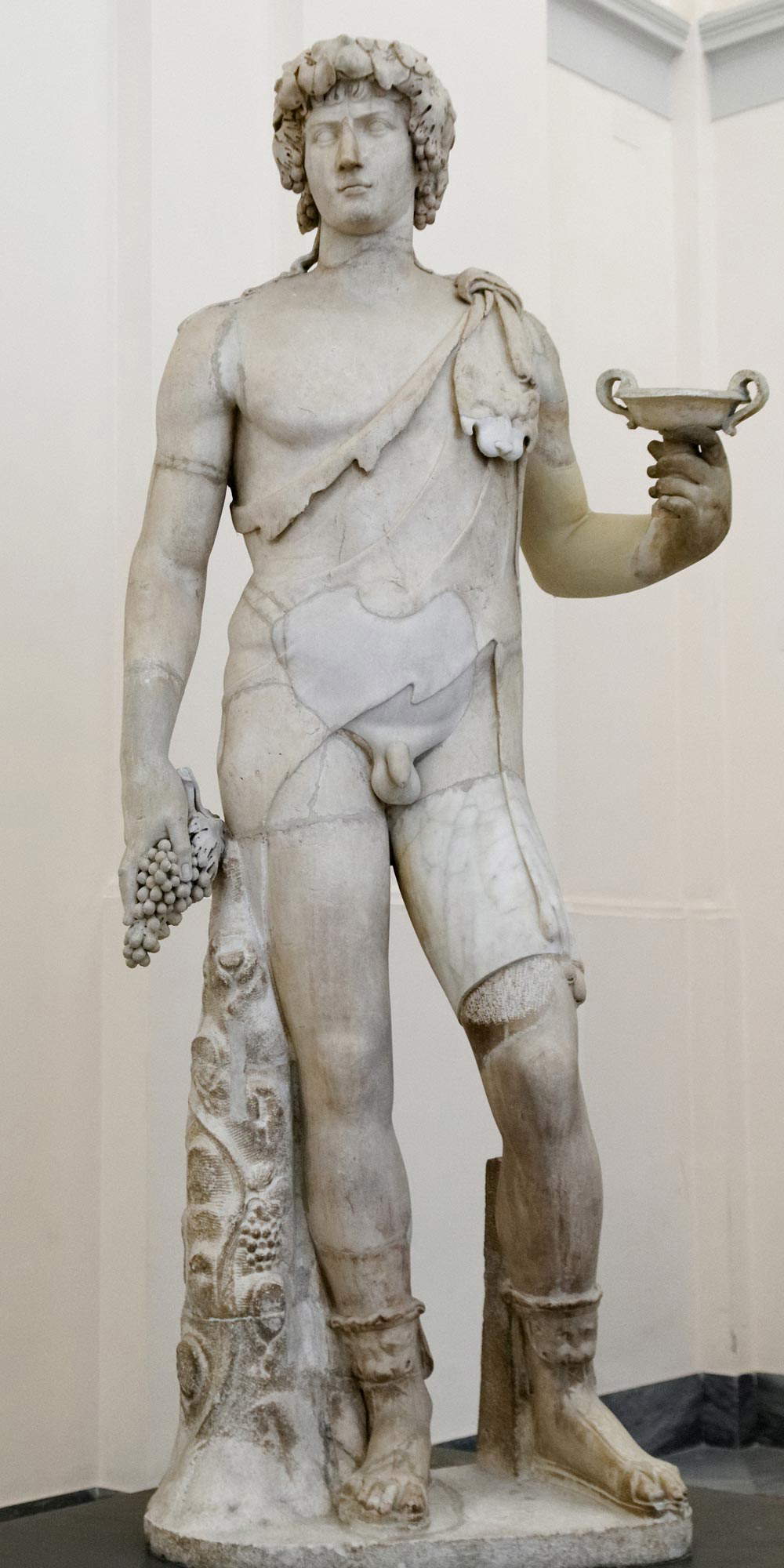

Classical references lead to the topic of iconographic sources from which Caravaggio may have drawn for his Bacchus. Several scholars, starting with Walter Friedländer, have pointed out, as partly anticipated above, the dependence of the sensuality of the Uffizi painting on depictions of Antinous-Bacco of the Hadrianic age: one example is the Antinous in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, formerly located at the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, where Hadrian’s young lover is depicted in the guise of the god of intoxication. It is not certain that Caravaggio was directly familiar with the work now in Naples, but he certainly could have seen something similar in the rich collections of antiquities in Rome at the time, on all those of Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani, a great collector of ancient and modern art. Friedländer, again, then juxtaposed Caravaggio’s painting with a Bacchus preserved at the Galleria Estense, a work of Ferrara’s early 16th-century ambit that has also been attributed to Dosso Dossi: it is an allegorical figure that was part of a group of panels that decorated the bedroom of Duke Alfonso I d’Este in Ferrara. Caravaggio almost certainly had no direct knowledge of this work (the events of which, curiously enough, are intertwined with those of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, to whom it was sent by mistake in 1607, a year in which Michelangelo Merisi had already left Rome anyway, never to return), but according to the German scholar it is nonetheless an example of an image with which Caravaggio might have been familiar: images of ancient divinities that became sophisticated allegories. On the other hand, a juxtaposition suggested by Alfred Moir in 1982 seems particularly timely, when he pointed out the close resemblance of the pose of Caravaggio’s Bacchus to the one painted by Federico Zuccari around 1584-1585 for the frescoed room of his residence in Florence (Palazzo Zuccari on Via Giusti).

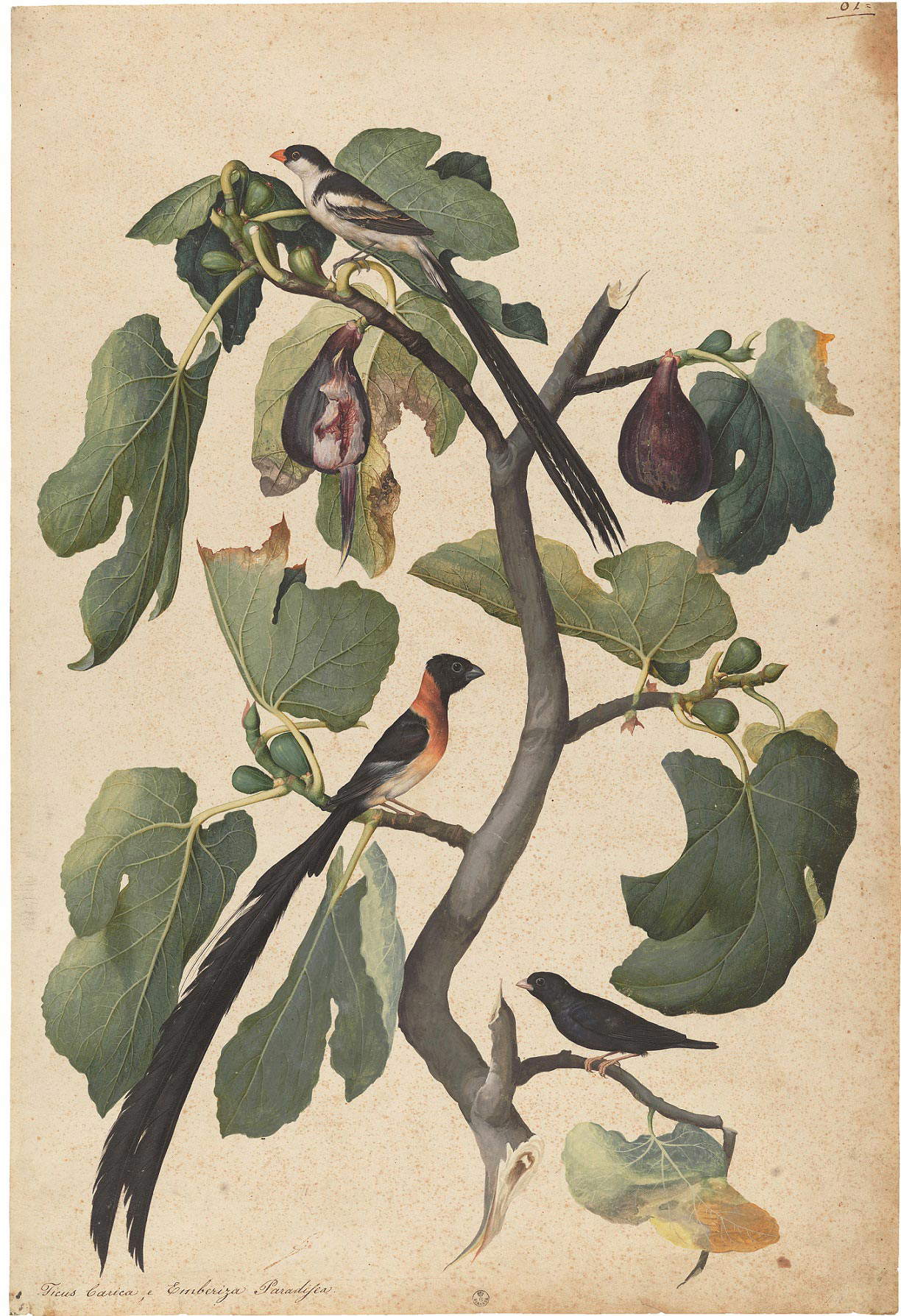

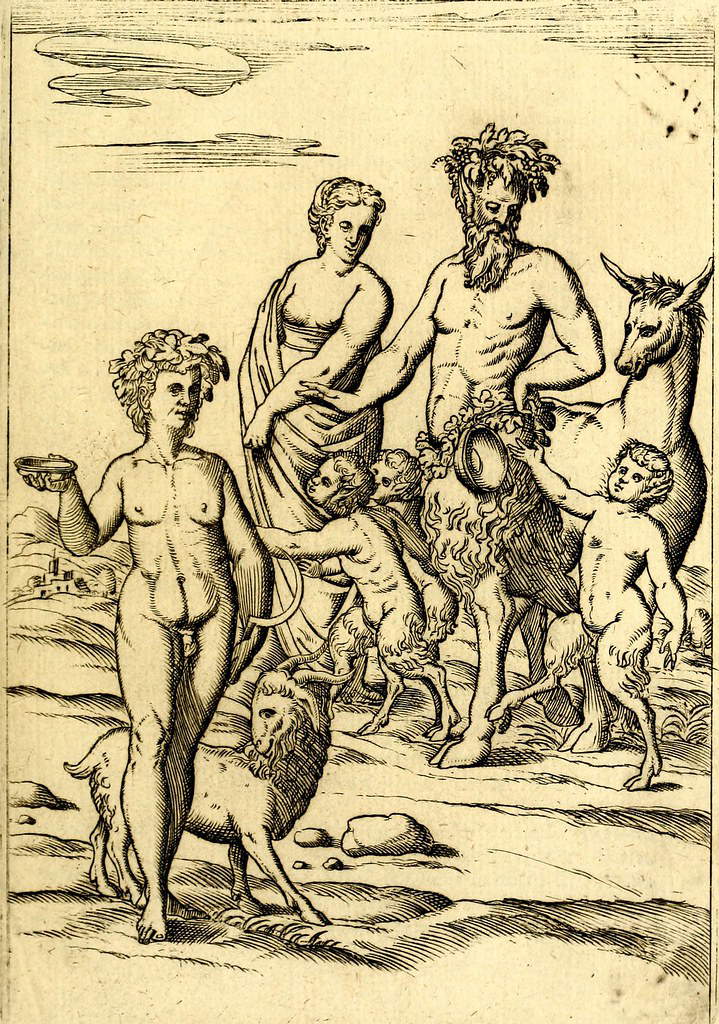

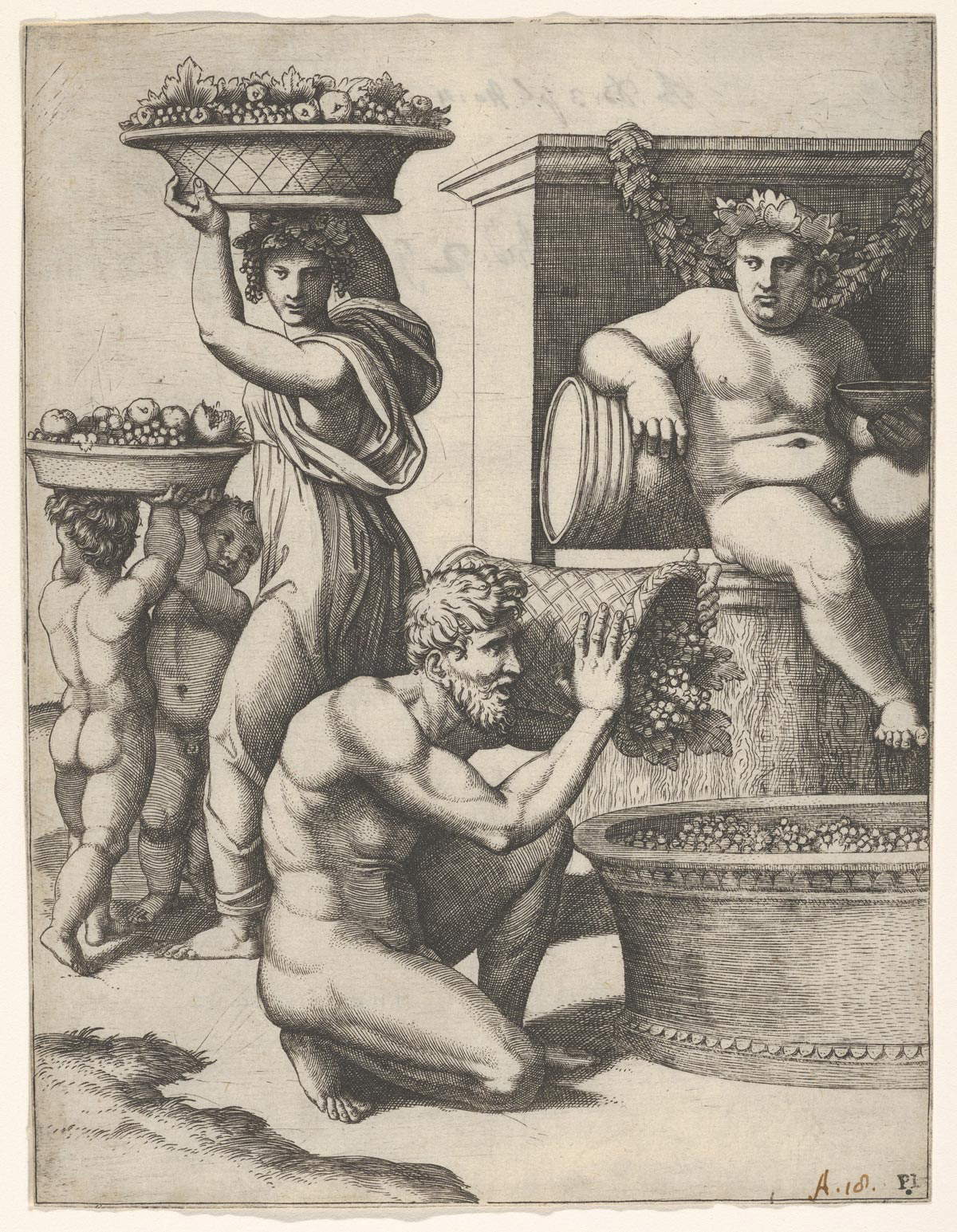

Mina Gregori, on the other hand, pointed out the connection between the Bacchus and the works of the great Lombard painters of the 16th century (Moretto, Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo, and Giovanni Battista Moroni), whom Caravaggio, on the other hand, knew very well. This is mainly a stylistic dependence: the use of contrasting colors, the dark outline to enhance the volumetries (this can be seen in the hand near the chest and in the pitcher) derive from the lesson of the Brescians. In particular, Mina Gregori again pointed out, the reference is to Moretto as far as the foreshortened representation of the figure and the emphasis on the surfaces are concerned, while the flare of light would derive from Moroni (one could take the Tagliapanni in the National Gallery in London as an example). “The Bacchus,” the scholar wrote, “demonstrates perhaps more than any other work by Merisi his descent from 16th-century Brescian painting. The plastic and illusory result obtained by contrasts of color and aided by a darker margin partly obtained by leaving the preparation in reserve, which helps to give relief and render the succession of objects in the depth of space [...] goes back to a practice used in the sixteenth century by the Brescians (Moretto, Moroni) and continued until Ceruti.” Already Longhi, for example, had likened the still life piece to that painted by Moretto in the Madonna Enthroned between Saints Andrew, Eusebia, Domno and Domneone preserved on the first right altar of the church of Sant’Andrea in Bergamo. And precisely because of the precision of the depiction of fruit, again Mina Gregori wanted to identify Jacopo Ligozzi ’s precise scientific tables as the most immediate precedent for Caravaggio’s fruit. Singular, on the other hand, is a hypothesis of Bernard Berenson, who, because of the vaguely oriental aspect of the features of the model posing for Bacchus, likened the image to that of the Indian deities of the sculpture of Greco-Buddhist art, the kind developed in Central Asia after the conquest of Alexander the Great. According to Giacomo Berra, however, it is not to be ruled out that Caravaggio consulted an iconographic manual such as Vincenzo Cartari’s Le imagini de i dei de gli antichi, where an engraving by Bolognino Zaltieri is published in which Bacchus is depicted nude, with his head crowned with Pampini, and caught holding a cup of wine. Another engraving that Caravaggio may have looked to, according to Berra, is Marcantonio Raimondi’s Vendemmia on a drawing by Giovanni Francesco Penni: Michelangelo Merisi, in particular, would have “ennobled” the image of the fat and tired god that appears in this and other earlier depictions (another example is the Bacchus painted by Romanino in the loggia of the Buonconsiglio Castle in Trent), “updating” them on the ancient Antinoo-Bacco images (which had fascinated so many artists in the sixteenth century, starting with Raphael) and thus lending a classical patina to his wine god.

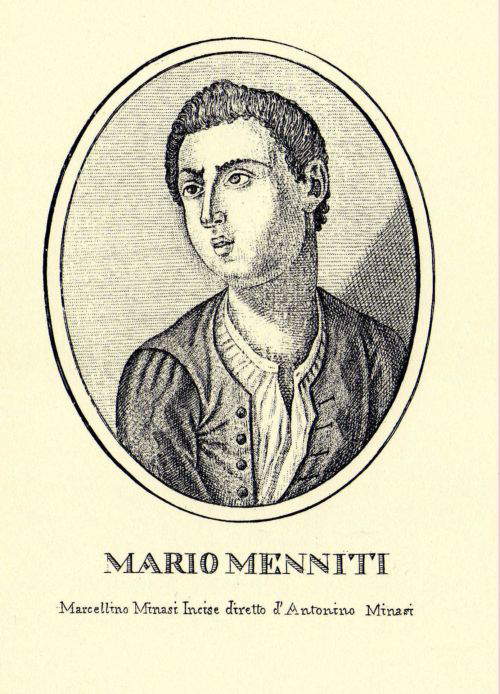

The model that posed for the Uffizi’s Bacchus can be found in other Caravaggio paintings: for example, the Lute Player in the two examples in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Metropolitan in New York, or the Good Fortune in the Louvre’s version, and again the Ragazzo morso da un ramarro (Boy Bitten by a Lizard ) in the Longhi Foundation, all works made in the same turn of years, between 1596 and 1598. Initially, Jacob Hess in 1954 proposed identifying the model as the painter Lionello Spada, while in 1971 Christoph Frommel solved the problem definitively by identifying the young man who posed for the Bacchus and the other paintings as the Sicilian painter Mario Minniti (Syracuse, 1577 - 1640), then in his early twenties and active in Rome, where he had met Caravaggio and become his friend, collaborator, model and perhaps even lover. The two also lived together, as we know from a 1603 court deposition by Caravaggio. Frommel found the similarity between Caravaggio’s model and the portrait of Mario Minniti executed by Marcellino Minasi and published in Memorie de’ pittori messinesi e degli esteri che in Messina fiorirono dal secolo XII sino al secolo XIX, by Giuseppe Grosso Cacopardo in 1821.

It may be the various interpretations or the different hypotheses about the identification of the model Caravaggio used for his Bacchus, or even the extraordinary and meticulous naturalistic pieces that encircle the head of the young man portrayed and adorn the surface in the foreground: Caravaggio’s Bacchus in the Uffizi fascinates anyone who lingers in front of it, probably also because it is different from the usual representations of the god of wine. He is a living, human figure, far from divine, turning his gaze toward the viewer. The very gaze and gesture he makes as he raises his glass seems to invite the latter to participate in the scene. Like the observer in fact, Bacchus, far from Olympus, is real and shares with him the pleasures of earthly life, but also the transience of life and imperfection. This is probably why Caravaggio’s characters still fascinate so much today. And the Bacchus in the Uffizi is a significant example of this.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.