On the night of Oct. 17-18, 1969, Caravaggio ’s Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis (Milan, 1571 Porto Ercole, 1610), one of the Lombard painter’s most celebrated masterpieces, was stolen from its original location, the loratoryof San Lorenzo in Palermo, and has never been found since. There have been various rumors about the sensational theft, attributed to the Mafia(including the most horrific ones that want the painting destroyed), but the only certainty is that, unfortunately, at the moment we have no sure leads to follow, and the hopes of finding the work are almost nil. Despite the sad circumstances, studies around the painting have certainly not ceased: far from it.

|

| Caravaggio, Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis (1600; oil on canvas, 268 x 197 cm; Palermo, formerly in the Oratory of San Lorenzo, stolen in 1969) |

The painting has long been considered to be a work made by the artist during his Sicilian sojourn: Caravaggio stayed in Sicily between 1608 and 1609, and until recently it was believed, with a good margin of safety, that the painter had been waiting to make the Nativity precisely at that juncture. The suspicion that that was the painting’s desecution period was fueled by the accounts of his early biographers. Although no documents have survived attesting to a passage of Caravaggio from Palermo, Giovanni Baglione first and Giovan Pietro Bellori later speak of a transit of the painter from the Sicilian capital. If Baglione, in his Lives de pittori, scultori et architetti of 1642, wrote that Caravaggio arrived on the island of Sicily and worked on some things in Palermo, Bellori, thirty years later, in his Lives of 1672 echoed him by attesting that as he passed through Sicily, from Messina he moved to Palermo, where for the Oratory of the Compagnia di San Lorenzo he did another Nativity. Since the stay in Messina lasted until early 1609 and since in the summer of the same year the Lombard artist returned to Naples, according to the statements of Baglione and Bellori it was thought that the Nativity was executed in 1609.

Yet the style of the painting deviates from that of the works created during the Sicilian sojourn. So much so that, since the 1920s, scholars began to question whether the Nativity had been painted long before the date to which it was conventionally ascribed. The first to instill doubts was Enrico Mauceri, who in 1924 proposed dating the Nativity to Caravaggio’s Roman period, for purely stylistic reasons. In 1951 Edoardo Arslan returned to the issue, who identified a certain closeness to the chromaticisms of Romanino (Girolamo Romani, Brescia, 1484/1487 after 1562) and to Morettesque instances (the cartouche bearing the angelic linnet Gloria in excelsis Deo held by the angel arriving in flight above the protagonists): similarities sufficient to lead one to think that the work departed from the works of the extreme stages of Caravaggio’s career and to believe that it might have been brought to Sicily by the Prior of the Hospital of the Consolation, the place where Caravaggio, in 1600, had been hospitalized. Another insight came in 1982 from Alfred Moir, who agreed that the style of the work was incompatible with that of the Sicilian paintings, and noted the similarity between the dimensions of the Nativity and those mentioned in the contract that the painter entered into in 1600 in Rome with a certain Fabio de Sartis (a contract in which, however, there was no mention of what the subject was). The latter was none other than the Sienese dorigin merchant Fabio Nuti (Fabio de Sartis was simply a transcription error from the document), with whom Caravaggio, on April 5, 1600, in Rome, had entered into the above-mentioned contract, discovered in 1971, which provided for the artist’s commitment to create a work cum figuris (with figures: however, they were not specified in the document), 12 palms high by 7 or 8 wide. Moir’s intuition proved decisive, and would be taken up some thirty years later by Maurizio Calvesi, who, finding pertinent a placement of the painting in the 1600s, speculated that, perhaps, it was precisely the Nativity that the Sienese merchant had requested from Caravaggio.

Scholars thus began to wonder which was the painting cum figuris mentioned in the contract: a possible confirmation regarding the trail leading to the Nativity (which, in the entire Caravaggio corpus, is the painting whose dimensions come closest to those reported in the contract) came, however, only thanks to the discovery of a document attesting to the relationship between Fabio Nuti and Palermo. Evidence of such frequentation was found in 2012 by Giovanni Mendola: it is a letter of exchange, dating from March 1601, attesting to a financial transaction between Fabio Nuti (whose business dealings with southern Italy were already well known) and Cesare de Avosta, one of the confreres of the Compagnia di San Francesco, which had its headquarters at the Oratory of San Lorenzo and whose members included several merchants. Admittedly, this is not a document concerning the work, but it is nonetheless an important piece of evidence, which showed that there were connections between the Sienese merchant and the Palermitan loratorio, which is why it is not far-fetched to speculate that the Nativity was commissioned by Fabio Nuti for the loratorio of San Lorenzo, given also that the work had to be ready by the beginning of the summer (in time, therefore, to be delivered to the loratorio by the feast of San Lorenzo, August 10). Definitive and incontrovertible evidence is lacking, but the picture is complete enough to have convinced several scholars (from Claudio Strinati to Alessandro Zuccari, from Francesca Curti to Keith Christiansen, from Clovis Whitfield to Vittorio Sgarbi).

The chronologically most recent opinion is that of Nicola Spinosa, and we present it in this article with an unpublished video, which can be reached by clicking here: in the recording, made during a meeting held on May 7 as part of the Sky Arte Festival (Operation Caravaggio. Technology at the Service of Lost Art, with Peter Glidewell, Nicola Spinosa and Jordi García Pons), we can hear the Caravaggio scholar argue that contrary to what has always been believed, the painting was not made in Palermo [...]. In truth, it is now established that Caravaggio painted this Nativity never thinking about it going to the Oratory of San Lorenzo: he painted this work in Rome.

Early scholars, after all, had well seen the stylistic similarities between the Nativity and Caravaggio’s Roman paintings , and many noted how certain motifs recurred. One can therefore, at this point, look at the painting (through reproductions, of course) more closely. The group of the three main characters, namely Baby Jesus, the Madonna and St. Joseph, appears slightly shifted to the right. The fulcrum of the narrative, as one might expect, is the little Jesus, who, placed in the center of the composition, resting naked on a miserable straw mattress, no longer shines by his own light, as was the case with many of his counterparts who populated contemporary Nativities, but is more realistically affected by the light source on the left, which cuts his figure in two, illuminating his face and shoulders and leaving the rest of his body in semi-darkness. The same light radiates Mary’s face: she is a beautiful commoner with brown hair, thin dark eyebrows and a sharp face, caught in contemplation of her son. St. Joseph is depicted, with a very original iconographic choice, from behind, as if, by placing the saint in the position of the viewer of the painting, the painter had wanted to directly involve us who are looking: we see the nape of his neck covered by white hair and his body twisting to address the figure behind him, whose identification is still uncertain (for some it could be Friar Leo of Assisi, companion and confessor of St. Francis: on this opinion, however, Rodolfo Papa does not agree, who more simply identifies an anonymous shepherd in the figure). Saint Joseph, with his right hand, is making a nod, as if to invite the man to adore his son. St. Lawrence, on the left, and St. Francis, on the right, the first titular saint of the oratory for which the painting was intended, and the second eponymous saint of the company that, as anticipated, was based at the Palermo oratory, already appear to be engaged in this activity. The scene takes place inside a hut covered by a thatched roof and is balanced, on the left, by the angel who arrives holding the scroll rolled up on his left arm.

|

| Detail with the Child, Our Lady and St. Joseph. |

On closer inspection, there are many details that distance the Nativity from the works executed during the Sicilian sojourn (the Resurrection of Lazarus and the Adorationof the Shepherds now in the Regional Museum of Messina, and the Burial of Saint Lucy in the church of Santa Lucia in Syracuse). To begin with, all of Michelangelo Merisi ’s Sicilian works are sharply divided into two registers: the upper one is always a large empty space, which is completely absent from the Nativity. Moreover, the stolen painting presented, at least according to the photographic reproductions available to us, a less gloomy and somber coloring than that which characterizes the Sicilian works, all of which were painted, as Mauceri wrote, in quite agitated danimo conditions, and with perhaps not good colors found on site. Again, the Sicilian works appear as if framed from a distance, with the characters appearing distant, and not as close together as is the case with the Nativity. For these reasons, too, it has seemed to many to lack credibility to place a painting like the Nativity close to the other Sicilian works, compared to it so profoundly different. And differences also concern the support: scientific analyses carried out on the canvas show that it has the same technical characteristics as Michelangelo Merisi’s great Roman paintings, quite different from those of the Sicilian paintings executed on several canvases sewn together (the Palermo Nativity, on the other hand, was painted on a single canvas).

|

| Caravaggio, The Resurrection of Lazarus (1609; oil on canvas, 380 x 275 cm; Messina, Museo Regionale) |

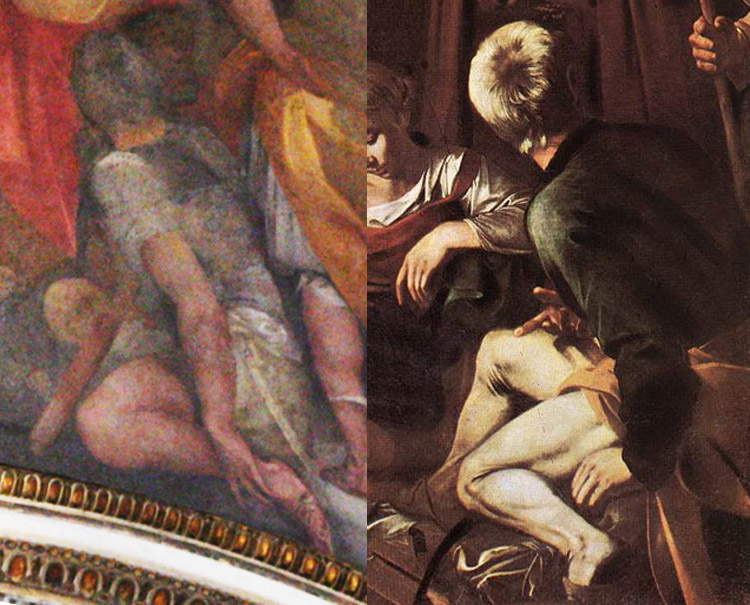

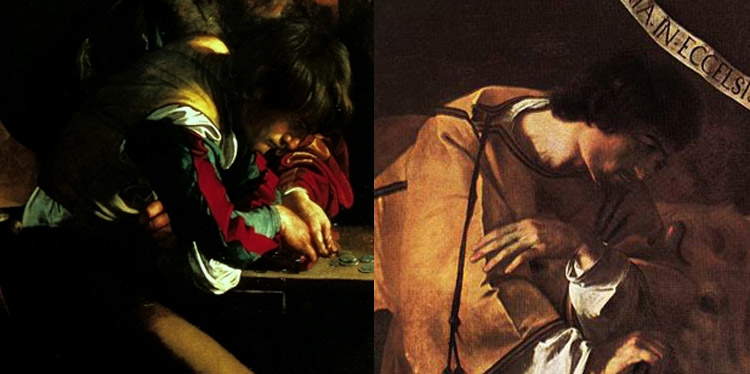

On the contrary, there are several reasons that bring the lost Palermo painting closer to the works made during the Roman sojourn, and in particular to those executed in the vicinity of the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, to which Caravaggio waited between 1599 and 1602. The examination could start precisely from the beautiful Virgin, whose somatic features resemble those of the Judith preserved in Rome, at Palazzo Barberini, and whose most recent research has proposed dating to 1602, meeting with wide critical favor. Impressive then is the resemblance, noted by Michele Cuppone, between the figure of St. Joseph and that of the soldier who appears in the Miracle of St. Matthew Resurrecting the Son of the King of Ethiopia, one of the frescoes that Cavalier dArpino (Giuseppe Cesari, Arpino, 1568 Rome, 1640) executed in the Contarelli Chapel before the work passed to the younger Milanese artist: the pose of the two figures is practically identical. Similarities then unite the profile of St. Lawrence with the man we see on the left in The Calling of St. Matthew, bent over the table, caught in the act of counting coins. Again, one could look at the Nativity ’s langelo and compare it with the St. Matthew and langelo painted for the Contarelli Chapel, where the langelo appears in a pose quite similar to that of his Palermo counterpart: a detail that, according to Alessandro Zuccari, proves that Merisi not only reused the same model, but also reproposed the pose he had already studied and certainly already designed. To these similarities must then be added the Lombard memories that, a few years after his move to Rome, must have been still fresh to some extent, judging from theangelo bearing a cartouche that, as mentioned above, reminded Arslan of the thick, heavy, crumpled cartouches that Moretto ’s putti (Alessandro Bonvicino, Brescia, 1498 ca. 1554) held in many of his works (examples are the Adorationof the Shepherds with Saints Nazario and Celso in the church of Santi Nazario e Celso in Brescia, or the Adorationof the Shepherds executed for the church of Santa Maria della Ghiara in Verona and now preserved in Berlin). Could it be that Caravaggio, in Palermo, during a particularly hectic phase of his existence, kept Roman suggestions so alive?

|

| Comparison between the 1602 Judith and the Palermo Madonna of the Nativity |

|

| Comparison between the angel of St. Matthew and the angel of the Palermo Nativity |

|

| Comparison between Cavalier d’Arpino’s soldier and Caravaggio’s Saint Joseph |

|

| Comparison between the man in the Vocation of Saint Matthew and the Saint Lawrence of the Nativity |

|

| The angel of the Palermo Nativity |

|

| Moretto, Adoration of the Shepherds with Saints Nazario and Celso, detail of the angels (1540; oil on canvas, 380 x 320 cm; Brescia, Collegiate Church of Saints Nazaro and Celso) |

The coloring is as clear as that of the Roman years, the light as grazing as that of San Luigi dei Francesi, of the details it is amply said: should we want to go back to assuming a Sicilian dating, it would be a unique case. The result, however, is an enthralling nocturne that allows us to witness an intimate scene, capable of moving more than one observer to emotion, thanks to the touching tone with which Michelangelo Merisi treats his pictorial discoveries, as Roberto Longhi had written, from the St. Joseph in his electric green jacket and in the great reluctance of the lustrous dogia, through the shadowy half-tones of the two crib animals and the Brescian l’angelo, but spiking from above like a lily excavated from its own weight, to the miserable child, abandoned on the ground like a thrown tellin shell.

Today we can no longer enjoy the original, and in its absence, on December 12, 2015, a reproduction made by Factum Arte, a company specializing in the creation of high-fidelity artistic reproductions, was placed on the altar of the San Lorenzo oratory that housed Caravaggio’s painting. A reproduction conducted on the basis of only one of the two known color photographic images of Caravaggio’s work: a photo taken by Enzo Brai in 1967, used by Adam Lowe, founder of Factum Arte, and his team, and an additional image from 1964, preserved at theScala Archives. The less recent image was not taken into account by the technicians, despite the differences in rendering from the 1967 photograph: a lack that should make us reflect on the issue of reproducibility of works of art, a topic often neglected compared to others, certainly more urgent and more pressing, but no less important. And which becomes vital where, as in the case of the Palermo Nativity, the originals have been lost and it is necessary to rely exclusively on reproductions. The work of reconstructing the painting, while certainly unable to make up for the lack of the original, was nonetheless of considerable importance so that Palermo could once again enjoy at least the spirit that animated Caravaggio’s work.

|

| The altar in the Oratory of San Lorenzo before 2015, with a simple reproduction of the Brai photograph. Copyright Factum Arte |

|

| The altar today with a Factum Arte reproduction. Copyright Factum Arte |

Reference bibliography.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.