A sumptuous room for festivities, open to the lush and orderly garden, decorated with stucco and frescoes, and endowed with a majolica tiled floor, as well as a precious set of sculptures: such was the guise that, in 1750, the future doge of Genoa, Marcellino Durazzo, had envisioned for the Galleria delle Stagioni (or “Gallery of the Four Seasons”), the large hall destined to expand the structure of Villa Faraggiana, the splendid family residence in Albissola Marina. Although, since then, the room has undergone some modifications (the frescoes, for example, have undergone extensive makeovers), the fortunate visitor who finds himself walking through the Gallery today will walk into a room not so different from the one that welcomed the Durazzo family and their guests during sumptuous receptions. Particularly attracting our attention are the sculptures by Filippo Parodi (Genoa, 1630 - 1702), the greatest Baroque sculptor in Liguria, whose five works we observe: the allegories of the Four Seasons and the much-admired mirror with the Myth of Narcissus.

|

| Villa Faraggiana, Albissola Marina. The Gallery of the Seasons. Courtesy Albezzano srl |

We do not know what the original destination of the sculpture cycle was, nor who the patron was. Nevertheless, given the relations Parodi had forged with the Durazzo family, and since Carlo Giuseppe Ratti, in his 1769 Lives of Genoese Artists, already stated that the mirror was then present in Albissola, it is highly likely that the five works were made for a member of the noble dynasty, although the debate aimed at establishing who, exactly, ordered the statues is still ongoing: perhaps Giovanni Antonio Durazzo, who married Maddalena Spinola in 1667, thus in a year compatible with the dating of the works, assigned to the seventh decade of the seventeenth century, or Carlo Emanuele Durazzo, who in the same year was putting in place some modernization works in the large palace on Via Balbi in Genoa (now the Royal Palace). What is certain is that since that 1769, the year of the first attestation, Filippo Parodi’s works must have aroused high praise and universal awe. This is especially true of the wall table with the Myth of Narcissus. This is how Ratti speaks of it: the aforementioned Most Excellent Durazzo has in Albizzuola, within his villa palace, a beautiful mirror worked in the shape of a fountain, where Narcissus is wandering. A thing, which for its invention and naturalness, deserves the high esteem in which it is held. An esteem that has persisted to the present day: a specialist such as Alvar González-Palacios, in his 1996 publication on furniture in Liguria, called the mirror “the most beautiful Genoese piece of furniture in existence, one of the masterpieces of great European decoration.”

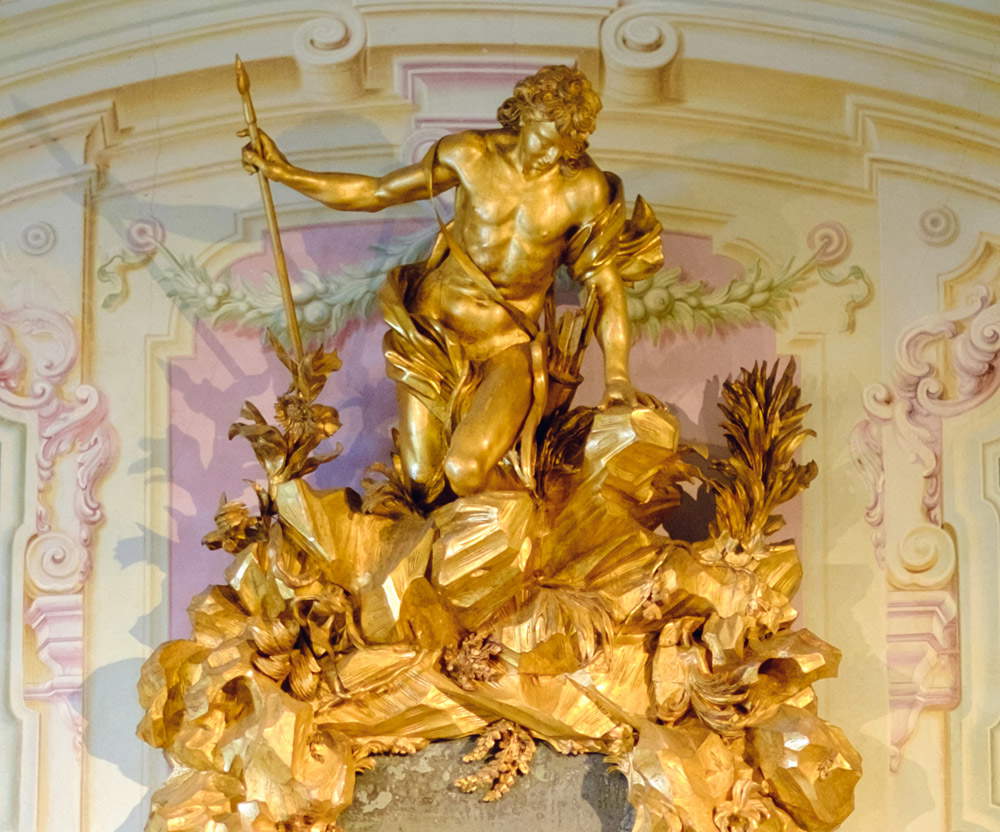

So what is the reason for so much praise for this work? Certainly, being in front of, in person, such a piece of furniture, made entirely of gilded wood, is an experience capable of dispelling all doubts. However, in order to suggest an idea by the mere means of the word imprinted on the paper, we can describe Filippo Parodi’s mirror as a high and impassable cliff at the base of which a spring of water gushes out: at the bottom, we notice two dogs drinking (one, in truth, is only approaching, the other is already standing upright on its hind legs to approach the water) and, at the top, the imposing yet delicate figure of Narcissus who, in a game of cross-references typical of Filippo Parodi’s production (and of seventeenth-century mirrors in general), gazes into the fountain while leaning on the spear with which he had gone hunting. All around we see maidenhair plants, shrubs, roots, and even some crabs hidden among the rocks. The myth, narrated by Ovid, tells us of this beautiful young man who stopped, during a hunting trip, to contemplate his own image reflected in a pool of water to which he had approached to drink, and who ended up falling in love with its appearance, so much so that he died worn out from the impossibility of his love.

|

| Filippo Parodi, Mirror with the Myth of Narcissus (seventh decade of the 17th century; carved and gilded wood, 450 x 170 x 70 cm; Albissola Marina, Villa Faraggiana). Courtesy Albezzano srl |

|

| Detail figure of Narcissus. Courtesy Albezzano srl |

|

| Detail of the right dog. Courtesy Albezzano srl |

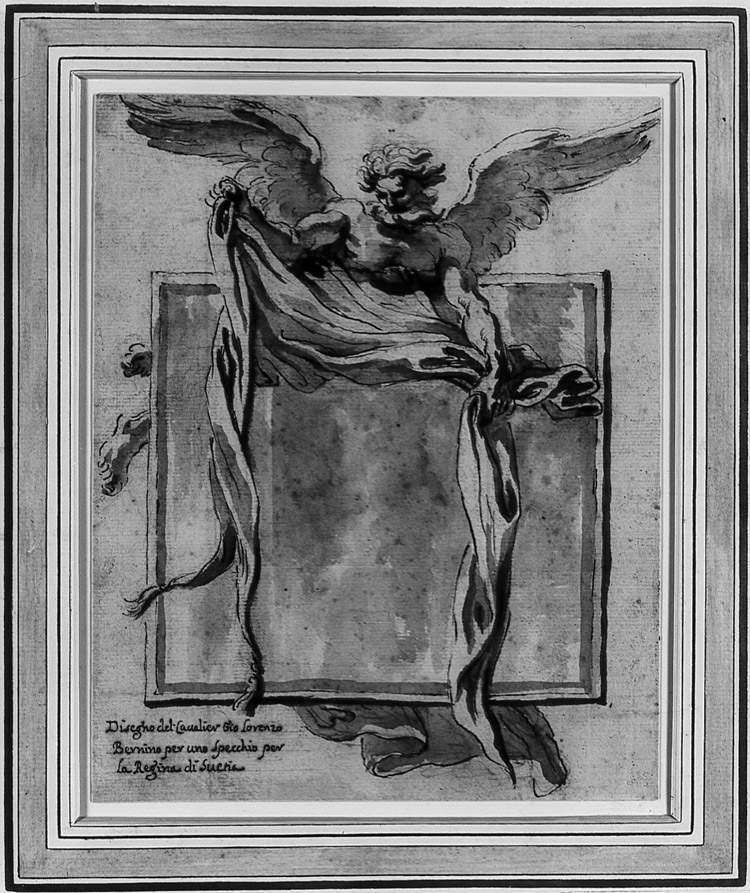

Filippo Parodi’s refined conceptual invention aims at several purposes: a first and perhaps most immediate objective is the negation of the physical place that hosts the work, to open a window on the “vital matter of nature” and to make the mirror a “natural element of an illusory space antithetical to the concept of architectural spatiality” (so Lauro Magnani). This deceptive component, which distinguishes Parodi’s complex figuration, is inherent in Baroque art, and the Genoese sculptor certainly had the opportunity to refine his skills in this regard with a stay in Rome, during which he came into contact with the most up-to-date solutions of Gian Lorenzo Bernini: (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) just think of the great celebratory machines and spectacular stage sets that were set up in 17th-century Rome, and which have also been discussed on these pages. Again, Parodi was probably able to benefit from the mediation of the imagination of an imaginative stage designer like the Tyrolean Johann Paul Schor (Innsbruck, 1615 - Rome, 1674), skilled in wood carving: it is perhaps also thanks to the proximity with the Austrian artist that Filippo Parodi matured his expertise in the art of carving. Parodi was probably able to study closely some of Schor’s daring inventions (such as the ceremonial bed for Maria Mancini, or the so-called “Small Table” at the Getty Museum whose design is attributed to him: in fact, the “Small Table” was probably part of a larger scenographic complex, and it is interesting because it is a phytomorphic object whose idea could constitute an interesting precedent for Parodi’s mirror), but also those of Bernini, such as the mirror for Cristina of Sweden. A scholar like Paola Rotondi Briasco, however, noted a trait that separated Parodi from Bernini: while both starting from a “strong naturalistic feeling,” Bernini did not lose sensual contact with reality, while Parodi sublimated it (the shapes of the rocks and especially the gilding are the favorite means of achieving this sort of abstraction) to bring the observer into a dimension far from the concrete and tangible or, in Rotondi Briasco’s words, to arrive at “a joyful pre-arcadic spirit” and an “idyllic and pastoral sensibility” transfigured into “a fabulously woodland setting.”

|

| Anonymous carver based on a drawing by Johann Paul Schor, Small Table (ca. 1670; carved and gilded wood, 170 x 224 x 84 cm; Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum) |

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Drawing for the Mirror of Christina of Sweden (c. 1662; pen and brown watercolor on paper, 23 x 18.8 cm; Windsor, The Royal Collection) |

Again, in keeping with a typically Baroque ambiguity, the viewer becomes the first-person protagonist of the work, transforming himself into a true alter ego of Narcissus: just as the mythical hunter is mirrored in the water, so the viewer sees his own image in the mirror that Parodi places between the rocks. The subtlety of such speculative machination has been noted by many of those who have studied the work: Filippo Parodi succeeds in transporting myth into reality in order to induce the viewer to reflect on the dangers faced by those who, like Narcissus, linger too long in vacuous vanity. It is, in other words, a moralizing allegory typical of the century, with the peculiarity that here the double warning about the transience of the human being and the risks that an excess of vainglory entails, is transformed into a sophisticated memento mori (vanity, after all, was fatal to Narcissus) concealed in the guise ofingenious artifice.

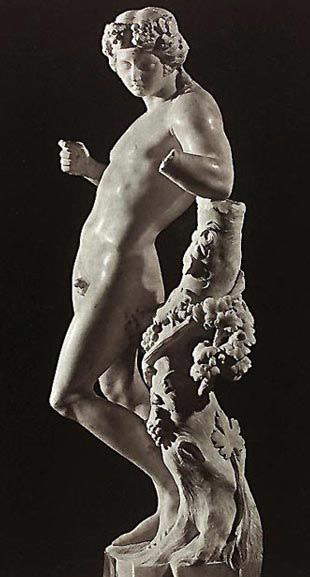

The cycle at Villa Faraggiana in Albissola Marina is enriched by the allegories of the Four Seasons, which were meant to play the role of points of light holding up candlesticks, and which demonstrate how the unity of sculpture and decor was a precise choice that guided the Gallery’s layout. The personifications of the seasons, arranged on the two long sides of the Gallery, are recognizable through their characteristic attributes: Spring andSummer are two young women distinguished, respectively, by a myrtle wreath and a bizarre garland of ears of corn,Autumn is a man surrounded by bunches of grapes, and finallyWinter is an old man striding through a barren landscape, covered by a broad cloak, and caught in the act of approaching a brazier to warm himself. Critics are divided on the actual authorship of the four sculptures: for some, they could be the work of a workshop, since they do not come close to the results offered by the mirror with the Myth of Narcissus, while for others, who have highlighted their refinement, taste and formal elegance, they would always be products of the hand of Filippo Parodi.

|

| Filippo Parodi, The Seasons in the Gallery (Seventh decade of the 17th century; Spring: 178 x 80 cm, Summer: 192 x 85 cm, Autumn: 163 x 86 cm, Winter: 170 x 50 cm; Albissola Marina, Villa Faraggiana). Courtesy Albezzano srl |

|

| Detail of Spring. Courtesy Albezzano srl |

|

| François Duquesnoy, Bacchus (1629; height 60 cm; Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj) |

Although Villa Faraggiana is located some distance from Genoa, its Gallery of the Four Seasons houses one of the most complex, spectacular and best-preserved examples of Genoese Baroque sculpture of which, as already remarked, Filippo Parodi was probably the highest representative. And the preciousness of such an apparatus is all the greater if we think that the sculptures are part of an excellently preserved context, still very similar to how the last inhabitants must have lived it, and which continues to be kept alive, for all to see, by private individuals who take care of Villa Faraggiana with scrupulous care and great attention. Exactly as the ancient owners did, whose great passion for art is preserved by the present ones. The same one that, in 1750, led the Durazzo family to decorate the Gallery of the Four Seasons with a cycle of statues that had profoundly renewed seventeenth-century Ligurian sculpture.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.