At the beginning of the 14th century, the church of Sant’Andrea in Pistoia was provided with new and important liturgical furnishings. By 1301, in fact, the sculptor Giovanni Pisano created a pulpit for this space that marked important novelties within the panorama of Italian sculpture. There were already three pulpits of considerable importance in Pistoia: two had been made by Guido da Como and one by Fra Guglielmo. Probably the commission of this prestigious work was made possible by the special role of this church: it was in fact the town parish church, thus possessing the right to baptize, and its parish priest, the plebanus, was considered second in importance after the bishop in the local ecclesiastical hierarchy. The church of St. Andrew was a central place for the entire Pistoiese community, both from a sacred and civic point of view: in fact, it was a place where ceremonies not only of a religious nature took place. The commissioner of this work was the plebano Arnoldo, who, thanks to funding from Andrea Vitelli and Tino Vitale, was able to entrust the task to one of the most prestigious sculptors of the time. This information comes not from a documentary record, which does not currently exist, but from the Latin inscription in Leonine verse found at the base of the hexagonal structure of Giovanni Pisano’s pulpit.

Its present location inside the church, between the fourth and fifth columns of the left aisle, does not correspond to the original one. It was in fact located near the penultimate column of the right aisle, opposite the chancel. The move probably took place around 1619 to comply with the new directions of the Council of Trent regarding liturgical guidelines. Following disassembly and relocation, the two lecterns were removed: that of the Gospel, depicting the Eagle of St. John, is kept at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and that of the Epistle, which bears carved one of the earliest depictions of the iconographic theme of the Pieta of Angels, at the State Museums in Berlin.

In this work, which is considered one of the masterpieces of Giovanni Pisano’s maturity, the sculptor takes up and develops the models made by his father, Nicola Pisano, for the pulpits for Siena Cathedral and Pisa Baptistery. Giovanni, who grew up in his father’s workshop, is counted among Nicola’s collaborators in the creation of the work for the Sienese community: he thus had the opportunity to deal firsthand with this type of artifact. In Pistoia, Giovanni proposed a hexagonal structure (as in Pisa), resting on as many columns, plus a central one, made of porphyry. As in the Sienese work, however, the mirror reliefs are separated by large sculpted figures. He converged in his Pistoiese design choices belonging to his father’s two previous signature pulpits. The decision to use three-lobed ogival arches, which give this structure a definite vertical thrust, contributes to a more Gothic feel.

Even at a first glance, it is possible to notice one of the great innovations proposed in this pulpit: John, in fact, succeeds in bringing out the plastic element in an extraordinary way with respect to the architectural one. The forms that the sculptor proposes are soft, as if they belonged to a continuous flow, and plastically enhanced by important chiaroscuro contrasts: his sculpture seems to take life from the architectural structure. It should be considered that originally this aspect was even more evident due to the glazing of the base surface, the use of color in the reverse of the draperies, and a gilding of the edge of the robes. John carries forward his conception of sculpture here, arguing that it is predominant over architecture. He had already proposed this thought of his in the facade of Siena Cathedral, in which architecture is seen as a stage for his celebrated cycle of sculptures, among which the powerful figure of the Mary of Moses may be mentioned. The sculptures that John offers are animated by the wide range of human emotions, which he is able to impart to marble through his great technical skill through the use of tools such as chisels, rasps, gradine, and files as needed.

The content of the pulpit, which is meant to represent the history and the path of the Christian Redemption, is conceived on three levels: from the lower one, where the allegorical plane is located, it passes to the middle one that represents the prophetic one until it arrives at the historical one, in a higher position. The lower register consists of large figures whose function is to hold up the columns. A total of four are involved: three of the perimeter, alternately, and the central one. Supporting the latter, one can recognize a winged lion, an eagle, and a griffin to represent Christ, his Ascension, and his final return. At the foot of two of the perimeter columns are two felines: one is a Lion baying a Horse, symbolizing Christ’s victory over the Antichrist, while the other is a Lioness suckling her cubs, alluding to the Redemption. Holding up the third column is one of the most expressively powerful figures in the entire work: it is the so-called Atlas, John’s original iconographic invention in a similar context. There are several interpretations that can be given to this figure: it is possible that it is an allusion to Adam, the first man on Earth, but it can also be thought to allude to a prefiguration of Christ. Just as Atlas carried the vault of heaven on his shoulders, Christ took upon himself the sins of men. The strength of this image lies entirely in its form: John makes an extreme figure in his suffering, hollowed out and emaciated, from whom it is impossible not to become emotionally involved. The Johannine Atlas has the appearance of a mature man, with a thick beard and few robes covering his body. His limbs are shot through with vibrant emotional tension, and the uncomfortable kneeling position accentuates the suffering of this character. Some of the details, such as the skin of the chest, are of extraordinary realism: combined with the great ability to bring out through the gaze his torment and fatigue, makes this character truly exceptional. It is a figure that can be viewed from different angles without losing its communicative power. It was originally placed under the Nativity relief so that it would be one of the first images visible upon entering the church. Following seventeenth-century dismantling, Atlas found its place under the Last Judgment, where it still stands today.

The intermediate floor, the one with prophetic significance, sees the presence of six Sibyls, to represent the pagan world, and some prophets, such as David and Solomon, recognizable by the crown they wear, for the Jewish one. Even in these individual figures we can appreciate John’s ability to impart well-defined emotions to the sculpted material. For example, we can read through the body and expression of one of the Sibyls her disturbance with respect to the Angel who, from behind, is suggesting prophetic revelations to her.

In the third level, the historical level, episodes from the history of Redemption are depicted in the five mirrors of the balustrade: the Nativity of Jesus, theAdoration of the Magi, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Crucifixion, and the Last Judgment. The five reliefs are separated by figurines, some of which are difficult to identify iconographically, but which nevertheless do not interrupt the rhythm of the composition. Several episodes can be identified in the first two reliefs. In the first panel, that of the Nativity, the moment of the actual nativity can be recognized in the central area: the Virgin is lying down and looking at the Child. On the left side is the episode of the Annunciation, while in the lower area is depicted the first bathing of the child, with two maidens preparing water. On either side of the scene can be recognized St. Joseph, absorbed in his thoughts, and the shepherds who, following the star, rush to adore the newborn Savior. It is a crowded composition of men and animals, but each manages to find its own space and emerge. Each character brings to the scene not only their physicality but also their emotions. With careful observation, traces of the glass paste that originally covered the background surface can be discerned in some areas of this relief.

Next, is the panel of theAdoration of the Magi with an orderly and balanced composition. In the center of the relief, the Magi are introduced by an Angel into the presence of the Child, who is in the arms of the Virgin. On either side of the central scene, two dreams are depicted: on the left that of the Magi, on the right that of St. Joseph. The three Magi share the same bed and blanket, as was customary during the Middle Ages. Each is characterized by a distinct reaction: there is astonishment, curiosity and disbelief, each manifested through precise gestures rendered with great naturalness. Even in the central scene, John gives the gestures freshness and spontaneity. For example, the king who is kneeling before the Child does not have the crown on his head but is tucked into his arm so that he can more easily kiss the infant’s foot. One of the other two Magi, waiting for his own time to pay homage to the Savior, has placed his own gift under his arm. John thus reasons about the verisimilitude of his iconographic proposals, finding new solutions to earlier models.

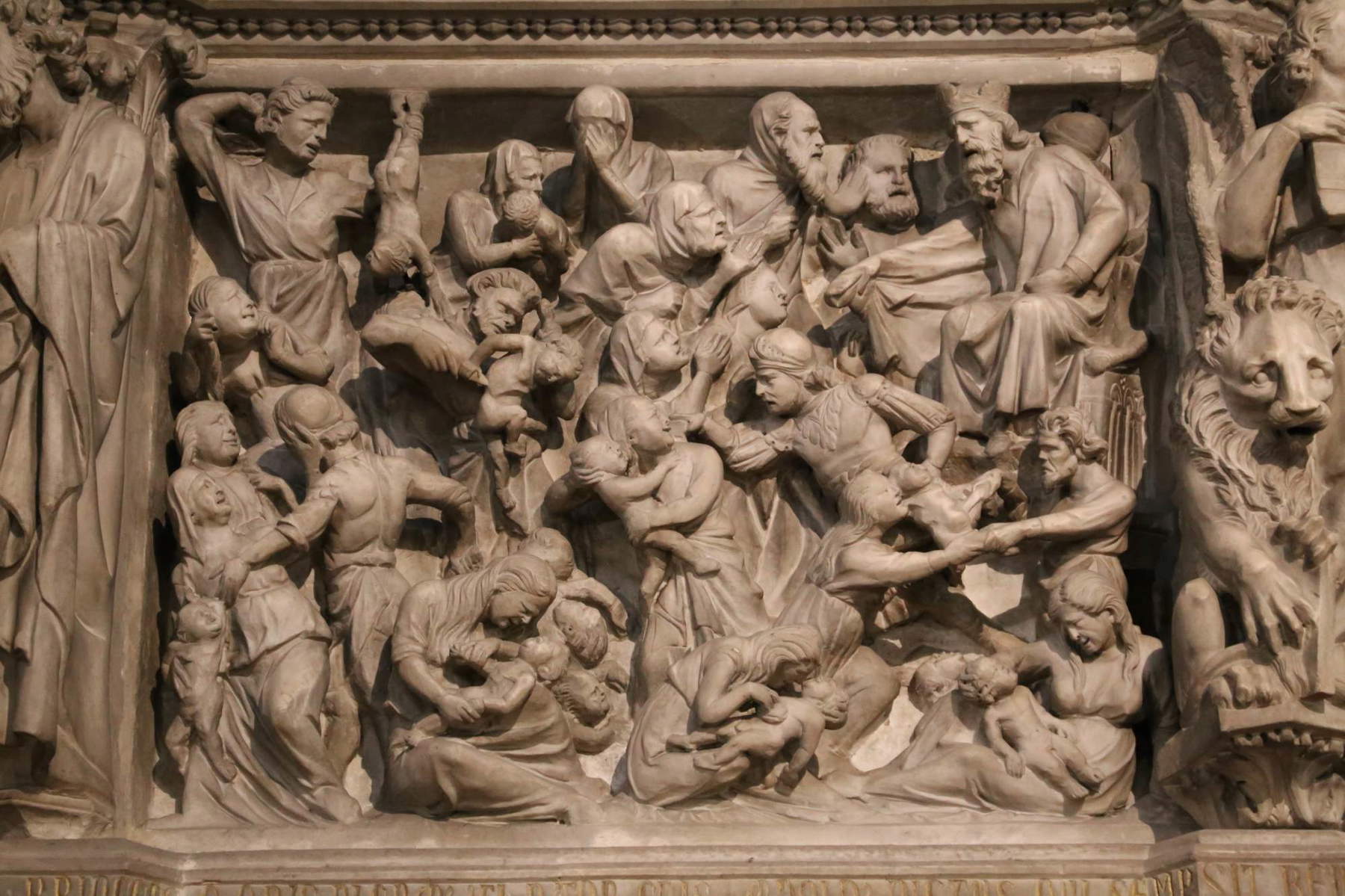

Great care is also found in the heads of the three horses of the Magi, made in foreshortening, thus demonstrating his spatial awareness. The episode depicted in the next scene provides the sculptor with an opportunity to unleash his skill in depicting emotions. It is in fact the Slaughter of the Innocents, an episode that naturally lends itself to being the scene of the drama experienced by mothers deprived of their male infants. The scene is a maelstrom of tension in which the grimaces of pain on the faces of the unfortunate mothers follow one another, while the bodies appear more indistinct, almost as if they were part of the same unit. Herod’s outstretched arm, imparting the order to kill the male infants, seems to create a shockwave in the composition, with the mothers and children desperately trying to get away and escape that gesture and tragic fate. This tile is one of the dramatic pinnacles of medieval sculpture, and John achieves extraordinary results in his depiction of human emotions and passions.

The Crucifixion and the Last Judgment are two very crowded scenes, in which the figures are organized according to a skillful conception of the planes of composition and emphasized through chiaroscuro play. Even in these two panels, although the iconography is traditional, the vehemence of the Johannine passions is the undoubtedly predominant element. Admirable is the image of Christ on the cross, with extremely tense limbs and a deeply hollowed abdomen, which stands in fruitful comparison with the coeval production of wooden or ivory crucifixes made by this sculptor.

The figures sculpted by Giovanni always appear to be in movement, not only physical but also emotional. He moves away from the classical and majestic canon of harmony proposed by his father to explore the territory of rendering human emotions and torments. Through meticulous attention to looks and gestures, which move from gentleness to despair, Giovanni reaches one of the heights of the expressive potential and human depth of his sculpture.

The author of this article: Francesca Interguglielmi

Storica dell'arte, laureata in Arte Medievale presso l'Università degli Studi di Siena. Attualmente si sta formando in didattica museale presso l'Università degli Studi Roma Tre.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.