It is curious to think that Guido Reni ’s Samson Victorious (Bologna, 1575 - 1642), one of the most famous works of the seventeenth century, now preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, was originally intended to decorate a fireplace: in fact, the canvas was commissioned to the great artist by a Bolognese nobleman, Count Francesco Maria Zambeccari, who wanted it as an over-fireplace for his residence, and this also explains the painting’s original and unusual mixtilinear form, with two volutes flanking a lobed centina, a structure that enhances the strength of thebiblical hero (“the Samson,” wrote art historian Gian Carlo Cavalli, “appears as a living statue within the premeditated niche”). The work was made between 1614 and 1616 and remained in the count’s house until 1664, when it was purchased, thanks to the interest of an important Bolognese artist of the time, Lorenzo Pasinelli, by the archbishop of Bologna, Girolamo Boncompagni, who in turn, in the year of his death, namely 1684, left the victorious Samson to the Senate of the city of Bologna. The works from Bologna’s public collections later flowed largely into the collections of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna in the Napoleonic era, and we can still admire the work today in the institute on Via Belle Arti, inside the room dedicated precisely to Guido Reni.

Carlo Cesare Malvasia already speaks of the painting in Felsina pittrice, the collection of lives of Bolognese painters published in 1678: Malvasia describes it as “Il superbo Sansone fatto per il camino della Sala del Sig. Co. Francesco Maria Zambeccari, now owned, among other distinguished pieces by the same Guido, by the Eminentiss. Sig. Card. Boncompagno vigilantissimo our Archbishop.” The work, by virtue of the strong interest that aroused, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the artists who were in the groove of seventeenth-century classicism, would have enjoyed some success in that period: among those who wrote about it, a passage by Percy Bysshe Shelley , who spent some time in Bologna during his trip to Italy, which began in 1818 and ended tragically in 1822, and who had the opportunity to visit the recently opened Pinacoteca Nazionale, deserves mention. “I saw much more of Guido,” reads one of his recollections of his Bologna sojourn published posthumously in Essays, “a Samson drinking water from the jaw of a donkey in the midst of the slaughtered Philistines. Why he should do this, only God who gave him this jaw knows, but certain is that the painting is very beautiful. The figure of Samson is in strong relief in the foreground, colored, as it were, in the hues of human life, and full of strength and elegance. Around him lie the Philistines in all attitudes of death. One prone with the slight convulsions of pain barely passing from his forehead, while on his lips and chin lies death as heavy as sleep. Another leaning on his arm, his motionless white hand hanging in front of him. In the distance more corpses. And still farther on, the blue sea and blue mountains and a quiet white sail.”

The subject depicted, the biblical hero Samson, had already been tackled other times in recent years: a few years earlier, Pieter Paul Rubens had executed a painting depicting Samson and Delilah (1609 work now at the National Gallery in London), a subject also chosen by the Dutchman Gerrit van Honthorst for one of his famous paintings of about 1615, not to forget then Annibale Carracci’s painting preserved at the Galleria Borghese in Rome and depicting Samson in Prison . Caravaggio also shortly before, in 1607, had depicted the hero in one of his paintings, the Seven Works of Mercy, kept at the Pio Monte della Misericordia church in Naples: Caravaggio’s Samson performs the same gesture as Guido Reni’s, namely drinking water from a donkey’s jaw, and it is necessary to point out that, in Caravaggio’s painting, the hero symbolizes one of the works of mercy required by Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel in order to be able to gain the kingdom of heaven, namely giving drink to the thirsty. The legend of Samson is told in the Old Testament, specifically in the book of Judges. The strength of the biblical hero has become proverbial, a strength that had been granted to him by God and that enabled him to accomplish great feats: one such feat is the one referred to in the painting. For Samson had clashed with the Philistines, who had captured him, bound him with ropes and taken him to the city of Lechi. But the hero, thanks to his prodigious strength transmitted to him by God, managed to break the ropes, then found a donkey’s jawbone and with this, used as a weapon, killed a thousand of his opponents. Following the victory, because Samson was thirsty, God caused a spring to gush forth from the ground by whose water the hero was able to quench his thirst. An error in an ancient translation of the book of Judges led to confusing the name of the place on which the clash took place, the “mount of the Jaw,” with the jawbone itself, leading to the misunderstanding of the water gushing directly from the jawbone: this is why we observe the hero drinking from the donkey bone.

Guido Reni’s Samson the Victorious depicts the hero at the moment when he has finished fighting his enemies and is drinking the water collected from the spring with the donkey’s jawbone. The chosen theme is suitable for depicting the figure of a leader with a sculptural physique, in a pose that highlights his muscles delineated with obvious anatomical skill, since Guido Reni decides to depict his hero nude, except for an orange veil that encircles his waist and covers his genitals and moves unnaturally, recalling the fluttering of Raphael’s Galatea in the Villa Farnesina. The pose is theatrical: Samson is shown with his body facing the viewer frontally, his head in a twist turns toward the donkey’s jaw from which the water descends, one arm is raised upward and the other rests on his hip, while his left foot is placed on top of one of the defeated Philistines, whom we see lying on the ground around Samson. It brings out the hero’s Apollonian beauty, a beauty that also becomes a symbol of his moral strength, his valor as a leader, and his faith in God, just as the nudity becomes a symbol of the power of Truth that defeats God’s enemies. It is precisely this extraordinary beauty that helps to dilute the heroism of Samson’s figure in the sign of a sought-after grace: the victorious Samson, has, moreover, written Andrea Emiliani, one of the leading scholars of seventeenth-century Bologna, “is an operant symbol of a hybrid and anti-heroic venusty, raised to the sky as an idea of culture and grace : of grace and culture are cloaked, in the fall of an evening immersed in silence, the fallen bodies, or asleep in the bosom of a most sweet death.”

Although Guido Reni was the principal standard-bearer of Bolognese classicism, and thus inclined to create idealized figures, he was also a painter with a remarkable mastery of the study of anatomy and the human body, an aspect that is evident not only in Samson the Victorious but also in other, seminal works. Indeed, there are many paintings that offer evidence of this quality of Reno’s painting, such as the Nessus Abducting Deianira, a work preserved in the Louvre, or the Saint Sebastian in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna. A further significant example is the Magdalene with two angels, now in a private collection after it was sold in April 2008 by the Dorotheum auction house in Vienna: note the exceptional care and vivid realism with which Guido Reni paints the skull, a symbol of penitence. Looking at these works we can clearly perceive the attention Guido Reni paid to the study of the parts of the human body, and thus we can infer that the artist had a certain interest in science, probably nurtured by the fact that in Bologna, at the end of the 16th century, the great naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi was active, who set up an important collection of animals, plants and minerals and who certainly helped to give a considerable boost to scientific activity in the city of Bologna, reflections of which can perhaps also be seen in Guido Reni’s painting.

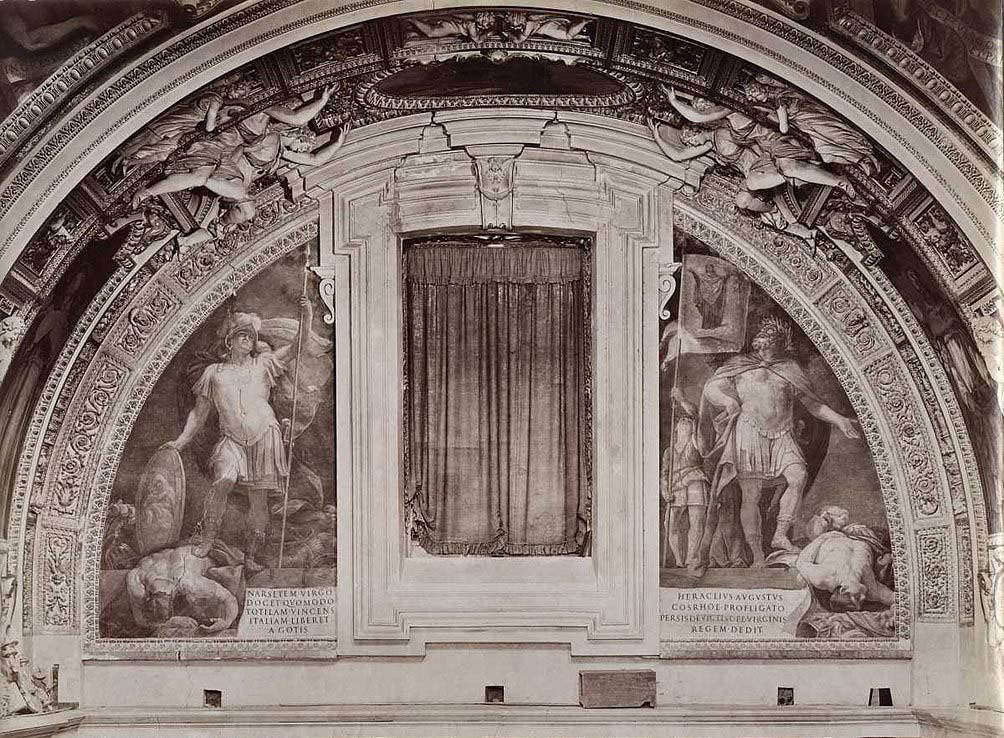

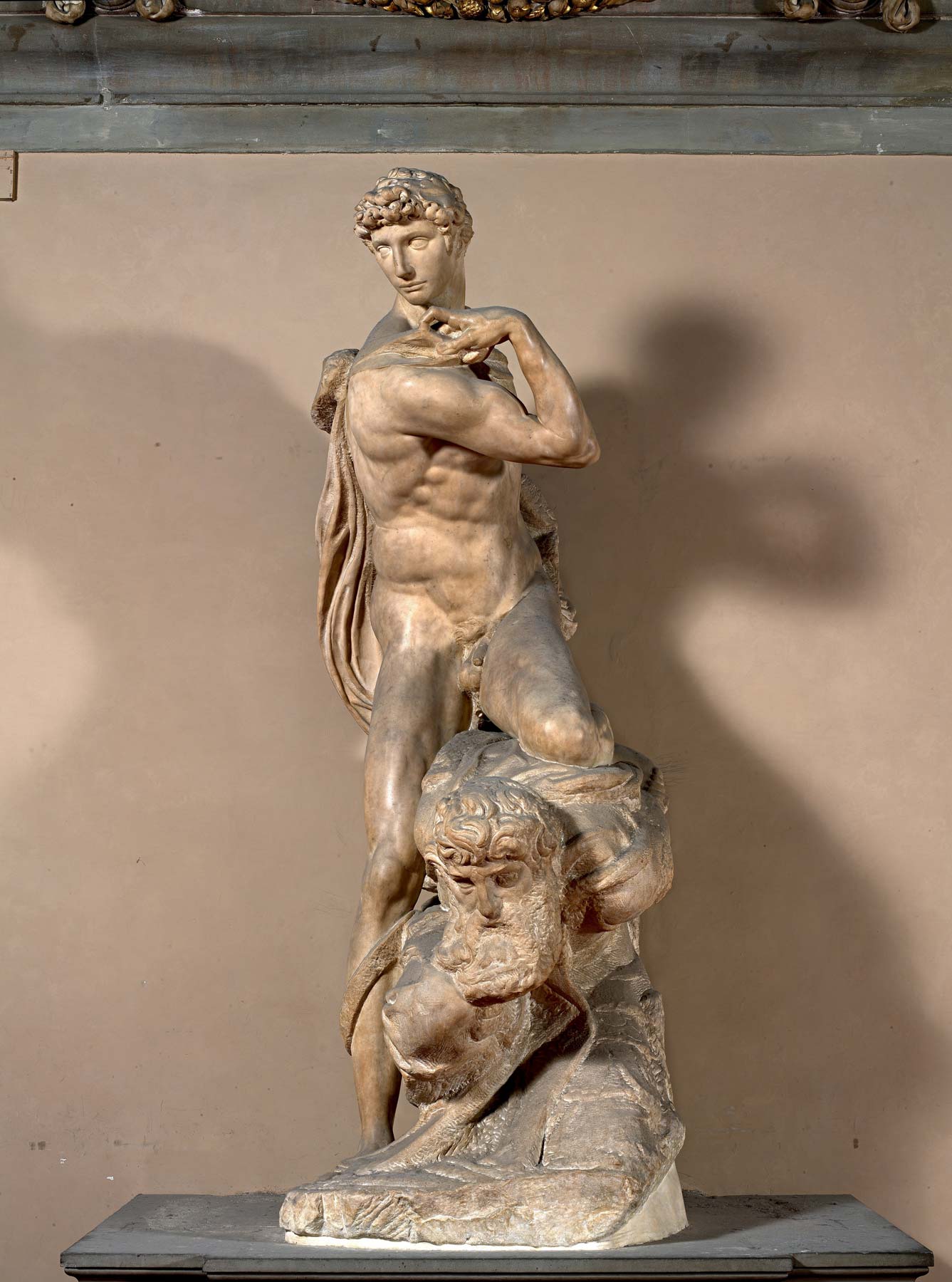

As for the possible models that might have inspired the victorious Samson, we can start, first of all, from classical statuary. In fact, the pose of Guido Reni’s Samson is inspired by that of the celebrated Apollo of the Belvedere, a Roman copy of a bronze by the Greek artist Leocare discovered at the end of the fifteenth century and later placed in the Cortile del Belvedere in the Vatican, while the left arm resting on his side retrieves that of the Laocoon group. Mention could then be made of a work by Michelangelo, the Genius of Victory, a 1534 sculpture currently preserved in Florence at the Palazzo Vecchio, from which the Bolognese painter is said to have taken the pose of the leg resting on top of the defeated enemy. After all, Guido Reni was familiar with the works of Michelangelo: starting in 1600, in fact, the painter often went to Rome, and in the capital of the Papal States he also stayed for a long time, that is, until 1614, the year of his final return to Bologna. In Rome, Guido Reni had important commissions but he also had the opportunity to study closely the works of the major Renaissance artists as well as of the great contemporaries, Caravaggio above all (without the study of Michelangelo Merisi’s work, one could not explain certain elements of the Crucifixion of St. Peter preserved at the Pinacoteca Vaticana, which was made between 1604 and 1605 and shows obvious similarities with the counterpart painting made by Caravaggio for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome). Guido Reni then takes up works of his own: Samson’s pose is the same as that of Narsete vittorioso su Totila painted a few years earlier, in 1612, in the Cappella Paolina of the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (one of the important commissions referred to), while the two Philistines lying on the ground recall the children in the lower left corner of the Strage degli innocenti, a work of 1611.

Antiquity, in the work of Guido Reni, is filtered through the example of Raphael, who, like Guido Reni, was led by the inspiring principle of ideal beauty (for his contemporaries, moreover, Guido Reni was a kind of new Raphael), and if Raphael made antiquity modern, in the same way Guido Reni made the Renaissance modern, rereading it through the contemporary achievements of Carracci and Caravaggio, thus reaching, more often than one might imagine, heights of unexpected naturalism, which, however, is not confused with reality and is always diluted by that crystalline, harmonious, terse language that is proper to Reni’s painting. According to Cesare Gnudi, no artist in the seventeenth century had understood Raphael more than Guido Reni, and the modernity of his classicism also lies in the more “filtered and literary” ways that were typical of all those artists eager to return to classical rules in times of crisis in order to make room for a measure in which beauty could return.

“If the refrain of the previous generation had been that every revolution imposes a return to nature,” Andrea Emiliani has written, “Guido’s proposal is that of a solid cultural rule, of a poetic norm capable also of returning to face an ancient problem, that of the universality of language, which precisely from Rome was moving.” Guido Reni’s program was thus different from that of Ludovico Carracci (who looked at the everyday) or that of Annibale Carracci (in whose works classicism, alien to nostalgic sentiments, nevertheless aimed at truth): his painting is filled with a limpid idealism that admits openings to naturalism in order to bring to life that “neo-Platonic theater of nature” in which, quoting Emiliani again, “the declared, irreplaceable goal of virtuous beauty is preparing to break through.”

The victorious Samson, despite its peculiarities and modernity, remained “without a following in the Bolognese painting milieu, which at these dates was predominantly following the style of Ludovico Carracci”, as scholar Giovanna Degli Esposti has written, “and was therefore unable to understand its peculiar poetic reality, and Malvasia himself, for that matter, limits himself to praising its drawing without, moreover, devoting much attention to it.” Still, this substantial isolation of perhaps the most extraordinarily classical work in Reni’s repertoire should not move one to surprise, just as it is not strange that “commercial” success, so to speak, arisen more for the Carracci than for Guido Reni. On the occasion of the first, important exhibition on Guido Reni, curated by Cesare Gnudi and Gian Carlo Cavalli in 1954 in Bologna, in the halls of the Archiginnasio, Cavalli himself started precisely from the victorious Samson to dwell on the causes of such isolation, at a time when theartist was reinforcing his classical idealism by aiming “fascinated by the secret harmony of ancient marbles, at a statuesque world in which the relationship with nature could find an absolute measure.” Fact is that the artist proposed a “literate painting filled with ’style’” that appealed to sophisticated clients with an art that was born entirely in the mind and was proposed “in times not classical but of Counter-Reformation”: it was, however, a painting always sustained by a “conscious meditation, inclined to operate in rational forms and reflected within the life of feelings.” And today we recognize her among the most advanced peaks of her era.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.