Human beings are constantly and auburnly searching for something throughout their lives, hoping that this something will leave even an insignificant scratch in the world. We want to be remembered: there are those who seek fame, those who seek full and boundless happiness, and those who, on the other hand, seek such blinding light and darkness that they leave behind half-tones. And it was precisely these fleeting gleams and tearing darkness that were hunted down by Édouard Manet (Paris, 1832 - 1883) as he found himself trapped in the search for his way. The now well-known “father of modernism” was initially a simple painter from a bourgeois background who embarked on his path with endless difficulties and equal complications: He began exhibiting, starting in 1861, at the official Salon, that of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, although the works that were accepted to him were mainly those echoing Velázquez and his Spanishate style, which, at the time, was extremely popular. While aiming for the grandeur of the official salon, Manet decided to keep open a small window that would allow him to express himself with more freedom: that of the private one.

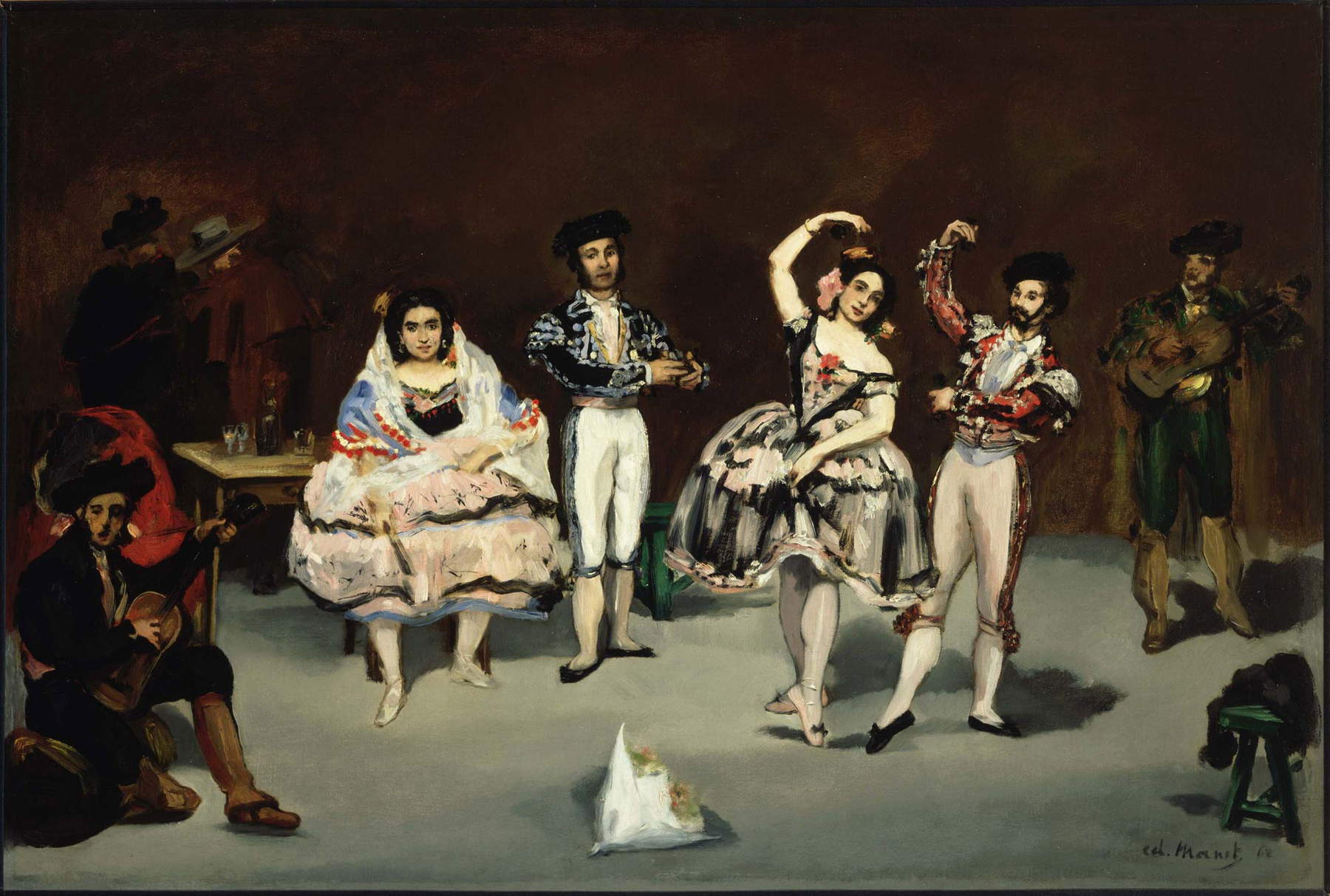

The gallerist Martinet exhibited, until 1863, paintings by Manet including the Spanish Ballet of 1862, but mostly his paintings explicitly devoted to modern life that until the 1970s were never shown at the Salon. In his biography Souvenirs, Manet’s lifelong companion Antonin Proust wrote, “His brief sojourn in sunny countries kindled a conception in which everything appeared to him with a simplicity that Thomas Couture did not understand...He removed half-tones altogether. He was constantly seeking the immediate transition from shadow to light.” The irreverent artist, although he found mere academic discipline inadequate and mortifying, worked at the studio of Thomas Couture (Senlis, 1815 - Villiers-le-Bel, 1879) for six years, well aware that his works were highly prized by the intelligentsia of the time and, above all, were the ones that entered the coveted Salons.

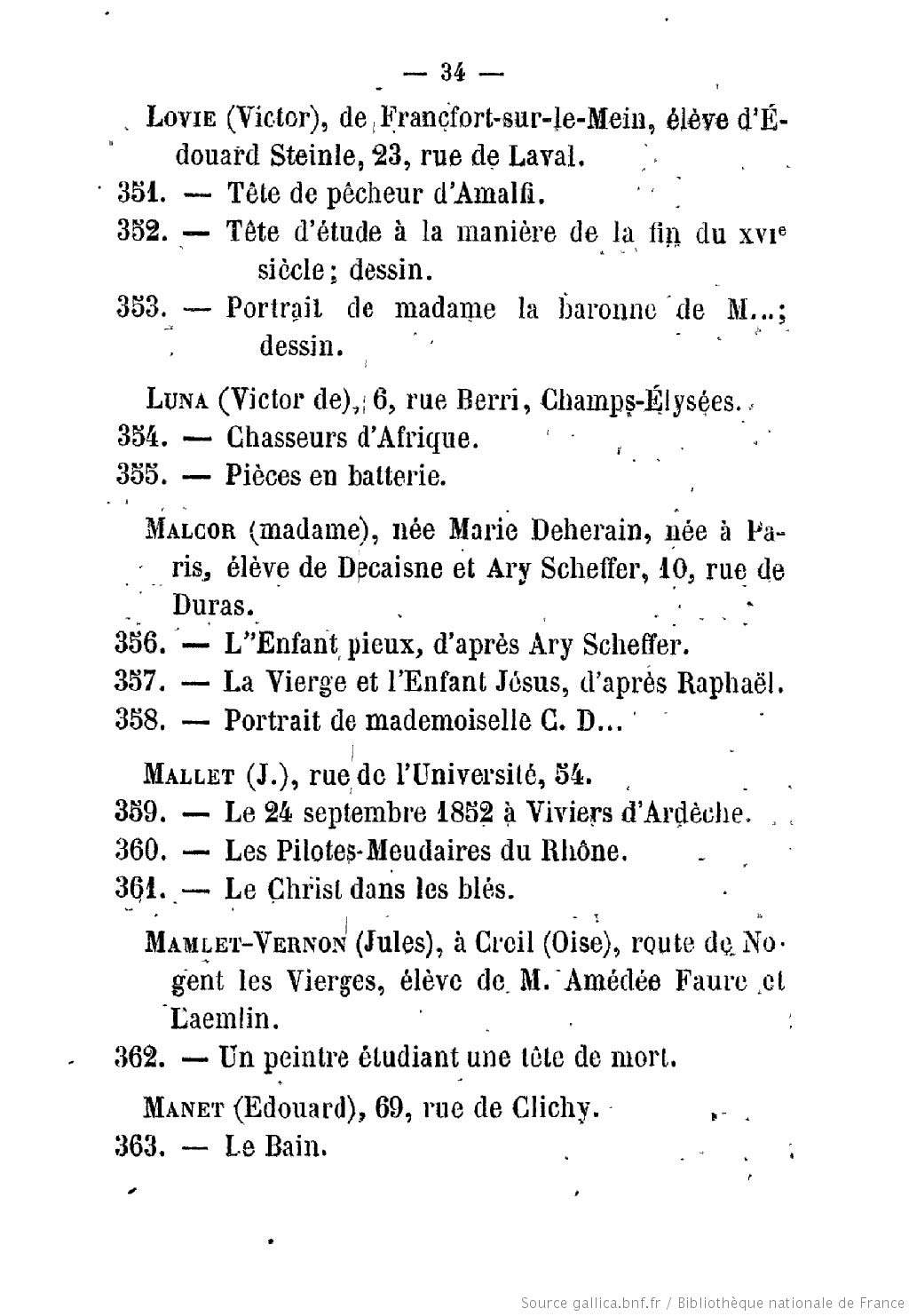

Although he was something of an “enfant terrible” of his time, a painter who seemed to reject tradition by painting hastily and even unfinished and carelessly, Manet wanted to be accepted and continued to compete for official recognition, constantly submitting his works to a jury that almost never found them aesthetically acceptable. And in 1863 he submitted, under the title Le bain ( “The Bath”), a large canvas now known as Le déjeuner sur l’herbe ( “Breakfast on the Grass”). It was a painting of a size usually reserved for works of the historical genre and had been conceived as the central part of a triptych, a flag-painting(tableau-drapeau, the term used at the Salon to refer to the painting that occupied the center of a wall) that featured on its sides two subjects of the Spanish genre: a portrait of a young man in the costume of Majo and a portrait of a young lady in the costume of Spain, both from 1862.

The work was rejected. Unfortunately, since no minutes were being taken, we have not been given a basic means of understanding why this work was excluded, but that same year, and for the first time, the multitude of rejected works led Napoleon III to open the Salon des Refusés, the salon where works rejected at the Salon were displayed. And so, Manet’s work was displayed in the new halls in the Palais de l’Industrie in the retrospective of horrors (or at least those that were considered such), rejects, and eternal rejects. This second exhibition, the Salon of the Rejected, attracted a flood of visitors who were intrigued by modern painting but little prepared for what they might discover. And they would have discovered paintings such as Whistler’s Symphony in White , Fantin-Latour’s La féerie , and especially Manet’s Breakfast on the Grass.

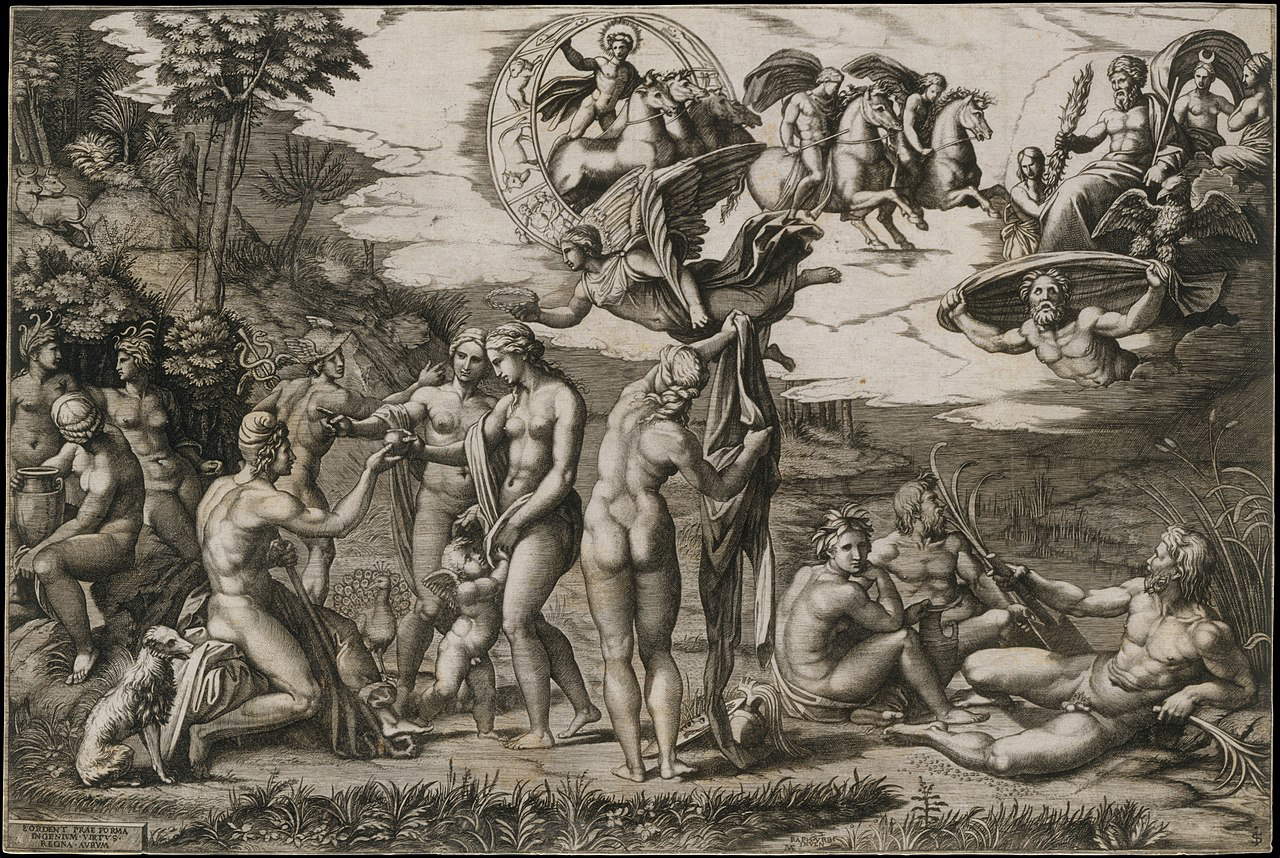

The artist here showcases a undressed woman looking, nonchalantly, toward the viewer while framing her face with one hand. The model is Victorine Meurent, a worker in Montmartre. Beside and in front of her are two students, one a medical student and the other a law student, fully dressed, intent on conversing with each other while, in the distance, another woman in petticoats bathes her legs in a stream. A seemingly simple scene representing only a breakfast, or rather an outdoor lunch, exposing the vices of the bourgeoisie of the time. Yet it was not until 1904 that it was discovered that the main group, in addition to declaring a continuity with Titian’s Country Concert, referred to the academic exercise of copying by engraving: specifically, from Marcantonio Raimondi’s print of Raphael’s Judgement of Paris (1513-1515), a fresco that has since been lost. Manet takes the three main figures and reinvents them. Instead of river gods and nymphs he presents modern nineteenth-century Parisians enjoying a picnic. It is not known why contemporary reviewers did not talk about it, since Raimondi’s work was well known and at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts it had been included for twelve years in a row as an examination paper for copy from engraving.

Yet, although such an art-historical pedigree can, very often, vouch for an artist’s culture, in this precise work it seems to emphasize even more the distance between Manet and the sixteenth-century sources. The idea of seeing two clothed men conversing with a woman who is not naked, but simply undressed, extremely mischievous, and overwhelmingly seeking the viewer’s gaze, was something shocking to the artist’s contemporaries. The deep disturbance was emphasized even more by the explicit sexual references such as the flying bird and, above all, by theinexplicability of the scene: there is no narrative in this work that can explain the contrast between the woman and the men, the former’s disinterest, the lack of modesty. The opposite happens than in any traditional painting where the models become nudes, usually mythological figures. Here Manet starts with the precise reference model (Raphael’s nymph) and deliberately chooses to overturn the canons of nude use. He takes a nude and beautiful nymph and strips her naked, making her a prostitute, and alluding to a dissolute and unspoken, hidden life.

The figures are set in a forest that historians have identified as the Bois de Boulogne, known precisely for the walks of prostitutes, or Gennevilliers, a river port on the Seine located ten kilometers northwest of Paris, where the Manet family owned land.

Nevertheless, the work’s eerie lighting has often been compared to a scene illuminated by camera flashes, which accentuate contrasts and flatten the figures in the foreground. And Le déjeuner sur l’herbe was branded by contemporaries as a scabrous, indecent and scandalous work, and the reasons that contribute to its being so are many. For example, also noteworthy is the Titianesque still life in the foreground, improbable since peaches and cherries ripen in different seasons, and especially the sharp, luminous figures silhouetted perfectly against the dry background reminiscent of a photographic studio backdrop. It was, therefore, not only the content that caused endless controversy, but also, and above all, the artist’s technique and the deliberately crude drafting of colors, the chromatics characterized by violent contrasts between light and shadow that abolish chiaroscuro. Having studied with Thomas Couture, Manet was familiar with the academic methods of image construction, the use of chiaroscuro: yet he chose not to apply the rules by flattening the forms and emphasizing the surface of the canvas. Thus he began to create women who look like corpses, dipped in a blanket of chalk, spaces with flat and anything but traditional perspective; he began to eliminate gradations of tone, leaving abrupt juxtapositions of light and dark.

Édouard Manet was a man torn between two worlds and eternally poised between them: the bourgeoisie, to which he belonged by blood, and the poorer, truer and more disenchanted Paris. He invented a new language for which he was never really accepted, except by the outcasts and the strange Impressionists in whose exhibitions he never participated. Manet wanted to be great, he wanted to be accepted and remembered, but we should always be very careful what we wish for because, as Oscar Wilde wrote in 1895, “when the gods want to punish us they answer our prayers.”

The author of this article: Francesca Anita Gigli

Francesca Anita Gigli, nata nel 1995, è giornalista e content creator. Collabora con Finestre sullâArte dal 2022, realizzando articoli per lâedizione online e cartacea. à autrice e voce di Oltre la tela, podcast realizzato con Cubo Unipol, e di Intelligenza Reale, prodotto da Gli Ascoltabili. Dal 2021 porta avanti Likeitalians, progetto attraverso cui racconta lâarte sui social, collaborando con istituzioni e realtà culturali come Palazzo Martinengo, Silvana Editoriale e Ares Torino. Oltre allâattività online, organizza eventi culturali e laboratori didattici nelle scuole. Ha partecipato come speaker a talk divulgativi per enti pubblici, tra cui il Fermento Festival di Urgnano e più volte allâUniversità di Foggia. à docente di Social Media Marketing e linguaggi dellâarte contemporanea per la grafica.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.