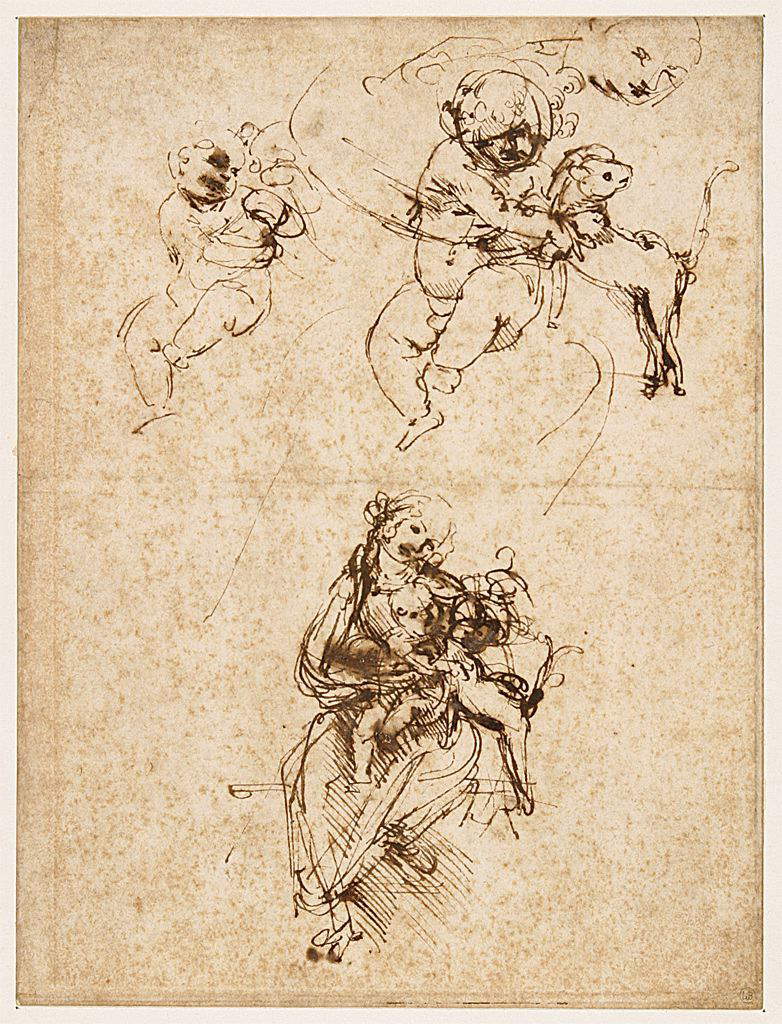

Among the vast body of drawings left to us by Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) there are not only studies on the human body, complex engineering projects or ideas for futuristic machines: a significant part of the corpus of his drawings is in fact dedicated to studies on animals, and among these there is no shortage of cats either. In fact, we know that the Tuscan genius had begun work on a Madonna of the Cat, which, according to what we know, never became a finished painting: the only traces of this singular work can be found in the drawings that attest to the study of a composition with the Madonna, the Child and a cat clasped in Jesus’ arms. The probably oldest drawing is kept in a private collection in New York and according to Carmen C. Bambach, an expert on Leonardo da Vinci drawings, it would be a work from the second half of the 1770s, because of the Virgin’s features and three-quarter pose, which still denote a strong dependence on the art of Verrocchio, an artist of whom Leonardo had been a pupil. In the drawing, the Virgin holds the infant Jesus in her arms and he, in turn, clutches a cat. Other drawings in which Leonardo experiments with the same composition are known: at the Musée Bonnat in Bayonne, France, we find one in which the artist tries a different scheme (drawing three studies), with the cat standing on its hind legs and resting its front ones on the Virgin’s left knee. Even more detailed is a sheet drawn on both sides, and kept in the British Museum: on the recto, that is, the front side, the pattern is quite similar to that of the New York sheet, while on the verso, the back side, the cat shifted to the right and standing on its hind legs returns, as in the Bayonne sheet.

Then there is a further drawing, dating from a period around 1478 according to the scholar Pietro Marani, preserved in the Uffizi: here, Leonardo’s idea seems to have already reached a rather advanced point, at least in appearance, since his focus is mainly on the figure of the Child. In this drawing, Marani himself has well explained, Leonardo takes his cue from Verrocchio’s Madonnas to which he places “a Child, of great proportions, who, attempting to hold a cat, becomes dangerously unhinged to the point of unbalancing the whole group to the right.” However, Marani points out, “the Virgin initially does not seem to connect well with this movement and remains a static observer of what is literally rushing out of her lap, since her timid gesture of holding back the Child, does not seem to produce any contrast or reaction of forces, or even a consequent expression. In fact, the verso of the Florence drawing focuses on the Child alone, even more unfortunate resulting in the timid hint of the Virgin’s arm under (rather than above, as shown by the recto drawing) the Child’s right leg.” It is curious to note that in the Uffizi sheet, as was the case in the one in the British Museum as noted by Bambach, Leonardo traced the Child by tracing the one on the other side of the sheet, simply exposing it to the light and then tracing the drawing with pencil.

Again, the British Museum keeps a sheet, drawn on the recto and verso, where we see sketches for a child playing with a cat on the back side, while on the other side of the sheet still studies for a Madonna of the Cat, and then again a child with a cat, and a cat alone. Surprising is the naturalness of the poses: according to Carmen C. Bambach these are, in this case, studies drawn from life, and one must therefore imagine Leonardo who, with his notebook and pen, was following a child playing with a cat, thus lavishing himself in a “very modern way of drawing,” the scholar noted. A kind of ante litteram brainstorm by which the artist was merely fixing his ideas on the paper.

There are thus several experiments by Leonardo on the theme of Our Lady of the Cat. However, it is difficult, if not impossible, to sequence the various sheets to try to understand what Leonardo da Vinci had in mind. What might have inspired the artist? Works in which the Madonna and Child appear together with a cat in late 15th-century painting are very rare, but they are there. In Vigevano, in the church of the Madonna della Neve, there is a still inadequately studied fresco in which the Child is seen clutching an animal in his hands: a well-established local tradition has it that the little beast is a cat, and the imagination of the inhabitants has often gone so far as to suggest the idea (completely unfounded) that the work, once in the church of Santa Maria dei Pesci (so called because it was located near the city’s fish market, then demolished), even inspired Leonardo. There are, however, paintings where the animal is unmistakably a cat: we see the feline, for example, in a Madonna and Child attributed to Giovanni Martino Spanzotti, preserved at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and dating from around 1475 according to the museum. Here the cat is depicted trying to undermine the goldfinch that the Child Jesus holds by a thin thread, a reference to the Passion (the red stain on the snout of the goldfinch is symbolic of the blood shed by Christ on the cross): with the cat, therefore, the devil enters the scene, who takes on the animal’s guise to tempt Jesus and, consequently, all humanity, to try to make it fall into sin.

Another cat, probably a little later than Leonardo’s drawings, is the one we observe in the Madonna and Child and a Cat attributed to the Master of the Pala Sforzesca or his circle, and where, however, the iconography is completely different from those in the paintings mentioned above: here, in fact, the cat is held on a leash by the Child. And according to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, the institution that preserves this painting, the meaning could even be opposite to that of the panel attributed to Spanzotti: since in fact the cat hunted snakes and animals considered harmful to the house, it could even be considered a “defender of the good,” the museum’s catalog reads. But there are also other explanations according to the museum: the cat could be a reference to a popular Christian legend that a cat gave birth at the same time that Mary gave birth to Christ. But it could also be a heraldic emblem of the family or person who commissioned the work. Reference to this popular legend is also what Carmen C. Bambach, in the catalog of the Leonardo Da Vinci: Master Draftsman exhibition held in 2003, calls in to explain why Leonardo had tried his hand at the Madonna of the Cat theme: it would thus be more properly a Madonna of the Cat (the same subject that decades later Federico Barocci would choose for one of his most famous paintings).

The most direct result of Leonardo’s studies on the subject to date seems to be a panel, preserved at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan and variously assigned to artists in Leonardo’s circle (it could be Cesare da Sesto, or the Spaniard Fernando Yañez), a Madonna and Child and the Little Lamb: the composition faithfully echoes the cue traced by Leonardo on the New York sheet, although a lamb, a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, is inserted in place of the cat. Yet X-rays taken of the painting have shown that the author of the painting had previously depicted precisely a cat, before changing his mind and covering it with the figure of the lamb. But even with the naked eye one can see that, with the snout removed, the animal is depicted in a pose that is much more typical of a cat than of a lamb (and then, one need only look at the tail, which is also identical to that of a feline).

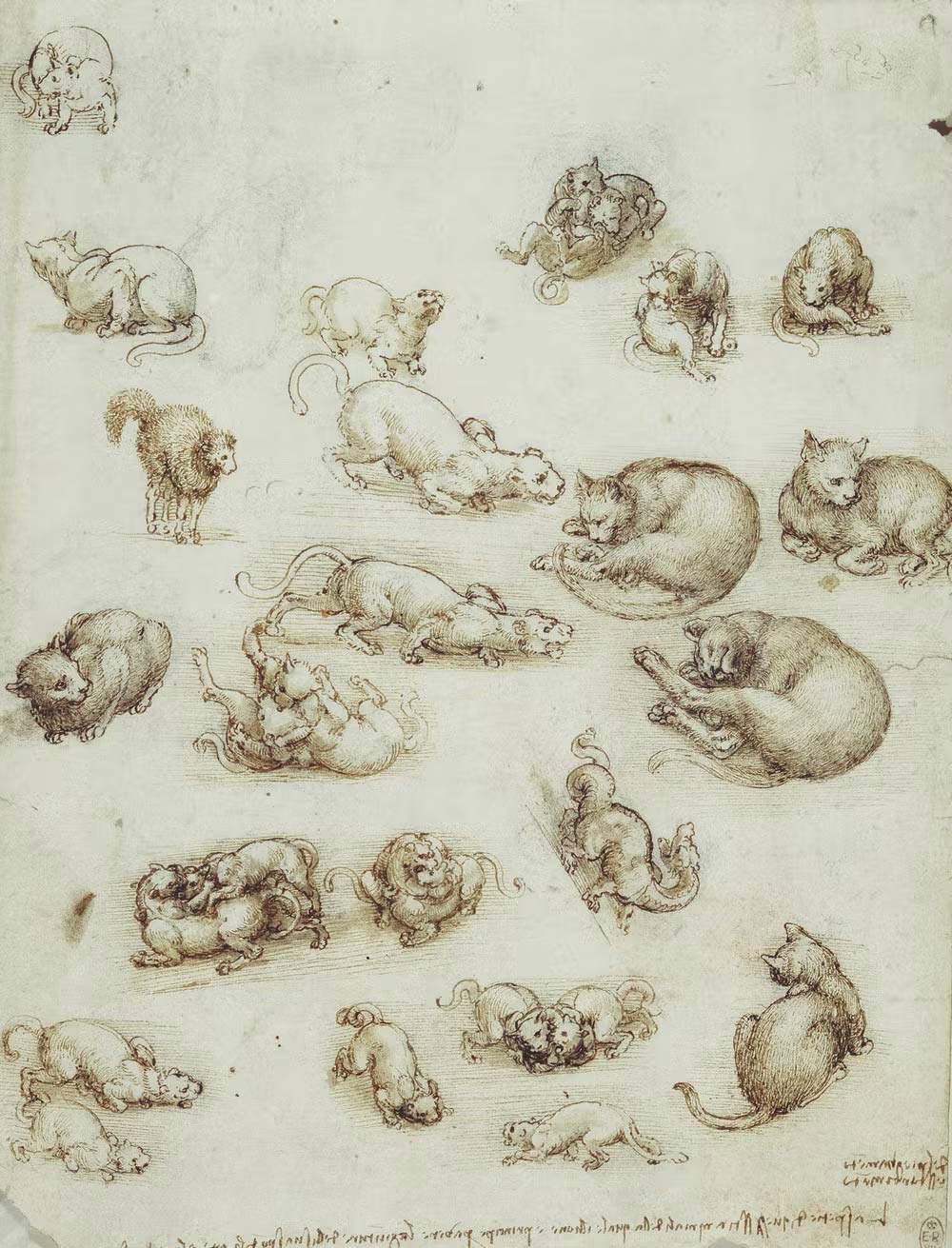

Then there is a further product of Leonardo’s interest in cats, and it is perhaps the most famous: a sheet preserved at the Royal Library in Windsor where the Tuscan artist studied various poses of the most common of felines. Leonardo fills the sheet with some 20 cats caught in different attitudes and states of mind. There are cats playing, cats fighting or facing each other, frightened cats, cats looking around suspiciously, cats licking each other, cats lying down, cats who are hunting, and cats simply standing still watching. This is a sheet that has nothing to do with the studies on the Madonna of the Cat, not least because it is many years later (according to experts, it can be assigned to a period between 1513 and 1517, so we are about thirty years away from the sheets seen above): in the lower right corner, in fact, some inscriptions appear (“del pieghamento” and “esstendimento”) that make it clear that Leonardo made drawings here with the declared aim of studying the animal’s movements, which “strongly confirms his intention,” wrote Carmen C. Bambach, “to write a treatise on animal movements in his later years.”

Bambach calls these studies of cat movements “delightful”: “the little drawing of a frightened cat standing upright on its paws, with its back arched, its fur upright, and its tail thick, is alone worth a thousand words.” We do not know whether Leonardo studied his cats live, as would seem by observing the immediacy of his sketches, or most of them. It is likely that some of the motions were traced in direct view, while for some of the more finished, often replicated drawings, Leonardo allowed himself longer meditations. Note how a little dragon also appears in the sheet, in the lower part: the study of real animals was in fact also used to imagine the movements of fictional animals, and in this case the dragon is not so dissimilar compared to the many cats that surround it.

Beyond the curiosity that these drawings may arouse, they are nonetheless fundamental works in Leonardo da Vinci’s career. This is especially true of the sketches of the Madonna of the Cat, whose role was further clarified by Bambach on the occasion of the major exhibition on Leonardo da Vinci held in 2015 in Milan’s Palazzo Reale. Indeed, these drawings constitute, the scholar wrote, “the first example that illustrates in a relatively complete way the methods used by Leonardo to work out a composition. These sketches are executed with splendid spontaneity and offer a mine of compositional ideas for posing the figures. The young artist’s brilliant mastery of the use of pen, ink and watercolor is evident in the vividness of the contours and reinforcing lines of the moving figures, as well as in the sketchy modeling, with touches of watercolor suggesting the three-dimensionality of the forms.”

We do not know for certain whether Leonardo had in mind to translate his ideas for a Madonna of the Cat into a finished painting, or whether these were merely tests to study the arrangement of the figures in a composition, or to try his hand at chiaroscuro effects (keep in mind that Leonardo was in his early twenties at the time). Nevertheless, singular and definitely significant traces remain in the path of one of the greatest artists ever.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.