“Every attribution contains a kernel of truth,” asserted Federico Zeri back in 1961 when he gave to the press (with a meaningful dedication to Bernard Berenson) his exemplary lesson in art-historical method contained in Two Paintings, Philology and a Name. Here the unforgettable scholar had tried to contextualize with customary lucidity the so-called Barberini Tables starting from the attributive hypotheses that had preceded his analysis, in some ways very similar to the conduct of any judicial-type investigation: apart from the cases (a “very small percentage”) that lead of “first cast” to the definitive solution, Zeri observed that artistic attribution is nothing more than the “attempt to solve a given problem by means of the knowledge possessed by the epoch to which the scholar who proposes them belongs.” The passage of time, increasing cognition with the discovery of new details, broadens the boundaries of the field of research and points “authentic philologists and connoisseurs” to new perspectives and solutions, without, however, “undoing that immutable quantity of truth on which others, with full reason with respect to the times, had founded themselves” (Federico Zeri, Due dipinti, la filologia e un nome. The Master of the Barberini Tables, 1961, ed. Milan, 1995, p. 11).

|

| Master of the Barberini Tables, Nativity of the Virgin (c. 1460-1470, 1467?; oil and tempera on panel, 144.8 �? 96.2 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

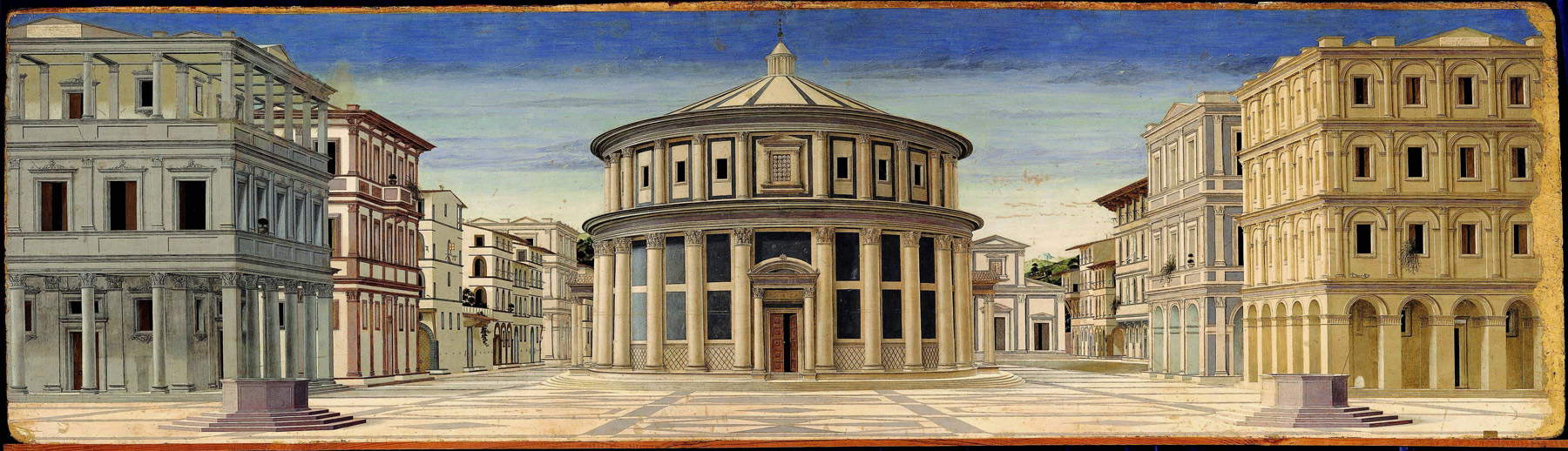

Starting from the meager known documentary data on the personality of Giovanni Angelo da Camerino, Zeri then proposed that he was the “Master of the Barberini Tables,” a conventional name coined in the early twentieth century by Adolfo Venturi and to which Richard Offner had linked, in addition to the Barberini Tables(Nativity of theVirgin, Metropolitan Museum, New York, and Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which came from Urbino and were kept in the Barberini’s Roman collection until 1935, when they emigrated overseas), two other paintings to which Zeri himself juxtaposed four further additions. The analysis of the nucleus thus constituted of those eight paintings allowed the scholar to remark the complex culture of the author of the thus reconstructed corpus: the stylistic relations with Giovanni Boccati, already understood by Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle; the links with the Florence of Filippo Lippi and Domenico di Bartolomeo Veneziano but also with Piero della Francesca and Giovanni di Francesco; the Albertian memories evident in the painted architectures of the Barberini Tables, for which the famous Ideal City (Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche) is also often referred to.

|

| Central Italian painter, Ideal City (1480-1490 ?; oil and tempera on panel, 67.7 x 239.4 cm; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche-Palazzo Ducale) |

This is not the occasion to go over in detail the further developments that arose from Zeri’s seminal study, although it must be said that later critics have not agreed on that proposed identification, leaning rather toward the Urbino Dominican Fra’ Carnevale (or rather Bartolomeo Corradini, or della Corradina, active in the Florentine workshop of Filippo Lippi), a name already suggested at the end of the 19th century by Venturi and to whom a “monographic” exhibition was also dedicated a few years ago(Fra Carnevale. A Renaissance Artist from Filippo Lippi to Piero della Francesca, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera, 2004). The fact remains that to this day neither Giovanni Angelo da Camerino nor Fra Carnevale’s works are known to be signed or documented, although useful information exists for both of them to place them with some certainty in the same artistic, cultural and chronological sphere, while the historical nucleus of paintings stylistically approachable to the Barberini Tables, with its precise cultural coordinates well delineated by Zeri, is in any case now accepted as substantially homogeneous.

|

| View of the Rocca Sforzesca in Dozza, Metropolitan City of Bologna. |

To the same 1961 as Two Paintings, Philology and a Name by Federico Zeri dates the assignment of the singular Family Portrait of the Castello Malvezzi-Campeggi or Rocca Sforzesca (Dozza/ Città Metropolitan City of Bologna) to Pier Francesco Cittadini (Milan, c. 1613/1616-Bologna, 1681),known as the Milanese because of his origins, even though much of his activity had taken place in Emilia, at the Este court and in Bologna, in the circle of the great Guido Reni, a master whose pupil he was from about the early 1630s. So an artistic matter of about two centuries later than the facts studied by Zeri in the basic methodological reading briefly recounted above. Exactly forty years later, in 2001, a “daring” exhibition event was held precisely around the Family Portrait, with the intention of certifying its attributive shift from Cittadini’s catalog to that of Lorenzo Pasinelli (Bologna, 1629 - 1700), a Felsine painter belonging artistically to the next generation, that of the followers and not direct pupils of Reni, although the intention was concealed under a more ambitious program argued even in the significant title of the exhibition(Figure come il naturale. Il ritratto a Bologna dai Carracci al Crespi, edited by Daniele Benati, Dozza, Castello Malvezzi-Campeggi, 2001), in which there was no shortage of other attributional theories liable to careful revision.

|

| Pier Francesco Cittadini known as the Milanese, Family Portrait (ca. 1645; oil on canvas, 265 x 360 cm; Dozza, Rocca Sforzesca) |

Unlike the theme addressed in Zeri’s small volume, in this case the names of the painters involved are two (Pier Francesco Cittadini and Lorenzo Pasinelli) for a single painting, Family Portrait: starting in the 1960s, the frank and approachable characteristics of the large painting and its not inconsiderable presence in the Emilia-Romagna territory had appeared to studies as persuasive signs useful for an irreproachable philological reading, since ancient sources recall the young Cittadini as a pupil in Milan of Daniele Crespi, an excellent portraitist as well as a religious painter. It had thus been reasonably thought that in the renowned Milanese workshop frequented also by the almost contemporary Carlo Ceresa(the best-known painter of “real” portraits in seventeenth-century Lombardy), Pier Francesco, before moving to Bologna to Reni, had matured similar stylistic orientations useful to justify his possible authorship not only for the large family group at the Rocca di Dozza, but also for a large number of effigies of basically Lombard-Ceresian culture that cannot be convincingly returned to Crespi or Ceresa. The art market, as is often the case, had ridden the wave, and the Cittadini portraitist’s catalog over the decades had expanded beyond measure, until new perspectives intervened to offer a possible different attributive solution for the large group effigy in question.

It is obvious that, as Zeri had well explained, this renewed point of view on the work could not under any circumstances have invalidated the immutable certainties on which previous scholars had based their reflections, but only expanded the boundaries of the field of research and, by enriching some of its details, indicated new possibilities for progress. Thus it was only apparently: in fact, what until the 1690s were almost unanimously considered stylistic evidence useful to justify the link with Pier Francesco Cittadini’s painting manner around 1650, were undermined by the cross-analysis of some documents concerning Lorenzo Pasinelli, who, between 1663 and 1664, turns out to have been in Rome a few months at the Marquis Tommaso Campeggi ’s (as witnessed by a letter from theartist dated December 8, 1663 addressed to his wife) and, in return for his hospitality, painted the “Portraits of the entire House of the Senator” of Bologna (a quotation that does not clarify whether the artist had made a series of individual effigies or a single depiction). In support of the latter historiographical indication intervened the connection with another source, similarly eighteenth-century, testifying to the existence of a large painting “at the Malvezzi house in Bologna” depicting the full-length portraits of what was contextually associated precisely with the depiction of the “Campeggi family” made by Pasinelli. Since the Campeggi and Malvezzi families were as much bound by rivalry as by close family ties that over the centuries led them alternately to the possession of fiefs and the castle of Dozza, where the large canvas with the family group has been preserved since the nineteenth century, it was thought that the latter was precisely the work executed in Rome by Lorenzo Pasinelli. Yet very problematic remained the stylistic aspect of the painting, which did not correspond well to the expressiveness of the Bolognese painter, always very balanced and of a classicist approach oriented to 18th-century neo-Mannerism since the late 1750s, characterized by elegant figures marked by happy theatrical attitudes and material type always light and flowing with light hues, not infrequently iridescent and iridescent, almost dissolved in light: all contrasting peculiarities compared to the static, fully seventeenth-century Lombard-style naturalism of that group portrait, which is distinguished, on the contrary, by its dense, sonorous, dark and heated chromatics, decidedly more consonant with the pictorial modes of Pier Francesco Cittadini between 1640 and 1650.

|

| Lorenzo Pasinelli, Risen Christ Appearing to the Mother (1657; oil on canvas, 670 x 390 cm; Bologna, Church of San Girolamo della Certosa) |

|

| Lorenzo Pasinelli, Portrait of a Child (ca. 1660-1670; oil on canvas, 67 x 52.5 cm; Bremen, Kunsthalle) |

The next step was the matching of the identities of the characters depicted: the consequent result was that, at the time Lorenzo Pasinelli painted all the characters of Casa Campeggi who were to be identified with the Dozza Family Portrait, the ages of the marquis, his wife and their ten children (seven females and three males) appeared to conform to those demonstrated by the twelve figures depicted in the painting at the time Pasinelli would have portrayed them: Tommaso Campeggi (1622 - 1689), was in his early forties in 1663-1664, and in his early thirties was his wife Ippolita Obizzi (1631 - 1680); their eldest daughter, Lucrezia Maria, was born in 1649 and was therefore about 14-15 years old, followed by Francesca Maria (1650, 13-14 years old), Orsina Maria (1651, 12-13 years old), Maria Eleonora (1652, 11-12 years old), Brigida Elisabetta Maria (1654, 9-10 years old), Antonio Domenico Maria (1656, 7-8 years old), Lorenzo Maria (1657, 6-7 years old), Annibale Tommaso Maria (1658, 5-6 years old), Maria Margherita (1659, 4-5 years old) and Felicia Maria Margherita (1661, 2-3 years old). At least two other children were born of the same marriage union, but after the family’s Roman sojourn: Giuseppe Maria Francesco, who came into the world in 1668, and Anna Maria in 1671, both in Bologna.

|

| Pier Francesco Cittadini known as the Milanese, detail of Family Portrait (c. 1645; oil on canvas, 265 x 360 cm; Dozza, Rocca Sforzesca) |

|

| Pier Francesco Cittadini known as the Milanese, detail of Family Port rait (c. 1645; oil on canvas, 265 x 360 cm; Dozza, Rocca Sforzesca) |

Thus all the problems of the proponents of the new attributive theory seemed resolved. However, in the enthusiasm of the reconstruction that was supposed to prove the extraneousness of Pier Francesco Cittadini from the making of the work and of almost all the portrait genre paintings previously traced back to him (e.g., the two preserved in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna), it was been neglected to do the “litmus test,” that trivial control test that we have all known since elementary school as a shortcut to verify the goodness of an arithmetic operation. It is true that it is not always possible to have a similar scientific type of feedback as well in the History of Art, but in the case of our Family Portrait, the “litmus test” had to be and could have been done before more than one misleading theory was popularized.

|

| Pier Francesco Cittadini called the Milanese, Portrait of a Child with Tray of Cherries and Pears (c. 1650; oil on canvas, 117 x 95 cm; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Pier Francesco Cittadini known as Milanese, Portrait of a Lady with Child (c. 1650; oil on canvas, 172 x 128 cm; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

From the outset, in fact, evident was an anomaly in the fact that two of Senator Tommaso Campeggi’s daughters bore the same name, a circumstance that should appear rather illogical even to researchers who have not honed archival practices. In this case, we are talking about the girls who were born in 1659 and 1661, baptized Maria Margherita and Felicia Maria Margherita respectively, already made to coincide with the two younger girls depicted within our portrait. In spite of the apparent irrelevance of the datum, it is thanks to it that I have been able to bring to light the real family situation of Marquis Campeggi, who in fact in July 1660 suffered the loss of one of his daughters, as we read in the Libro dei Morti of San Giacomo dei Carbonesi in Bologna, the district of the family’s residence, now preserved in the local l’Archivio Arcivescovile: the “Sig. Contessa Margaritta daughter of Ill.mo Sig. Senator Marchese Campeggi died in the Parish of S. Martino Maggiore at the age of eight months and was buried inside the Clausura delle RR. Nuns of the Most Holy Body of Christ.” In fact, when another girl was born the following year to Tommaso and Ippolita Campeggi, she was again given the name of her little sister who had died the previous year, Margherita (preceded by Felicia Maria), thus confirming the impossibility of two girls with the same name living together in the family.

|

| Pier Francesco Cittadini known as the Milanese, detail of Family Portrait (c. 1645; oil on canvas, 265 x 360 cm; Dozza, Rocca Sforzesca) |

Through this first simple biographical verification, the thesis of the convergence of our group portrait with the family nucleus of Tommaso Campeggi finally falls apart since, between 1663 and 1664, the nobleman from Bologna had only nine living children, and not the ten counted in the painting. For this reason it is almost impossible that the Family Portrait is the same one that Lorenzo Pasinelli painted in Rome at the turn of those two years.

But that is not all: it has already been mentioned that “at the Malvezzi house in Bologna” in the eighteenth century there was preserved “a large painting” depicting a full-figure family, probably coinciding precisely with the large painting we are dealing with: some perplexity should have been aroused from the outset by its iconographic identification with the Campeggi family, already proposed in the 18th century, since it would not make sense that such an image had been kept at the domicile of another noble family and not in the Campeggi palace. Following the trail of this other anomaly, I was able to discover that the offspring of Marquis Carlo Filippo Malvezzi (1595 - 1665) and his wife Ginevra Barbieri (?-1692), married since 1626, was quite substantial, similar to that of Tommaso and Ippolita Campeggi but a generation ahead: Elena Alessandra (b. 1627), Isabella (1628), Marsibilia (1630), Galeazzo Protesilao (1631), Fulvia (1632), Pantasilea (1634), Protesilao Vincenzo (1635), Maria Angela (1636), Emilio Maria (1639) and Laura Francesca (1640) were their ten children, three boys and seven girls, scaled just as in our group portrait. And this time the indispensable biographical verifications also confirm that these children were all alive in the mid-seventeenth century (unlike their two other little brothers, Maria Elisabetta, born in 1629, and Girolamo, in 1637, both of whom were alive for only two years), that is, in the same period in which the ’work when it was recognized to be stylistically consonant with Pier Francesco Cittadini’s production and his artistic approach, which synthesizes the austerity of early 17th-century Lombardy with the refinement of the Bolognese world of Reno.

In conclusion, if the identification of Carlo Filippo Malvezzi’s family in the twelve effigy figures, though highly plausible, is to be proposed with inevitable caution, on the other hand, the one that sees Lorenzo Pasinelli as the author of a work that cannot depict the family of Tommaso Campeggi in the early 1760s is undoubtedly erroneous. What remains available to scholars are the peculiar stylistic indications of the painting, its unquestionably Ceresian setting, strongly austere in spite of the meticulous sartorial description, all characters that conform to many paintings by Pier Francesco Cittadini, who in the light of current knowledge and stylistic and material comparisons can finally return to being considered as the credible author of both the canvas with the family group of Dozza and of other portraits, perhaps too hastily deleted from his catalog.

Note: The reconstruction of the issues addressed here, with due insights, documentary references and bibliography, is published in “Tactile Values,” 10-11, 2017/2018 (N. Roio, Two Painters, Methodology and a Painting: Pier Francesco Cittadini, Lorenzo Pasinelli and a Family Portrait, pp. 86-101).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.