“The story I want to share with you today is my personal challenge as an Iranian woman artist living in exile.” So begins the talk by Shirin Neshat (Qazvin, Iran, 1957), who was invited to give a talk as part of the TED Talks, the conference organized annually internationally with the aim of “fostering the spread of great ideas” so that everyone can better understand the big issues facing the world and help create a better future. It was 2010 and the artist was speaking at the first TED Woman ever organized to reflect specifically on how women, from every latitude and every generation, are today and will be tomorrow important drivers of change in shaping the world to come. The contribution Neshat brings is that of her own work, inseparable from her biography, and that of Iranian women who, according to the artist, have historically embodied political change in Iran. To them, as will be seen, the best-known part of his work is dedicated.

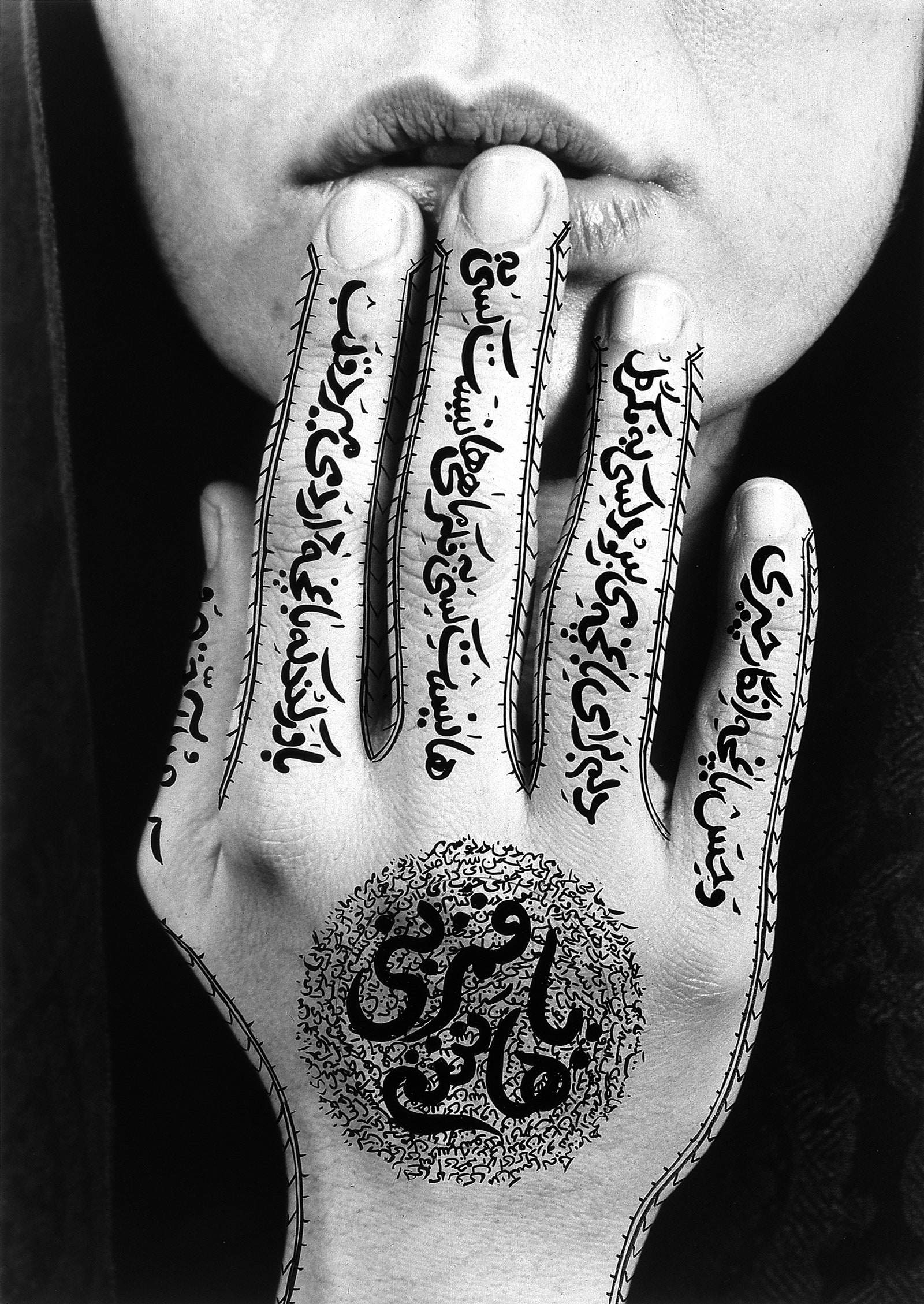

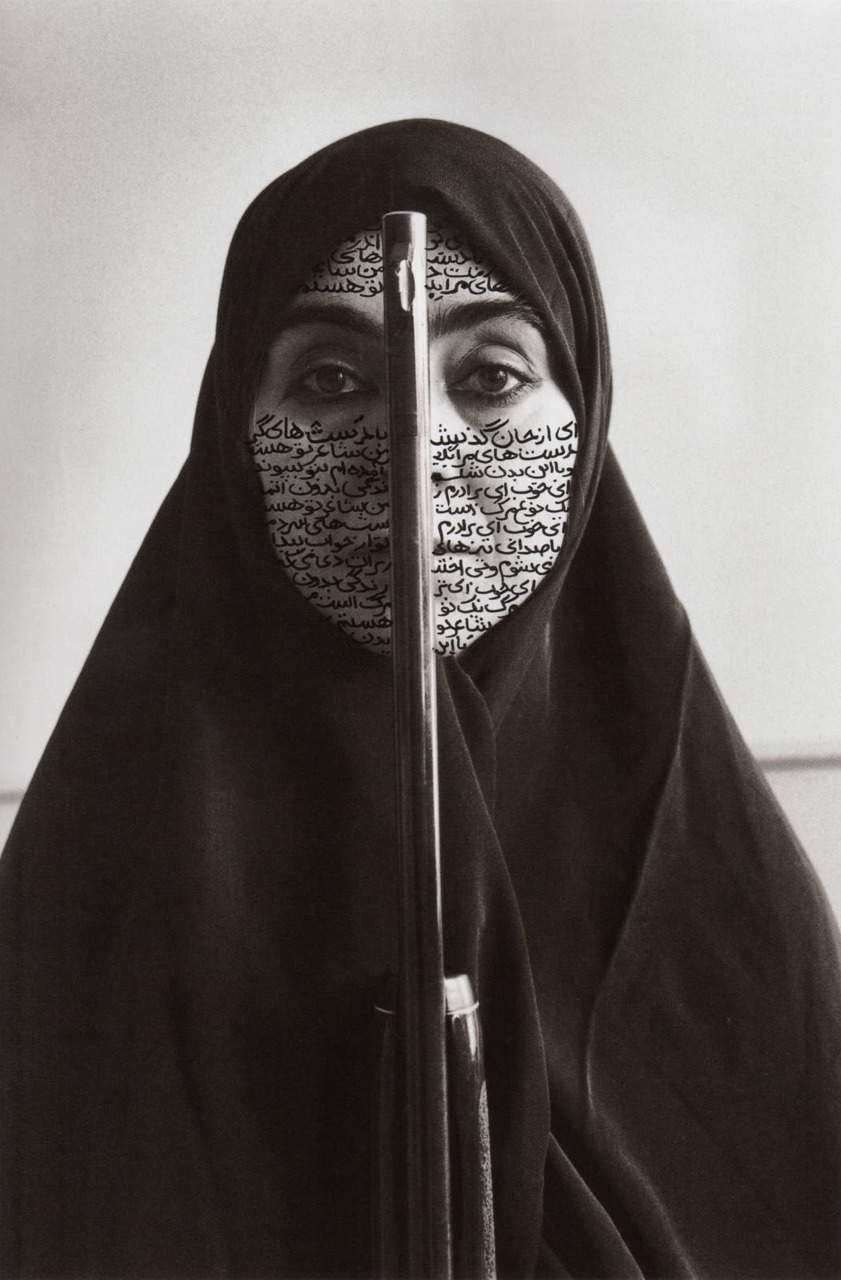

Women of Allah is the photographic series that Neshat made between 1993 and 1997 and is the result of a traumatic encounter. The artist, after leaving home at a young age to continue her studies in the United States (where she still resides permanently) returned home in 1990, after more than a decade. Iran had changed profoundly. In the aftermath of the 1979 revolution, the country was an Islamic Republic, a true theocracy with a dualistic political and institutional system that, even today, incorporates democratic and dictatorial traits. In response to this context, the artist feels a renewed communicative urgency and harnesses art as a weapon, as a form of resistance to an oppressive government. The confrontation with his disrupted country thus breathes new life into his research, which had been put on the back burner during his years of collaboration with Storefront for Art and Architecture, a New York cultural space dedicated to the arts since 1982. In a first phase, Neshat elects the woman’s body as a unique subject, so controversial and linked to the idea of shame, sin and sensuality in Islamic culture. The protagonists of the Women of Allah series are enigmatic figures. The artist, with the help of several photographers, investigates their faces, hands(Untitled, 1996), and feet(Allegiance with Wakefulness, 1994) and connotes them as “figures in power,” often shot in a frontal position, motionless but ready for action. The portraits, enveloped in a silent atmosphere, stand absolute like statues and reveal their ambiguous nature, all played out in the contrasts of black-and-white photography. In Speechless (1996), Neshat shows a woman’s face, framed halfway. The gaze is fixed and, along with the volley of a rifle, nails the viewer. The lips are clamped shut and, as the title suggests, the woman does not utter a word. Her face, however, is like the page of a book, speaking, in that it is covered entirely by writing. The artist chooses her original language, Farsi, or Persian, to communicate through the words of Iranian women writers, “engraved” on the skin of her protagonists. Another key element of the series is the presence of weapons, which further defines these women as warriors: defending their religion, their identity or perhaps their violated freedom. After all, Neshat’s artistic endeavors do not deviate from a strong civic commitment to democracy, feminism and against all forms of prejudice or censorship.

|

| Shirin Neshat, Untitled (1996; silver gelatin print with calligraphy, 170.2 x 121.9 cm) |

|

| Shirin Neshat, Allegiance with Wakefulness (1994; gelatin silver print with calligraphy, 118.7 x 134.62 cm; Denver, Denver Art Museum) |

|

| Shirin Neshat, Speechless (1996; photograph; Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum) |

|

| Shirin Neshat, Rebellious silence (1994; print and calligraphy; 142 x 98 cm) |

In the late 1990s the artist moved beyond, without abandoning, the photographic medium and with it the strictly political and social approach. He began to experiment with video and to place his figures in contexts that were less abstract, more immersive, and increasingly visually relatable to Iran, even when the works were made in Morocco, Mexico, or Tunisia. His debut to video is marked by The shadow under the web (1997). The work, set up on four screens, features Neshat herself. The artist, clad in the traditional chador, walks the streets of a city, from religious buildings to crowded markets. Her reflection here focuses on how culture denotes spaces (public, private, religious and natural) and how people, according to very specific social rules and limitations, can interact with them. Close in mode and in some respects also in theme is Soliloquy (1999). What is new is the explicit appearance of the West. Neshat, as in the first video work, approaches her soliloquy through the contrasting images of Middle Eastern and Western realities in relation to religion.

The artist thus moves within Islamic and Christian religious spaces, returning in both cases a negative feeling: on the one hand a fear of loss of individuality in Arab culture, on the other a feeling of separation from Christian society. Also at the turn of the century, the artist reaches the important milestone of the Golden Lion at the 48th Art Biennale in 1999: the video installations Turbulent (1998) and Rapture (1999) are awarded. The discourse shifts to an opposition between men and women in relation to culture. Turbulent argues the discourse between genders around two figures of singers. While the first, a man, performs a traditional song in front of an audience, the second, a woman, sings a melody without lyrics that echoes in an empty hall. Indeed, Iranian law does not allow women to perform in public. Thus, the same silence as in the Women of Allah series returns conceptually.

Neshat’s video work then flows into the more properly cinematic field in 2009 when she made her first feature film, which was also awarded the Silver Lion for Best Director in Venice at the 66th International Film Festival that year. Women without men (this is the title of the film) is based on the novel of the same name by Shahrnush Parsipur, an Iranian writer who was imprisoned for several years and is currently in forced exile in the United States. The story revolves around the affairs of four women and is set in 1950s Iran, during the upheavals that, with interference from the United States and Britain, led to the 1953 coup. There, Iranian Prime Minister Mossadeq was deposed in favor of Shah Reza Pahlavi. The narrative of the revolution, accurately cited in the film from historical photographs and followed through radio reports, is interwoven with the vicissitudes of the women, providing a very explicit denunciation of the repression of rights in Iran, the plight of women, the desire for change to return to a democratic and secular state, and the responsibilities of the West in the transformations the country has undergone in recent decades.

|

| Shirin Neshat, Soliloquy (1996; 16 mm film, 2 projections, color, sound, duration 15’; London, Tate Modern) |

|

|

| Shirin Neshat, Rapture (1999; video installation, two channels, 16 mm film, black and white, sound; Los Angeles, The Broad) |

|

| A frame from the film Women without men |

|

| A frame from Land of dreams |

Just as Iran is laid bare in Neshat’s work, the Western world is also plumbed for its contradictions in more recent works. Land of Dreams is one of the artist’s latest works. Already the sadly ironic title calls into question the myth of America as a land of openness and opportunity as opposed to the policies adopted by the Trump presidency against the human rights of vulnerable people and communities. Made starting in 2019, the project consists of a substantial series of photographs (over one hundred), two video installations, and a film to be released in 2021. Everything can be traced back to the figure of Simin, a young Iranian photographer who in the first work-video travels in New Mexico from house to house with the desire to collect and census the dreams and nightmares of a population varied in ethnicity. The portraits, always in black and white, a stylistic signature that at this point can undoubtedly be assigned to Neshat, also bear the Farsi transcription of each subject’s name and dreams. The artist with this complex work not only brings together all the artistic media she has experimented with but also pushes her social and cultural investigation in the direction of a parallelism between the United States and Iran, even in light of the new tensions between the countries in recent years.

After portraying Iranian women during the 1990s, the artist now captures the faces of America. In this way, her work transcends the issue of feminism and Iranian politics in the narrow sense and, from photography to film, amplifies her message on a global scale for an art that is not entertainment but an uncomfortable and powerful voice of resistance and an exercise in social responsibility.

The author of this article: Stella Cattaneo

Specializzanda in Storia dell'arte e valorizzazione del patrimonio artistico presso la Scuola di Specializzazione dell'Università degli studi di Genova. Attualmente curatrice di Casa Museo Jorn (Albissola Marina, Savona), ha partecipato a convegni e giornate di studio all'Università di Losanna e all'Università di Genova (2019) e a seminari internazionali di museologia (école du Louvre, 2018). I suoi interessi di ricerca si rivolgono prevalentemente all'arte contemporanea con particolare attenzione al periodo del secondo dopoguerra e all'opera di Yves Klein.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.