Admired for centuries and called “the most beautiful room in the world” as early as 1475 (i.e., just one year after the decoration work was completed), the Bridal Chamber still attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors to Mantua every year. A symbolic work of the Italian Renaissance, the Camera Picta (as it is called in ancient documents) is undoubtedly one of the greatest masterpieces of Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506).

The artist, born in Padua and a citizen of the Republic of Venice, was insistently invited to Mantua by the city’s lord Ludovico Gonzaga, beginning in 1458. The invitation was finally accepted only in the early 1460s, when the painter settled in the city with his entire family. From that moment on, Mantegna, already an artist of acclaimed fame, linked his name indissolubly to that of Mantua, to such an extent that Giorgio Vasari went so far as to erroneously call him “pittor mantoano” in his Lives.

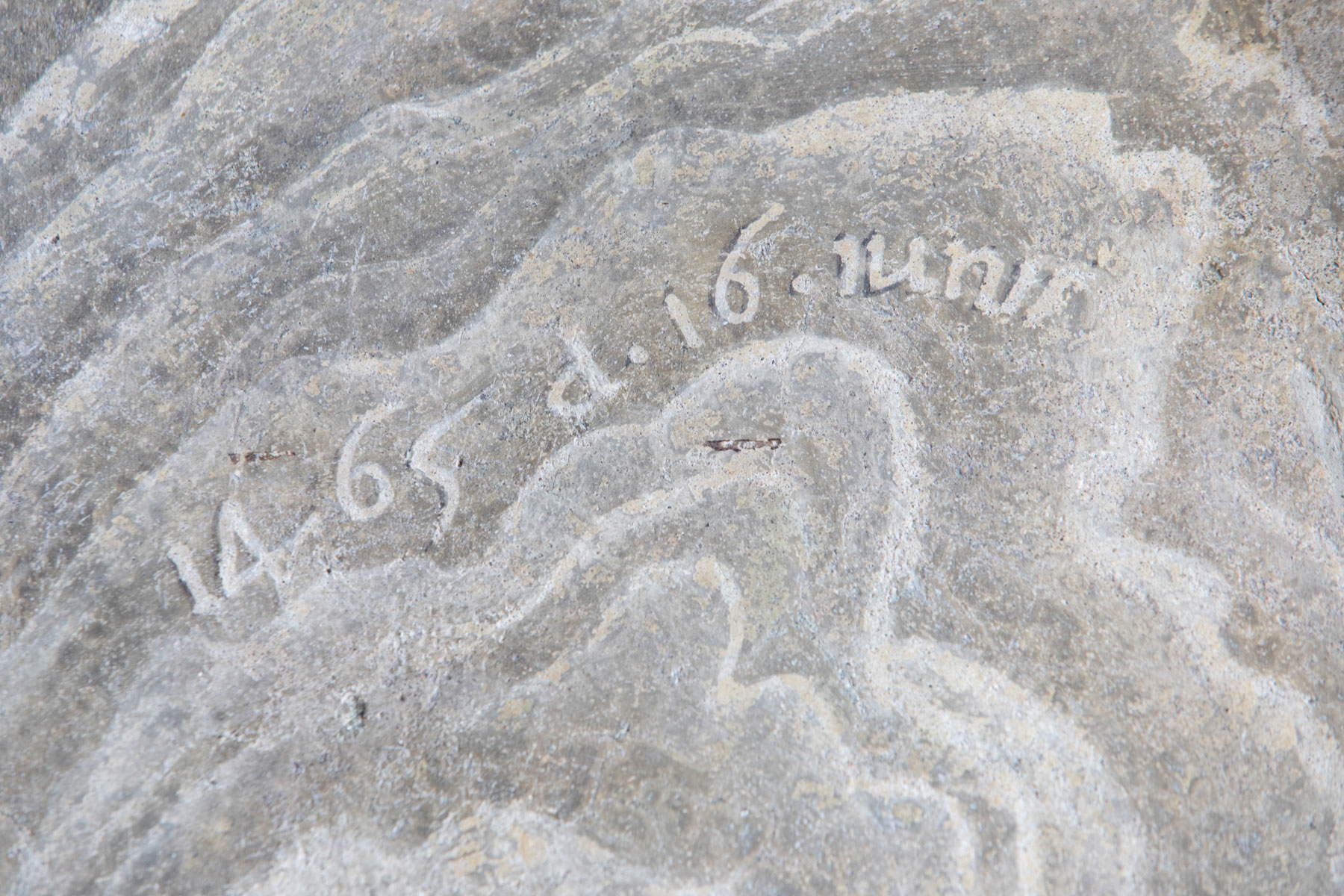

Andrea Mantegna was in the service of the Gonzaga court for over four decades, working for three different generations of the household. Nine of these years were spent painting the walls of the Camera Picta. The temporal coordinates of this long pictorial worksite are recorded in writing inside the chamber itself: the plaque supported by winged cherubs above the entrance door shows the date of the end of the work, 1474, inserted within the dedicatory inscription. The start date, however, is hidden, painted as a faux graffito in the faux marble decorating the splay of one of the window wells. It reads “1465 di 16 junii,” or June 16, 1465.

The entire pictorial decoration of the Chamber tends to redefine (and at the same time embellish) the actual architectural space. The faux bas-reliefs that adorn the vault, on faux gold mosaic backgrounds, are so admirably executed that they can often be mistaken for actually three-dimensional works. The walls of the room are painted in such a way as to look like the arches of a pavilion supported on pillars, and oftentimes the boundary between physical space and the frescoed scene becomes extremely blurred: some of the dogs, for example, rest their paws on the fresco frame, as if crossing the boundary between reality and artistic fiction.

Between the pillars that pretend to support the vault is painted a metal bar, from which hang precious curtains worked in geometric weaves of Moorish inspiration or in griccia motifs, a decorative element particularly in vogue in the most refined courts of the Renaissance. The draperies appear closed on two of the four walls. On the others, however, they appear open, detached, or even wrapped around the pillars of the pavilion in order to show the viewer what is happening beyond them.

|

| Andrea Mantegna, frescoes of the Bridal Chamber (1465-1474; Mantua, Castello di San Giorgio), view of the room. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, frescoes of the Bridal Chamber (1465-1474; Mantua, Castello di San Giorgio), view of the ceiling. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| North wall of the Bridal Chamber, Court scene. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| West wall of the Bridal Chamber, scene of the Encounter. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| The famous oculus of the Bridal Chamber. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| The paintings simulating reliefs. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

A large collective portrait of the Gonzaga court appears on the fireplace wall, known as the “Court Scene.” The commissioner of the work, Ludovico Gonzaga, second marquis of Mantua, is portrayed here surrounded by sons and daughters, courtiers and advisers. Prominent among the figures flanking him is his wife Barbara Hohenzollern of Brandenburg, of noble German lineage, who came to Mantua in marriage in 1433, when she was only 10 years old. The members of the marquis couple are the only figures portrayed seated. All others are standing, as a sign of respect. Valuable oriental carpets are depicted under the feet of the Gonzagas. This is an exceedingly interesting, and often unnoticed, iconographic element that tells of the refinement and luxury of the court. Carpets similar to these are found in other works by Mantegna, for example in the Martyrdom of St. Christopher in the Ovetari Chapel of the Church of the Eremitani in Padua and in the majestic San Zeno Altarpiece in Verona.

Also depicted among the characters surrounding the marquis and his wife are two prominent personalities, key figures in the climate of cultural and artistic renewal that saw the Gonzagas among the main protagonists. In the aged figure, wearing a black cap and looking sadly downward, portrayed immediately behind Ludovico (and partially hidden by him), it is usual to recognize the figure of Vittorino da Feltre (Feltre, c. 1378 - Mantua, 1446), who in Mantua itself had founded the Ca’ Zoiosa, the school at which some of the most celebrated figures of the Renaissance were trained. These included, in addition to Ludovico Gonzaga and Barbara of Brandenburg themselves, Federico da Montefeltro (future duke of Urbino) and Gregorio Correr (future abbot of San Zeno and commissioner of the famous Mantuan altarpiece). Although Vittorino had already been dead for almost twenty years by the time work began on the Camera Picta, it is plausible to think that the marquis of Mantua strongly wanted him portrayed at his side, to signify with anachronistic homage his gratitude to the master for the teachings he had received. After all, Federico da Montefeltro also wanted an effigy of Vittorino to be placed inside his famous Studiolo in the Ducal Palace in Urbino. On the same wall appears the portrait of another illustrious personage of the time: behind Barbara, dressed in black, is Leon Battista Alberti. Numerous were the relationships between the lords of Mantua and the architect: as early as the mid-1530s Alberti dedicated the Latin version of De Pictura to Ludovico’s father Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, and Ludovico himself entrusted him with the important projects of the Tribuna della Santissima Annunziata in Florence and the churches of San Sebastiano and Sant’Andrea in Mantua.

If the richness of the robes, textiles and furnishings is entrusted with the task of narrating the refinement and sophistication of the Mantuan court, the presence of Leon Battista Alberti and Vittorino da Feltre is entrusted with an equally important task: By showing within his own entourage, among his family members, courtiers and familiars, even these prominent personalities, Gonzaga intended to present himself as the lord of a cultured and erudite court, inclined to stand as protector and promoter of the arts.

Among the various characters portrayed in the court scene, the figure of a dwarf also appears. The presence of dwarves at the Gonzaga court is widely attested in historical documents, and there are numerous effigies of them in Gonzaga circles. In the Ducal Palace of Mantua itself there are other images of dwarves: in the fresco depicting the Oath of Luigi Gonzaga in the Chamber of the Captains in the Great Apartment of the Castle and in Pisanello’s frescoes in Corte Vecchia. And again, a dwarf in armor appears on the medal cast by Pisanello himself for Gianfrancesco Gonzaga. The dwarves were entrusted with the task of entertaining family members and their guests. And it is perhaps for this reason that the dwarf effigy in the scene (perhaps the one named Lucia, remembered in some documents) is the only character looking out of the scene, directly in the direction of the viewer.

Another significant presence is that of the dog crouching under Ludovico’s pew. Six other dogs appear in the room, on the other frescoed wall: a pair of molossoids, a greyhound, two hounds and a spinon. But the dog portrayed on the Court wall seems to be reserved a privileged role. It is in all likelihood Ruby, the marquis’ favorite bracco, mentioned in a numerous series of archival documents. At the same time, however, the dog is also to be understood as a symbolic element, with reference to the theme of fidelity. With this same meaning, in fact, the image of a dog appears on the reverse side of a medal made for Ludovico by Bartolomeo Melioli (Mantua, 1448 - 1514) in 1475, in which the lord of Mantua appears seated on a scanno, under which the trusty animal sits. In front of them are Minerva and the personification of Faith, and the scene is accompanied by the inscription “Faith and Pallas assist the faithful and wise Prince.”

|

| LIncounter between Ludovico (left) and Francesco Gonzaga (right). Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| Court Scene, collective portrait of the Gonzaga court. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| Putti holding the tabula dedicatoria. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

Marquis Ludovico, lord of the court and commissioner of the work, is the only character depicted twice within the Camera Picta. In fact, he also appears on the wall known as the “Meeting Scene,” where he is portrayed together with other characters. Among these, in addition to the illustrious presences of Emperor Frederick III of Hapsburg and King Christian I of Denmark, stands out the marquis’ second son, Francesco Gonzaga, the first member of the household to have donned the cardinal’s purple, that is, the first Gonzaga to have embarked on the path to an ecclesiastical career, which, most likely, the Gonzagas hoped would end with an election as pope. Which, in reality, never happened. To give shape to this dream of the household, however, Mantegna painted in the background of the scene a view of Rome, seat of the Papacy. Some famous Roman buildings can be recognized there: the Pyramid Cestia, the tour of the Aurelian Walls, the Colosseum and Castel Sant’Angelo.

Still of Rome, but this time of ancient Rome, it also tells of the decoration of the vault. Here, in fact, the first eight Caesars appear, portrayed in clypeus supported by winged putti, painted in grisaille. In the center of the ceiling is the famous oculus open to the sky, from which some figures, perhaps the servants of the court, look out to see what is happening inside the chamber. Along with them is a peacock, a symbol of glory and beauty, but also of immortality. And again, from the balustrade of the oculus, putti with multicolored wings appear in bold and perfect perspective. Identical in shape and size to those depicted in grisaille under the Caesars, but this time in color, as if these were figures brought back to life by the spirit of the Renaissance. A rebirth very similar to this had already been staged by Mantegna in the San Zeno Altarpiece in Verona: here, too, the angels surrounding the throne of the Virgin closely resemble those sculpted to decorate the architecture containing the sacred conversation. But if in the Veronese work Mantegna, in bringing the ancient heroes back to life, dressed them in colorful garments and fitted them with aureoles, to make them angels, in Mantua no addition was necessary. To color alone was delegated the task of bringing the ancient back to life.

Other winged putti, even with beautiful butterfly wings, finally appear above the entrance door to the Camera, depicted in the act of holding up the tabula dedicatoria in which, in Latin, it is recorded how Andrea Mantegna had painted this work for Ludovico Gonzaga and his wife Barbara, “incomparable glory of women.” In the inscription, Mantegna calls his own work an “opus tenue.” The literary reference is to the concept of tenuitas, or the subtlety used in rendering the most minute details, made famous in the famous anecdote told by Pliny about Apelles and Protogenes. And it is precisely the minutest details of the Camera that made it famous as one of the most supreme masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance.

And it is precisely among the many details of the chamber that Mantegna’s self-portrait is also hidden: concealed in the candelabra decoration of one of the pillars, in fact, appears the face of the painter, who evidently could not resist the temptation to portray even himself inside that masterpiece that took nine years of painstaking work to complete.

|

| The griccia decorations of the faux curtains. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| Lyscription bearing the date work began: June 16, 1465. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| The carpet in the Court Scene. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| One of the molossoids. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| Probably Rubino, Marquis Ludovico’s favorite bracco. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| Spiny dog. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| The view of Rome. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

|

| Mantegna’s self-portrait. Ph. Credit Alessandro Pasquali - Danae Project |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.