London, Oct. 3, 2018: the Vercelli Book returns to its homeland after more than a thousand years, to be displayed at the exhibition Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Art, Word, War. For the first time, the manuscript is presented at the British Library in a display case with the other three surviving volumes containing Old English poetic texts: the Codex Exoniensis from the Cathedral Chapter Library in Exeter, the Cotton Vitellius from the British Library in London, and the Junius XI from the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Codex CXVII of the Vercelli Chapter Library, known since the 19th century as the Vercelli Book, is the only one to be preserved outside the United Kingdom.

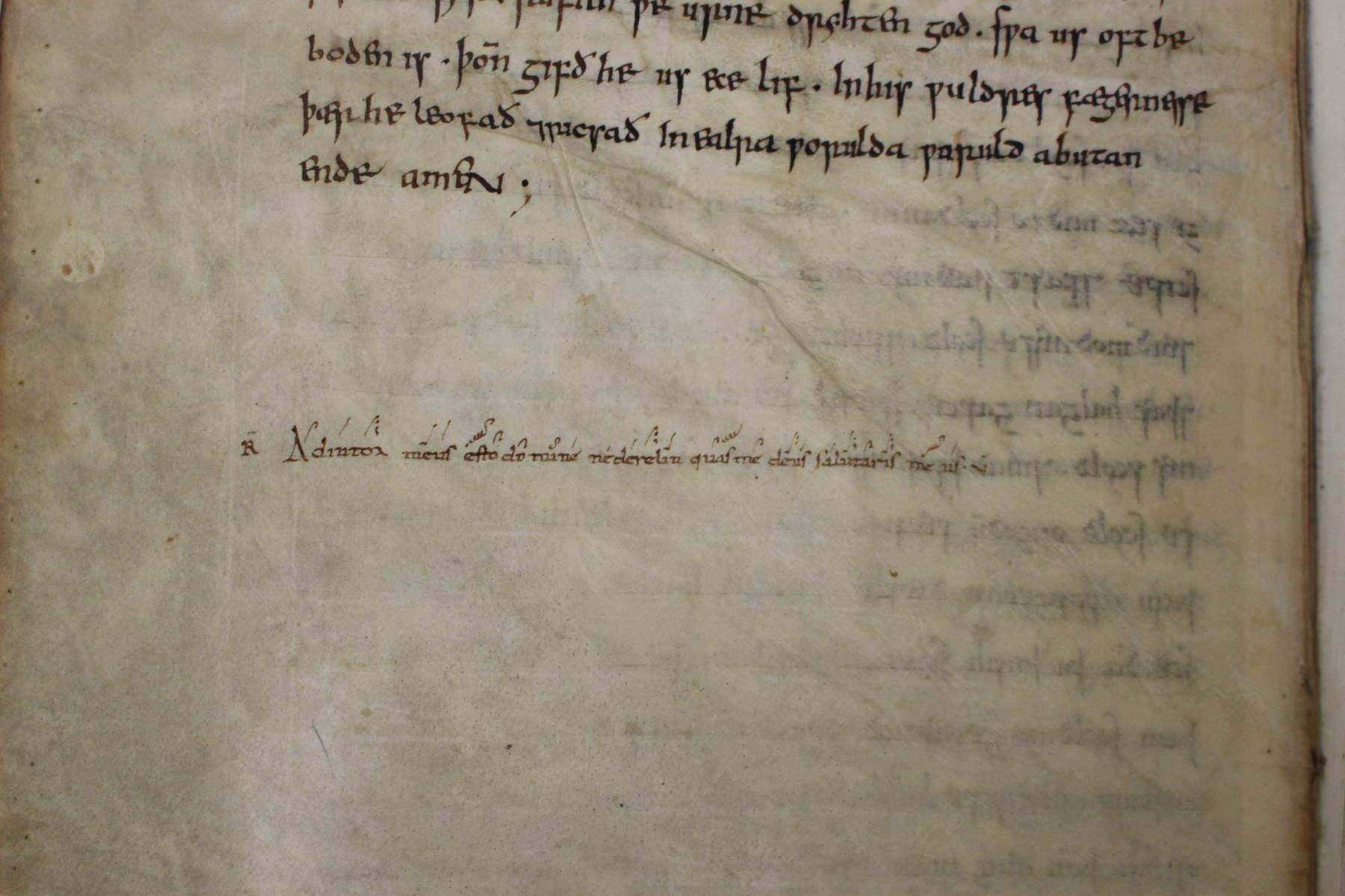

We are not aware of either who the first possessor of the Vercelli Book was or when it arrived in Vercelli, however the Latin responsory with neumes, written in a northern Italian hand of the late 11th century, documents that the book was in this area before 1100. This source allows us to speculate that it left England at the turn of theyear 1000, a few decades after it was packaged in a Kent scriptorium.

The volume was mentioned explicitly for the first time in an inventory of the Vercelli Cathedral Chapter, compiled in 1602 by Canon Giovanni Francesco Leone as Liber Gothicus, sive Longobardus, followed by the note eo legere non valeo. No mention in the inventories of 1361 and 1426, perhaps because as the centuries passed no one was able to understand the language in which it was written, very different from the medieval Latin common on the continent.

In 1748 the Veronese Giuseppe Bianchini, a world-renowned paleographer, cited it as Liber ignotae linguae. It remained undeciphered until the late eighteenth century, when Luigi Lanzi first identified the language, citing it as a book in letter incognita Anglosannica or Longobardica that is.

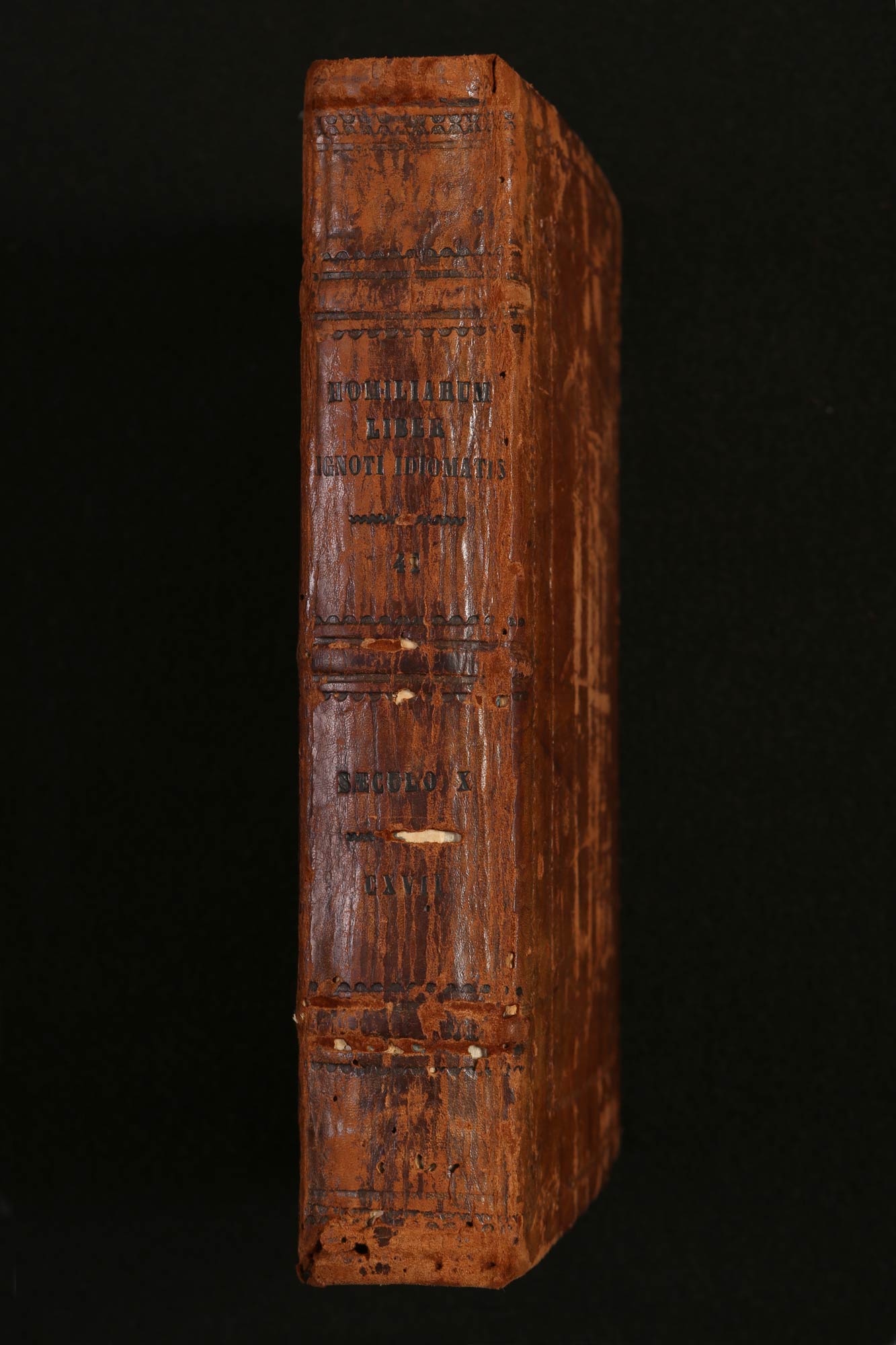

By the next century the manuscript was brought to the attention of the world scientific community thanks to German jurist Friedrich Blume, who transcribed part of the text in 1822 during his visit to the Library. Later, in 1834, the young German scholar C. Maier was commissioned to complete the description and transcription of the text (now preserved at Lincoln’s Inn Library in London, Misc. 225). From that time the Vercelli Book became famous, so much so that it was mentioned in 1842 in the guide For travelers in Northern Italy (London: John Murray and Son), among the treasures of the Chapter Library: Amongst the other manuscripts are Anglo-Saxon poems, including one in honor of St. Andrew, and very possibly brought from England by Cardinal Guala. And still today, the spine of the book binding reads Homiliarum liber ignoti idiomatis.

|

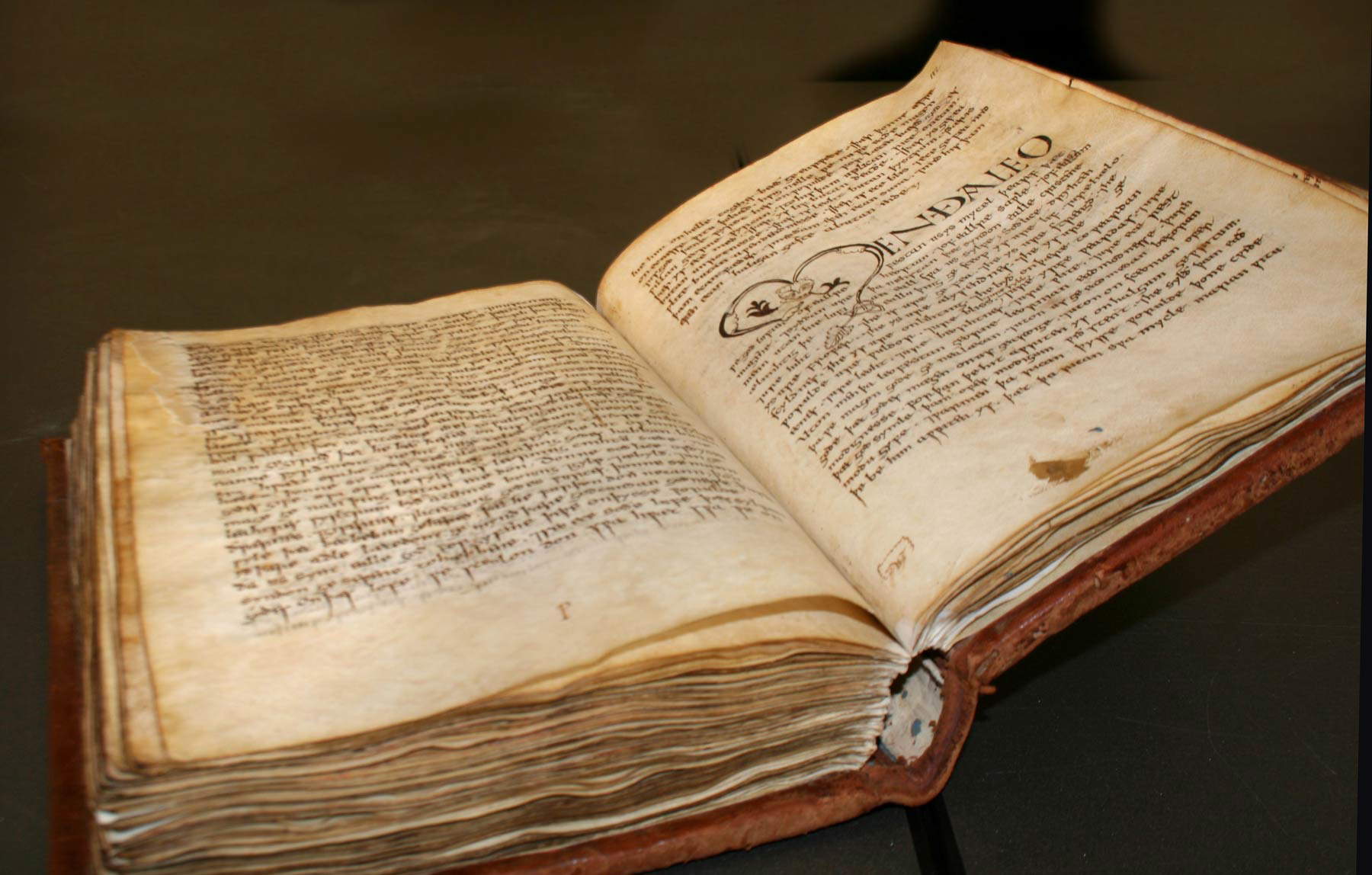

| Vercelli Book (Second half of the 10th century; parchment and leather binding on 18th-century wooden boards, 325 x 220 mm, southeastern England; Vercelli, Metropolitan Chapter of the Cathedral of SantEusebio Vercelli, Chapter Library, ms CXVII) |

|

| The repository in which the manuscripts, including the Vercelli Book, are stored. |

|

| Spine of the eighteenth-century binding of the Vercelli Book with the inscription Homiliarum liber ignoti idiomatis |

|

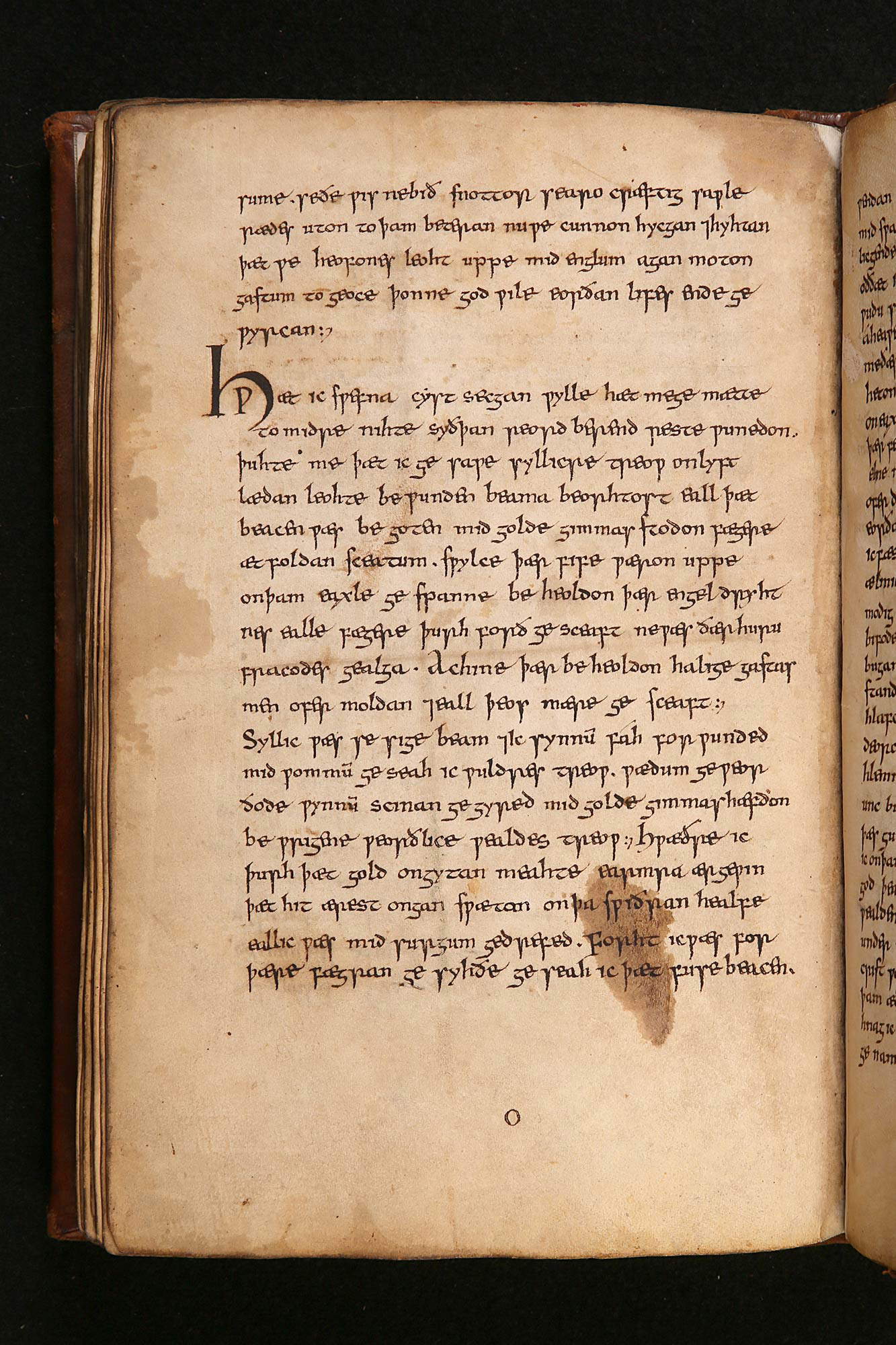

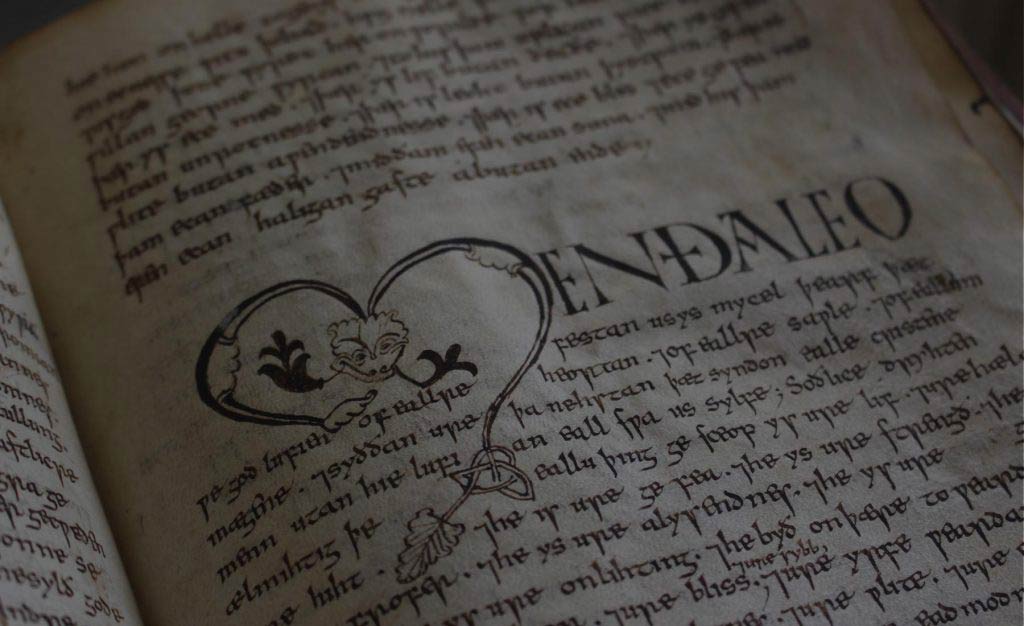

| Incipit of the poem The Dream of the Rood, folio 104v. Open page for the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms exhibition at the British Library in London. |

The mystery of his arrival in Vercelli continues to be a dilemma that will probably never be solved. In fact, nineteenth-century theories have been largely superseded, although there are still scholars who persevere in linking the book to the Vercelli cardinal Guala Bicchieri (1150 - 1227), papal legate to England for several years, as the person responsible for the arrival of the manuscript and other assets now held among the holdings of the Cathedral Chapter. Or even to speculate that the volume was abandoned in Vercelli by a pilgrim traveling on the Via Francigena, who died in the Hospital of Santa Brigida where hospitality was provided to travelers from the United Kingdom.

Vercelli’s role as a stopover on the route from Canterbury to Rome is undoubtedly important, and the hypothesis that a high-ranking traveler, a bishop or cardinal from the north, donated the manuscript to a prelate from Vercelli is among the plausible ones. Perhaps the Cardinal of Canterbury Sigeric himself, who mentioned Vercelli as stop XLIII in his travelogue of 990.

One of the most credible theories links the Vercelli Book to Leo, bishop of the city from 998 to 1026: a leading figure in European politics and written and artistic culture, an adviser to the German emperors, a connoisseur of Old Saxon (a language very similar to Old English) scholar and bibliophile who donated several manuscripts to the Capitular Library of Vercelli, including one of his poetic compositions known as Metrum Leonis. The Vercelli bishop is also associated with the commissioning of the monumental crucifix in gold and silver foil, which still stands in the center of the cathedral transept.

Among the most striking texts handed down from the Vercelli Book is, in fact, the poem The Dream of the Rood, considered by some to be the most enigmatic poem in Old English and which has come down to us thanks to the Vercelli Book. In a dreamlike vision, the Cross tells the story of the passion, speaking in the first person of the suffering endured with Christ. The text, dating back to the 8th century, conveys the image of a triumphant Christ, comparable to the one in the Vercelli Cathedral: the words take on descriptive power and are capable of conveying multiple meanings, enhancing the divine yet human dimension of Christ.

|

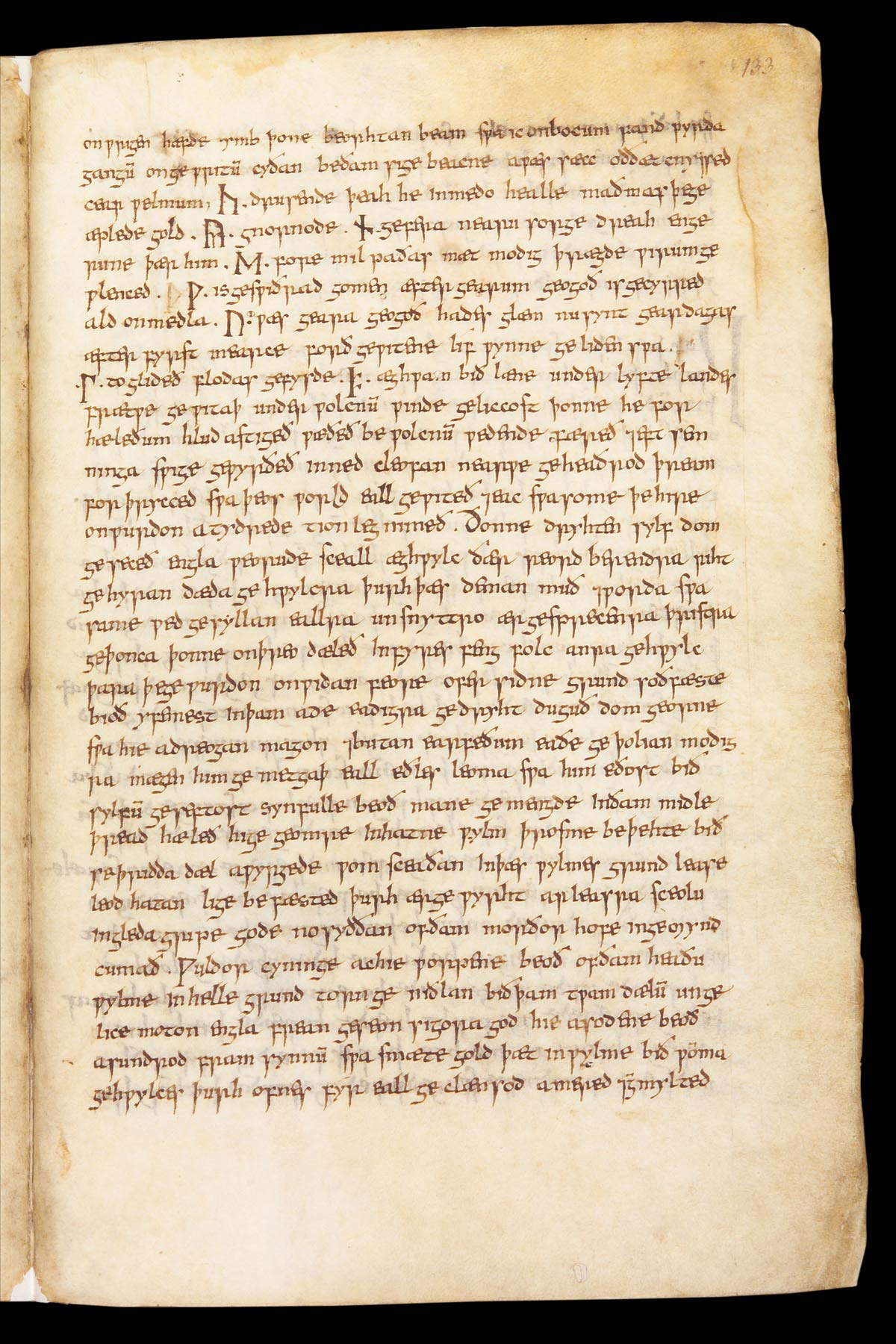

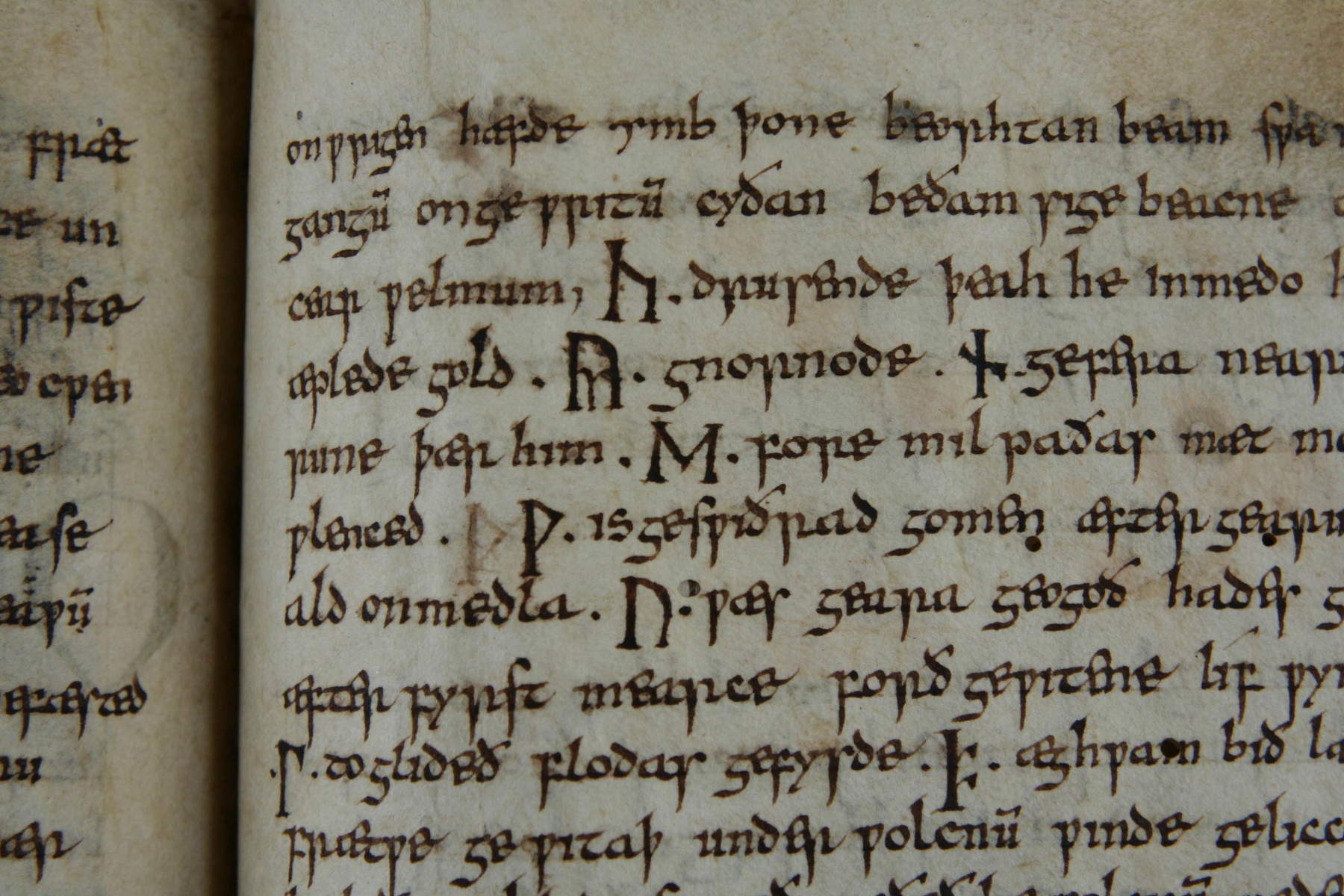

| Page with the eight runes forming the name of the poet Cynewulf, folio 133r |

|

| Detail of page with the eight runes forming the name of the poet Cynewulf, folio 133r |

|

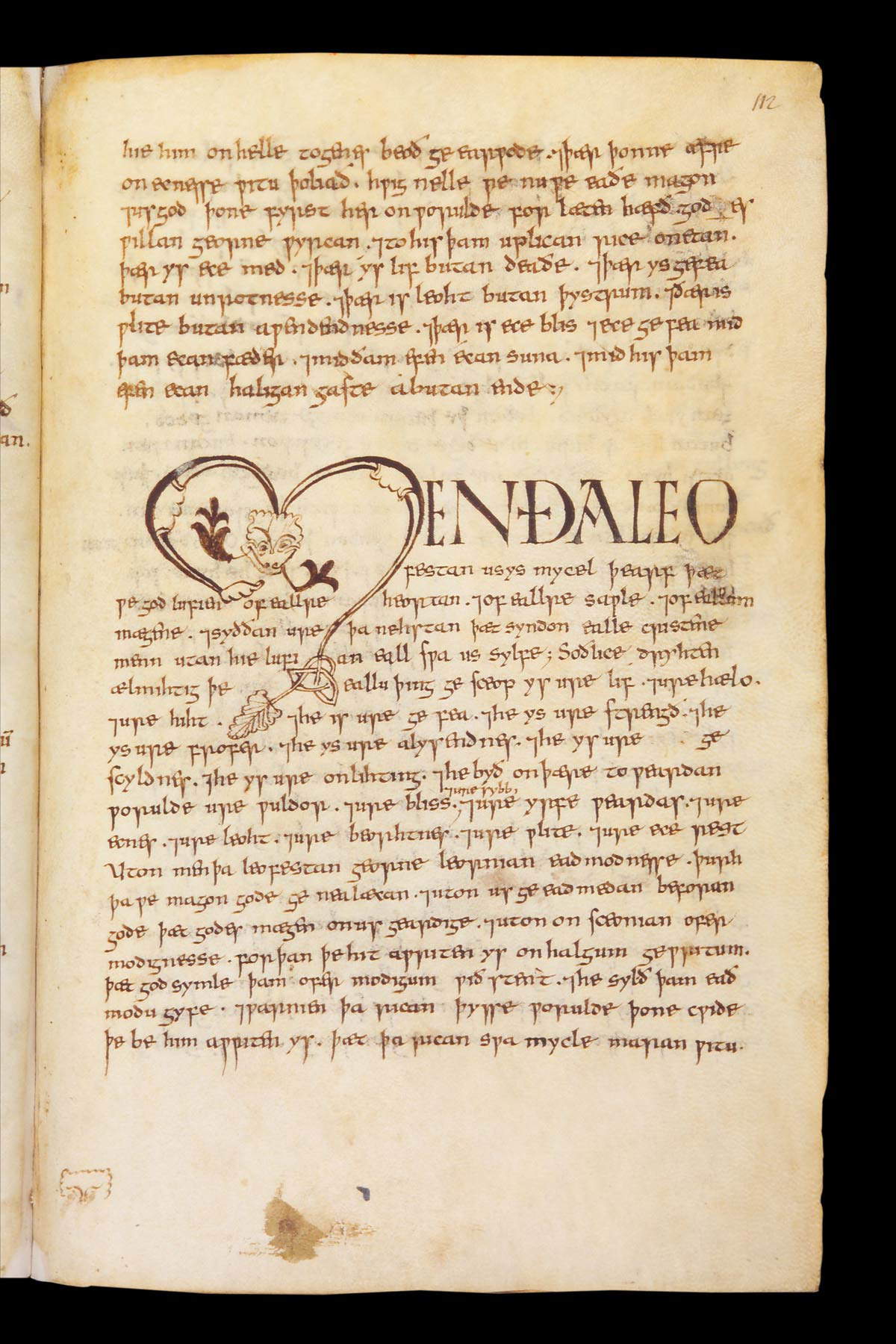

| Detail of the incipit of theOmeliadellelemosina with illuminated initial M, folio 112r |

|

| Incipit dellOmeliadellelemosina with illuminated initial M, folio 112r |

|

| Detail of the Latin responsory with neumes, written in a northern Italian hand of the late 11th century, folio 24v |

The Vercelli Book contains twenty-three prose homilies concerning important Church solemnities and six poetic compositions. It was written on parchment by a single copyist who copied it by drawing from non-patristic Latin sources and deutero-canonical writings, probably available in the library of his monastery, mostly in a mechanical manner, apparently without a logical order in the succession of texts. As many as eleven of the homilies are attested solely in the Vercelli Book making it, therefore, an invaluable linguistic and cultural document for the history of the Catholic Church in England before the Benedictine Reformation of the late 10th century.

Most of the poems are anonymous, with the exception of two poems The Fates of the Apostles and Helen, in which eight runic characters are used which, transformed into the Roman alphabet, correspond to the name Cynewulf, considered one of the most prominent figures in Old English Christian poetry, who probably lived in the 8th century. Runes have been used since ancient times as a method of prediction and for magical rituals, until the rise of Christianity restricted their use as a legacy of pagan rituals. Famous are the runes of the Ruthwell Cross, dated to the 8th century, in which passages from the Vercelli Book poem The Dream of the Rood are carved into its outline.

The physical characteristics of the book, its format, contents and almost total lack of annotations suggest that it had only one owner and that it was used as a devotional companion during one’s pilgrimage before being left in Vercelli. Indeed, the custom of donating manuscripts to churches is an ancient and well-known practice, as is the practice for clergymen to possess books useful for meditation and the exercise of their ministry even while traveling.

For more than a decade, the Chapter Library has been actively working with the relevant international scholarly community to deepen the study of the manuscript and attempt new research approaches aimed at delineating its material, historical, devotional and penitential context, also taking advantage of new non-invasive diagnostic investigation technologies.

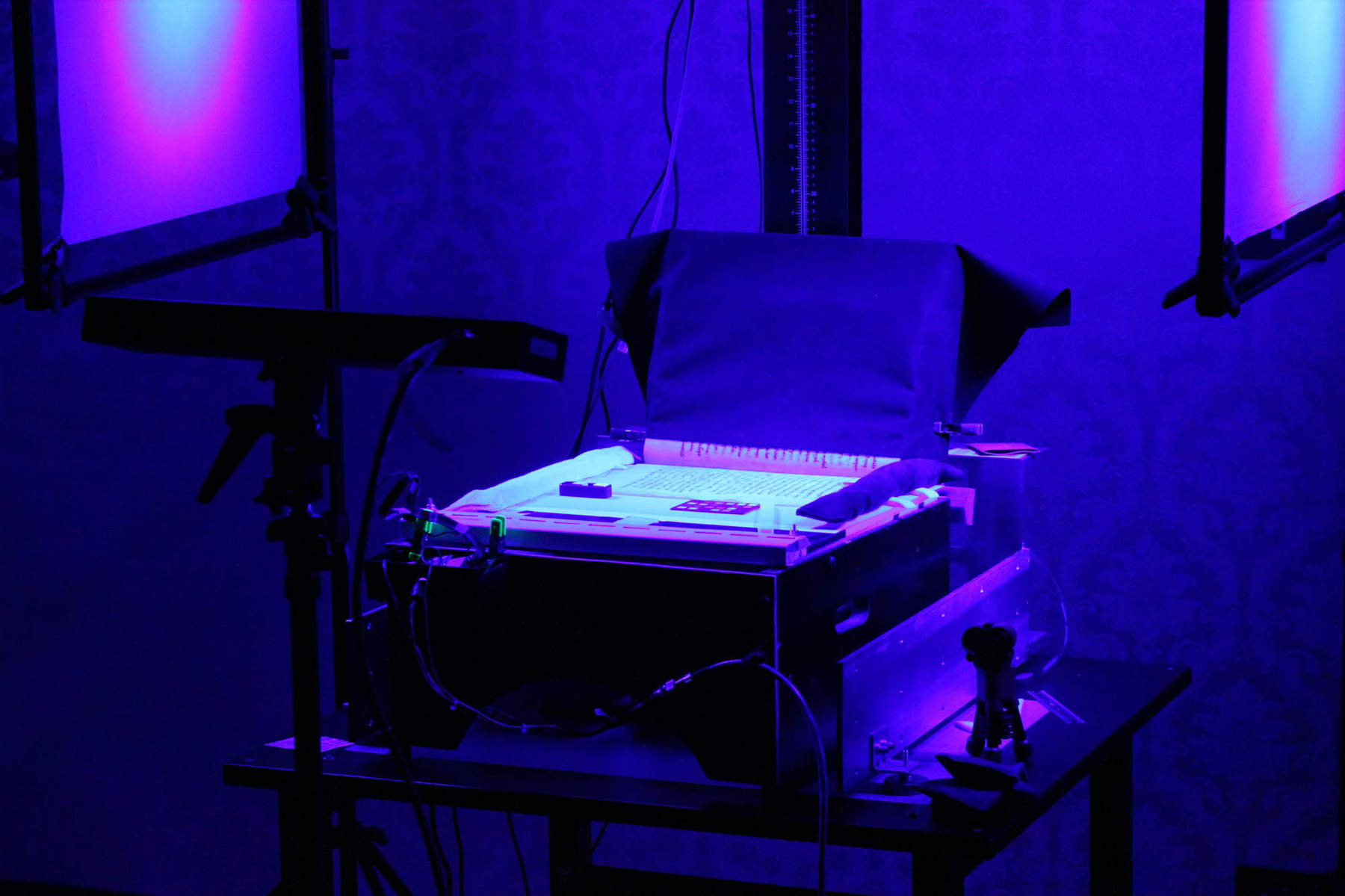

Since 2007, the Vercelli School of Medieval European Palaeography, established with Professor Winfried Rudolf, now a professor at the Georg-August Universität in Göttingen, has been active, aimed at studying and researching the manuscripts of the Chapter Library. In 2013 the Vercelli Book was subjected to multispectral survey by the Lazarus Project team of Rochester University (New York); in the same years XRF and Raman surveys began with the Interdisciplinary Center for the Study and Conservation of Cultural Heritage of theUniversity of Eastern Piedmont; in 2015 the Library joined the European project ECHOE - Electronic Corpus of Homilies in Old EnglishdellaGeorg-August Universität in Göttingen and University College of London.

|

| Multispectral analyses carried out in 2013 by the Lazarus Project, Vercelli Book page setup phase. |

|

| Multispectral analyses carried out in 2013 by the Lazarus Project, filming phase |

|

| Professor Winfried Rudolf with students from the Vercelli School of Medieval European Palaeography in 2019 |

|

| Character sketch C. Maier for the gaming Hwaet! The Vercelli Book Saga, drawing by Andrea Capone |

Vercelli, July 17, 2019: Hwaet! The Vercelli Book Saga, the gaming dedicated to the Vercelli Book and its journey, created with the CNR Institute for Educational Technologies in Palermo and the company Bepart of Milan. A new challenge that sees the entire scientific staff of the institution involved in an innovative, one-of-a-kind project, created in concert and with the advice of all the partners who have been working with the Library since 2007. A video game that will see the light of day in 2021 and will represent, without any doubt, a radical change that may lead to unexpected implications in the future: nothing new if one thinks of the many mysteries of the Vercelli Book!

The author of this article: Timoty Leonardi

Direttore della Fondazione Museo del Tesoro del Duomo e Archivio Capitolare di Vercelli.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.