Dominique Lora is curator of the exhibition Tina Modotti: The Genesis of a Modern Gaze (Aosta, Saint Bénin Center, Nov. 12, 2022 to March 12, 2023).

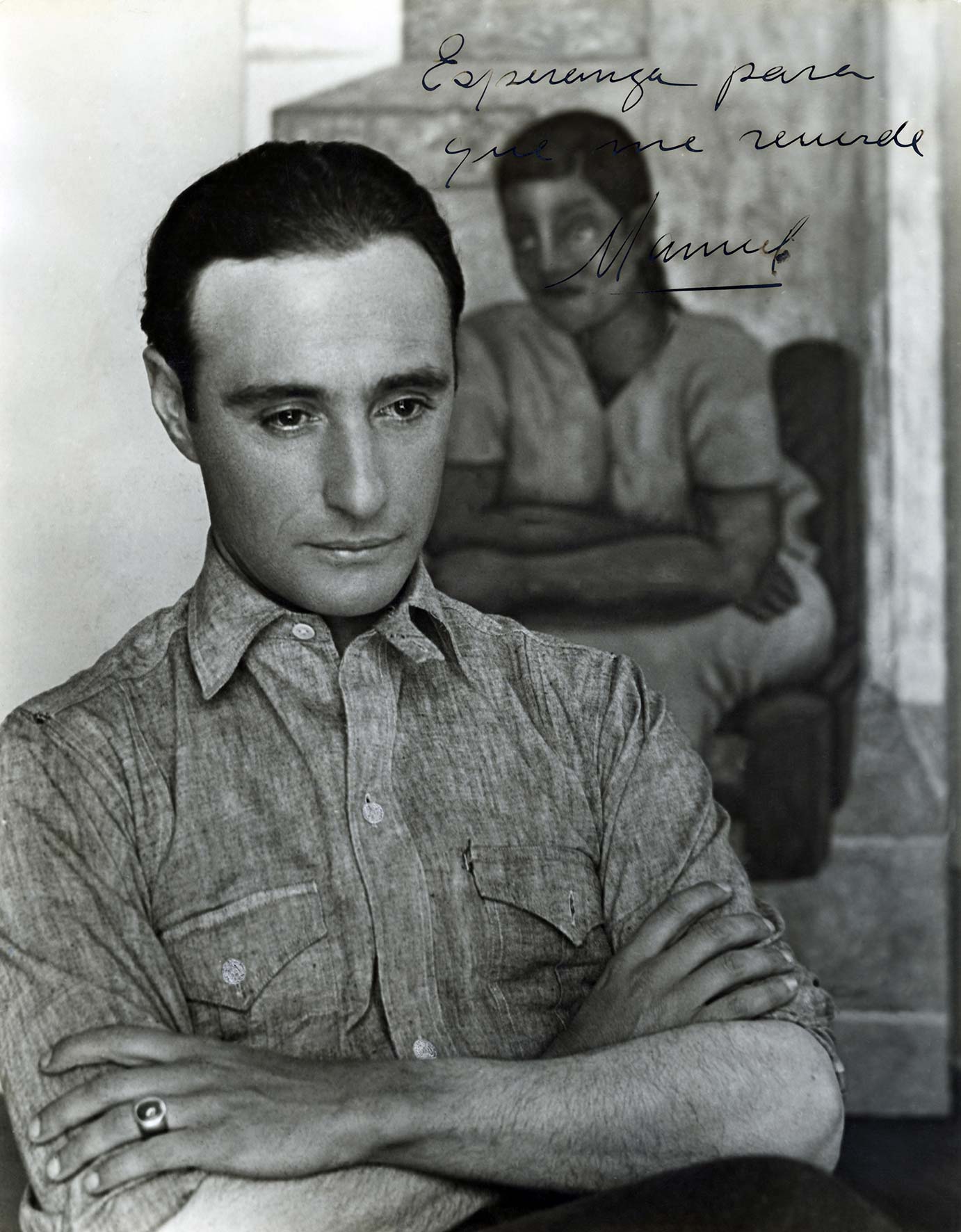

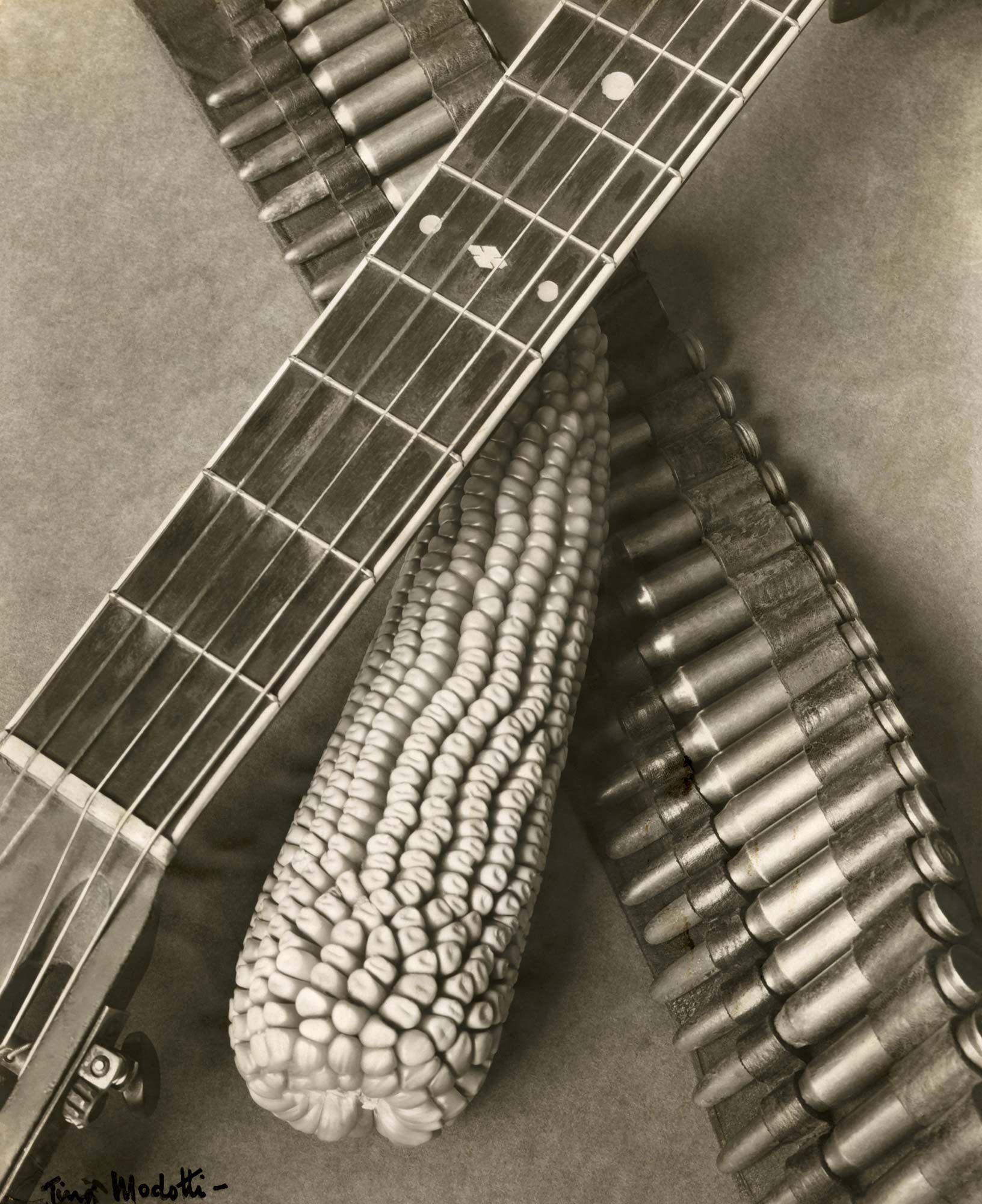

Adventurous, nomadic and magnificently mysterious, Tina Modotti ’s artistic personality is permeated by a rich and plural talent, but she is above all characterized by a sharp, lenticular gaze capable of reaching and penetrating the essence of individuals and things. A modern woman and artist ante tempore, Modotti has exerted a tangible, decisive and lasting influence on the development of photographic art in Mexico specifically (look at the work of Graciela Iturbide and Yolanda Andrade for example) and internationally in general. During the past two decades her work has attracted the attention of writers, filmmakers, artists, and curators. Yet the theme and subject matter of most of the in-depth studies and various publications devoted to her are generally focused on her romantic and political adventures or her relationships with other famous personalities of the art scene of the first half of the 20th century, including Edward Weston, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Dr. Atl, Nahui Olin or Guadalupe Marin.

The Italian photographer’s original work, reevaluated only since the 1970s by international critics, has been buried in the archives of various institutions, partly as a result of censorship enforced by the McCarthyist movement in America, beginning in the late 1940s. Today, his bold biography continues to influence, if not obscure, the perception of his unique and extraordinary work, placing a filter on the authentic and creative understanding of his work. And while his complex human adventure continues to inspire novels, comic books and documentaries, often based on the mystification or at least the novelty that was his existence, few until now have focused on his important artistic-cultural legacy and the fundamental influence his snapshots exerted on the formation of several generations of photographers. His freedom in representing the real and the sensual, rough and vivid, immediately distances himself from the abstract universe of his contemporary masters such as Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, Anselm Adams, Edward Steichen, Henri Lartigue or Eugène Atget. In fact, Modotti develops an instinctive and original form of humanity and understanding towards the world around her, which, in front of her lens, is revealed in its essence, devoid of any metaphorical virtuosity, even when representing a simple flower. Her works are candid and natural and can be interpreted as a modern version of the so-called sixteenth-century inculturative compositions: an oxymoronic expression that originated with and from Leonardo da Vinci and refers to the quick, spontaneous sketches that capture the immediacy of attitudes and movements of an open visual line that seeks the essence of form without entirely defining it.

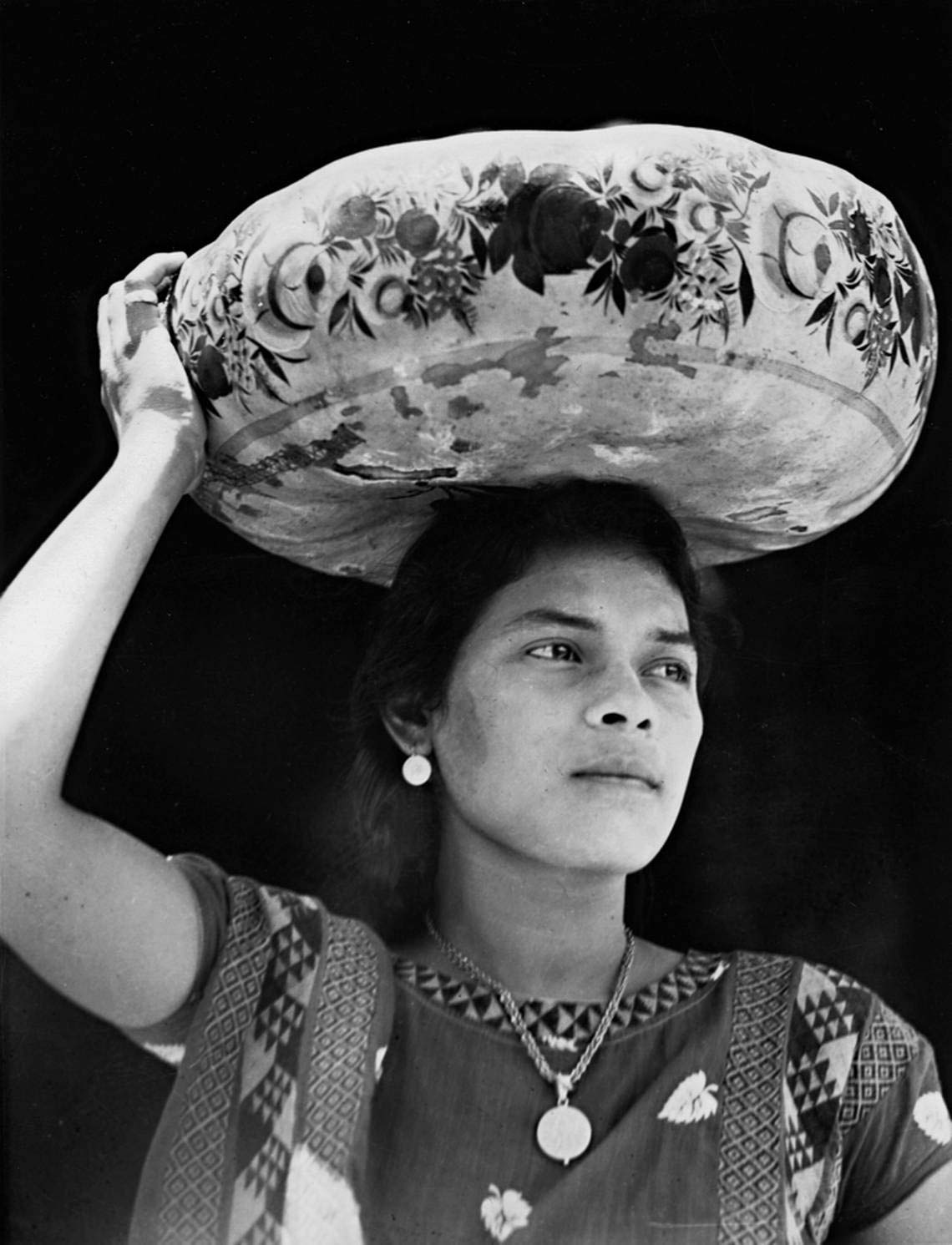

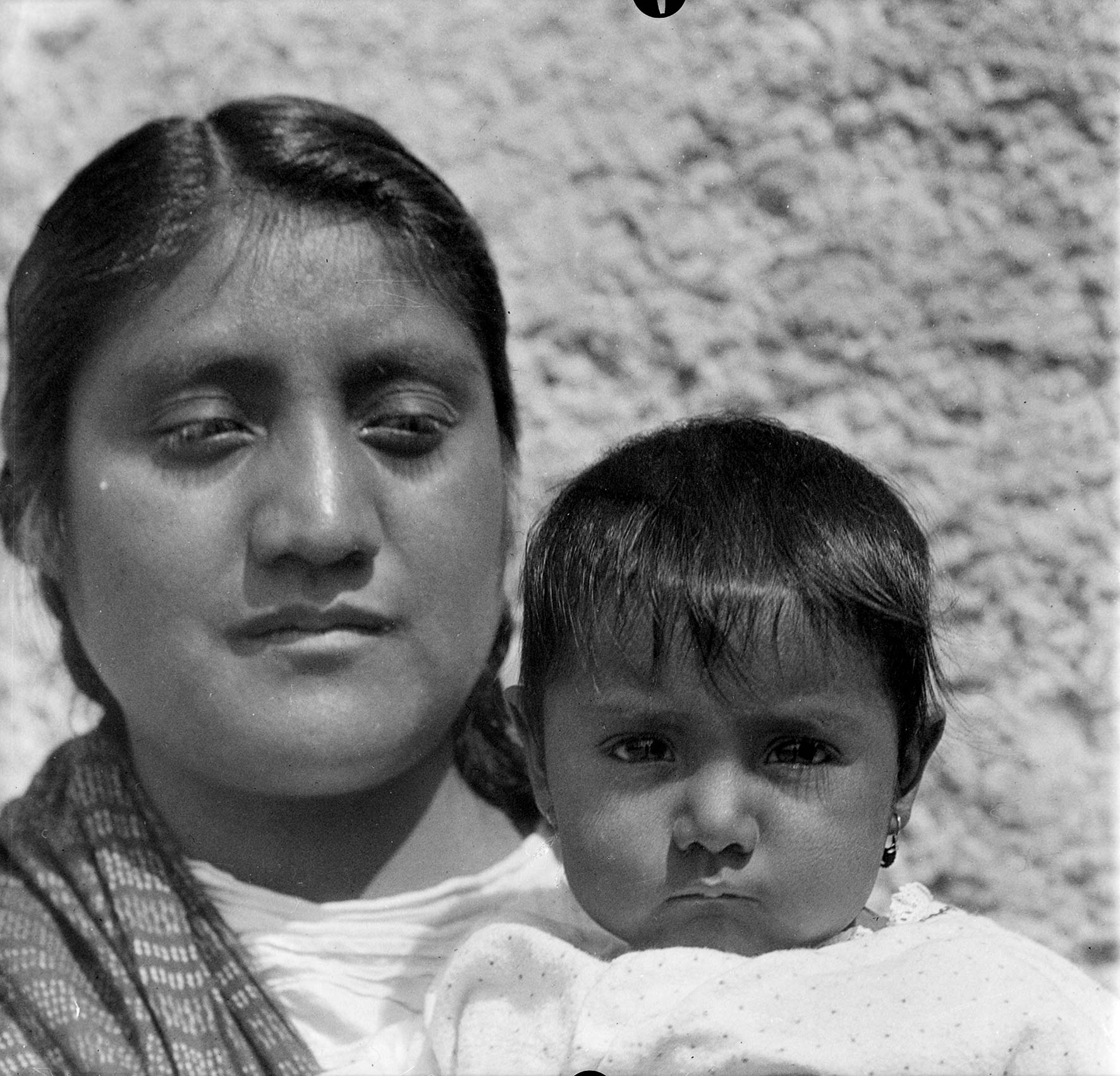

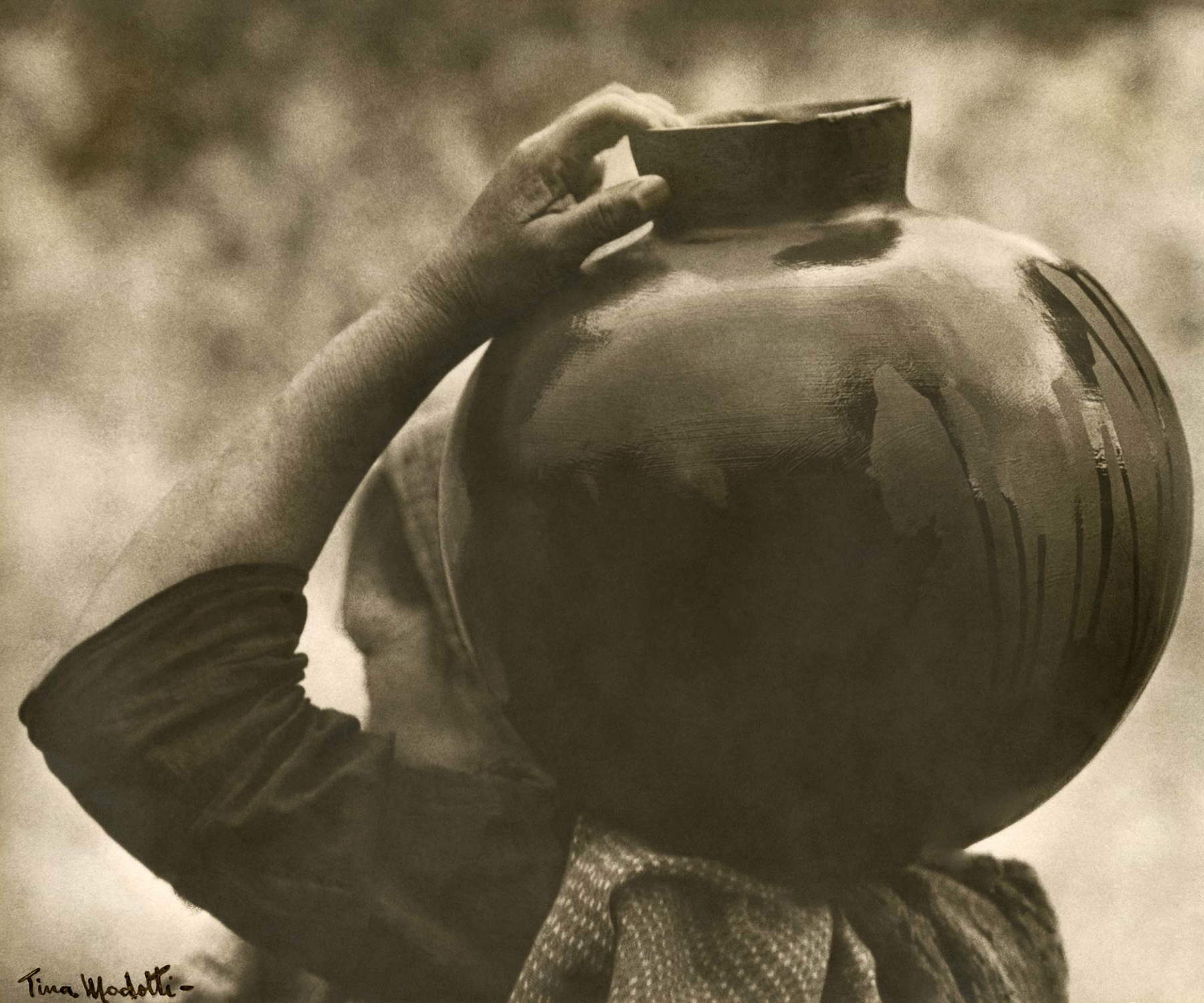

In the series of female portraits made in the Mexican countryside, the woman’s body is a universal vehicle and tool imbued with dignity and determination that transcends any monocultural viewpoint by eliminating any distinction between us and the “others,” between indigenous and foreign.

Here, wounds, fears, strengths and hopes are revealed, which combined show an unusual humanity made up of minorities whose uniqueness-but also universality-strongly stands against the illusion of a neutral and univocal majority. Each shot fervently depicts the authenticity that is reflected in the very act of photographing, lending an aura of sacredness to images that do not serve the purpose of entertaining, but rather that of documenting and telling, giving the artistic narrative an unprecedented autonomy. If the first works she produced (in the period of learning spent alongside Edward Weston, between the North American West Coast and her first trips to Mexico in the early 1920s) constitute glances and impressions of discovery and surprise through which the Udine artist portrays herself and the people close to her, she gradually goes on to develop a personal language that explores the truth of things and the effects of light on forms. This is a period of observation on the reality of individuals, cities and nature; a time marked by an uncertain technique but one that seeks definition in the warp of human experiences and emotions. To quote Roberta Scorranese: “In her early photographs Modotti pursued the desire to achieve a kind of formal reinterpretation of Weston’s teaching, such an effort aimed at transporting the observer to a specific place, a place, so to speak, less verbalized and closer to the subject of the image. But its heterogeneous or alternative forms of extreme simplicity govern the gaze of the beholder. And after looking with some attention, the viewer rearranges the physical limits of such universes in his own space, in a personal space, where objects begin, once again, to appear as universes. ”1

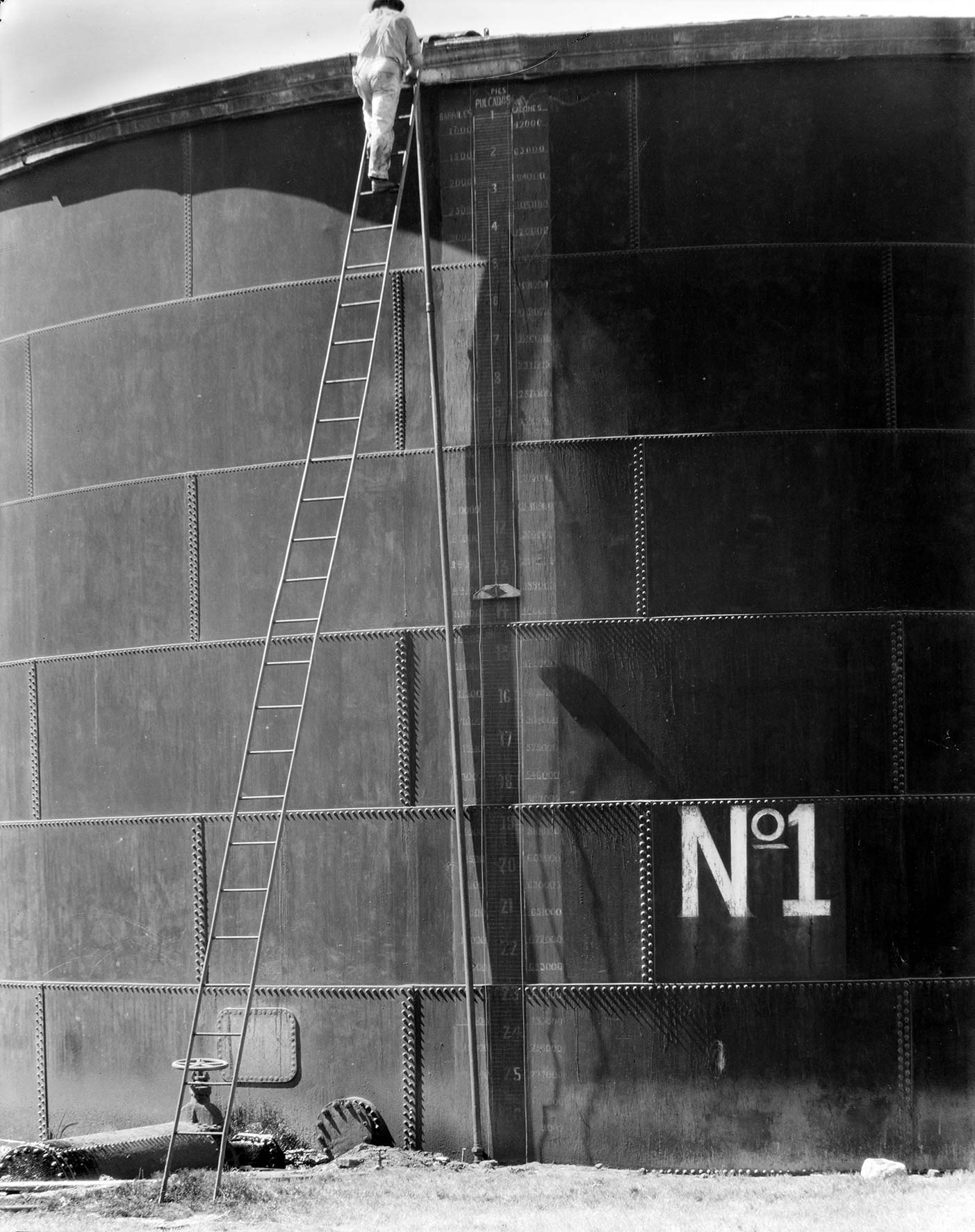

Tina’s work thus focuses on the visual narrative of a human and geographical reality characteristic of “her” Mexico. She undertakes a true travelogue in the city as well as in the countryside, capturing the conditions of those marginal groups that were emerging from the vicissitudes of the armed period of the revolution and recording the contrast between rural dwellings and city architecture, between ancient rural traditions and modern progress. In this context, Rosa Casanova points out how Modotti’s photographic production fits into the tradition of the so-called Mexican Costumbrismo2. A form of representation born in the mid-nineteenth century and aimed at representing the other and the elsewhere and rediscovering the world outside the central cores of Western civilization. In the early days, the dissemination of these images served the purpose of educating the middle classes about landscapes, peoples and customs considered important by governments and commercial establishments in the political and economic context of colonialism. Tina Modotti’s photographs transformed the parameters of Costumbrism and forged a modern type of representation; a crucial shift that revealed a unique way of objectively representing the animate and inanimate elements of reality. The visual tradition of Costumbrism could be considered the inspiration and origin of today’s intangible heritage conservation promoted by UNESCO. For example, the Udine-based photographer produced a series of shots dedicated to puppeteer Lou Bunin, immortalizing hands and puppets he handled that embody “those asymmetrical power relations between rulers and ruled, a subtle but powerful critique of social and political reality, Mexican. ”3

Depictions of urban, suburban and rural views, aimed at expressing human conditions, peoples’ traditions but also the history of progress, unite Modotti’s research with that of other great female photographers such as Lola Alvarez Bravo, Berenice Abbott, Consuelo Kunaga or, in Europe, Lucia Moholy-Nagy.

Exploring her deep sensibility, Tina experiments with forms and correspondences. For her, the work of art is a movement, a set of archives and living memories that, between past and future, make the invisible and forgotten everyday an emotional manifesto that expresses with courage and hope the unease, inconsistency and meaning of an often destitute present. Along with Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, Lee Miller Penrose, Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunnigham or Mexican female photographers such as Lola Alvarez Bravo4, Modotti stands out as a passionate and independent artist, avant-garde, courageous and above all an essential inspiration for generations to come. Like her peers, the artist traverses, during her artistic career, positions that are, so to speak, opposite, the result of having been both protagonist and behind-the-scenes character, model and photographer. Each of them specializes in her own way in experimenting with the nature of emotions through the representation of detail and fragments of reality. Their subjects explore the complexity of the self and investigate the meaning of an “other” humanity in an attempt to reestablish a spiritual as much as material connection between past, present and future. Modotti is a nomadic figure in search of a reality on a human scale who, looking through otherness and elsewhere, represents the hope for truth and freedom in a land yet to be discovered, a modern terra incognita. “The images document his expeditions through city neighborhoods; they are discoveries as much as insights: the urban in the country and the rural in the city.”5 His work constitutes an archive of memory that functions individually from individual to individual and generates a dialogue with the viewer in which the echo of the artistic gesture produces an unprecedented ability to perceive and understand the real. By revealing and reifying his own Lieux de Mémoire, the artist transposes his emotions into experiencing the immediate moment. Thus, vision and perception constitute a gateway to a broader understanding of the human condition.

Although Modotti reiterated several times during her career her desire to make a work devoid of any aesthetic construction - as if there were no space between the shot, understood as a gesture, and the object represented - her personality and soul stand between the lens and the subject despite herself. The artist does not escape the Zeitgeist, or the artistic spirit of his time, which sees international artists and masters composing works that are formally different but somehow embrace the same intent. Think, for example, of Eugène Atget’s photographic reportages, made between Paris and its suburbs in the years 1910-19156. Like Modotti in the Mexican countryside, Atget turned to the dispossessed people, and although he is on the whole considered an artist with a sophisticated style at the antipodes of Modotti, both portrayed at some point in their careers the housing and working conditions of the “rejected” or “forgotten” of the time.

In other words, no matter how different Tina’s artistic intentions are from those of other major artists of the time, it is impossible not to detect parallels and correspondences in terms of form and content. For example, think of the numerous close-ups of peasant women’s and washerwomen’s hands, which are reminiscent, at least formally, of Alfred Stieglitz’s experiments with O’Keeffe’s hands, executed between 1918 and 1920. However distant in intentions, the two photographers represent hands as an instrument of identity construction. For both are symbolic of timeless heroines; hands that weave, wash, work, protect, and build. "They are the hands of workers, expressing a political and human message that is immediately understandable. In a literal sense these hands do the work necessary for life in Mexico, but in a symbolic sense they represent the potential political power attributed to campesinos and trabajadores. "7 In other words, Modotti, like her contemporaries, portrays the female body to express the complexity of the real world.

Equally powerful is the series of Still-Lifes (still lifes) depicting flowers and plants, such as lilies or cacti, which closely resemble the coeval experiments of artists such as Imogen Cunningham; particularly the close-ups made by the latter in the 1920s and 1930s.

The depiction of certain flowers, such as lilies, calla lilies or cacti also recurs frequently in the artistic production of Georgia O’Keefe and Consuelo Kanaga. And as much as they have always fervently denied any erotic or metaphorical references or associations, it is difficult not to associate such representations with the cultural and social developments of the period (at least on an unconscious level) related to the liberalization of women in the world in general and in art in particular. Such botanical images are deeply intimate representations. “The images of calla lilies and geraniums, seem, at first glance unlikely candidates for a symbolic enterprise but precisely because they represent simple flowers with a domestic air, without any claim to exceptionality, they suggest their constant presence in the life of the author and in that of the Mexican people, acquiring an emotional charge that provokes a feeling of empathy in the viewer. The deeply chipped pot in which the geranium is planted, like the irregularity of the calla lily that begins to wither, communicate a feeling of suffering or at least project an idea of human suffering and transience. ”8 Finally, it should be noted that the experiments with flowers and plants echo a series of shots that the Luxembourgian photographer and painter Edward Steichen took between 1925 and 1928, and which (while stylized and technically highly crafted) prove how the Still-Life genre was universally perceived as a site of artistic experimentation beyond nationalities and genres9.

As Modotti reached artistic maturity, she shared with Gerda Taro, Margaret Bourke White, Lola Alvarez Bravo and Dorothea Lange, to name a few, a “documentary” attitude that took a passionate interest in the human, political and revolutionary upheavals that characterized nations such as the United States, Mexico, the Soviet Union and Spain during the first half of the twentieth century. Their photographic diaries of war and social or racial change still constitute essential evidence for understanding such historical contexts. In 1929 Tina published, in Mexican Folkways magazine, a personal reflection on the relationship between the photographic medium and political engagement. She writes, “There has been much discussion in recent years as to whether or not photography can be a work of art comparable to other plastic creations. Of course, opinions vary between those who accept photography as an expressive medium equal to any other, and those - the short-sighted - who continue to see this twentieth century with the eyes of the eighteenth century and are therefore unable to accept the manifestations of our mechanical civilization. But, we who use the camera as an instrument, as the painter uses his brush, are not interested in contrary opinions; we have the approval of those people who recognize the role of photography in its many functions and accept it as the most eloquent and direct means of fixing or recording the present age. ”10

For Riccardo Toffoletti, this expression of Modotti’s represents the first document onengaged photography in history, arguing that, if in the last postwar period, photographers, filmmakers and writers of neorealism had had the chance to read it, they would surely have subscribed to it as anticipatory of their artistic intentions.11 Modotti, like her fellow American and European artists, uses the lens to explore and reify her perception of the visible and exploits the photographic lens to search for contrasts and irregularities. Her language is in constant search of unfiltered realities, instantaneous images permeated with vital energy in which the present and memory are realized, blurred and overlapped. In the words of renowned photography critic Rosalind Krauss: "To come to photography after having been intensely and often eventful in Modernism is to feel a strange relief-it is like coming back from beyond the curtain or coming out of a swamp and reaching dry land-because photography seems to propose a direct and transparent relationship with perception, or more precisely with the objects of perception; it does not provoke that sense of deprivation and aggression that one feels when confronted with much of modernist painting and sculpture [...] In short, we turn to photography because Modernism and photography cover almost exactly the same period-which offers a rather illuminating symmetry."12 Tina Modotti falls into that category of artists who succeeded, through the use of the camera obscura, in breaking down the prejudices of a practice considered “masculine” and who, “working often in dangerous situations,” put their own lives at risk. “These were women who helped change customs and bring women out of their situation as ’angels of the hearth, to conquer, at last, albeit laboriously, their place in the world” (Daniela Ambrosio). Tina Modotti’s can thus be defined as an experience of life and art galvanized by a kaleidoscopic and penetrating gaze that embraces the origin of life and the cultural and social construction of the world through a primordial and ritualized gesturality and that regenerates the very concept of artistic making at the time. “Tina Modotti took her photography to international levels thus marking the beginning of the modernist aesthetic in Mexico. She adapted her own vision of modernism to the circumstances of the country in which she worked, a Latin American country still shaken by the tremors, upheavals, and contradictions of a failed revolution. ”13

In conclusion, Tina Modotti occupies a fundamental place in the panorama of international photography. In her work, the static and immobile reality of the shiny camera is transformed into a visual symphony, into a representation that vibrates like a vision heard within an introspective space without a center or a periphery. The result is an alchemical formula, where the mental space of the work becomes an imaginary map for reorganizing and tracing contemporary geographies and forms of humanity. A continuous mutation of tactile and epidermal forms that flow in and out of the photographic plane and generate a captivating and engaging language. From these photographic diaries emerges the Udine artist’s extraordinary character of observing and immortalizing nature, humanity and the conditions of the working classes of the socialist revolution, and which is developed through the narrative of indigenous men, women and children, workers, the homeless, artists and intellectuals, all depicted as the revolutionaries of an era. Above all, however, he lays the groundwork for a new artistic sensibility based on modern photographic technique until then reserved for a purely male practice. The artist thus leaves us with an image on the Dignity of Poverty described with a veracity and spontaneity that gives his images an extraordinary evidence and poetic trace. Her subjects, and especially women, are the heroes of her depictions and visual universe, beautifully and emotionally rendered through the use of light and chiaroscuro. The experiences recounted and passed down through time thus constitute tangible proof that the identity of a place and a people is declined by the language with which it is represented. Streets, people and things, but also paths, looks, sounds and gestures are the fibers of a human fabric that constantly changes. And if the value of art relies on the way it reflects and prolongs notions of culture, education and history it must be able to be directly associated with a linguistic quality, and thus with its durability. Artists like Tina Modotti have the merit of surviving beyond time and history.

1 R. Scorranese, From Edward Weston’s Density of Nature, in Corriere della Sera, La Lettura, May 2016

2 R. Casanova, Costumbrismo Revolucionario, in Alquimia, (3), p.13

3 Lou Benin was an artist who came to Mexico at the invitation of Diego Rivera. The love of theater, the common belief that art is an effective means of social critique united Tina and Bunin, gave rise to a deep understanding between them, evidenced by the power of the moved and joyful participation of those photographs. A.T. Tina Modotti: flashes on Mexico, Ed. Abscondita, 2014, pp.16

4 “Creators of unique photographs, Cunnigham, Kanaga and Lange, contributed in their work to defining terrains of imagination for modern photography. Cunningham’s work also anticipated Weston and gave Modotti a taste for pure images and sharp details.” In Antonio Saborit, Los Objectos Esconden Universos, in Alquimia, (3), p.9

5 Ibid, p.8

6 Similar to Modotti’s rural huts are the images of the Parisian suburbs executed by Atget. For example, the series of photographs made of the dwellings of peddlers and ragpickers at the Porte d’Ivry between 1910 and 1915. Ref. Paris, Eugène Atget, Ed. Taschen, 2008, pp. 196-197.

7 A.T., Tina Modotti: flashes on Mexico, Ed Abscondita, 2014, p.14

8 Ibid, p.16

9 We refer to works such as “Untitled” of 1925 or “Evening Primrose” of 1928, both published in the exhibition catalog Steichen, une épopée photographique, Musée de l’Elisée, Lausanne, Ed. FEP, 2007, pp.174 and 190.

10 Mexican Folkways, 5, 4, Oct.-Dec., Mexico City, 1929

11 Riccardo Toffoletti, Tina Modotti: from form research to social photography, in Tina Modotti, the new rose, art, history, new humanity, exhibition cat., Ed Forum, Udine 2015

12 Rosalind Kraus, Theory and History of Photography, Ed. Bruno Mondadori, 1990, pp. 127

13 A.T., Tina Modotti: flashes on Mexico, Ed Abscondita, 2014, p.17

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.